Paintings conservators at the Smithsonian American Art Museum survey conservation records to gather the historical recipes, treatment protocols, and materials used over the past fifty years to build a reference database connected to specific works in the collection. From this information, the authors show how the database is being used to re-create both historical wax-resin recipes and application techniques through lining mock-ups. This material reference set is being used for analytical and physical testing to learn more about the materials used and how they degrade, and what influences mechanical as well as environmental conditions have on both the lining recipes and reconstructions as they age.

17. Chronicles in Wax-Resin Lining: A Historic Look at Lining Practices and Their Effectual Legacy on Paintings in the Smithsonian American Art Museum Collection

- Amber Kerr, Head of Conservation and Senior Paintings Conservator, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

- Gwen Manthey, Paintings Conservator, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

- Keara Teeter, Postgraduate Fellow, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

- Kristin DeGhetaldi, Paintings Conservator, Independent Researcher

- Brian Baade, Paintings Conservator and Associate Professor, University of Delaware

- W. Christian Petersen, Volunteer Conservation Scientist and Affiliated Associate Professor, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Winterthur, Delaware

- Catherine Matsen, Scientist and Affiliated Associate Professor, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Winterthur, Delaware

Introduction

The Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC, together with its branch museum, the Renwick Gallery, stewards a national collection containing thousands of paintings that span more than three centuries of American art. Established in 1829, the collection at SAAM moved to its current location in the Old Patent Office Building in 1968. This was just two years after paintings conservator Charles Olin formed the first conservation lab for the collection. The paintings in the collection have been cared for by four generations of conservators over the past fifty years.

The conservation records reflect evolving approaches to the methodology and protocols used in the structural treatment of paintings, as they encapsulate the training, experience, and philosophical approaches to treatments brought by each paintings conservator. Research into these past treatments continues in order to gain a greater understanding of the materials used as well as the application methods and overall intent of the treatments. The initial phase of research focused on wax-resin linings and their effectiveness and longevity as a treatment option for paintings in the collection, and, through the use of instrumental analysis, compared specific recipes recorded in treatments with samples from the paintings exhibiting lining deterioration.

The impetus for the focus on wax-resin linings began several years ago, when a significant number of those lining treatments completed in the mid- to late twentieth century were beginning to fail or showed early signs of failure. Modes of failure included but were not limited to pocketed delamination of the lining substrate, returned cupping and flaking within the paint and ground layers, and raised craquelure in the painted surface. Of note was the delamination of linings related to works that were on prolonged view in the galleries or had traveled on loan. The latter was of particular concern, as these paintings were considered the best for loan based on the very fact that they were wax-resin lined, and therefore considered stable and nearly impervious to environmental fluctuations or mechanical stresses.

Collection Survey and Lining Reconstructions

A survey of the Lunder Conservation Center treatment records was initiated to identify lined paintings in the museum collection. As of April 2019, this survey yielded a preliminary data set of 958 linings carried out at the museum from the 1950s to present. The data set was then filtered to exclude paintings mounted to solid supports, adhesives irrelevant to this study (glue paste and synthetic), and wax-resin adhesives where the materials were unidentified. The final data set yielded fifty oil-on-canvas paintings lined between 1950 and 1993. The paintings were by thirty-seven different artists and on a variety of fabric supports (linen, cotton, and burlap). All were wax-resin lined but nearly a dozen different recipes had been used. The linings were added to address a variety of condition issues, including tears, generalized flaking, or as a preventive measure (no condition issues noted).

Six recipes were frequently used in the twentieth-century lining treatments and were found in forty-three of the fifty surveyed paintings (table 17.1). These six recipes were then selected for comparative and categorical reasoning in order to answer the following queries:

| Case study painting | 2019 re-created recipe | Collection survey |

|---|---|---|

|

Sun Setting, Denmark |

SAAM 1 (Keck recipe):

|

SAAM 1 represents:

|

|

Oak Trees |

SAAM 2:

|

SAAM 2 represents:

|

|

Cagnes-sur-Mer |

SAAM 3:

|

SAAM 3 represents:

|

|

The Lesson |

SAAM 4:

|

SAAM 4 represents:

