Adhesive meshes are thin, flexible microstructure nets made from pure methyl cellulose or sturgeon glue—and in the future possibly poly(isobutyl methacrylate). Whereas ready-made glue mixtures like acrylic dispersions or heat-seal adhesives may contain changeable and uncertain ingredients, adhesive meshes consist of homogeneous, constant materials with convincing aging resistance. The bonding procedure is carried out by positioning the mesh in its dry state, activating it with a controlled supply of moisture or solvents, and applying pressure to generate the adhesion. Thus, instead of penetrating the canvas, the adhesive remains discretely in the joint, assuring a regular, permeable adhesive pattern. The method’s advantages further include adjustability of the adhesive strength and increased reversibility. Case studies implementing water-soluble adhesive meshes illustrate the range of application techniques and bonding properties, depending on the choice of adhesive.

28. Reliable Adhesives in New Shape: Canvas Bonding with Self-Supporting Adhesive Meshes

- Mona Konietzny, Dresden University of Fine Arts

- Karolina Soppa, Professor, Bern University of Applied Sciences, Switzerland

- Ursula Haller, Professor, Dresden University of Fine Arts

Introduction

In order to preserve paintings’ authenticity, lining today has become the exception rather than the rule. Nevertheless, the application of a complete or partial textile support is indispensable in the case of severe degradation or damage phenomena. But this presents challenges concerning the choice and application of adhesives. The development of a new canvas bonding technique using microstructure adhesive meshes described in this paper aims at solving complex conservation issues while fulfilling criteria such as purity and long-term stability of adhesives, controllable application, and reversibility.

The choice of materials includes unblended adhesives that have been tested extensively and are established in conservation practice: methyl cellulose, sturgeon glue, and poly(isobutyl methacrylate) (PiBMA). Application is carried out by positioning the dry adhesive mesh on the object or lining fabric, then activating the adhesive with water or organic solvents, and finally joining the parts under pressure until dry. This technique provides a diffusive and reversible bonding, using low amounts of adhesive, water, or solvent, thus assuring a minimally invasive and highly controllable treatment. Strip-lining, attachment of small patches on the back of small holes (e.g., nail holes along the tacking margin), and re-adhering historical linings have all been successfully accomplished.

Production and application of adhesive meshes was the objective of a research project between Bern University of Applied Sciences and APM Technica AG, both Switzerland, and Dresden University of Fine Arts, Germany. The project began in 2018 and was financed by the Swiss Federal Innovation Agency. This paper introduces the development, characteristics, and choice of materials used for adhesive meshes, as well as activation strategies recently tested, based on case studies.

Current Lining Techniques and Materials—Opportunities and Limits

Looking back at the evolution of lining techniques over the last decades, one finds multiple approaches that attempt to reduce the amount of adhesive applied and adhesive penetration, as well as the impact of elevated temperatures, water, or solvents, all of which enable increased reversibility. The most important achievements include Mehra’s nap-bond cold-lining (Mehra, Vishwa R. 1975b. “Nap-Bond Cold Lining on a Low-Pressure Table.” Maltechnik Restauro: Internationale Zeitschrift Für Farb- Und Maltechniken, Restaurierung Und Museumsfragen: Mitteilungen Der IADA 81, no. 2: 87–95.), Heiber’s Geweberasterhaftung (grid adhesion) technique (Heiber, Winfried. 1987. “Die Doublierung mit Geweberasterhaftung.” ZKK Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 1, no. 2: 72–76.), and the more recent mist-lining (van Och, Jos, and René Hoppenbrouwers. 2003. “Mist-Lining and Low-Pressure Envelopes: An Alternative Lining Method for the Reinforcement of Canvas Paintings.” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 17, no. 1: 116–28.). Their common characteristic is the application of the adhesive compound as an openly structured layer on the lining canvas rather than on the original canvas. When dried and solid, it is reactivated by means of heat or solvents.

Adhesives based on synthetic polymers are popular for those and most other lining applications today, including heat-seal adhesives like Beva 371 and different polymer dispersions. However, all are composed of highly complex formulations, prone to segregation, altering mechanical properties, and they often exhibit poor long-term stability.1 Surfactants in acrylic dispersions, for instance, can degrade or migrate from the bulk adhesive, whereas the plasticizer in Beva 371 is basically able to migrate into the painting structure (Cimino, Dafne, Rebecca Ploeger, E. René de la Rie, Christopher W. McGlinchey, Tommaso Poli, Oscar Chiantore, and Johannes A. Poulis. 2020. “Progress in Formulating New Adhesives for Conservation Purposes.” In Supporto e(‘) immagine: Problematiche di consolidamento e di conservazione dei supporti nei dipinti contemporanei: Atti del 8o Congresso internazionale Colore e conservazione, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia, 23–24 november 2018, edited by Barbara Caranza. Saonara, Italy: Il Prato.; Lazzari, M., D. Scalarone, G. Malucelli, and O. Chiantore. 2011. “Durability of Acrylic Films from Commercial Aqueous Dispersion: Glass Transition Temperature and Tensile Behavior as Indexes of Photooxidative Degradation.” Progress in Organic Coatings 70, no. 2: 116–21.). Of utmost concern, though, are modifications of the composition without indication by the manufacturer, as well as renaming and discontinuation of products, resulting in altered working and aging properties (Cimino, Dafne, Rebecca Ploeger, E. René de la Rie, Christopher W. McGlinchey, Tommaso Poli, Oscar Chiantore, and Johannes A. Poulis. 2020. “Progress in Formulating New Adhesives for Conservation Purposes.” In Supporto e(’) immagine: Problematiche di consolidamento e di conservazione dei supporti nei dipinti contemporanei: Atti del 8o Congresso internazionale Colore e conservazione, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia, 23–24 november 2018, edited by Barbara Caranza. Saonara, Italy: Il Prato.; Ploeger, R., C. W. McGlinchey, and E. René de la Rie. 2015. “Original and Reformulated BEVA® 371: Composition and Assessment as a Consolidant for Painted Surfaces.” Studies in Conservation 60, no. 4: 217–26.). In addition, application of synthetic polymer adhesives requires high temperatures (in excess of 60°C) or harmful solvents, which might also pose a risk to paint layers. Although modern techniques emphasize reversibility, inevitable residues may limit options for further treatments.

