In preparation for a multivenue loan and the rigors of transatlantic travel, Titian’s Rape of Europa underwent a structural treatment in 2018. Remarkably, the painting retains what appears to be a late-eighteenth-century glue-paste lining. While the painted surface was stable, it was observed that sections of the lining canvas had detached along the edges of the cropped original canvas support and that the painting was also extremely loose on its strainer. Although the notion of relining was considered, it was decided to preserve the old glue-paste lining. The strainer, dating from the time of the lining procedure, was in poor structural condition, exhibiting severe bowing of the cross members, extremely weak corner joints, and woodworm damage. As these condition problems precluded the original strainer’s reuse, a new modified stretcher system, incorporating lightweight, rigid panel inserts and a loose-lining fabric, was employed to support the painting.

52. The Structural Treatment of Titian’s Rape of Europa: Extending the Life of a Two-Hundred-Year-Old Glue-Paste Lining

- Courtney Books, Paintings Conservator, Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri

- Corrine Long, Associate Paintings Conservator, Gianfranco Pocobene Studio

- Gianfranco Pocobene, Chief Paintings and Research Conservator, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Introduction

The Rape of Europa (1560–62) is one of six canvases from Titian’s seminal Poesie paintings, commissioned by Philip II of Spain.1 Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the mythological painting depicts the moment of Europa’s abduction by Jupiter, who took the form of a bull and carried her off to Crete. Where and how Philip II displayed the Poesie series in Madrid remains unclear, but by 1707 Europa was in the collection of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, in Paris. In 1793, Europa was transported to England, where it remained in the collection of the Earl of Darnley until Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased it in 1896, on the advice of Bernard Berenson. For more than 120 years, it has been on permanent display in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s Titian Room. In 2020–21, the Poesie paintings were reunited for the first time in over four hundred years for the international exhibition Titian: Love, Desire, Death, with exhibitions at the National Gallery, London; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

When the exhibition was first proposed, concerns about the condition of the Rape of Europa were raised, as it had never previously been loaned. An examination by Andrea Rothe in 1989 indicated that while the painting was well preserved and stable, with regard to the lining, “under no circumstance should the painting travel in its present state.”2 At the curator’s request, a preliminary examination of the canvas was conducted in 2017 to consider the viability of loaning the picture. While several condition issues were discovered, it was determined that with appropriate structural intervention, the painting could be stabilized and reinforced for travel. In 2018, the museum’s commitment to participate in the historic exhibition compelled a thorough assessment of Europa’s structural and aesthetic condition, and it was concluded that the painting required treatment. Three distinct but interrelated phases of work composed the project:

-

Comprehensive technical and analytical research to determine Titian’s techniques and materials, and to ensure the appropriate treatment procedures (see the appendix for a description of the analysis)

-

A minimally invasive structural treatment to support the canvas for travel to Europe and ensure long-term preservation

-

Cleaning and aesthetic restoration to remove discolored coatings and to realize selective retouching of abraded paint layers

This essay focuses on the structural treatment of the Rape of Europa in preparation for the exhibition. Once the physical concerns were identified, a structural support system, which sought to impart no change to Titian’s canvas, was devised.

Material Composition

The large-scale (71 3/4 × 80 1/2 inch [182.2 cm × 204.5 cm]) painting is executed in oil paint on linen canvas. The original support is a sixteenth-century herringbone canvas constructed from two pieces of fabric sewn together with a slightly curved, vertical seam 95 cm from the left edge. The original canvas is lined onto a secondary support with a protein-based adhesive. The auxiliary canvas comprises two pieces of herringbone-weave linen sewn together with a vertical seam 89.5 cm from the left edge; it was likely manufactured before the mid-nineteenth century, when fabrics were fabricated on a handloom and typically did not exceed a meter in width. It is therefore presumed that the lining likely occurred in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Hot, heavy irons would have been used to bond the canvases, which accentuated the seam and the weave.

The painting was stretched over a lightweight, six-member softwood strainer with metal tacks along the tacking margins. Two cross members reinforced the strainer and hand-forged nails secured the corner lap joints. The nonoriginal strainer is likely contemporary with the glue-lining procedure.