|

|

Plenty |

SAAM 5:

|

SAAM 5 represents:

|

|

The Windmill |

SAAM 6:

|

SAAM 6 represents:

|

Note: Each case study painting represents a different historical lining recipe (SAAM 1–6). The third column compares each case study to surveyed lining adhesives, prevalence of its use on other works by the same artist, and prevalence of its use with the same secondary support. The breakdown of secondary supports is as follows: linen (10/50 linings), fiberglass (18/50 linings), combination of linen and fiberglass (3/50 linings), and unidentified textiles (19/50 linings). Supports for Cagnes-sur-Mer, The Lesson, and The Windmill were unidentified in April 2019; visual examination later revealed that all three supports were linen.

Table: Amber Kerr, Gwen Manthey, Keara Teeter, Kristin DeGhetaldi, Brian Baade, W. Christian Petersen, and Catherine Matsen

-

Had other institutions also observed wax-resin lining failure? This would be determined by examining a recipe frequently used by conservators working in a range of institutions: SAAM 1.

-

Was the type of resin, type of wax, or their relative proportions a source of failure? Two sets of recipes would be compared to evaluate this question: SAAM 2 and 3 versus SAAM 4 and 5.

-

Did the use, substitution, or absence of a particular resin or an organic wax contribute to failure? This would be determined using SAAM 6.

The six recipes were each reconstructed to better understand how the lining adhesives were aging and for comparison against aged samples from known examples of use (the case studies listed in table 17.1).

One case study was selected to represent each lining recipe, and samples of excess wax-resin adhesive were taken from each. The case studies represent a variety of painting techniques, as well as previous condition issues. In the case of both William H. Johnson paintings, they had been exposed to extremely poor environmental and storage conditions prior to acquisition. In the case of The Lesson by Hugo Ballin and Plenty by Kenyon Cox, those works entered the collection almost immediately after their completion by the artists. In addition, the case studies reflected differences in lining supports, and lining recipes that are often repeated on other works by the same artist (particularly in the works by Johnson and Bannister).

Ingredients used in the recipes were sourced from various vendors, inventory at the Lunder Conservation Center, and donations coordinated with institutions and private practice conservation studios.

The six reconstructed recipes were used in mock-up linings of thirty-six test paintings. The test paintings consisted of commercial acrylic-primed cotton, acrylic-primed linen, and oil-primed linen canvases mounted to 20 × 25.5 cm (8 × 10 inch) wooden stretchers (twelve each). The authors marked each canvas with graphite (underdrawing) and applied Weber Permalba zinc and titanium white, Gamblin yellow ochre, or Old Holland red ochre oil paints; four of each canvas type were painted out with each pigment type. These pigments were chosen based on the practical experience of the authors and conventional wisdom that they dry quickly.

Viscosity was divided into three categories: thin, moderate, and thick oil paint. The thin layer was diluted in mineral spirits and applied lightly using 2.5 cm (1 inch) nylon flat brushes so that the graphite underdrawing remained visible. The moderate layer was conservatively applied from the tube by brush (brushed gently to an even layer with little brush marking), obscuring the underdrawing. The thick layer was liberally applied from the tube by brush and palette knife to build up impasto. All mock-ups were aged for four days at room temperature and then desiccated for fifteen days in a Lab-Line L-C oven set between 32°C and 40°C (90°F and 105°F). Once the oil paint was completely dry, each mock-up was photographed before treatment, removed from its stretcher, and lined to 38 × 43 cm (15 × 17 inch) fabric supports, distributed evenly between linen and fiberglass.

Ingredients for each reconstructed lining recipe (see table 17.1) were measured by weight and bundled in cheesecloth in packages weighing 1 kg each. The six cheesecloth packages were added to 24 × 24 × 9.5 cm (9.5 × 9.5 × 3.75 inch) Gotham Steel nonstick fry pans and heated on an iSiLER CHK-S1809NE portable induction cooktop to 126°C–238°C (260°F–460°F). Large impurities were separated out as the molten wax-resin components permeated through the cheesecloth. Once filtration was complete, cooktop temperatures were reduced to 82°C (180°F). The molten mixture was transferred to the mock-ups (canvas reverse) and secondary support fabrics using polyester paint rollers. The cotton/linen/fiberglass edges were masked in 10 cm (4 inch) wide strips with silicone-release Mylar to prevent excess buildup of lining adhesive.