Toward a New Approach to Canvas Bonding

Based on the concerns outlined above, pure, extensively tested adhesives with good aging properties are preferable as materials for canvas bonding. Methyl cellulose, sturgeon glue, and PiBMA, which so far have not been commonly used for this particular purpose, show good long-term aging behavior and have found broad application in the field of conservation for several decades (see “Characteristics and Materials of Adhesive Meshes” below). However, these adhesives are mostly applied in liquid form, commonly as weak solutions. Owing to the high proportion of water or solvent, such solutions tend to penetrate porous materials like canvas. This may result in a weak bond (Soppa, Karolina, Tilly Laaser, Christoph Krekel, Margaux Genton, and Thuja Seidel. 2014. “Adhesion and Penetration of Sturgeon Glue and Gelatines with Different Bloom Grades.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 17th Triennial Conference: Building Strong Culture through Conservation: Melbourne, 15–19 September 2014, Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland, art. 1313. Paris: ICOM-CC.), heterogeneous adhesive distribution, stiffening and darkening of the canvas, or water-induced shrinkage of the canvas, with subsequent paint delamination.

To overcome the risks related to the application of liquid solutions, solid and dry adhesive films that can be activated have been developed, of which Beva 371 films are the most common. With the aim of minimizing adhesive input and reducing heat-induced risks, we developed adhesive meshes rather than films, made from the materials mentioned above. These can be activated with controlled supply of water or solvent. The method originates from a diploma project’s approach to fix an old lining with sturgeon glue meshes. In this thesis, the manual production and a first application of mesh prototypes were implemented, followed by preliminary tests of the bond strength using different activation parameters (Konietzny, Mona. 2014. “‘Madonna mit Kind’ eines unbekannten Künstlers, Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg. Konservierung eines zweifach doublierten, formatveränderten und großflächig übermalten Leinwandgemäldes.” Diploma thesis, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Dresden., Konietzny, Mona. 2015. “Gewebeverklebung mit Störleimgittern. Erste Anwendung und Überprüfung einer innovativen Technik zur Verbindung von Leinwänden mit Störleim.” Zeitschrift Für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 29, no. 1: 79–94.). The highly promising results initiated the idea to pursue this approach with a dedicated research project.

Characteristics and Materials of Adhesive Meshes

Adhesive meshes are flexible structures made from a single adhesive. Their initial square mesh geometry was recently replaced by a honeycomb design that provides an optimized bonding pattern (fig. 28.1), while reducing adhesive input even further. The material thickness of the adhesive mesh is about 200 μm, and the interspaces have an average diameter of 500 to 600 μm. One square meter of an adhesive mesh weighs between 15 and 30 g, depending on the production process and adhesive.2 The defined honeycomb shape enables an exceptionally uniform distribution of the adhesive throughout the bonding surface. Despite the lack of a carrier material, the meshes have a certain stiffness that allows access to detached layers through gaps or slits.

In contact with water or solvent, the solid meshes become tacky, thereby requiring lower amounts of a liquid phase than solutions do to achieve sufficient adhesion. Proper activation causes only swelling, not dissolution of the mesh, assuring the adhesive remains discretely in the joint without penetrating into the textile. The bond strength can reach similar values to Beva 371 films (65 µm), depending on the activation parameters.3 The bonding characteristics can be adjusted by varying the amount of water or solvent: the more solvent that is applied—up to the point of liquefaction—the stronger the activation and the higher the bond strength tends to be.

Thanks to the mesh structure, a more homogeneous bonding can be achieved, while maintaining higher flexibility and permeability and presumably less tension compared to the adhesive’s application as solution or gel. Furthermore, the reversibility of the bond will be improved due to lower tendency of the adhesive to migrate and penetrate. Depending on the requirements of the individual painting and treatment, the adhesive can be tailored using three materials that differ mainly in activation time and bonding properties.

