Wax-resin linings were introduced to Japan at the end of the 1960s and subsequently were applied to many oil paintings. However, due to their disadvantages, they fell out of use in Japan around 2000. Now, some linings applied decades ago need further treatments, and we needed to understand their material properties in order to appropriately conserve them. This research began with compiling the disseminations of wax resin for lining into Japan, which were derived from the most common recipe used at that time. On that basis, various recipes of wax resin were reconstructed and removal experiments performed. It was revealed that the formulation, amount, and types of resin used in wax resins influenced how the mixtures could be removed. The fact that not all components of wax resin are always removed and, moreover, not uniformly removed, calls for great care in the future treatments of oil paintings lined with wax resin in the past.

50. Various Recipes of Wax Resin for Lining Used in Japan and How the Recipe Affects Removal

- Saki Kunikata, PhD Candidate, Conservation and Restoration, Department of Conservation, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts

- Takayasu Kijima, Emeritus Professor, Conservation and Restoration, Department of Conservation, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts

- Masahiko Tsukada, Professor, Conservation Science, Department of Conservation, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts

Introduction

Japanese conservation of oil paintings began to take shape at the end of the 1960s, when Japanese conservators and conservation scientists who had studied the conservation of oil paintings abroad returned to Japan. Wax-resin linings composed a major part of the techniques they brought into Japan. From then on, this lining method was applied frequently in Japan, where the climate is humid year round. However, as the disadvantages—such as darkening and the difficulty of retreatment—gradually became clearer, the use of wax resin for lining declined, eventually falling out of use in Japan around 2000. Since then, information about its use had not been published in detail, and the recipes were often handled much like trade secrets in Japan. Now the linings, which were applied decades ago, are partly detaching from some paintings, which now need further treatments.

This poster sheds light on how Japanese conservators restored oil paintings using wax resin as lining adhesives in the past, focusing on their various recipes through research done by conducting personal interviews and related bibliographic surveys. As the adhesives are reconstructed and the removal experiments performed, we should gain a better understanding of their material properties in order to choose or propose appropriate ways to conserve paintings treated this way in the past.

Wax-Resin Recipes for Lining Used in Japan

As a first step, interviews on the composition of wax resin and the ways in which it was applied were conducted with conservators who had treated oil paintings in the 1970s and 1980s in Japan using this method. In particular, the authors interviewed conservators who had been involved with the War Record Paintings Conservation project, which was an enterprise of national importance at that time (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, ed. 1977. Senso kirokuga shūfuku hōkoku 戦争記録画修復報告, Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art.). These conservators made significant contributions to the establishment of Japanese oil paintings conservation.

