Glue paste has been the most widely used lining adhesive in the Southern European tradition. This research was devoted to studying the mechanical performance and failure mechanisms of mock-up linings made with selected simplified glue-paste recipes when subjected to changing environments as a function of the materials and application techniques used. For this purpose, different qualities of wheat and rye flours were tested, mixed with selected animal glues in different proportions. The elimination of additives from the recipes studied provided coherence and clearer evaluation of results. Two representative lining canvases were selected, and linings were carried out following the Italian tradition. The lined mock-ups were subjected to RH cycles, and the impact on the mechanical, chemical, and biological properties of the lined paintings was reported, with special attention given to the effects of the degree of milling, the cereal protein content of the flours, and the weave density of the lining fabrics.

51. An Insight into the Limits and Possibilities of the Biological, Chemical, and Mechanical Performance of Glue-Paste Lined Paintings

- Laura Fuster-López, Professor, Instituto Universitario de Restauración del Patrimonio, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

- Cecil Krarup Andersen, Associate Professor and Head of Paintings Conservation, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation, School of Conservation, Copenhagen

- Nicolas Bouillon, Chemist, Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP), Marseille, France

- Fabien Fohrer, Entomologist, Centre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP), Marseille, France

- Matteo Rossi-Doria, Painting Conservator, C.B.C. Conservazione Beni Culturali

- Mikkel Scharff, Professor, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation, School of Conservation, Copenhagen

- Kate Seymour, Professor, Stichting Restauratie Atelier, Maastricht, the Netherlands

- Ángel Vicente-Escuder, Professor, Instituto de Tecnología de los Materiales, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

- Dolores Julia Yusà-Marco, Associate Professor, Instituto Universitario de Restauración del Patrimonio, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

- Sofía Vicente-Palomino, Associate Professor, Instituto Universitario de Restauración del Patrimonio, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

Introduction

A variety of materials have been used in glue-paste linings throughout history, and this lining type is found on a significant number of the paintings in collections worldwide. Recipes varied from country to country and epoch to epoch. Cereal flours and animal glues were usually the main ingredients, either because they were readily available or simply owing to tradition. A variety of different additives (molasses, vinegar, Venetian turpentine, garlic, etc.) were commonly included in recipes, aiming to enhance performance or to prevent mold growth (Hackney, Stephen, Joan Riefsnyder, Mireille Te Marvelde, and Mikkel Scharff. 2012. “Lining Easel Paintings.” In Conservation of Easel Paintings, edited by Joyce Hill Stoner and Rebecca Rushfield, 415–52. Abingdon: Oxon; New York: Routledge.; Macarrón, Ana, Ana Calvo, and Rita Gil. 2016. “Documentation of European Recipes for Glue Paste Linings.” In Sources on Art Technology: Back to Basics, 139–40. London: Archetype.).

Glue-paste linings can be long-lasting, but they can also lead to further degradation. It has remained unclear why some of these linings fail while others remain well preserved. In the last twenty-five years, there has been a significant interest in understanding the performance and aging of glue-paste linings. Some studies have analyzed the role of each component and given some insight into the bond performance of the adhesive mixture (Ackroyd, Paul. 1995. “Glue-Paste Lining of Paintings: An Evaluation of the Bond Performance and Relative Stiffness of Some Glue-Paste Linings.” In Lining and Backing: The Support of Paintings, Paper and Textiles: Papers Delivered at the UKIC Conference, 7–8 November 1995, edited by Andrew Durham, 83–91. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works., Ackroyd, Paul. 1996. “Glue-Paste Lining of Painting: An Evaluation of Some Additive Materials.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation: 11th Triennial Meeting, Edinburgh, 1–6 September 1996: Preprints, 231–38. London: James & James.; Young, Christina, and Paul Ackroyd. 2001. “The Mechanical Behavior and Environmental Response of Paintings to Three Types of Lining Treatment.” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 22: 85–104.; Young, Christina, Roger Hibberd, and Paul Ackroyd. 2002. “An Investigation into the Adhesive Bond and Transfer of Tension in Lined Canvas Paintings.” In 13th ICOM-CC Triennial Meeting, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 22–27 September 2002, 370–78. London: James & James.). The research presented here shows how varying the dominant ingredients of the glue-paste recipe influences the mechanical performance (bond strength, stiffness, etc.) and degradation processes (biodeterioration) of lined canvas paintings. The impact of cyclic RH on the biological and physical stability of the laminate structure is also reported.