Methyl cellulose is among the most durable adhesives used in conservation (Feller, Robert L., and Myron Wilt. 1993. Evaluation of Cellulose Ethers for Conservation. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.). The water-soluble, semisynthetic carbohydrate exhibits constant material properties due to its standardized industrial production. Hydrophilic and hydrophobic substituents along the polymer chain can develop affinities to a broad range of substrates of polar and nonpolar nature. The material has been investigated extensively for conservation treatments, with the conclusion that its common perception as a weak adhesive is obsolete (Sindlinger-Maushardt, Kathrin, and Karin Petersen. 2007. “Methylcellulose als Klebemittel für die Malschichtfestigung auf Leinwandbildern - Untersuchungen zur Klebkraft und zur mikrobiellen Resistenz.” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 21, no. 2: 371–82.). Convincing results have been reported for adhering paint flakes on canvas (Soppa, Karolina, Tilly Laaser, Christoph Krekel, Margaux Genton, and Thuja Seidel. 2014. “Adhesion and Penetration of Sturgeon Glue and Gelatines with Different Bloom Grades.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 17th Triennial Conference: Building Strong Culture through Conservation: Melbourne, 15–19 September 2014, Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland, art. 1313. Paris: ICOM-CC., Soppa, Karolina, Stefan Zumbühl, Manon Léchenne, and Anne Muszynski. 2017. “A Study of Thickened Protein Glues for the Readhesion of Absorbent Flaking Paints with Methylcellulose and Wheat Starch Paste.” In Gels in the Conservation of Art, edited by Lora Angelova, Bronwyn Ormsby, Joyce H. Townsend, and Richard C. Wolbers, 96–100. London: Archetype.) and for canvas bonding (Sindlinger-Maushardt, Kathrin, and Karin Petersen. 2007. “Methylcellulose als Klebemittel für die Malschichtfestigung auf Leinwandbildern - Untersuchungen zur Klebkraft und zur mikrobiellen Resistenz.” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 21, no. 2: 371–82.).

For adhesive meshes, two types of Methocel were chosen.4 They differ mainly in degree of polymerization—and thus viscosity. Methocel A15LV is of low viscosity and hence requires a short activation time with low amounts of water. It proved suitable for inaccessible bonding surfaces and water-sensitive materials where only a minimum of humidity is acceptable. Methocel A4C is of medium viscosity but requires more time and water to be activated. The bond strength exceeds that of Methocel A15LV and seems to be equivalent to Beva 371 film (65 µm) bonding (Sindlinger-Maushardt, Kathrin, and Karin Petersen. 2007. “Methylcellulose als Klebemittel für die Malschichtfestigung auf Leinwandbildern - Untersuchungen zur Klebkraft und zur mikrobiellen Resistenz.” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 21, no. 2: 371–82.). Consequently, its use is recommended in cases where bonding surfaces are accessible, water input can be controlled, and a high bond strength is desired. Due to the delayed response to humidity, Methocel A4C might be advantageous for larger areas that need to be bonded, as well as objects that do not require climate control. Methyl cellulose meshes are particularly suitable for paintings that are sensitive to heat, as no elevated temperatures are required for activation.

Sturgeon glue is a traditional adhesive and still in frequent use in conservation.5 Sturgeon glue is gaining popularity in modern paintings conservation thanks to its good adhesive properties and has been investigated for paint adhesion on canvas (Sindlinger-Maushardt, Kathrin, and Karin Petersen. 2007. “Methylcellulose als Klebemittel für die Malschichtfestigung auf Leinwandbildern - Untersuchungen zur Klebkraft und zur mikrobiellen Resistenz.” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 21, no. 2: 371–82.; Soppa, Karolina, Tilly Laaser, Christoph Krekel, Margaux Genton, and Thuja Seidel. 2014. “Adhesion and Penetration of Sturgeon Glue and Gelatines with Different Bloom Grades.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 17th Triennial Conference: Building Strong Culture through Conservation: Melbourne, 15–19 September 2014, Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland, art. 1313. Paris: ICOM-CC.), tear mending (Flock, Hannah. 2014. Neue Untersuchungen zur Rissschließung in Leinwandbildträgern: Uni- und biaxiale Zugprüfungen an Prüfkörpern aus verklebtem Leinengarn und -gewebe sowie freien Klebstofffilmen. Kölner Beiträge zur Restaurierung und Konservierung von Kunst- und Kulturgut, Digitale Edition Band 2. Cologne: CICS/FH Köln. https://epb.bibl.th-koeln.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/601/file/Flock_MA.pdf.), and canvas bonding using glue solutions (Geißinger, Karin, and Christoph Krekel. 2007. “Leim aus Hecht- und Karpfenschwimmblasen–eine mögliche Alternative Zu Störleim?” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 21, no. 2: 317–29.; Mecklenburg, Marion F., L. Fuster-López, and Silvia Ottolini. 2012. “A Look at the Structural Requirements of Consolidation Adhesives for Easel Paintings.” In Adhesives and Consolidants in Painting Conservation, edited by Angelina Barros D’Sa, Lizzie Bone, Rhiannon Clarricoates, and Alexandra Gent, 7–23. London: Archetype.). As a material of natural origin, with variations in raw material and processing (Soppa, Karolina. 2018. “Die Klebung von Malschicht und textilem Bildträger. Untersuchung des Eindringverhaltens von Gelatinen sowie Störleim und Methylcellulose bei der Klebung von loser Malschicht auf isolierter und unisolierter Leinwand mittels vorhergehender Fluoreszenzmarkierung – Terminologie, Grundlagenanalyse und Optimierungsansätze.” PhD diss., Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart.), it can display a range of bonding properties. The glue does slightly discolor over time, unlike methyl cellulose (Pataki-Hundt, Andrea. 2018. “Characteristics of Natural and Synthetic Adhesives.” In Konsolidieren und Kommunizieren. Materialien und Methoden zur Konsolidierung von Kunst- und Kulturgut im interdisziplinären Dialog, edited by Angela Weyer, 122–30. Petersberg, Germany: Michael Imhof Verlag.). Sturgeon glue remains sufficiently water soluble over time, and its adhesive strength barely changes (Geißinger, Karin, and Christoph Krekel. 2007. “Leim aus Hecht- und Karpfenschwimmblasen–eine mögliche Alternative Zu Störleim?” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 21, no. 2: 317–29.; Przybylo, Maria. 2006. “Langzeit-Löslichkeit von Störleim. Tatsache oder Märchen?” Beiträge zur Erhaltung von Kunst- und Kulturgut, Verband der Restauratoren 1: 117–23.). It is prone to rapid response to fluctuating RH and, in the long run, to increased crystallinity in films (Schellmann, Nanke C. 2007. “Animal Glues: A Review of Their Key Properties Relevant to Conservation.” Studies in Conservation 52, no. S1: 55–66.). This fact limits the application of sturgeon-glue meshes preferably to smaller areas or objects in controlled environmental conditions. On the other hand, considerable tack develops within a very short activation time with only small amounts of activation water. Thermal energy (35°C) further mobilizes the gel, leading to better adhesion—albeit at the cost of propagating penetration into the canvas (Konietzny, Mona. 2015. “Gewebeverklebung mit Störleimgittern. Erste Anwendung und Überprüfung einer innovativen Technik zur Verbindung von Leinwänden mit Störleim.” Zeitschrift Für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 29, no. 1: 79–94.). Elevated temperatures can thus help to reduce the amount of activation water required. Like methyl cellulose, sturgeon glue is capable of adhering to various materials, including natural wax (Fischer, Andrea, and Margarete Eska. 2011. “Joining Broken Wax Fragments: Testing Tensile Strength of Adhesives for Fragile and Non-Polar Substrates.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 16th Triennial Meeting, Lisbon, Portugal, 19–23 September 2011: Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland and Catherine Antomarchi. Almada, Portugal: Critério; Paris: ICOM-CC.).