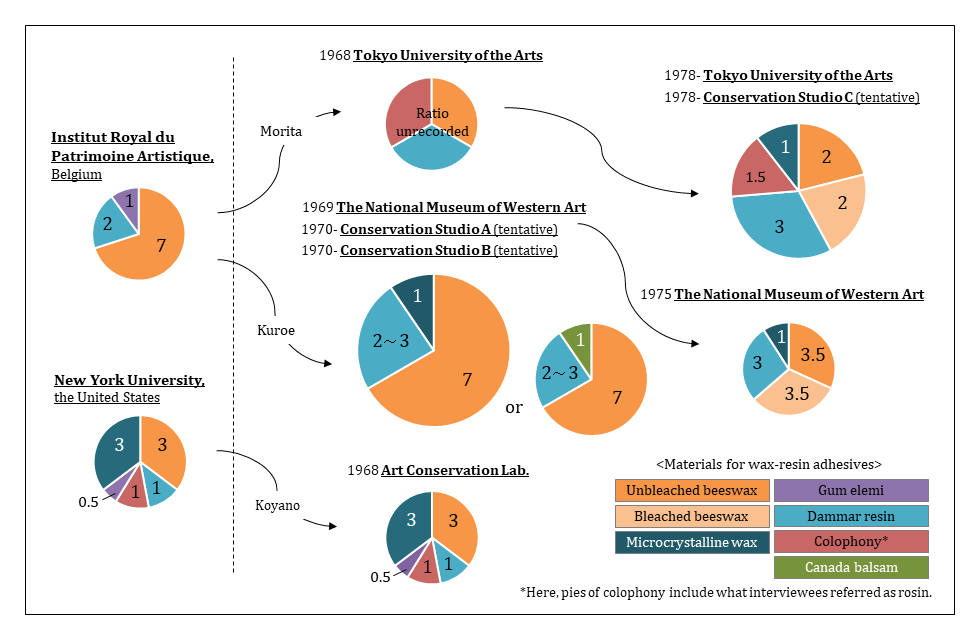

Figure 50.1 shows various recipes of wax resin obtained through the interviews and the related bibliographic surveys. Wax-resin linings were introduced to Japan via two different routes: from Belgium’s Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique (Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage [KIK-IRPA]) and from the United States’ New York University (NYU).1 Most of the recipes used in Japan originated from Georges Messens’s recipe, used at KIK-IRPA. Tsuneyuki Morita and Mitsuhiko Kuroe studied under Messens (Kuroe, Mitsuhiko. 1969. Yomigaeru meiga no tame ni―Shufuku-minarai no kiよみがえる名画のために―修復見習いの記. Tokyo: Bijutsu shuppansha 美術出版社., Kuroe, Mitsuhiko. 1975. Bi wo mamoru―Enaoshi-kagyo美を守る―絵直し稼業, Tokyo: Tamagawa University Press 玉川大学出版部.),2 and they brought his recipe and method to Japan in the late 1960s.

Morita and Kuroe said that it was difficult to get gum elemi at that time in Japan, so they had to find a substitute. One chose colophony because it strengthens the adhesive property and has excellent compatibility with beeswax. The other chose microcrystalline wax—the first synthetic material introduced for wax-resin lining in Japan. It appears that the mainstream wax-resin recipe in Japan then became 7 parts beeswax, 2 or 3 parts dammar resin, and 1 part microcrystalline wax. Most conservators continued to use wax resin for lining over the next two decades, but the modification of the lining adhesive recipe had already been completed in the 1970s. There were few who used ready-made wax resin, although it was available.

Experimental Removal of Wax-Resin Adhesive

Based on the recipes shown in figure 50.1, six formulas of the lining adhesives were prepared for the experiments. As the test pieces, 10 cm square pieces of linen canvas faced with Japanese Tengujo paper on one side were prepared. They were impregnated with the recipes shown in table 50.1 from the fabric side and labeled A through F. On the reverse (uncovered) side, a 1 ml drop of mineral spirit was applied. The drop was covered with blotting paper, and a glass plate and weight were placed on top for thirty seconds. This operation was repeated fifteen times for each piece. After the solvent evaporated completely, the weight loss was measured and the removal amount and rate (percentage) of each sample were compared.

| Sample | Wax |

Quantity (part) |

Resin |

Quantity (part) |

Other |

Quantity (part) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Unbleached beeswax | 7 | Dammar resin | 2 | Microcrystalline wax | 1 | |

| B | Unbleached beeswax | 7 | Dammar resin | 4 | Microcrystalline wax | 1 | |

| C | Unbleached beeswax | 7 | Dammar resin | 2 | Gum elemi | 1 | |

| D | Unbleached beeswax | 7 | Dammar resin | 2 | Colophony | 1 | |

| E | Unbleached beeswax | 7 | Dammar resin | 2 | Canada balsam | 1 | |

| F | Unbleached beeswax | All | — | — | — | — | |

Ten test pieces were prepared for each adhesive (A–F), and half of them were subjected to artificial aging. The heat aging was carried out in an Espec LHU-113 Benchtop Temperature/Humidity Chamber at 55°C and 45% RH for three months. This aging condition was used by Gustav Berger in 1972 to test adhesives used in the consolidation of paintings. According to the reference, the heat aging at 55°C could keep the objects below the melting point (and possible critical deterioration point) of resins (Berger, Gustav A. 1972b. “Testing Adhesives for the Consolidation of Paintings.” Studies in Conservation 17, no. 4: 173–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1505565.). The mean value of the removal rate for each recipe was calculated as follows:

sample weight after adhesive impregnation − sample weight after adhesive removal

sample weight after adhesive impregnation − sample weight before adhesive impregnation

