Type of Object

Harpsichord

- Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766)

- Louis Tocqué (1696–1772)

Though it resided at different times in the homes of two painters—Jean-Marc Nattier and, later, Louis Tocqué—this harpsichord was never really owned by either. Instead, it belonged to their wives and daughters. Originally, it was the possession of Madame Nattier, Marie-Madeleine Delaroche (1698–1742), who acquired it before her marriage to Nattier in 1724 or quite soon thereafter. It had evidently become a treasured possession by the time she died in 1742, at the age of only forty-four, because she bequeathed it to her eldest daughter, Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier (1725–75).1 Still a teenager living in her father’s home when she inherited the instrument, Marie-Catherine-Pauline would take it with her at the age of twenty-one, when in 1747 she became the wife of Tocqué, her father’s former student. The harpsichord even played a role in the marriage proceedings as part of her dowry, a fact that would have a lasting impact on its subsequent journey. According to the legal arrangements laid out in the couple’s , the harpsichord was entailed “en préciput,” meaning that it was kept separate from her husband’s estate when Tocqué died in 1772.2 The harpsichord remained with Madame Tocqué through her short widowhood, and she was ultimately able to bequeath it as she desired. When she died just three years later, it passed to her only daughter, Catherine-Pauline Tocqué, who became the third generation of Nattier-Tocqué women to own this musical instrument.3

When the harpsichord was constructed in the workshop of Nicolas Dumont, a Paris instrument maker, it had been designed with one purpose in mind: to make music.4 Made before 1710, when Dumont died, the Nattier-Tocqué harpsichord was a product of the instrument’s golden age.5 By this point, the harpsichord had developed its familiar form and mechanism: a lidded triangular case containing sets of metal strings (copper for base notes, steel for the higher range), which were plucked (rather than hammered) by jacks with a plectrum (often from a crow feather), each one activated when its corresponding key was pressed by the player’s finger.6 While instrument makers had been perfecting its physical structure, French composers had created a tradition of music specifically attuned to its sonorous qualities—the pièce de clavecin—firmly established in the late seventeenth century by the likes of Jacques Champion de Chambonnière and Jean-Henry d’Anglebert, and reaching its apex in the early eighteenth century with François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau (the latter’s Premier livre de pièces de clavecin appearing in 1706).7 Thus, in its construction the Nattier-Tocqué harpsichord had been optimized as a thing to play a certain kind of music. But whatever its maker’s intention, as is often the case, once the instrument acquired an owner, its function as an object expanded beyond that calling.

It is not that the harpsichord ever stopped being played, but rather that, as a family possession, its life demanded it take on new roles and acquire new meanings. So while its affordances as an object—those physical features that invite use—never changed, the instrument ended up doing things beyond its designed specifications. On its trajectory through the hands of the Nattier-Tocqué women, for instance, the harpsichord was called upon several times to perform more legal services. As property—a thing owned—it acted as an item of inheritance (twice) and as a dowry. Bequeathed and transferred, it circulated between people, tying them together (mothers and daughters; husbands and wives), and leaving a documentary trail through wills and contracts that now allow its life to be traced, at least for a while, in notarial archives. What is more difficult to trace is what it meant on these occasions. For each of these legal acts was also a major event in the life of this family, at which the harpsichord was incongruously present. Through each death and marriage, this object became connected with moments of irreparable loss and change, charged with the emotions of these experiences, from grief and despair to hope and joy. Of course, in between, the harpsichord had more quotidian services to fulfil, being used, as it was intended, for musical entertainments. We might imagine its pièces de clavecin providing the soundtrack to the varied experiences of family life, on dull afternoons or special occasions, for lively gatherings or moments of melancholy. But every now and then, it had more poignant roles to play as a material witness to significant episodes in the lives of the Nattier-Tocqués.