Once coated with the wax-resin mixture, each mock-up painting was centered on its secondary support, placed on the vacuum hot table, and sealed inside a silicone-release Mylar envelope. The vacuum suction pressure was set to 1 Hg (0.49 psi) and the heat to 74°C (165°F). Emergency thermal blankets were used to cover the Mylar envelope to encourage even heat distribution. After fifteen to twenty minutes of monitoring, the heat was turned off and the emergency thermal blankets removed. Then the mock-ups were hand-pressed in a Union Jack pattern through the Mylar envelope to push out excess wax-resin adhesive. Brayers were used over the thin and moderate paint layers, and cloth diapers were used over the thick impasto. The lining procedures followed for the research project reflect treatment reports as well as oral history interviews with former staff conservators.

Sample Prep and Analysis

Scraped lining adhesive samples were collected from eighteen of the fifty surveyed paintings (including all six case study paintings), raw wax and resin ingredients, and each lining reconstruction adhesive. Technical examination was carried out in May and June 2019 at the Winterthur Museum’s Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory (SRAL).

For the first stage of analysis, samples were prepared for Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The samples were flattened onto diamond cells to be analyzed with a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer. The samples were spread out as a translucent film using a stainless steel microroller, and the diamond cell placed on the platform of a Nicolet Continuμm Infrared Microscope. One or two target sites were selected on the diamond cell, and data were collected in transmission mode. Spectral resolution was set at 4 c-1 for 128 scans (each scan ranged from 4000 c-1 to 650 c-1). The resulting spectra were interpreted using OMNIC Series Software (version 8.0) and compared to the Infrared and Raman Users Group (IRUG) spectral database.

During the second stage of analysis, samples were transferred to Thermo Fisher Scientific autosampler vials to be analyzed with an Agilent Technologies 7820 gas chromatograph and Agilent 5975 Mass Selective Detector (GC/MSD). The autosampler vials were treated with 1 part Grace Alltech Meth-Prep II reagent in 2 parts benzene (≤100 µL) and warmed in a Lab-Line Multi-Blok heater at 60°C for an hour. The derivatized sample was pipetted into a vial insert and cooled to room temperature. From each vial, 1 μL of the sample was injected into the HP-5ms GC column (5% phenyl methyl siloxane; flow rate of 1.5 mL/minute; film thickness of 30 μm × 250 μm × 0.25 μm). After injection of the sample, Agilent G1701EA GC/MSD ChemStation software was used with Winterthur RTLMPREP method set to the following conditions:

-

Inlet temperature set at 320°C in “splitless mode” with a nine-minute solvent delay

-

GC oven temperature set at 55°C for two minutes and then ramped up 10°C per minute to 325°C, followed by a ten-minute isothermal period

-

Transfer line temperature to the MSD in scan mode at 280°C, the source at 230°C, and the MS quad at 150°C.

Chromatograms and mass spectra were interpreted using Agilent MSD Enhanced ChemStation data analysis software with NIST MS Search v.2.0 database.

During the final stage of analysis, samples were derivatized with 3 μL tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH; 25 wt.% in methanol) and placed in a stainless steel Eco-Cup (50 μL). The Eco-Cup was inserted into a Frontier Lab Multi-Shot EGA/PY-3030D for pyrolysis with a Hewlett Packard 6890 gas chromatograph and HP 5973 mass selective detector (Py-GC/MSD). The Eco-Cup was fitted with an Eco-Stick and inserted into the pyrolysis interface, where the sample was purged with helium using a single-shot method at 600°C for twelve seconds. Separation was achieved with an Agilent J&W DB-5ms 19091S-433 capillary column (30 μm × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) with helium carrier gas set to 1.2 mL/minute. The split injector was set to 280°C with a split ratio of 30:1 and no solvent delay (9.26 psi). The GC oven temperature program began at 43°C for two minutes, ramped up by 10°C per minute to 325°C, and then set a five-minute isothermal period (total run time = 34.7 minutes). The MSD transfer line was set at 320°C, the source at 230°C, and the MSD quad at 150°C. The mass spectrometer was scanned from 33 to 600 amu at a rate of 2.59 scans per second. Total run time was 29.4 minutes.