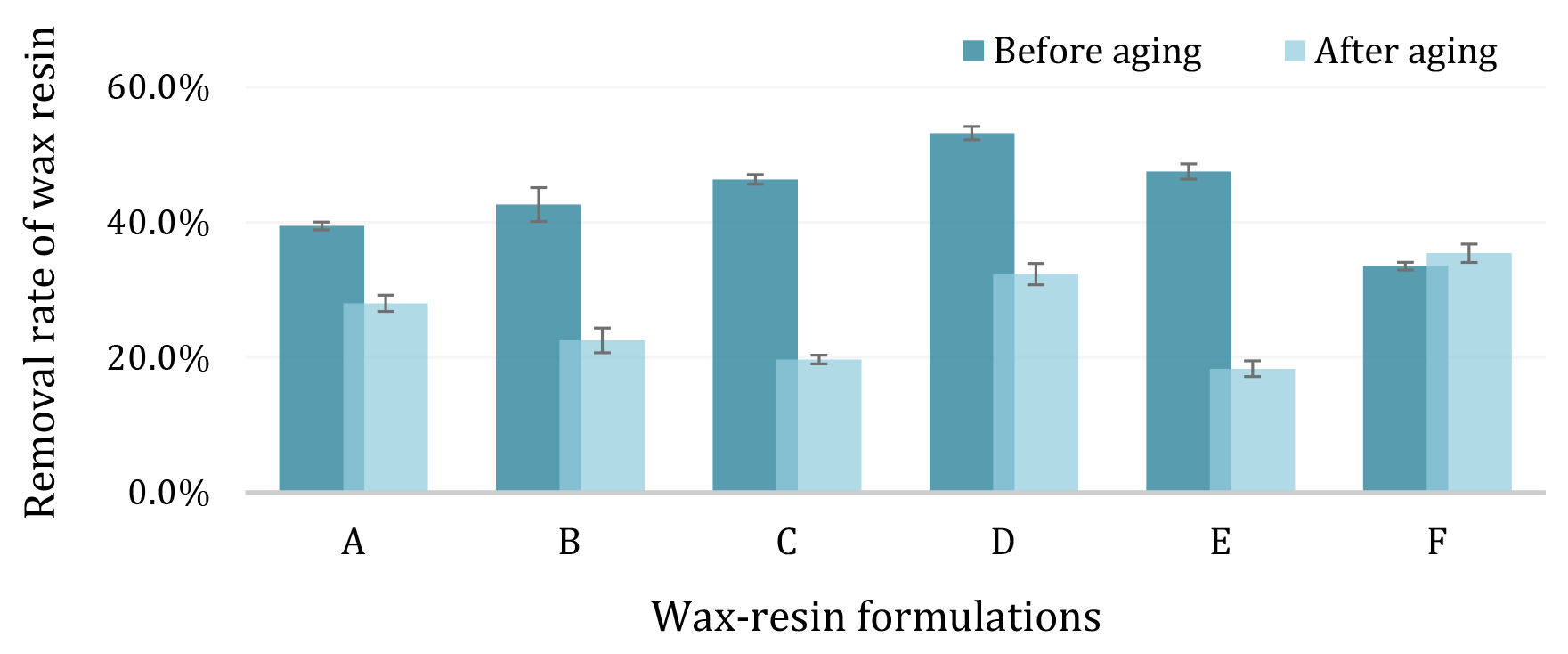

The results are shown in figure 50.2.

Before the artificial aging, it was revealed that the larger the amount of resin in the mixture, the higher the removal rate of wax-resin adhesive. In particular, wax resin D, containing colophony, was removed effectively.