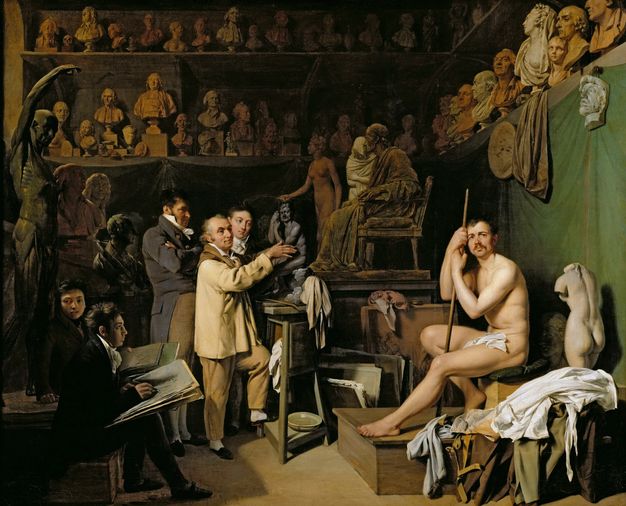

Looking back, those particular events that the harpsichord witnessed—wives and mothers dying, children leaving home—must have felt like the ends of chapters, moments when family life as it had been would forever cease to be so. “Looking back” is certainly what Nattier seems to have done when he painted the harpsichord as part of his Self-Portrait with His Family (fig. 74), a painting whose unusual production involved multiple stages of remembering and revisiting. Nattier began it in 1730, a few years after his marriage to Delaroche and the birth of his children, but then he stopped, putting the work aside unfinished for thirty years, before finally completing it in 1762. By this point, everything had changed. Delaroche was dead. So too was Nattier’s son, Jean-Frédéric, who had drowned tragically while studying in Rome in 1754. Nattier’s three daughters were still alive, but, far from infant children, they were now women in their thirties, all married or about to become so.8 Like everyone else in the scene, the harpsichord had gone too, now residing in the home of Marie-Catherine-Pauline and her husband, Tocqué, as it had done for fifteen years. Yet in his portrait, a nostalgic act of reimagining, Nattier reassembled everything as it once had been.

Nattier’s depiction of the family harpsichord is arresting, not least because eighteenth-century artists did not usually paint their possessions. Despite how it may appear in this book, with its many images of personal objects, the representation of ordinary things was actually quite controlled by the Académie’s hierarchy of genres and restrictions around subject matter. For the most part, everyday objects remained the preserve of still-life or genre painters, like Chardin, who painted his (see fig. 180). Far fewer, for obvious reasons, crept into history paintings—David’s being an exception (see fig. 163). And while certain items did find their ways into portraits, these were usually sartorial accessories, like Vincent’s (see fig. 65), or professional tools, like Houdon’s (see fig. 113). Beyond its mere inclusion, however, what makes Nattier’s harpsichord even more striking is the prominence it is given. Compositionally, the instrument pushes into the foreground, demanding attention as part of the row of figures assembled before Nattier, almost like another member of the family in this lineup of his nearest and dearest. In its treatment too, it is painted more like the figures than the rest of the setting, with more detail and resolution than the chair or table. Moreover, it is given a commanding role, actively orchestrating both the fiction of the image and the reality beyond the object. The harpsichord is the ostensible focus of this gathering, as the erstwhile household enjoys Madame Nattier’s musical entertainments. But it is also the narrator of the family’s history, relating the deaths of the departed members in its two snuffed-out candles and telling the story of the painting itself in the inscription on its cheek: “painting from the studio of Jean-Marc Nattier . . . begun in 1730 and finished in 1762.”9 It might be going too far to describe this image as a portrait of the harpsichord, but the instrument has certainly become the voice of the painting. Imbued with so many memories, this thing seems to have been, for Nattier at least, a material reminder of the past in the present.