The preparatory layer consists of an exceptionally thin gesso (calcium sulfate) ground. Titian then applied oil-bound pigments in mostly thin, energetic brushstrokes and used varied techniques of dry scumbles and binder-rich glazes. Surface coatings were a thin layer of aged, natural resin varnish intermeshed with proteinaceous lining-adhesive residues.

Condition Concerns

The condition of the painting’s support system generated considerable concern. Structurally, the weakened strainer was inadequate: the cross members had developed a prominent outward bow on the reverse, the strainer members were brittle from woodworm damage, and the lap joints were weak and loose. The adhesion between the lining fabric and the original canvas was also questionable. There were instances of adhesion failure between the original and lining canvases, which resulted in small separations along the edges. Furthermore, tearing of the lining at the tacking sites contributed to looseness of the canvas support. The assortment and severity of condition issues prompted an initial consideration of relining. Despite some occurrences of delamination at the lining’s edges, however, gentle probing between the canvases with a microspatula proved the bond strength of the adhesive to be fully adequate. Further investigation with raking light and sounding with fingernails confirmed adhesion away from the edges.

Structural Treatment and Methodology

Several objectives guided the structural treatment of Titian’s Europa. The overarching principle was to use materials congruent with the historical materials present, both original and belonging to previous interventions. Treatments deemed more aggressive, such as subjecting the canvas to lining removal and potential stress to paint layers, were to be avoided. Furthermore, the treatment needed to impart adequate resistance to vibrational/mechanical stress (i.e., rigid support), while simultaneously avoiding immobilization of the paint and canvas structure.

The structural treatment was executed in two stages: the first involved stabilization of the original canvas and lining canvas and reinforcement of the lining support; the second comprised the restretching of the painting and implementation of a blind-panel stretcher and loose-lining fabric support.

The first stage included re-adhering the detached areas of lining fabric, removing the canvas from the unstable strainer, and adjusting the seam allowance of the loose-lining so that it would not impart an impression onto the painted surface. The second stage involved constructing a blind-panel stretcher and installing the loose-lining. The custom blind-panel design would replace the structurally weak strainer and add stability and resistance to mechanical stresses by providing additional support (fig. 52.1). Complete restriction of the painted canvas was avoided by using the loose-lining technique to provide a gentle nap bond. Preventive measures were also taken by reducing excessive tensioning during restretching to ensure the picture plane remained unaltered. Following structural treatment, comprehensive technical analyses were executed, and continued conservation work, such as varnish removal, retouching, and revarnishing, was performed.

Structural Treatment

Part 1: Treatment of the Lining Support

The painting, laid facedown on a smooth table surface, was separated from the strainer by removing the metal nails. The bottom turnover edge had become a dirt pocket that was heavily caked with soil, insect casings, straw, and debris. The reverse was vacuumed using a HEPA filter and soft brushes, followed by overall surface cleaning with latex sponges.

To prevent distortions from imprinting to the pictorial face, textural aberrations in the historical lining fabric were reduced. This included minor slubs and embedded debris, as well as leveling of the 1/2-inch-wide seam allowance of the lining canvas using a scalpel. Minor gaps between the two lining canvases were reinforced to prevent separation of the seam. Linen fibers, flocked for compacting power, were saturated with an adhesive paste of rabbit-skin glue, wheat-starch paste, and Klucel G (6:4:1) and applied along the entire seam. The flock reinforcements were weighted under blotters for ten minutes and then ironed with mild heat and pressure until the seam was smooth and dry.

Strips of Belgian linen were prepared for strip-lining with Beva film (fig. 52.2). To stiffen and prevent distortion of the turnover edge, 1 1/2-inch strips of polyester sailcloth were adhered to the inner side of the strip-lining with Beva 371 film aligned with the tacking margin.

With the painting facedown, the 4-inch buckle at the upper left corner and a few small areas along the border juncture of original canvas and lining canvas were re-adhered. The same glue-paste-Klucel adhesive mixture used to reinforce the seam allowance was fed into the delamination pockets (humidified with atomized water) with brush and microspatula, then set down with gentle heat applied with a tacking iron through Remay cloth and blotters and weighted until dry.