After the artificial aging, the removal rate of wax resin decreased for all the samples except F, which contained no resin. Comparing the samples in terms of the amount of resin, the removal rate of B after aging, with the doubled dammar resin, became smaller than that of A, whereas the opposite results were obtained before aging. It was also revealed that it became difficult to remove C and E, which contained more resins than A; more than 80% of the impregnated wax resin by weight remained on the pieces after removal. As for F, its removal rate didn’t change much after aging. Accordingly, a rough tendency could be summarized as follows: the greater the amount of resin in the wax-resin adhesive, the higher the removal rate of wax resin before aging. Conversely, the more resin there was in the recipe, the less the removal rate would be after aging.

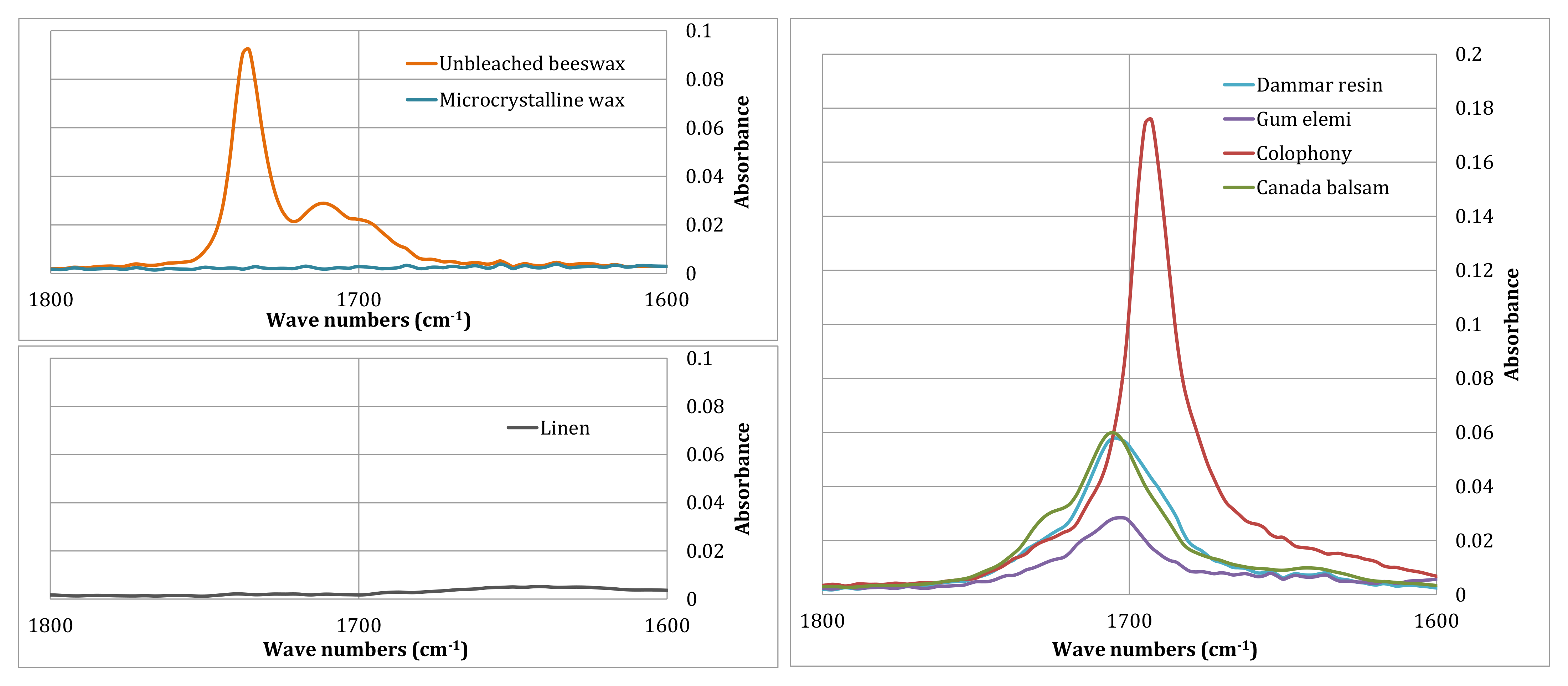

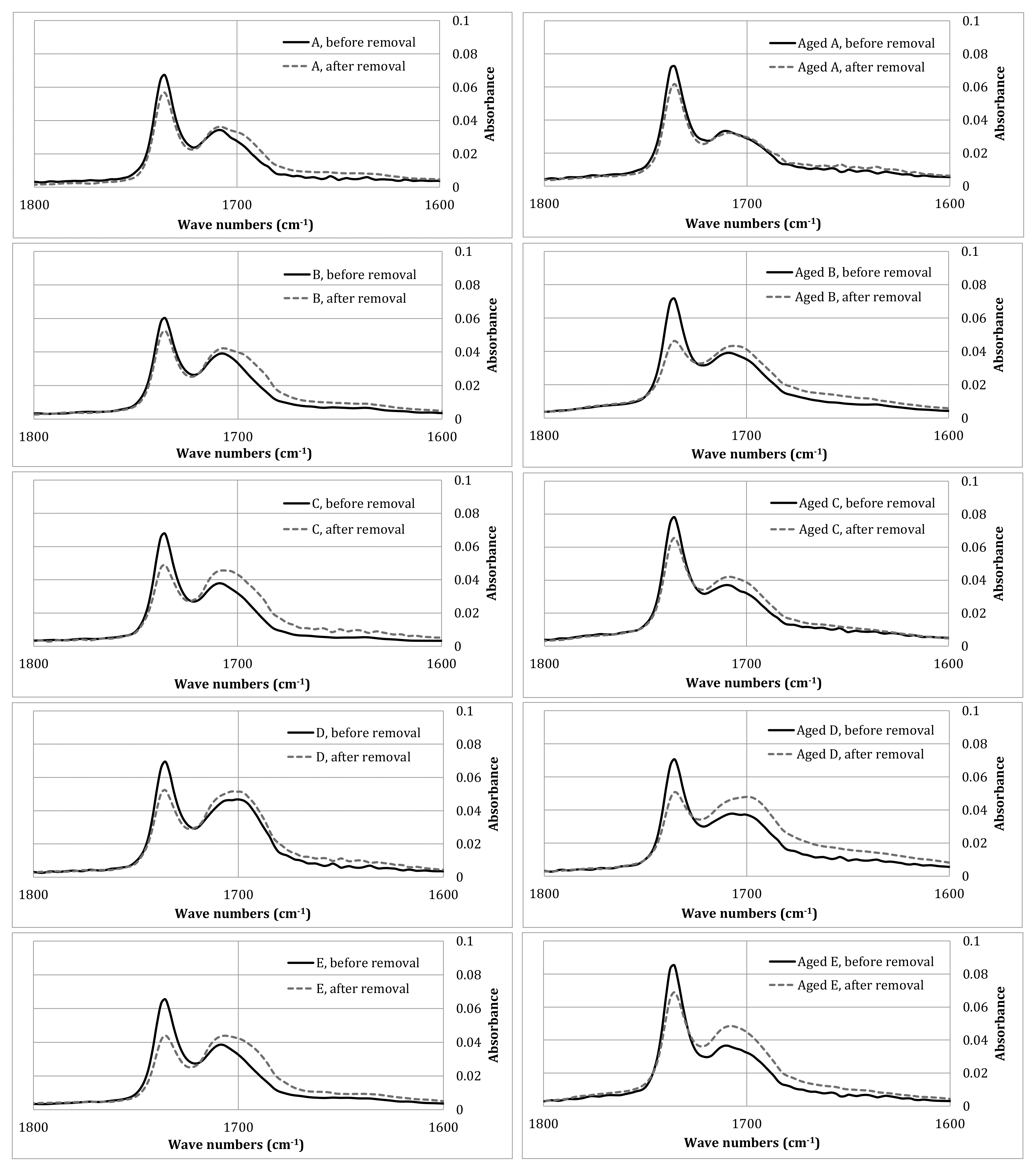

For the next step, what was left on the test pieces after removal was investigated by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra of wax-resin residues both before and after the removal were measured by using a Bruker Alpha FTIR spectrometer with attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. To compare each spectrum, we focused on the range of wave numbers from 1800 to 1600 cm−1. Beeswax has its highest peak at about 1736 cm−1, and resins have peaks at around 1700 cm−1. The spectra of all the components are shown in figure 50.3, and the spectra of mixtures (A–E) are shown in figure 50.4.

As the spectrum of wax resin A before aging shows, its peak intensity became weaker at about 1735 c−1 and a little stronger at about 1710 c−1 by the removal. This implies that the spectrum gradually grows more similar to that of a resin than to that of beeswax. These changes of spectra were common in almost all the mixtures (A–E). These results suggest that beeswax tends to be removed better than resins. The spectra after aging showed changes by the removal similar to those observed before aging.