It is possible that the harpsichord loomed so large in the Nattier-Tocqué family because it did so literally and figuratively, as significant in sheer size as it was in poignant associations. Nattier’s painting shows a double-manual harpsichord—with two keyboards and two choirs of strings—but it only reveals the tip of the iceberg in terms of the instrument’s dimensions. Some sense of its physical presence can be gleaned from an encounter with one of the only remaining Dumont double-manual harpsichords (fig. 75), now at the Philharmonie de Paris.10 At over two meters long, the instrument would have occupied the better part of all but the largest rooms in the Paris homes inhabited by the Nattier and Tocqué households, whether in the complex of the Templars in the Marais (where Nattier lived in the 1740s), or in Tocqué’s apartments on Rue du Mail, Rue de Cléry, and off Rue Saint-Honoré, or even in the Louvre logement he was granted in 1760.11 Though numerous, most of these moves did not involve great distances, and certainly there would have been larger items to manage (like or chests of drawers) and more fragile items to protect (anything made from porcelain or glass). But the harpsichord’s particular combination of size and delicacy would have made it a logistical challenge on every one of its moves, perhaps never more so than during its relocation after Tocqué’s death. Forced to leave her late husband’s Louvre logement, the widowed Madame Tocqué found first-floor rooms in the convent of Notre-Dame de Bon-Secours, which meant transporting her harpsichord all the way across Paris, right out to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.12

Moving the harpsichord was facilitated by the instrument’s practical detachability from its stand. Though acquired as a complete item, a harpsichord was in fact composed of parts and created by a team of specialized trades. Within the restrictions of Paris’s guild system, the instrument makers, who made and sold harpsichords, were actually only responsible for constructing the case and musical mechanism, while all other elements and decorations were contracted out. A decorative painter was employed to paint the case (most commonly red or, as in this case, a green known as merde d’oie), to adorn the soundboard with floral designs, and sometimes to paint the lid with an Italianate landscape or pastoral scene (as in fig. 75).13 Meanwhile, a menuisier (cabinetmaker) was commissioned to make the legs and frame of the instrument. While the instrument maker determined the harpsichord’s sound, these other agents were responsible for its look, giving it a visual aesthetic that resonated with its musical qualities and harmonized with contemporary domestic interiors.

Design aesthetics were, however, less stable than musical ones. Mechanisms might need repair or tuning (the miniaturist Charles Boit once paid a raccomodeur de clavecins [harpsichord repairer] 8 livres for a service), but the look could be revamped entirely.14 The Nattier-Tocqué family seemingly did this on two occasions, finding yet another practical application for the detachability of the base. If accurately described, the gilded rococo legs in Nattier’s portrait are too modern to be the originals of an instrument made before 1710, suggesting a new stand was commissioned—presumably by Madame Nattier—to keep the object up to date. This vested interest in the fashions of home furnishings may have been inherited by the next generation, for in Madame Tocqué’s inventory of 1775, the harpsichord is described as having “wooden legs painted black and gilded,” indicative of another possible change, perhaps after one of its many relocations.15 Beyond suggesting a certain taste consciousness on the part of its owners (and a ready enough income to satisfy such cosmetic desires), these design modifications also highlight something of the harpsichord’s ambiguous categorization. Unlike smaller musical instruments—say, a guitar (an instrument owned by both Oudry and Vernet)16—the harpsichord’s size and form made it more like a piece of furniture. It was not a thing that could be put away or stored in a case but a thing that had to be accommodated at all times by its setting.

On at least one occasion, however, the harpsichord broke free of its domestic interior, not through a physical relocation, but via a fictional performance. Among the many roles the object played in its long life—musical instrument, item of inheritance, dowry, heirloom, piece of furniture—in 1754 it also became a studio prop for one of Nattier’s most important commissions: his portrait of the king’s daughter, Madame Henriette Playing a Bass Viol (fig. 76).17 By this time, the instrument itself was residing in Tocqué’s home, so Nattier presumably used his unfinished self-portrait as a model, as suggested in the striking similarities not only between the objects (a double manual with a green case, dark cheek, and gilded scalloped legs) but also in their depictions (cut off at the left edge of the canvas, with music on the stand, and a blue curtain overhead). Yet the differences between the family portrait and the royal portrait underscore its different roles in each work: from its dominant foreground position as narrator or quasi member of the family, to an incidental bit part in the mid-ground as a thematically appropriate compositional device. Like David’s in his painting of Brutus, this was a real thing playing a fictional part—the family harpsichord masquerading as the princess’s harpsichord. But unlike the table, designed expressly for that purpose, the harpsichord’s performance was more of a cameo appearance, fifteen minutes of fame before returning to everyday life. ‡