The Role of Glues and Flours in the Mechanical Performance of Glue-Paste Linings

Glues and flours are the two main components of glue-paste adhesives. Their complex structure, properties, and stability suggested a need to prioritize the research aimed at understanding their behavior and interaction before considering the role of the different additives cited in treatises and recipe books.

The study of protein glues in the conservation field has attracted some attention in recent years. Obtained from the skin and bones of animals through different preparations and purification treatments, their chemical, physical, and mechanical properties are largely influenced by the chemical structure of the protein and its denaturation process. Protein glues generally have high cohesive strength and stiffness in comparison to synthetic adhesives, as previous research has shown (Mecklenburg, Marion F. 1982. “Some Aspects of the Mechanical Behavior of Fabric Supported Paintings: Report to the Smithsonian Institution.” Unpublished report, Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Washington, DC. Reprinted in Dawn V. Rogala, Paula T. DePriest, A. Elena Charola, and Robert J. Koestler, eds. The Mechanics of Art Materials and Its Future in Heritage Science, 107–29. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.11342126.; Andersen, Cecil K., and Laura Fuster-López. 2019. “Insight into Canvas Paintings’ Stability and the Influence of Structural Conservation Treatments.” In The Mechanics of Art Materials and Its Future in Heritage Science: A Seminar and Symposium, 13–20. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.).

The molecular weight (size and length of the chains of the protein), the content of the helix structures formed during renaturation, and the type of intra- and intermolecular bonds in the protein as a function of the proline and hydroxyproline content determine the cohesive strength and the viscosity of the glue solution (Schellmann, Nanke C. 2007. “Animal Glues: A Review of Their Key Properties Relevant to Conservation.” Studies in Conservation 52, no. S1: 55–66.). The stiffness of gelatin leads to the classification into different Bloom grades, which are also an indication of mechanical properties (Melià Angulo, Ana, Laura Fuster-López, and Angel Vicente Escuder. 2017. “Study of the Mechanical Properties of Selected Animal Glues and Their Implication When Designing Conservation Strategies.” CeROArt: Conservation, exposition, restauration d’objets d’art, HS 2017. https://doi.org/10.4000/ceroart.5152.). Hide glues are also responsive to humidity fluctuations, developing high internal stresses if restrained and subjected to desiccation and losing all strength and undergoing biodeterioration above 70% RH (Mecklenburg, Marion F. 1982. “Some Aspects of the Mechanical Behavior of Fabric Supported Paintings: Report to the Smithsonian Institution.” Unpublished report, Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, Washington, DC. Reprinted in Dawn V. Rogala, Paula T. DePriest, A. Elena Charola, and Robert J. Koestler, eds. The Mechanics of Art Materials and Its Future in Heritage Science, 107–29. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.11342126.). Together, these characteristics mean that animal glues play a major role in the behavior and long-term performance of glue-paste adhesives.

The second main component in glue pastes is flours, in which starch, proteins, and lipids are the most relevant components. Starch has functional properties such as solubility, water-holding capacity, swelling power, viscosity, and consistency, all of which largely depend on the amylose-amylopectin ratio as well as on the size of their granules as a function of the botanical origin and nature of the starch. The protein content also plays a major physicochemical role in the rheological behavior of the adhesive mixture (García Castillo, Ana M. 2016. “Study of the Physical, Chemical and Mechanical Properties of Glue-Paste Lining Adhesives.” MA diss., Universitat Politècnica de València.).

Biological, Chemical, and Mechanical Performance of Glue-Paste Linings

After preliminary research dedicated to the study of several protein glues with different Bloom grades and some flours with different protein content, mock-ups with eight different combinations of materials were prepared (fig. 51.1). For this purpose, one cowhide glue, one rye flour, and three wheat flours were selected (table 51.1). Two different fabrics were used as lining support, and a commercial primed linen canvas with a ground layer of titanium white/zinc oxide bound in oil was used to simulate a canvas painting. Glue-paste mixtures were tested according to the ratio shown in table 51.2. Peel and tensile tests were run in order to record the adhesion and cohesion forces at different RH conditions for unaged and aged samples. Biodeterioration and insect infestation tests were also carried out (Fuster-López, Laura, Cecil Krarup Andersen, Nicolas Bouillon, Fabien Frohrer, Matteo Rossi-Doria, Mikkel Scharff, Kate Seymour, Ángel Vicente-Escuder, Sofia Vicente-Palomino, and Dolores J. Yusà-Marco. 2017. “Glue-Paste Linings: An Evaluation of Some Biological, Chemical and Mechanical Aspects of a Traditional Technique.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation, 18th Triennial Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 4–8 September 2017: Linking Past and Future; Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland. Paris: ICOM.).