Part 2: Blind-Panel Stretcher + Loose-Lining Hybrid Treatment

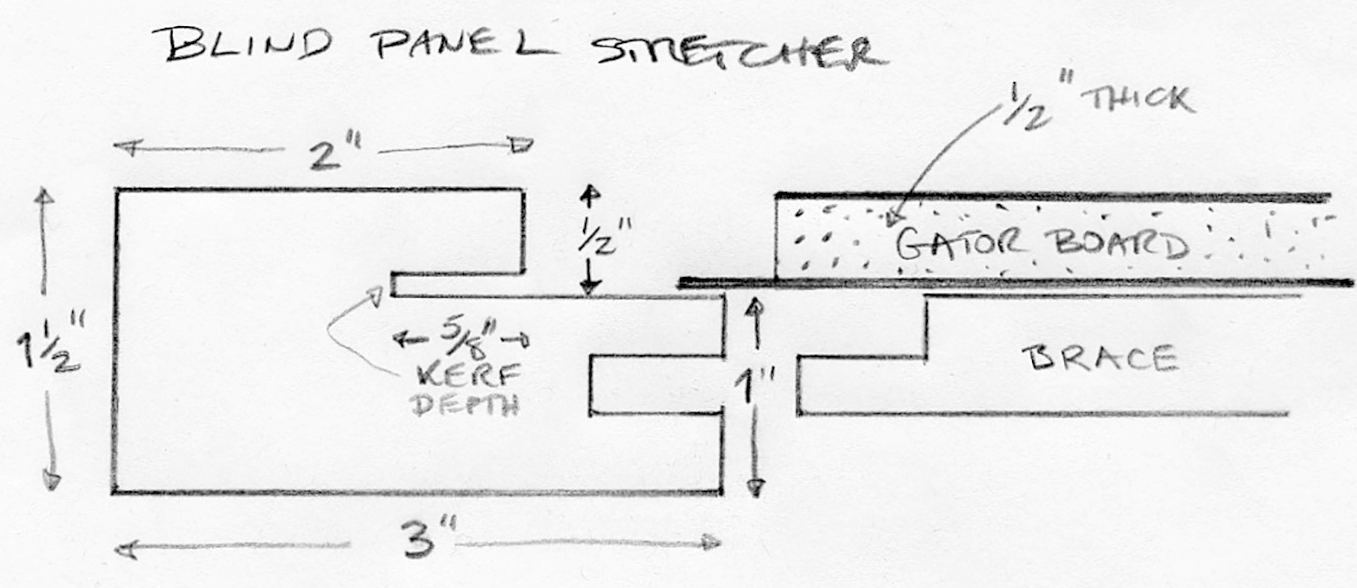

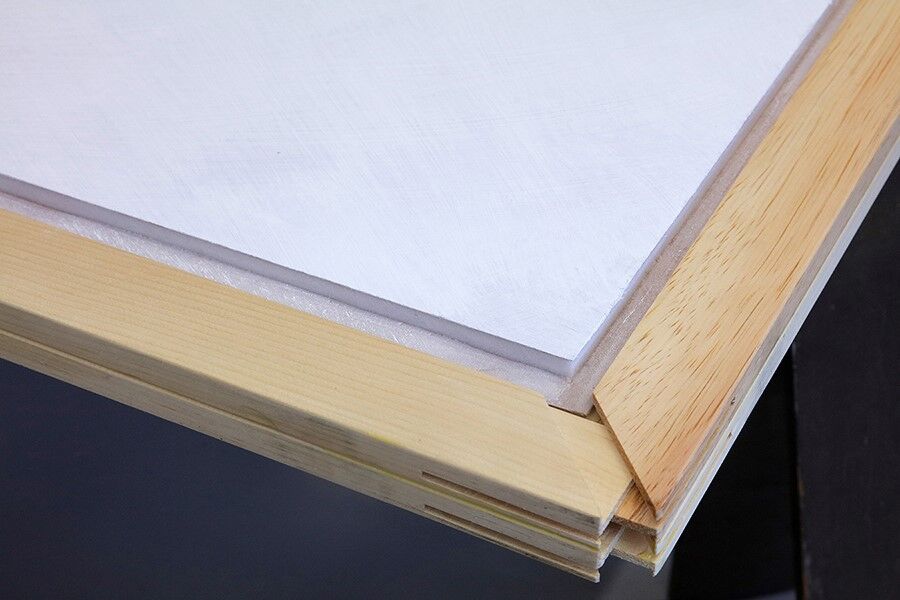

The new stretcher, reinforced with four cross braces (two horizontal, two vertical), was custom fabricated by Upper Canada Stretchers to receive interlocking blind-panel inserts to create a flush, rigid surface for the painting’s pictorial plane (fig. 52.3). Along the inner surface of each 3-inch stretcher bar, a 1-inch-wide × 1/2-inch-deep recess was cut into the wood, along with a 5/8-inch-deep kerf that followed flush along this recess (fig. 52.4). This would allow for the panel inserts to interlock tightly within the stretcher bar system, ensuring a level, immobile support.

The blind-panel inserts, constructed from three sections of Gator Board, were cut to fit in the stretcher recess and prepared with acrylic gesso medium to prevent migration of any degradation by-products. Then 1/2 × 1/2 inch sections of laminate surface and foam were cut away from the outer borders of each panel, leaving the bottom skin of the board protruding to lock into the kerf cut of the stretcher bar (see fig. 52.4). After the insert panels were locked into place, each panel was secured to the cross members with wood screws, and each screw location was covered with a thin patch of polyester fabric adhered with Beva film.

Belgian linen was stretched over the blind-panel stretcher and attached with staples secured along the turnover edges followed by securing the strip-lining edges with pushpins to align the painting (see fig. 52.3). The painting was stretched over the loose-lining and attached with staples secured to the strip-lining fabric. This was accomplished with the painting faceup, supported by sawhorses, and executed by two people working in tandem (fig. 52.5). The rigid support prevented sagging of the original canvas because it was fully supported and in plane while it was being stretched in the horizontal position. Therefore, only minimal tensioning of the painting was needed, as the strip-lined edges were attached to the stretcher. In addition, the loose-lining provided some cushioned support between the old lining canvas and the rigid blind-panel stretcher support. The rigid panel inserts also serve as a kind of inherent protection system typically provided by backing boards.

Reflections