Discussion of Experimental Results

Through the experiments, it was revealed that the removal rate of wax resin with the method tested varied for each formulation and for the amount and kinds of resins, influenced whether the mixtures could be easily removed. The measurement results of FTIR spectra suggested that the proportions of resins in the residual wax resin on test pieces could increase compared to spectra from before the removal operations. We speculate that resins in the mixtures became oxidized by artificial aging, and the oxidized resins made it difficult to remove the entire mixtures, leaving resin behind on the canvases.

It should be noted that the results reported here were achieved under a specific situation—one method of removal with one solvent—but similar results probably would be achieved using heat for the removal. Melting tests of the Netherlands’ MolArt project (Molecular Aspects of Ageing in Painted Works of Art, 1995–99) showed that only wax was melted out from an aged wax-resin mixture when heating at a certain temperature.3 Aged resins need much higher temperatures and cannot be removed without risk to the paintings. We also need to bear in mind that the remaining resins in the canvas, when not accompanied by wax, can make the paintings even more brittle after the removal operations whether solvents or heat is used for removal.

Conclusion

This poster discussed the introduction of the wax-resin lining method to Japan and how it expanded throughout the country with small modifications. The most common recipes used at that time were deduced. It is likely the recipe we would encounter most often when treating oil paintings lined with wax resin in Japan.