| Type | Light microscopy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10× | 25× | |||||

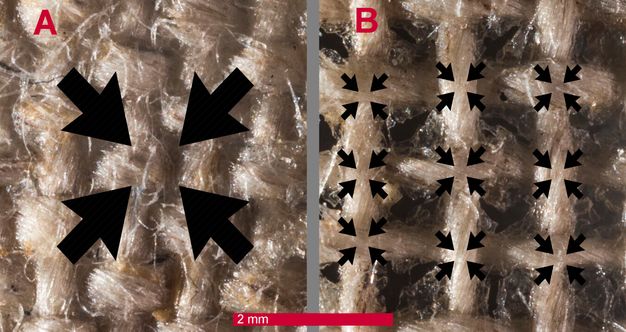

| Open-weave washed linen fabric: 9 × 9 threads/cm2 (CTS 2297) |

|

|

||||

| Close-weave washed linen fabric: 15 × 15 threads/cm2 (CTS 1111) |

|

|

||||

| Type | Brand | Form | Bloom grade | Viscosity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hide glue | Kremer 63010 | Pellets | 240–250 | 80 mPA | ||

| Type | Brand | Protein content (%) | Wet gluten (%) | Amylose-amylopectin ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-milled Candeal white wheat, Type 45 | El Corte Inglés | 10–11 | 21.5 | 0.45 | ||

| Fine-milled Manitoba white wheat, Type 55 | Finestra sul Cielo | 14 | 27.3 | 0.44 | ||

| Rough-milled semiwhole wheat, Type 80 | Minoterie DOM | 10–11 | 24.8 | 0.35 | ||

| Rough-milled semiwhole rye, Type 70 | Minoterie DOM | 7 | — | 0.35 | ||

| Glue-paste mixture (ratio 1:6) | Lining fabric | Mock-up painting: primed canvas | Unaged samples | Aged samples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glue | Flour | ||||

| 63010 Kremer | Wheat Manitoba Type 55 | Open-weave linen canvas: 9 × 9 threads/cm2 (CTS 2297) | Primed linen canvas, titanium white/zinc oxide bound in oil as ground layer (Claessens, Belgium) | WM-O-U | WM-O-A |

| Wheat Type 45 | WT55-O-U | WT55-O-A | |||

| Wheat Type 80 | WT80-O-U | WT80-O-A | |||

| Rye Type 70 | Rye-O-U | Rye-O-A | |||

| Wheat Manitoba Type 55 | Close-weave linen canvas: 15 × 15 threads/cm2 (CTS 1111) | WM-C-U | WM-C-A | ||

| Wheat Type 45 | WT55-C-U | WT55-C-A | |||

| Wheat Type 80 | WT80-C-U | WT80-C-A | |||

| Rye Type 70 | Rye-C-U | Rye-C-A | |||

Note: O = open, C = closed, A = aged, U = unaged.

Table: Courtesy of the research team

Results (table 51.3) evidenced the influence of lining materials and adhesive formulations on the mechanical properties and the tendency toward biodeterioration. Peel tests showed an average peel force of 6.52 N/cm in close-weave canvases and 4.98 N/cm in open-weave ones. In general, aging significantly increased (by 10%–27%) the force needed to peel off the close-weave lining fabrics in all cases, except for those where Type 45 wheat flour (WT45) had been used. Conversely, the average peel force decreased (by 32%–39%) in linings made of open-weave canvases except for those where WT45 was used. Results also showed that the type of flour and the degree of milling, as well as the density of the lining canvas, strongly influence the mechanical and dimensional stability of glue-paste linings and determine the failure risk of the paint layers. This approach to the possible influence of weave tightness on crack formations has been recently witnessed in a study of four paintings by Pablo Picasso (Fuster-López, Laura, F. C. Izzo, Cecil Krarup Andersen, Alison Murray, Anna Vila, Marcello Picollo, L. Stefani, Rayez Jimenez, and Elena Aguado-Guardiola. 2020. “Picasso’s 1917 Paint Materials and Their Influence on the Condition of Four Paintings.” Springer Nature Applied Sciences 2, no. 12, art. 2159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03803-x.).