PiBMA Degalan PQ 611 (formerly Plexigum PQ 611)6 is soluble in aliphatic hydrocarbon solvents such as isooctane or petrol ether without any aromatics. Therefore, acrylic meshes qualify for water-sensitive painting structures, such as canvas that tends to shrink or water-soluble paint layers. Activation of the acrylate requires comparably small amounts of solvents that can be sprayed or vaporized. Lower bond strength can be achieved without solvents by applying elevated temperatures just above the glass transition temperature of 33°C (Brandt, Julia, and Carina Volbracht. 2018. “Doublierung als letzter Ausweg für ein großformatiges Leinwandgemälde des frühen 19. Jahrhunderts. Versuch eines minimalinvasiven Eingriffs.” VDR Beiträge zur Erhaltung von Kunst- und Kulturgut 1: 34–44.). Owing to the brittleness of PiBMA, a stiffening effect occurs when used for canvas bonding. This might be an advantage when the movement of a highly degraded textile support needs to be reduced. Degalan PQ 611 N provides very good adhesion to polar and nonpolar substrates alike, for instance, to both wax (Fischer, Andrea, and Margarete Eska. 2011. “Joining Broken Wax Fragments: Testing Tensile Strength of Adhesives for Fragile and Non-Polar Substrates.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 16th Triennial Meeting, Lisbon, Portugal, 19–23 September 2011: Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland and Catherine Antomarchi. Almada, Portugal: Critério; Paris: ICOM-CC.) and cellulosic materials. Concerning long-term material behavior, PiBMA-based adhesives are stable in terms of discoloration, but they may cross-link to a certain amount. Nevertheless, the solubility likely remains in aliphatic hydrocarbon solvents with a small proportion of aromatics (Feller, Robert L. 1984. “Thermoplastic Polymers Currently in Use as Protective Coatings and Potential Directions for Further Research.” AICCM Bulletin 10, no. 2: 5–18.; Down, Jane L. 2015. “The Evaluation of Selected Poly(Vinyl Acetate) and Acrylic Adhesives: A Final Research Update.” Studies in Conservation 60, no. 1: 33–54.). However, PiBMA has not yet been processed into stable adhesive meshes due to its brittleness, which would require extensive adjustments to the method.

Production of Adhesive Meshes

So far, we have manually produced sturgeon-glue and methyl cellulose meshes by using silicone molds. For this purpose, the structure of a polyester monofilament mesh is imprinted in the flattened surface of a kneadable two-component silicone mass. After complete vulcanization, the mesh is taken off and adhesives (in the form of a 20 w/w gel) are filled in using a spatula. Excess material is scraped off. After two to three hours the dried mesh is removed.7

This early technique of producing adhesive meshes can easily be implemented with materials available in conservation studios. However, obtaining uniform results is more difficult with respect to mold and mesh shaping. Greater precision and homogeneity can be achieved by computerized numerical control (CNC) machining, such as laser cutting of the silicone molds (fig. 28.2). A feasible process for a standardized, larger-scale production of adhesive meshes has been refined within the course of the current research project.

Application of Adhesive Meshes—Two Case Studies

The application of adhesive meshes aims at reinforcing degraded canvas with an auxiliary support, such as strip-lining, or reattaching of loosened parts along the edges of detached historical linings. The technique was successfully applied in case studies using meshes made from sturgeon glue and methyl cellulose. Examples of treated paintings can be found at the Swiss National Museum and the Fondation Beyeler, both in Switzerland, and the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen in Germany. In addition, different European universities and private conservation studios implemented adhesive meshes for canvas stabilization—and even for full-scale lining.8 In the following, two case studies are described to exemplify activation procedures according to the conservation target and the accessibility of the bonding surfaces.