The decision to conserve the auxiliary and fabric supports of Titian’s Europa was not a capricious one: the ethics of less or no treatment versus a thorough structural treatment were weighed and evaluated. At the time of treatment, the framing and display conditions for the exhibition were unknown. In London, the painting was rehoused in a well-designed, period-reproduction frame crafted at the National Gallery, which included nonreflective glazing. In hindsight, would the treatment applied still be deemed necessary? Ultimately, the stress of travel, despite the most secure packing or framing conditions and materials, would have placed the painting and historical, degraded wood strainer at risk. The implementation of a new stretcher and rigid support system fully prepared the structure for safe travel and future security at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Fortuitously, the stabilizing intervention of the support greatly facilitated safe and more accurate technical analysis, especially macro X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (MA-XRF) scanning research that clarified the approach to cleaning and visual reintegration of the picture preceding its reunion with the rest of the Poesie paintings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Kalan and Christina Nielsen at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum; Ian Hodkinson, Professor Emeritus at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario; Lorraine Biggrig, Studio TKM Associates, Ltd.; and Upper Canada Stretchers, Owen Sound, Ontario.

Appendix: Analytical Techniques Used

High-resolution imaging was carried out in visible, UV, and infrared wavelengths. X-radiographs taken in 1980 were digitized and stitched together, allowing for a detailed examination of the painting’s structure. MA-XRF cross-section analysis and scanning electron microscopy–energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) were used to determine the structure and elemental composition of pigments. Collaborators on the analytical work include Courtney Books, Jessica Chloros, Richard Newman, Gianfranco Pocobene, and Aaron Shugar.

Notes

-

The other paintings in the series are Danae (1553–54), Wellington Collection, Apsley House, London; Venus and Adonis (1553–54), Museo Nacional del Prado; Diana and Actaeon (1559) and Diana and Callisto (1559), National Gallery, London, and National Galleries of Scotland; and Perseus and Andromeda (1554–56), Wallace Collection, London. ↩︎

-

Andrea Rothe, examination notes, December 9, 1989, Paintings Conservation Treatment Files, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. ↩︎