| Samples tested in weft direction | Lining canvas | Average peel force (50–250 mm) (N/cm) | Standard deviation (N/cm) | Minimum force (N/cm) | Maximum force (N/cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaged samples | Rye Type 70 | Close weave | 5.46 | 0.90 | 3.63 | 8.02 |

| Wheat Type 80 | 6.42 | 1.06 | 4.04 | 9.46 | ||

| Wheat Type 45 | 5.44 | 1.92 | 2.04 | 9.63 | ||

| Wheat Manitoba Type 55 | 7.41 | 1.50 | 3.76 | 13.35 | ||

| Rye Type 70 | Open weave | 7.40 | 1.86 | 4.00 | 11.69 | |

| Wheat Type 80 | 8.40 | 1.72 | 4.96 | 12.94 | ||

| Wheat Type 45 | 2.26 | 0.39 | 1.67 | 4.17 | ||

| Wheat Manitoba Type 55 | 5.05 | 0.83 | 3.18 | 7.62 | ||

| Aged samples | Rye Type 70 | Close weave | 6.80 | 1.02 | 4.89 | 10.14 |

| Wheat Type 80 | 6.91 | 1.06 | 4.79 | 10.20 | ||

| Wheat Type 45 | 4.31 | 1.20 | 2.39 | 8.24 | ||

| Wheat Manitoba Type 55 | 9.43 | 1.27 | 6.74 | 15.34 | ||

| Rye Type 70 | Open weave | 5.29 | 1.47 | 3.00 | 11.34 | |

| Wheat Type 80 | 5.67 | 1.06 | 3.44 | 8.62 | ||

| Wheat Type 45 | 2.38 | 0.33 | 1.78 | 3.46 | ||

| Wheat Manitoba Type 55 | 3.40 | 0.42 | 2.68 | 5.08 | ||

Note: Tested using ASTM D1876-01 standard; T-type specimens in Shimadzu universal testing machine, 1 kN load cell.