Results and Discussion

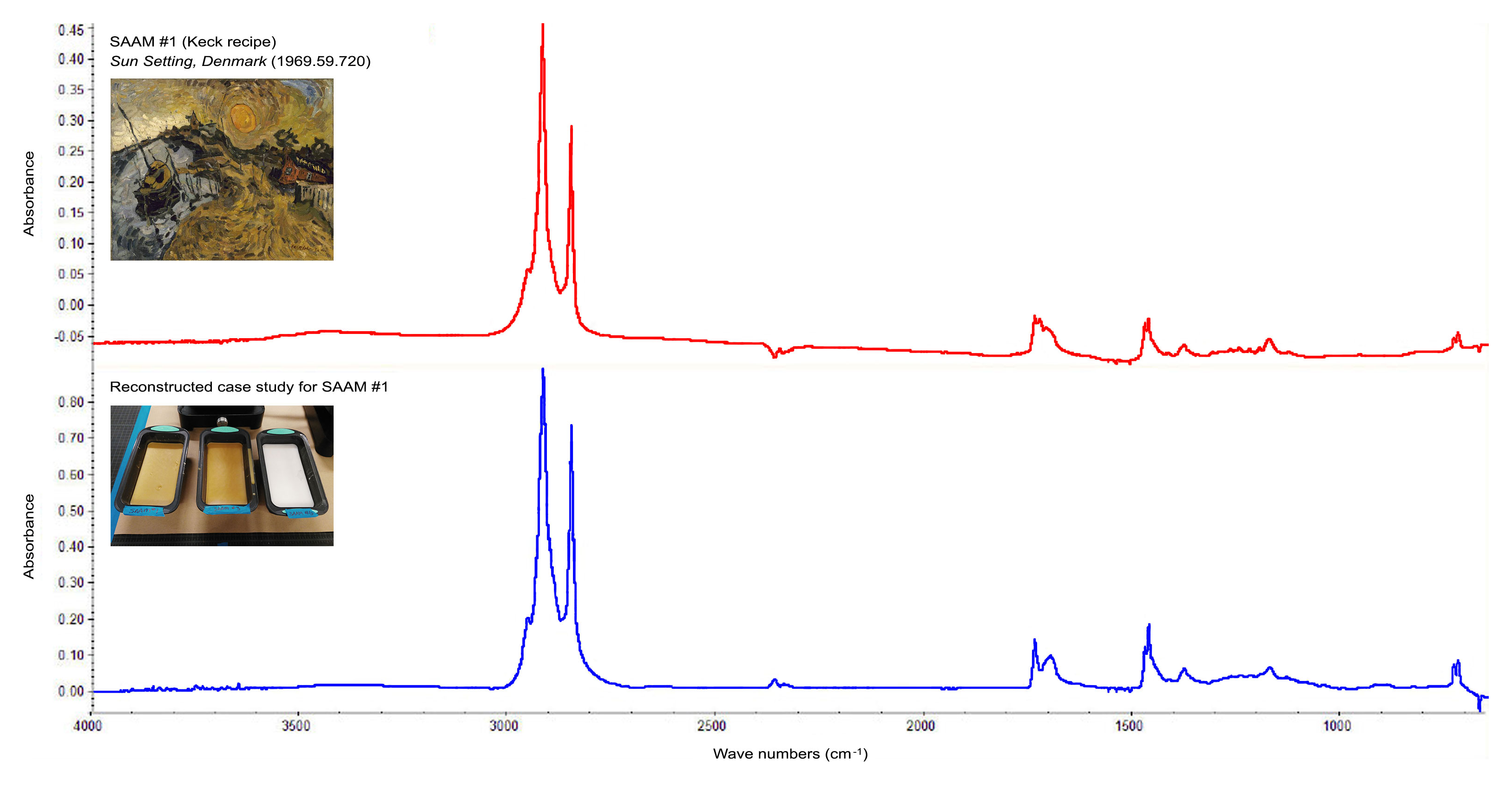

Each case study painting, SAAM reconstructed recipe, and raw material sample was analyzed using FTIR and GC/MSD. The goal of FTIR analysis was to compare the transmission band pattern of the historical linings to the reconstructed recipes (fig. 17.1). This comparison helped measure the efficacy of replicating SAAM’s historical lining recipes. FTIR was not used to confirm the presence or absence of the raw material components, as that step would require a more discerning analytical technique.