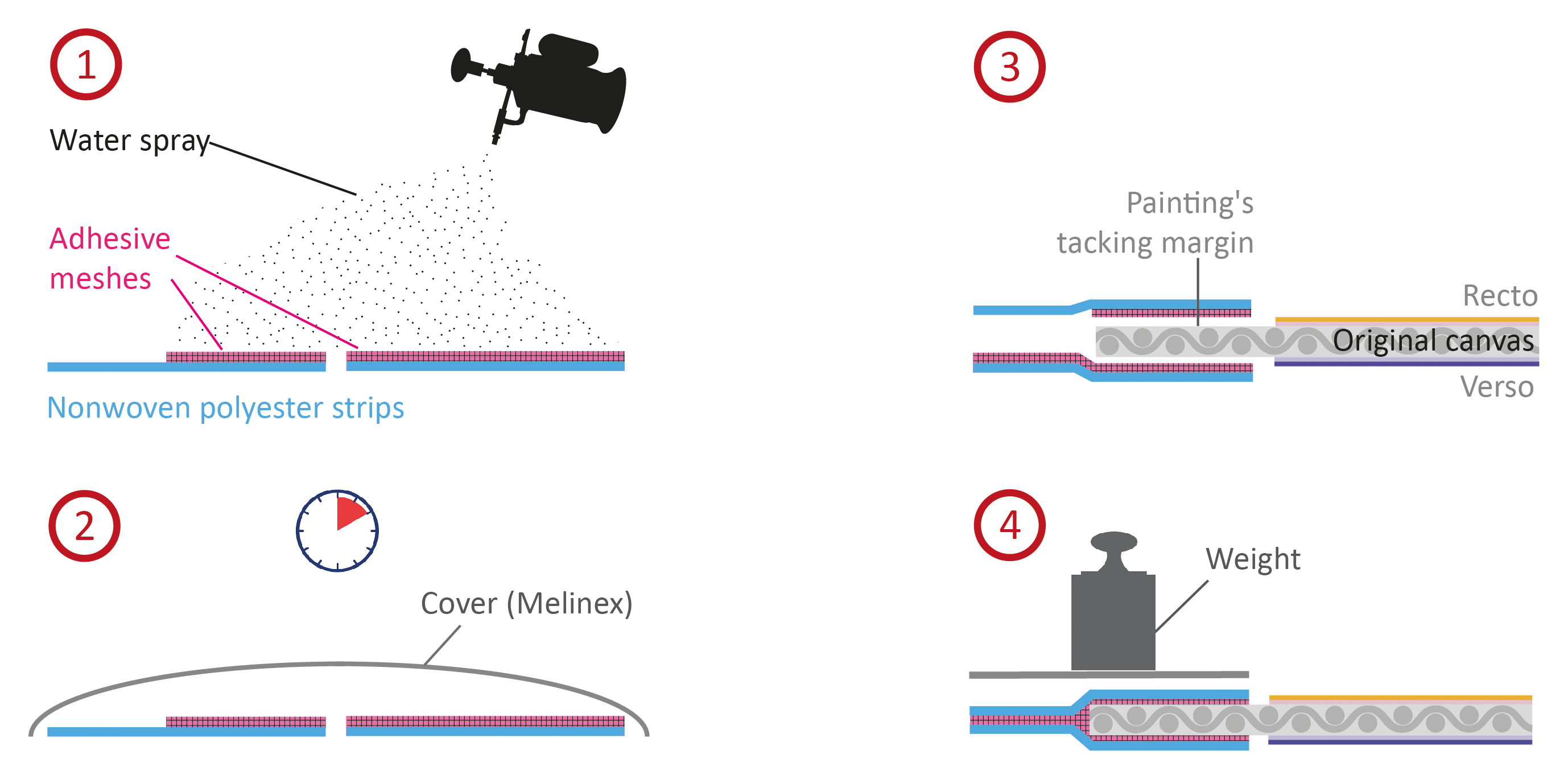

For strip-lining, the bonding interfaces are readily accessible. This intervention was realized on a medium-format double-sided canvas painting (fig. 28.3).9 A sandwich system of two nonwoven polyester strips was chosen.10 Methyl cellulose meshes made from Benecel A4C11 were used, since high bond strength and adhesive stability in variable environmental conditions were required and the canvas was not sensitive to water. To prepare the bonding material, methyl cellulose meshes made with laser-cut silicone molds were partly activated by slightly moistening the nonwoven polyester before placing the adhesive meshes on the nonwoven strips and drying them under pressure (fig. 28.4). Activation was then initiated by spraying water with a precision pump sprayer (fig. 28.5). The meshes were left for ten minutes as methyl cellulose takes up water slowly.12 Coverage with a Melinex film without direct contact prevented the meshes from drying (see fig. 28.5).

The activation process was repeated twice to apply a total amount of about 3 ml water per 100 square centimeters of mesh, resulting in a relatively high water input that was almost completely absorbed by the mesh. To achieve the bonding, the activated strips were then placed below and on top of the tacking margin of the painting’s canvas (see fig. 28.3) and left to dry for twenty-four hours under pressure (20 g/cm²) with blotting paper interleaves. After complete drying, it was possible to pull the tacking margin taut enough to remount the painting on a new stretcher, proving that methyl cellulose meshes are capable of generating a sufficiently strong bond between two textiles.