-

It is described as “provenant de la succession de sa mère” in the marriage contract of Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier and Louis Tocqué, 6 February 1747, AN, MC/ET/LIX/238. The contract is transcribed in Philippe Renard, Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766) (Saint-Rémy-en-l’Eau: Monelle Hayot, 1999), 194. ↩︎

-

Marriage contract, Louis Tocqué and Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier, 6 February 1747, AN, MC/ET/LIX/238. ↩︎

-

The harpsichord is not mentioned separately in Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier’s will, but Catherine-Pauline Tocqué was designated as her mother’s principal heir, inheriting everything apart from a small number of specific items bequeathed to family members and servants. Will, Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier (Madame Tocqué), 27 March 1775, AN, MC/ET/CXIII/477. See also Renard, Jean-Marc Nattier, 205. ↩︎

-

It is described as a Dumont harpsicord in the estate inventory of Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier (Madame Tocqué), 10 April 1775, AN, MC/ET/CXIII/477. ↩︎

-

Nicolas Dumont (1673–ca. 1710) was a Parisian harpsichord maker, received into the Guild of Instrument Makers in 1675. Donald H. Boalch, Makers of the Harpsichord and Clavichord, 1440–1840, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995), 52, 305–6. On the form of the harpsichord, see Edward L. Kottick, A History of the Harpsichord (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003). Thanks to Julie Anne Sadie Goode and Jenny Nex for assistance with research on eighteenth-century French harpsichords. ↩︎

-

On the materials used in eighteenth-century French harpsichords, see “Clavecin,” Encyclopédie, http://encyclopedie.uchicago.edu/), 3:509. ↩︎

-

On the early evolution of harpsichord music, see Carol Henry Bates, “French Harpsichord Music in the First Decade of the Eighteenth Century,” Early Music 18, no. 2 (May 1989): 184–96. ↩︎

-

The youngest, Madeleine-Sophie, would marry the painter Charles-Michelange Challe the following year. For a more extensive analysis of this family portrait, see Hannah Williams, Académie Royale: A History in Portraits (New York: Routledge, 2015), 189–92, 198–99. ↩︎

-

The full inscription is: “Tableau de lattelier de M. / Jean-Marc Nattier trésorier / de Lacademie Royale de Peinture / et de Sculpture / commencé en 1730. et fini / par Le dit S. en 1762.” ↩︎

-

Physical comparisons are difficult because the Philharmonie de Paris instrument was modified by Pascal-Joseph Taskin in 1789. ↩︎

-

For Nattier’s and Tocque’s addresses during their careers, see Hannah Williams and Chris Sparks, Artists in Paris: Mapping the 18th-Century Art World, www.artistsinparis.org. ↩︎

-

Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier (Madame Tocqué), “Inventaire après décès,”10 April 1775, AN, MC/ET/CXIII/477. See also Renard, Jean-Marc Nattier, 148. ↩︎

-

On the decoration of harpsichords, see Sheridan Germann, “Monsieur Doublet and His Confrères: The Harpsichord Decorators of Paris,” Early Music 8, no. 4 (1980): 435–53; and Kottick, A History of the Harpsichord, 263–64. ↩︎

-

An opposition by Jean Desnoue, raccommodeur de clavecins, was made in the Scellé of Charles Boit on 6 February 1727. AN, Y/15767. ↩︎

-

Marie-Catherine-Pauline Nattier (Madame Tocqué), “Inventaire après décès,” 10 April 1775, AN, MC/ET/CXIII/477. ↩︎

-

Louis Gougenot, “Vie de M. Oudry,” in L. Dussieux et al., eds., Mémoires inédits, 2:379; and Léon Lagrange, Joseph Vernet et la peinture au XVIIIe siècle, avec le texte des livres de raison et un grand nombre de documents inédits (Paris: Didier, 1864), 392. ↩︎

-

The harpsichord would appear in several versions and studio copies of this important commission. ↩︎