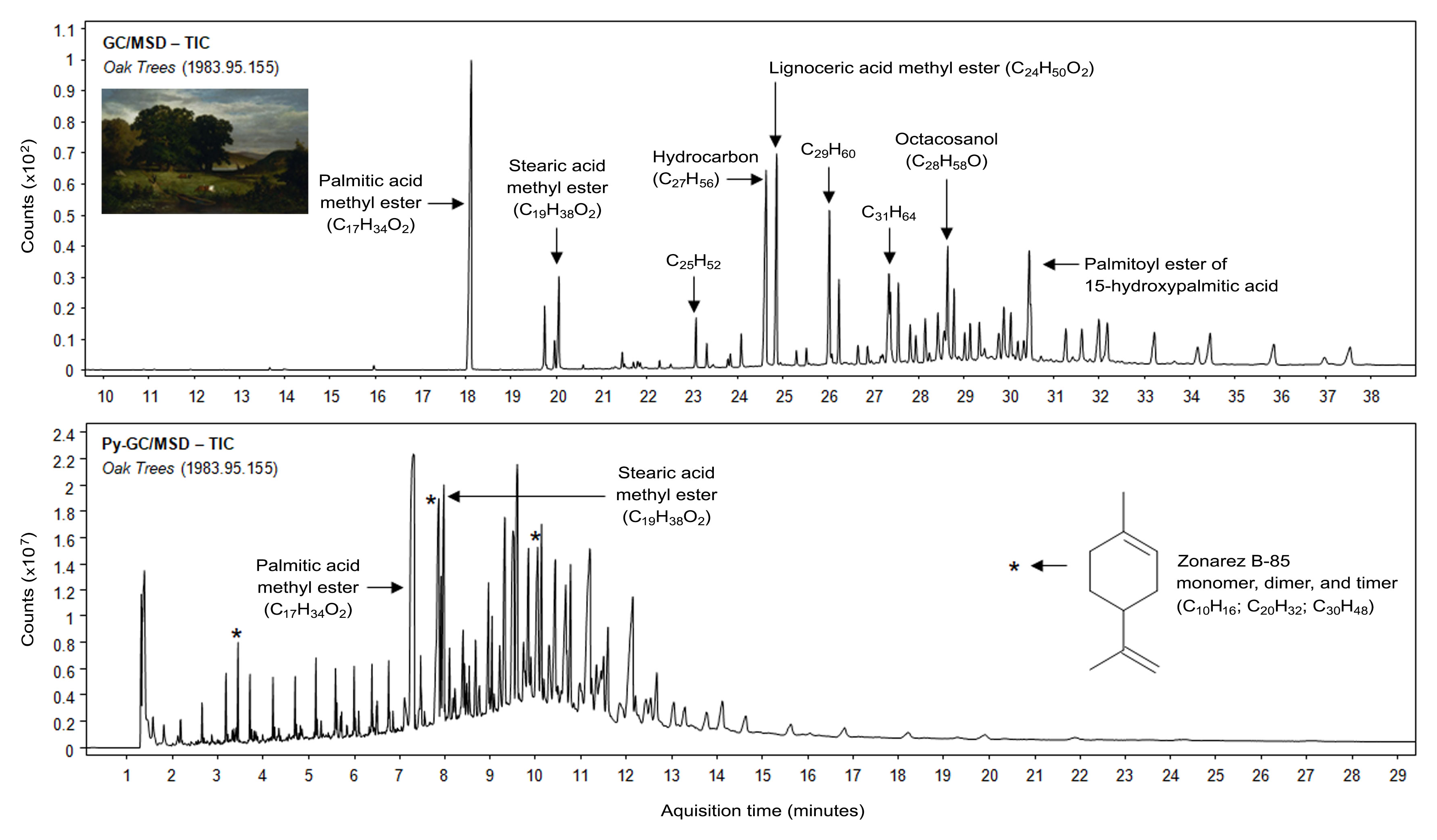

GC/MSD provided supplemental information about the material composition of each adhesive mixture. Odd-numbered chain length hydrocarbons and certain fatty acids (including palmitic, stearic, and lignoceric acids) identified beeswax in the sample. Odd- and even-numbered hydrocarbons with a reduced fatty acid content indicated the presence of microcrystalline wax in the unadulterated samples such as The Windmill and SAAM 6. However, the presence of microcrystalline wax was more difficult to detect in samples containing a mixture of ingredients. Multiwax W-445 was present in all twelve samples; however, it was detected in only three case study paintings (The Lesson, Plenty, and The Windmill) and four re-created recipes (SAAM 2, and 4–6). In this data subset, beeswax was absent from six of the seven samples.

Some natural resins were successfully identified with GC/MSD: 5-dammarenolic acid methyl ester signaled the presence of dammar, dehydroabietic acid and 7-oxo-dehydroabietic acid1 signaled colophony, and α- or β-amyrin signaled gum elemi. The two proprietary resins Zonarez B-85 and Piccolyte S-85 were not conclusively detected with GC/MSD (fig. 17.2, table 17.2). This could be the result of shortcomings in the sample derivatization process or sensitivity of the GC/MSD instrument. Other research publications have also cited discrepancies in identifying resins due to oxidation, depolymerization, or cross-linking of the material as it ages (Bleton, Jean, and Alain Tchapla. 2009. “SPME/GC-MS in the Characterisation of Terpenic Resins.” In Organic Mass Spectrometry in Art and Archaeology, edited by Maria Perla Colombini and Francesca Modugno, 261–302. Chichester: Wiley.; Lluveras, Anna, Ilaria Bonaduce, Alessia Andreotti, and Maria Perla Colombini. 