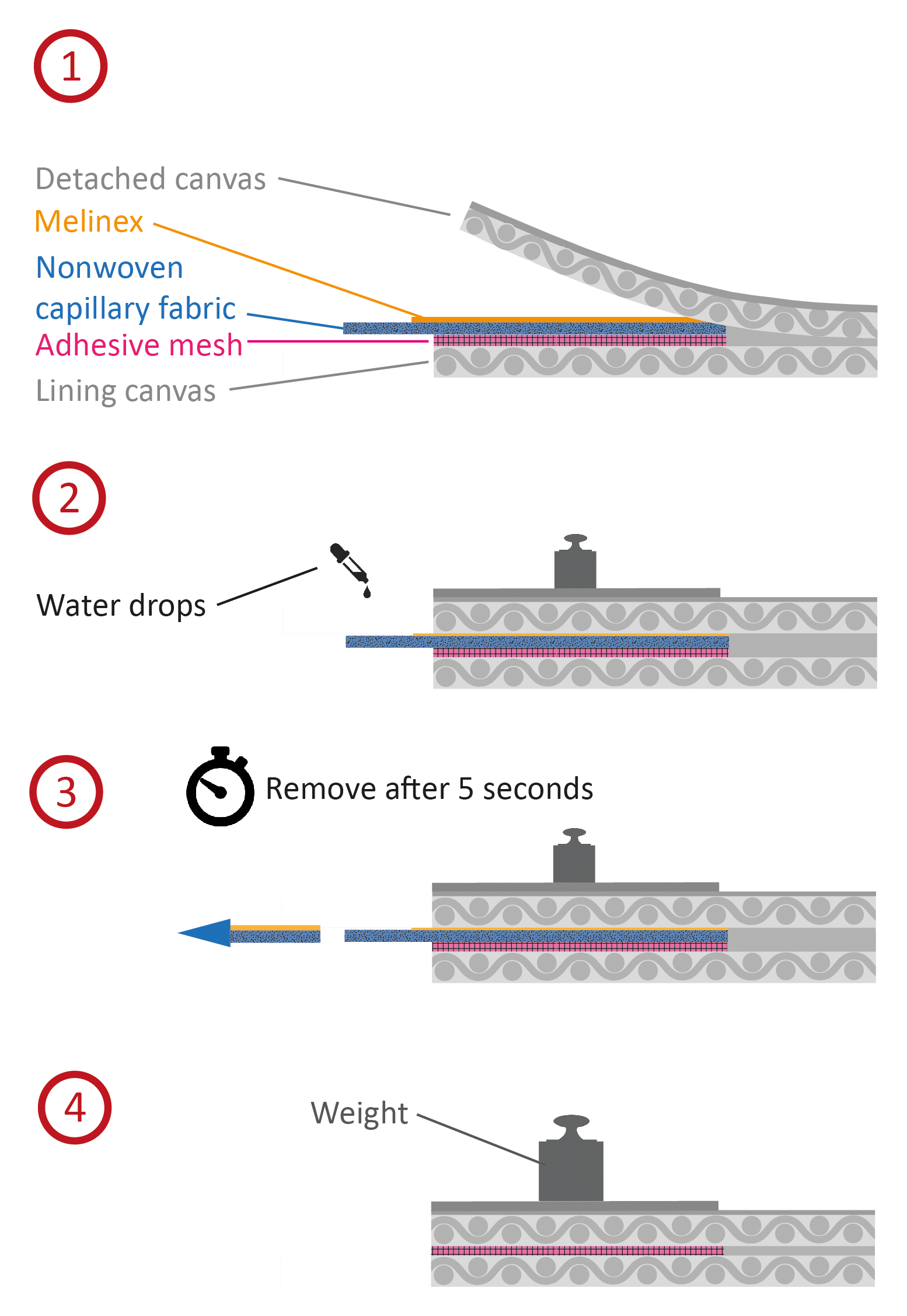

A different activation approach is necessary when access to the bonding surface is limited. This phenomenon often occurs with lined paintings, such as that shown in figure 28.6, where the edge of the original canvas is detached locally from the lining canvas. To maintain the historical lining and stabilize loosened areas, insertion of the adhesive was possible only through small gaps, which is why adhesive meshes provided a suitable approach. Activation has to be carried out quickly to avoid excess water in the painting structure. Therefore, Methocel A15LV meshes and sturgeon-glue meshes are suitable due to the short time required and the reduced need for water for activation.

The application is identical for both adhesives. To uniformly activate the inserted dry mesh, a nonwoven capillary fabric13 is used. This material can transport water along its directed fibers and then disperse it onto the mesh. A protrusion of some millimeters allows access for the water to be applied. The adhesive mesh and the capillary fabric are first cut to match the shape of the detachment. Then both the mesh and the capillary fabric are inserted between the canvas layers (fig. 28.7). An additional layer of Melinex on top is advisable to protect the original canvas from being wetted, and a light weight is used to keep the layers in contact during the procedure.

Then water is added onto the nonwoven fabric’s edge until it is completely saturated. Immediately after complete saturation—within about five seconds—the fabric and Melinex are removed with a quick pull to prevent the mesh from sticking to the fabric. Finally, pressure is applied (10 g/cm²) until the adhesive has dried. This activation method reduces the amount of water twentyfold compared to the spray activation described above. The resulting bond was found to be strong enough to fix the canvas to the lining fabric anew, yet for reversibility, the lining can easily be peeled off.14

These case studies demonstrate two possible methods of adhesive mesh activation. Further strategies for water or solvent application to accessible bonding surfaces include brushes, especially those with a high absorptive capacity. However, repeated brush applications should be avoided, as the meshes might break, whereas onetime application produces a water film on the mesh without penetrating the underlying canvas. Instead of the nonwoven capillary fabric, other absorptive materials can be used for poorly accessible bonding surfaces. Blotting paper works well for small areas, but since it takes up water rather slowly the risk of sticking to the mesh is higher.