Table: Courtesy of the research team

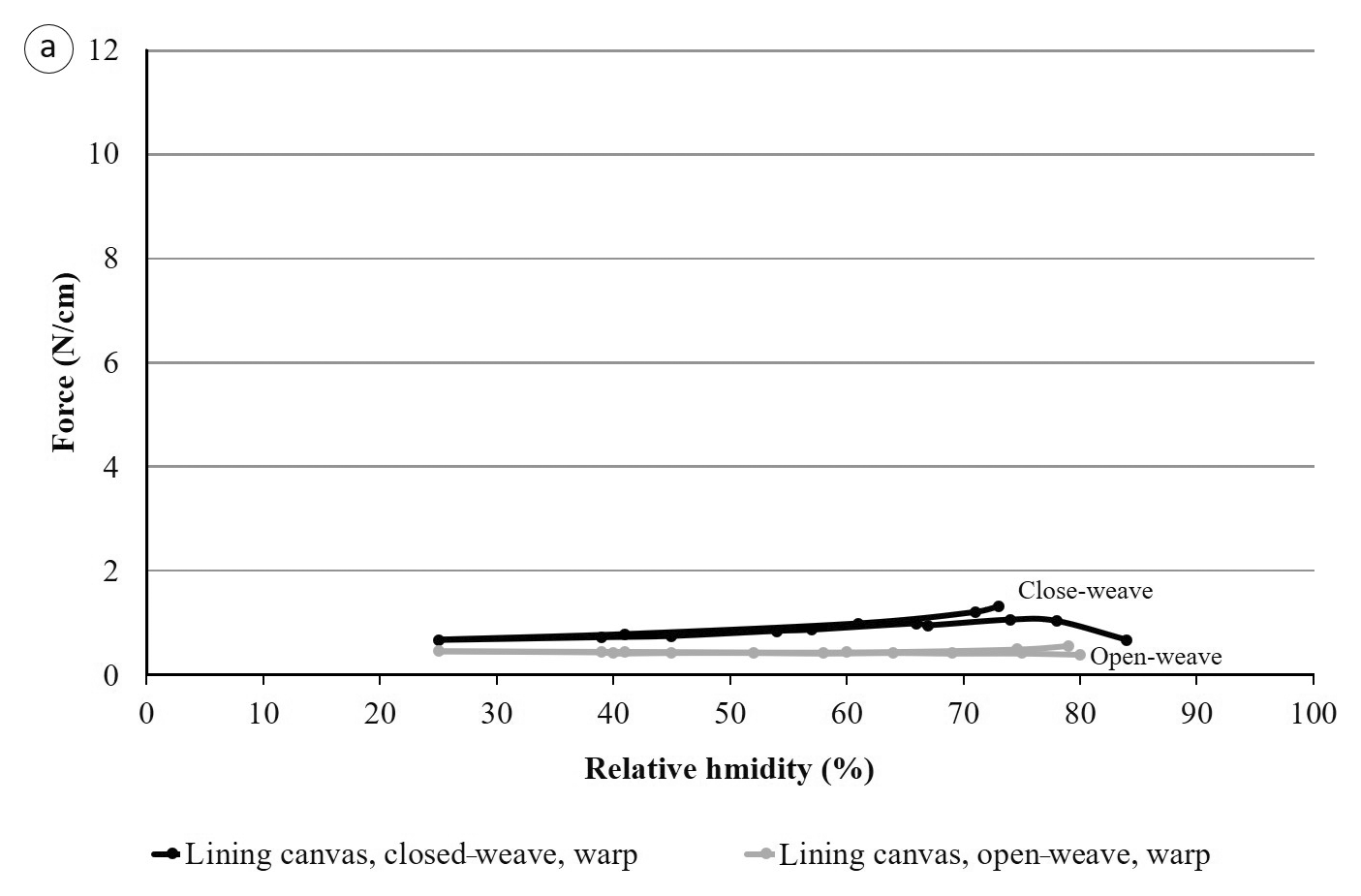

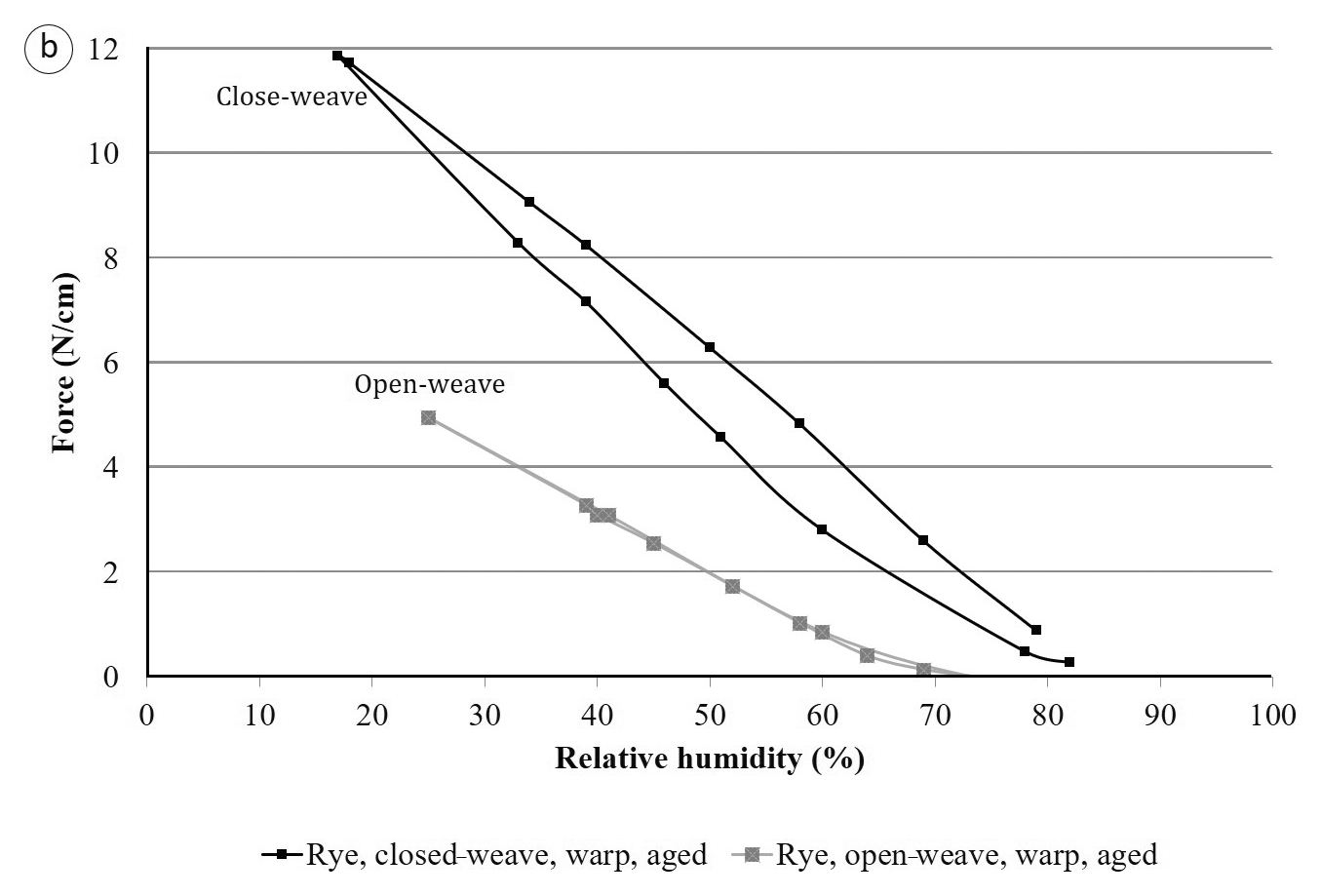

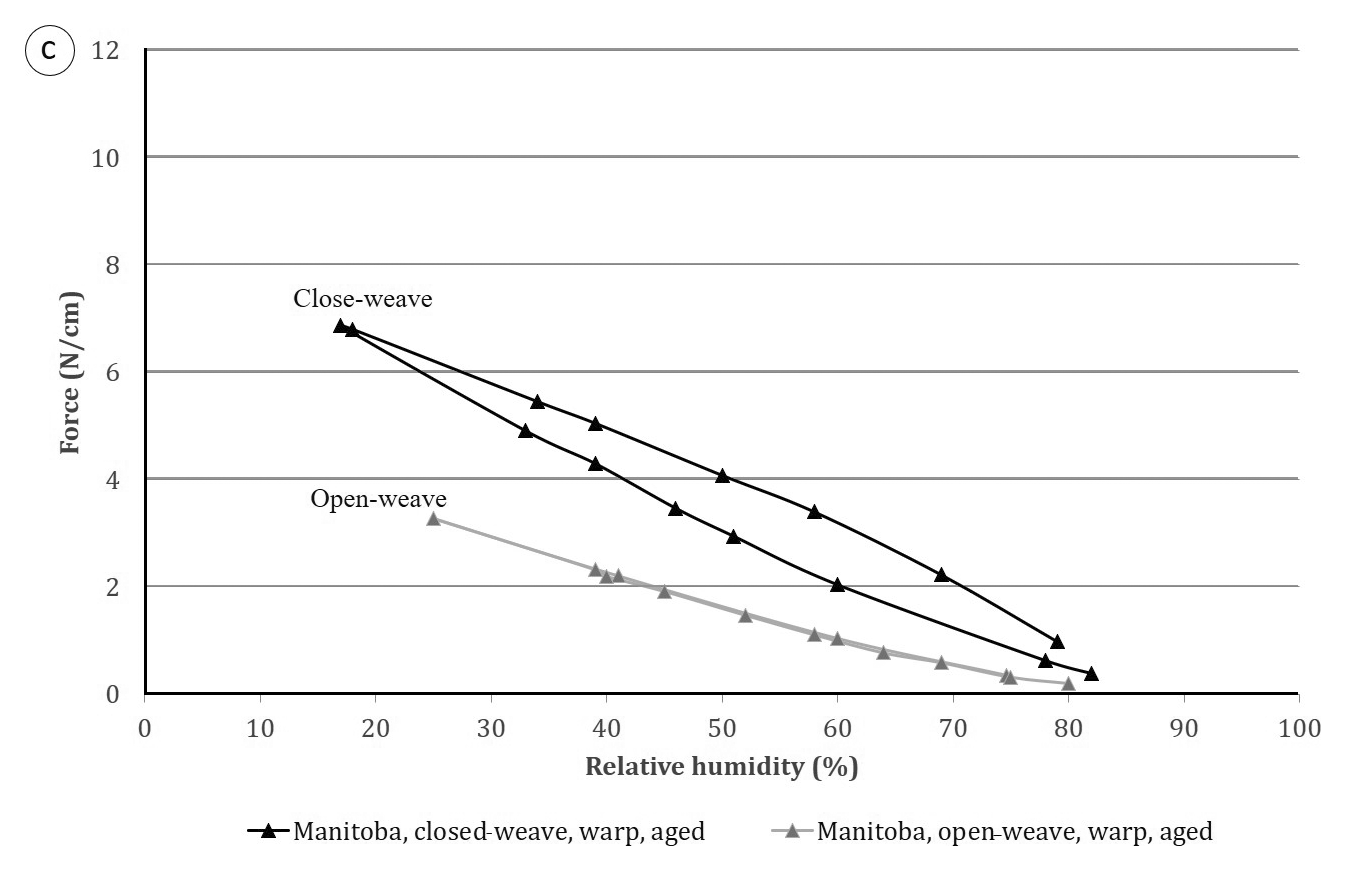

Figure 51.2 shows the restraint tests of different lining fabrics and glue-paste linings. While the force development in the restrained raw canvases when subjected to different RH was similar for both canvas densities tested, significant differences can be observed when the same textile is used as lining fabric in combination with the different glue-paste formulations. For example, adhesive mixtures containing rye Type 70 (7% protein content) develop twice the force when used in combination with close-weave fabrics than when used with open-weave fabrics over a wide range of RH conditions (fig. 51.2b). These values drop to half for both open- and close-weave fabrics when Type 55 (Manitoba) wheat flour is used (fig. 51.2c). In addition, it was observed that among all the combinations tested, closely woven canvases and semiwhole flour–based recipes induce the highest contraction forces in restrained samples, leading to significant risk of cracking and delamination (fig. 51.3).