Various recipes of wax-resin adhesive were reconstructed, and some comparisons were made to clarify how various recipes of wax resin behave on removal. The experimental results demonstrated some trends: which recipes of wax-resin adhesive—and which of their components—tend to remain on linen canvas.

In Japan, little study has been done to reconsider old linings of canvas paintings, but it is high time that the findings are well documented and disseminated for present and future generations. We intend to continue research on this matter and hope it will guide conservators and allied professionals to think about how to treat oil paintings lined with wax resin.

Source of Materials for Wax Resin

The following materials were obtained from the same source used by the interviewees or are materials currently available in Japan:

Dammar resin: Holbein Works Ltd., Japan

Gum elemi: Talas, United States

Colophony: Hayashi Chemical LLC, Japan (marketed as Rosin)

Canada balsam: Showa Chemical Industry Co. Ltd., Japan

Beeswax: Yamada Bee Company, Inc., Japan

Microcrystalline wax: Victory White Wax, Baker Hughes, United States

Notes

-

Masako Koyano, personal communication. Koyano, who studied at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, related that people there used the recipe devised by Caroline and Sheldon Keck. The Kecks founded the Conservation Center at the institute, and Sheldon Keck was its director from 1960 to 1965 (Ken Johnson, “Caroline K. Keck, Art Conservator, Dies at 99,” New York Times, January 15, 2008). ↩︎

-

Tsuneyuki Morita, interview by the authors, January 29, 2018. Mitsuhiko Kuroe’s connection to KIK-IRPA was also referred to in this interview. ↩︎

-

Mireille te Marvelde, email message to the authors, February 8, 2020. ↩︎