Spray-activated adhesive meshes that were frozen prior to application were also successfully implemented. Frozen meshes are stable for a short period but can be inserted into narrow gaps, where they immediately melt and trigger the bonding.15 Other tools, such as ultrasonic or high-pressure nebulizers and airbrushes, are suitable for both accessible and inaccessible areas. Water drops for a punctual activation can be achieved by microdosing systems. In combination with acrylic meshes, activation with solvent vapor is another feasible option.

Conclusion

The development of adhesive meshes for canvas bonding aims at minimizing the amount of adhesive and solvent required and achieving a homogeneous adhesive distribution, while preserving high reversibility with minimal residues. Commercial lining adhesives suffer from well-known problems, including undisclosed ingredients, changes in formulation, and aging behavior. Adhesives commonly used in painting conservation, on the other hand, tend to comply with decisive criteria such as proven long-term stability and good adhesion to a broad range of common substrates. This has set the choice for their use as suitable mesh materials. Each of the three adhesives chosen—methyl cellulose of two viscosity types, sturgeon glue, and PiBMA—exhibits individual qualities for making them suitable for specific applications, and the three available options together cover a broader range of applicable cases.

The activation technique by which water or solvent is applied as spray, through nonwoven capillary fabrics and the like, ensures excellent control and adjustability of the adhesive bond. Bonding characteristics are determined by activation parameters like amount of water or solvent and optional application of elevated temperatures. So far, the technique using water-soluble adhesive meshes has proved suitable for canvas painting treatments such as lining, strip-lining, and the repair of detached historical linings.

To provide adhesive meshes for conservators, a reliable production process for the manufacturing of methyl cellulose and sturgeon-glue meshes was developed during the recent research project, and these are now provided by APM Technica AG.16 Further investigations to evaluate adhesive meshes for canvas bonding will be the focus of an ongoing PhD project17 covering activation strategies and bonding characteristics, particularly adhesive strength and penetration as a function of activation parameters, as well as the long-term behavior of adhesive mesh bonds. The results will provide fundamental application guidelines and help to define the potential of adhesive meshes. Apart from canvas bonding, fixing loose paint18 and treating other materials, such as textiles19 or paper,20 are other application fields that seem highly feasible.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following persons and organizations for their assistance with our research: APM Technica AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland; Innosuisse – Swiss Innovation Agency Art Technological Laboratory; Conservation Program and Materiality in Art and Culture research focus at Bern University of Applied Sciences, Switzerland; Bern University of the Arts, Switzerland; Swiss National Museum, Collection Center, Affoltern am Albis, Switzerland; Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland; Doerner Institute, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich, Germany; Museumslandschaft Hessen-Kassel, Germany; Jonathan Debik and Sonja Bretschneider of Dresden, Germany; and Christina Robens and Verena Graf of Vienna, Austria.

Notes

-

See Bianco, Lisa, Massimiliano Avalle, Alessandro Scattina, Paola Croveri, Cesare Pagliero, and Oscar Chiantore. 2015. “A Study on Reversibility of BEVA®371 in the Lining of Paintings.” CULHER Journal of Cultural Heritage 16, no. 4: 479–85.; Cimino, Dafne, Rebecca Ploeger, E. René de la Rie, Christopher W. McGlinchey, Tommaso Poli, Oscar Chiantore, and Johannes A. Poulis. 2020. “Progress in Formulating New Adhesives for Conservation Purposes.” In Supporto e(') immagine: Problematiche di consolidamento e di conservazione dei supporti nei dipinti contemporanei: Atti del 8o Congresso internazionale Colore e conservazione, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia, 23–24 november 2018, edited by Barbara Caranza. Saonara, Italy: Il Prato.; Witte, E. de, S. Florquin, and M. Goessens-Landrie. 1984. “Influence of the Modification of Dispersions on Film Properties.” Studies in Conservation 29, supp1: 32–35.; Down, Jane L. 2015. “The Evaluation of Selected Poly(Vinyl Acetate) and Acrylic Adhesives: A Final Research Update.” Studies in Conservation 60, no. 1: 33–54.; Howells, Rachel, Aviva Burnstock, Gerry Hedley, and Stephen Hackney. 1984. “Polymer Dispersions Artificially Aged.” In Adhesives and Consolidants: Contributions to the 1984 IIC Congress, Paris, edited by Norman S. Brommelle, Elizabeth M. Pye, Perry Smith, and Gary Thomson, 36–43. London: International Institute for Conservation. Also published in Studies in Conservation 29, no. 1: 36–43.; Lazzari, M., D. Scalarone, G. Malucelli, and O. Chiantore. 2011. “Durability of Acrylic Films from Commercial Aqueous Dispersion: Glass Transition Temperature and Tensile Behavior as Indexes of Photooxidative Degradation.” Progress in Organic Coatings 70, no. 2: 116–21.; McGlinchey, Christopher, Rebecca Ploeger, Annalisa Colombo, Roberto Simonutti, Michael Palmer, Oscar Chiantore, Robert Proctor, Bertrand Lavédrine, and E. René de la Rie. 2011. “Lining and Consolidating Adhesives: Some New Developments and Areas of Future Research.” In Adhesives and Consolidants for Conservation: Research and Applications; Proceedings of Symposium 2011, October 17–21, 265–84. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute.; Ploeger, R., C. W. McGlinchey, and E. René de la Rie. 2015. “Original and Reformulated BEVA® 371: Composition and Assessment as a Consolidant for Painted Surfaces.” Studies in Conservation 60, no. 4: 217–26.; Silva, Miguel F., María Teresa Doménech-Carbó, and Laura Osete-Cortina. 2015. “Characterization of Additives of PVAc and Acrylic Waterborne Dispersions and Paints by Analytical Pyrolysis-GC-MS and Pyrolysis-Silylation-GC-MS.” Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 113: 606–20.. ↩︎