2010. “GC/MS Analytical Procedure for the Characterization of Glycerolipids, Natural Waxes, Terpenoid Resins, Proteinaceous and Polysaccharide Materials in the Same Paint Microsample Avoiding Interferences from Inorganic Media.” Analytical Chemistry 82, no. 1: 376–86.; Martín-Ramos, Pablo, Ignacio Alonso Fernández-Coppel, Norlan Miguel Ruíz-Potosme, and Jesús Martín-Gil. 2018. “Potential of ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for the Classification of Natural Resins.” Biology, Medicine, Engineering, and Science (BEMS) Reports 4, no. 1: 3–6.; Modugno, Francesca, and Erika Ribechini. 2009. “GC/MS in the Characterisation of Resinous Materials.” In Organic Mass Spectrometry in Art and Archaeology, edited by Maria Perla Colombini and Francesca Modugno, 215–35. Chichester: Wiley.).

| Ingredient | Compounds in waxes/resins detected with GC/MSD | Retention time (min.) | Ions (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unbleached beeswax |

Odd-numbered hydrocarbons (peak at

C27H56) Fatty acids (most peak at C24H48O2) |

24–25 (peak) | 71, 74 |

| Multiwax W-445 | Odd- and even-numbered hydrocarbons (peak at C33H68 or C34H70) | 28–29 | 71 |

| Dammars | 5-dammarenolic acid methyl ester (C31H52O3) | 29–30 | 454 |

| Colophony |

Dehydroabietic acid

(C20H28O2) 7-oxo-dehydroabietic acid (C20H26O3) |

21–24 | 316, 328 |

| Gum elemi | α-amyrin / β-amyrin (C30H50O) | 29–30 | 426 |

Note: Each ingredient is identified by the presence of specific compounds at a particular molecular weight (m/z). GC/MSD seemed to have difficulty detecting microcrystalline wax (particularly when beeswax was present in the recipe) as well as the proprietary resins Zonarez B-85 and Piccolyte S-85 (not listed in table).