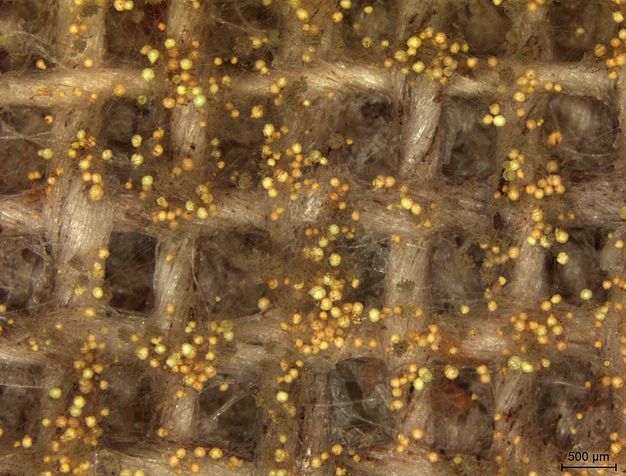

Results evidenced that biodegradation is governed by the flour milling and flour-glue ratio, and by the nature of the starch and protein when the flour-glue ratio is kept constant. Mold growth and pest infestation tests evidenced that glue-paste linings containing semiwhole flours are more sensitive to RH than those made from fine-milled white flours—meaning a greater tendency toward biodeterioration at high RH. Again, the weave geometry of the lining canvas influences the results (fig. 51.4). Close-weave and open-weave canvases are both affected by biodeterioration; open weave-canvases seem to be more prone to contamination by mold but slightly less vulnerable to degradation by insects. Concerning mold, the second layer of glue paste applied from the reverse after the laying on of the lining canvas can act as a better hydrophilic substrate for mold growth. A possible explanation for less infestation is that Stegobium paniceum is a lucifugous insect, so the exposure to light caused by open-weave interstices can disrupt the act of laying eggs.