-

This is less than the weight of Beva 371 film (25 µm): 43 g/m². ↩︎

-

The bond strength has also been evaluated for sturgeon glue meshes (Konietzny, Mona. 2015. “Gewebeverklebung mit Störleimgittern. Erste Anwendung und Überprüfung einer innovativen Technik zur Verbindung von Leinwänden mit Störleim.” Zeitschrift Für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 29, no. 1: 79–94.) and methyl cellulose meshes (Konietzny, Mona, Ella Dudew, Ursula Haller, Nadim Scherrer, and Karolina Soppa. 2022. “Klebstoffgitter aus Methylcellulosen für die Konservierung textiler Bildträger: Anwendungseigenschaften und Kennwerte im Vergleich zu Verklebungen mit BEVA® 371-Filmen.” Zeitschrift Für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 35, no. 1 (2022): 180–94. and ongoing research). ↩︎

-

Methocel has been produced by DuPont since 2019, and formerly by Dow Chemical (until 2017) and DowDuPont (2017–19). ↩︎

-

Sturgeon glue is commonly made by conservators from the sturgeon’s swimming bladder. The German company Störleim Manufaktur manually produces ready-made sturgeon-glue pellets. ↩︎

-

Degalan has been produced by Röhm GmbH since 2019. Before that, manufacturers were Degussa AG (until 2007) and Evonik Industries (2007–19). ↩︎

-

A detailed description of the process can be found in Konietzny, Mona. 2014. “‘Madonna mit Kind’ eines unbekannten Künstlers, Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg. Konservierung eines zweifach doublierten, formatveränderten und großflächig übermalten Leinwandgemäldes.” Diploma thesis, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Dresden. and Konietzny, Mona, Karolina Soppa, and Ursula Haller. 2018. “Canvas Bonding with Adhesive Meshes. Poster.” In Konsolidieren und Kommunizieren. Materialien und Methoden zur Konsolidierung von Kunst- und Kulturgut im interdisziplinären Dialog. Internationale Tagung der HAWK Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaft und Kunst in Hildesheim, 25–27 Januar 2018, edited by Angela Weyer, 169. Petersberg, Germany: Michael Imhof Verlag. https://hornemann-institut.de/german/epubl_poster49.php#doi.. ↩︎

-

Lining was performed by Sonja Bretschneider in 2019, in a private studio in Dresden, Germany, with adhesive meshes made from a mixture of Benecel A4C and sturgeon glue. ↩︎

-

Strip-lining performed in 2018 by Jonathan Debik and Mona Konietzny, in a private studio in Kassel, Germany. ↩︎

-

The following materials consisting of 100% polyester were used: nonwoven polyester (70 g/m²), purchased from GMW–Gabi Kleindorfer, D-84186 Vilsheim (on the painting’s reverse); and Parafil RT 20 (20 g/m²), produced by TWE Dierdorf GmbH & Co. KG, D-56269 Dierdorf, purchased from Deffner & Johann, D-97520 Röthlein (on the painting’s front). ↩︎

-

Benecel A4C corresponds to Methocel A4C and is produced by Ashland Inc. ↩︎

-

A shorter time of one to five minutes was later found to be sufficient for proper activation. ↩︎

-

We used the nonwoven capillary fabric Paraprint OL 60, consisting of viscose and acrylic binder, produced by TWE Dierdorf GmbH & Co. KG, D-56269 Dierdorf, purchased from Deffner & Johann, D-97520 Röthlein. ↩︎

-

Peel tests on canvas joined with sturgeon-glue meshes confirmed that activation with minimal water results in easily separable bonds (Konietzny, Mona. 2015. “Gewebeverklebung mit Störleimgittern. Erste Anwendung und Überprüfung einer innovativen Technik zur Verbindung von Leinwänden mit Störleim.” Zeitschrift Für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 29, no. 1: 79–94.). ↩︎

-

Frozen sturgeon-glue meshes were implemented for partially re-adhering an old lining during a semester project at Bern University of the Arts’ conservation program in 2018. ↩︎

-

https://www.apm-technica.com; send inquiries to info@apm-technica.com. Adhesive meshes are also available from Störleim Manufaktur: http://www.stoerleim-manufaktur.de/. ↩︎

-

The PhD project of Mona Konietzny is based at Dresden University of Fine Arts, Germany. ↩︎

-

The adhesion of wax-based paint on canvas on an artwork by Hermann Nitsch was performed with methyl cellulose meshes made from Benecel A4C by Christina Robens and Verena Graf in a private studio in Vienna, Austria, in 2019. ↩︎

-

The reattachment of silk decorations on a textile support was performed by Julia Dummer in 2019 at Museumslandschaft Hessen-Kassel, Germany. ↩︎

-

Different paper objects have been treated using Klucel G meshes during semester projects at the Bern University of the Arts’ conservation program in 2019, and for a bachelor’s thesis at the University of Applied Sciences in Cologne (Hehl, Sabrina. 2019. “Restaurierung einer historischen Spielschachtel aus dem Deutschen Spielearchiv Nürnberg.” Bachelor’s thesis, Technische Hochschule Köln.). ↩︎