Table: Amber Kerr, Gwen Manthey, Keara Teeter, Kristin DeGhetaldi, Brian Baade, W. Christian Petersen, and Catherine Matsen

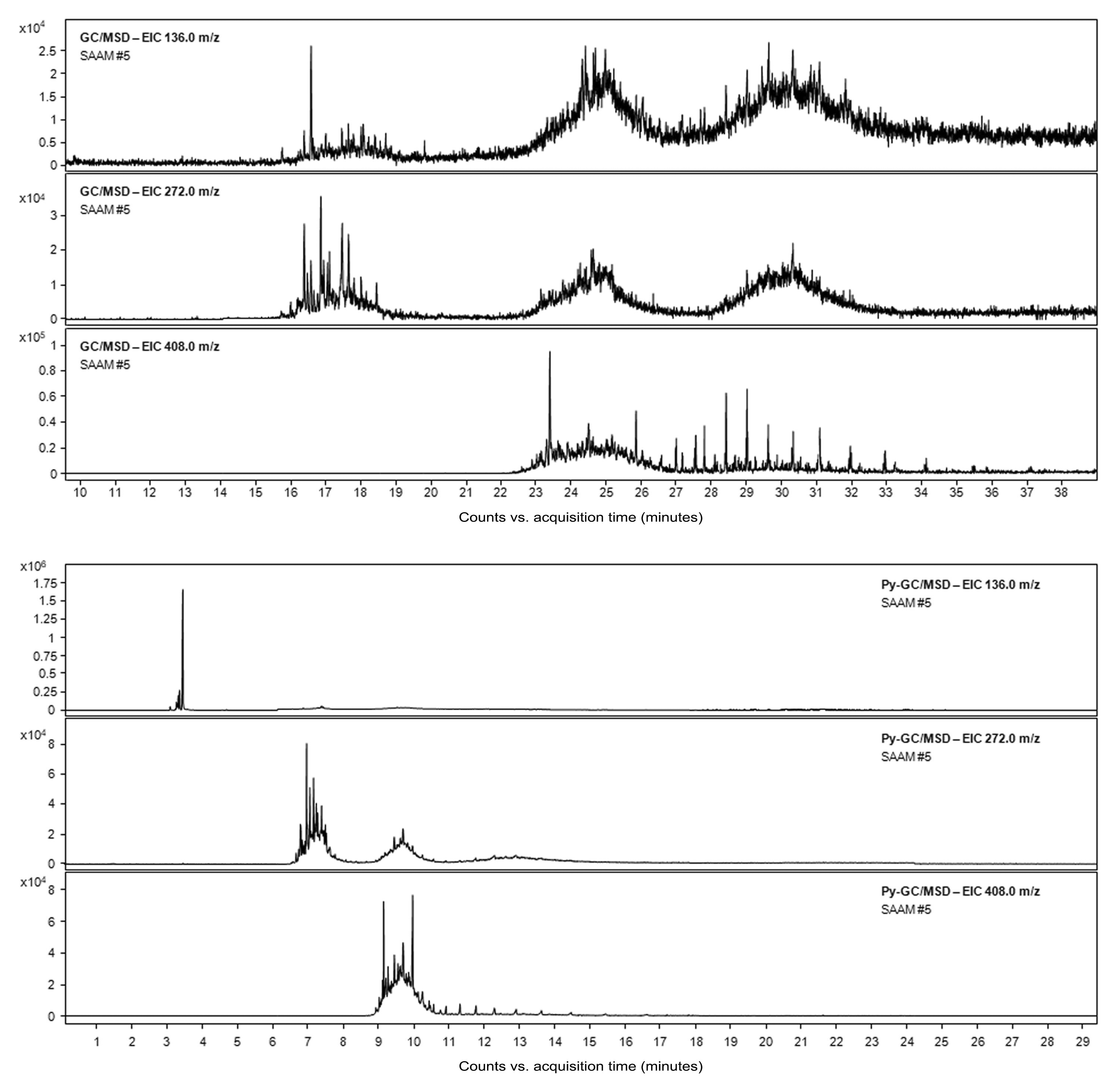

For the final stage of this research, three historical linings and associated SAAM recipes were analyzed with Py-GC/MSD: Oak Trees and SAAM 2; The Lesson and SAAM 4; Plenty and SAAM 5. Raw samples of Zonarez B-85 and Piccolyte S-85 were also pyrolyzed as a control standard for data comparison. The results indicated that Py-GC/MSD was more successful in detecting the odd- and even-numbered hydrocarbons present in microcrystalline wax. This method was also more proficient in detecting the polylimonene monomers, dimers, and trimers associated with the two proprietary resins (table 17.3; see fig. 17.2). After reviewing the GC/MSD data in comparison with the Py-GC/MSD data, the GC/MSD extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) were found to contain “humps” along the baseline that matched the pattern for polylimonene (fig. 17.3). Other recipe ingredients—beeswax, dammar, colophony, and gum elemi—were also clearly identified with Py-GC/MSD.

| Ingredient | Compounds in resins detected with Py-GC/MSD | Retention time (min.) | Ions (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zonarez B-85 | Limonene monomer (C10H16), dimer (C20H32), and trimer (C30H48) | 3–10 | 136, 272, 408 |

| Piccolyte S-85 | Limonene monomer (C10H16), dimer (C20H32), and trimer (C30H48) | 3–10 | 136, 272, 408 |

Note: Both Zonarez B-85 and Piccolyte S-85 were identified by the presence of the acid-catalyzed dimerization and trimerization of limonene.

Table: Amber Kerr, Gwen Manthey, Keara Teeter, Kristin DeGhetaldi, Brian Baade, W. Christian Petersen, and Catherine Matsen

Concluding Thoughts and Moving Forward

In most cases, FTIR is simply not suitable for characterizing most of these potentially complex recipes. It was also difficult to detect the presence of synthetic waxes in many of the samples using GC/MSD. This may depend on the type of wax, the amount, or even the age of the sample itself. Sampling excess wax-resin adhesive from all unidentified textile linings is impractical, but the reconstructions and analysis prove that even when known materials are present, they are not readily identified. It is possible lining mixtures may be characterized by sensorial qualities to the examiner, particularly if they can be compared against the reconstructions. This rough characterization may allow for a generalized prediction of a particular lining’s failure potential, when considered in tandem with the exhibition history and previous condition issues of the painting in question.