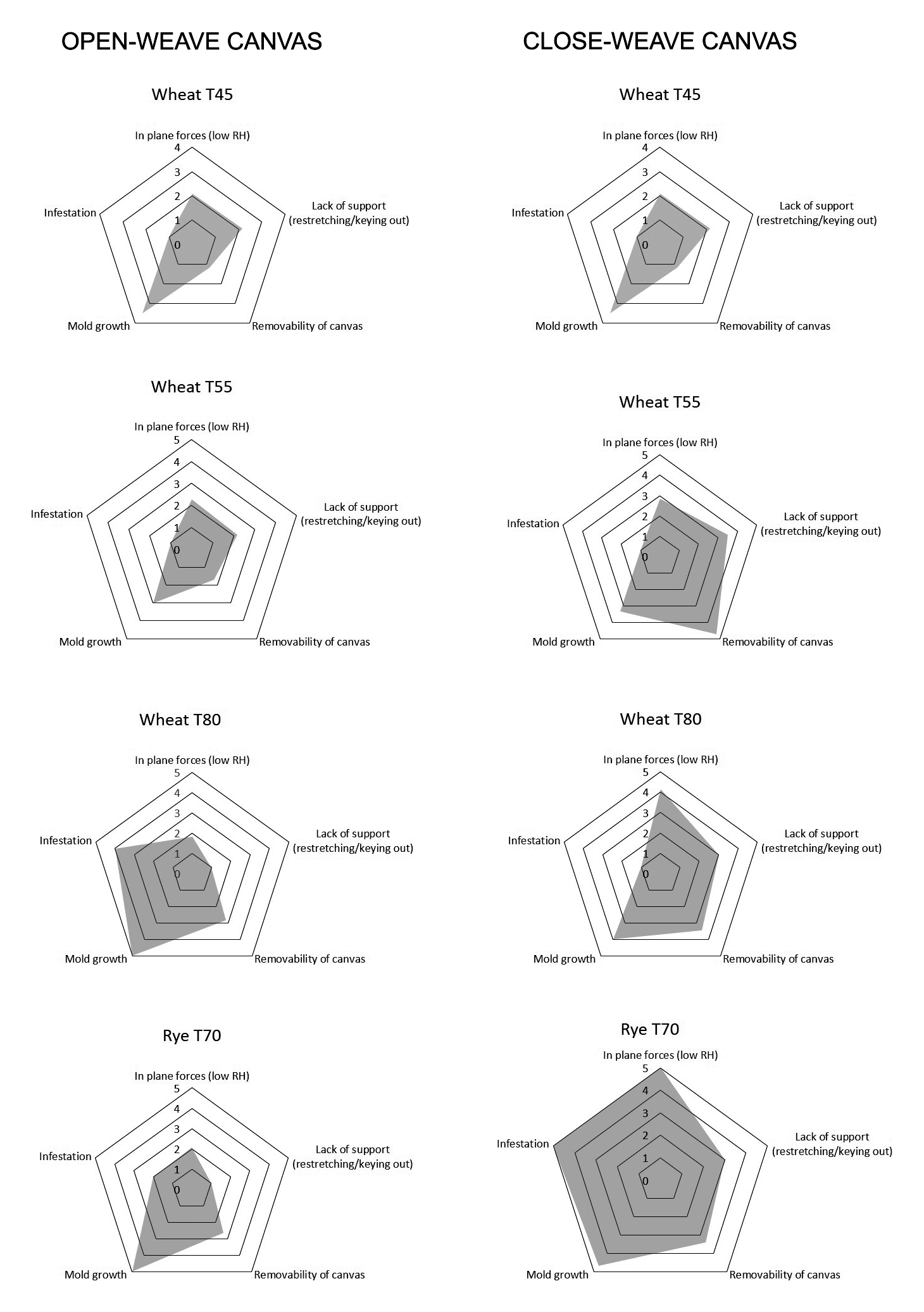

The need to agree on objective parameters that allow the comparison of the different variables considered when studying materials for a given treatment has been suggested by Cecil Krarup Andersen in this publication. Such parameters could help conservators make informed decisions based on the mid- to long-term vulnerability of the materials used. Figure 51.5 shows different star diagrams corresponding to the eight glue-paste linings studied. Values of 1 to 5 are given for each risk factor, with 1 being low risk and 5 high risk. This means that numeric values measured for each factor (Fuster-López, Laura, Cecil Krarup Andersen, Nicolas Bouillon, Fabien Frohrer, Matteo Rossi-Doria, Mikkel Scharff, Kate Seymour, Ángel Vicente-Escuder, Sofia Vicente-Palomino, and Dolores J. Yusà-Marco. 2017. “Glue-Paste Linings: An Evaluation of Some Biological, Chemical and Mechanical Aspects of a Traditional Technique.” In ICOM Committee for Conservation, 18th Triennial Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 4–8 September 2017: Linking Past and Future; Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgland. Paris: ICOM.) are normalized to fit this scale.

The aspects considered are as follows:

-

Buildup of in-plane forces with low RH—higher numbers correspond to higher forces.

-

Lack of support offered by the lining when restretching or keying out—higher numbers correspond to lower stiffness/less support.

-

Removability of canvas—higher numbers correspond to greater force required for removal.

-

Mold growth—higher numbers correspond to greater tendency for mold growth.

-

Pest infestation—higher numbers correspond to greater tendency for pest infestation.

As they depict a risk scale, these star diagrams can be considered either a representation of the stability of each formulation or evidence of their vulnerability.

Conclusions

In this research, several lining-adhesive formulations made of glues and flours were tested. Results evidenced that the choice of materials has a strong impact in the vulnerability of the lined painting in the mid- to long term, which could explain the different conditions of glue-paste linings typically present. It was shown that the weave geometry of fabrics influences the adhesion, dimensional response, and vulnerability to pest infestation of the lined paintings. As a rule, open-weave lining canvases seem to exhibit less mechanical degradation than closer-woven ones. In addition, keeping the glue-to-paste ratio constant made it possible to observe that the type of flour also contributes to the dimensional response and the tendency toward pest infestation and mold growth in glue-paste linings. Rye-based formulations were shown to be the most vulnerable ones—those that require the most restrictive environmental conditions for their long-term stability.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MICINN/FEDER) (HAR20112417). Special thanks go to the Laboratory of the National Museum of Natural History (Paris), Cerelab (Aiserey, Côte d’Or, France), Microscopy Service and Instituto Tecnología de los Materiales at UPV, the Smithsonian Institution and Dr. Marion F. Mecklenburg, CTS (Spain), Claessens (Belgium), SIT-Transport (Spain), and Agar-Agar, Claessen S.L (Spain). Ana M. García and M. Pilar Amate are also acknowledged for their help in the preliminary testing of glues and flours.