This study has provided an understanding of how pervasive wax-resin linings are in the collection, and how late the practice remained in use. The frequency of lining treatments was likely prompted by extensive loan requests and the contemporaneous belief that wax-resin linings were a suitable preventative measure. While this analysis has been useful, many initial questions remain unanswered. We have a foundation with which to test future hypotheses on how these materials deteriorate, although the methods for testing these hypotheses must still be designed. Since the reconstructions were lined, areas of impasto have already been observed to contribute to lining delamination in the unstretched lined mock-ups, raising new questions about environment, tension, and percussive movement.

It is the hope of the authors that these mock-ups and this preliminary study will provide a resource and reference for future fellows and researchers to enrich our collective understanding of the aging and failure mechanisms of wax-resin linings.

Acknowledgments

Support for the two research trips to the Winterthur Museum was provided by the WUDPAC Edward and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Award. WUDPAC and University of Delaware scientists and conservators who assisted with the analysis collection and data interpretation include Dr. Mike Szelewski, Dr. Rosie Grayburn, and Dr. Jocelyn Alcántara-García. The authors would also like to thank Joy Gardiner (Charles F. Hummel Director of Conservation at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library) for releasing this research for publication.

External institutions and private practice conservation studios also donated their time and materials to the SAAM wax-resin lining research project. Most of these donations were coordinated in response to SAAM’s April 2019 “Call for Wax-Resin Materials” posting on the American Institute for Conservation Higher Logic community platform. External collaborators included Lauren Bradley and Josh Summer at the Brooklyn Museum, Barbara Ramsay and Elizabeth Robson at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Andrea Chevalier and Charles Eiben at the Intermuseum Conservation Association, Ann Creager Conservation, Nina A. Roth-Wells LLC, and Pinova Inc., a subsidiary of DRT (Dérivés Résiniques et Terpéniques).

Notes

-

7-oxo-dehydroabietic acid always accompanies dehydroabietic acid, but not vice versa; the former tends to be present only after a sample has degraded and/or been subjected to extreme heat. ↩︎