Component Details

Sugar Caster (88.DH.127.1.a–b)

Lid and vessel, without anchor rod attached to the vessel: H: 14.4 × W: 8.8 × D: 8.1 cm (5 3/4 × 3 1/2 × 3 3/16 in.)

Lid and vessel, with anchor rod: H: 17.2 × W: 8.8 × D: 12.1 cm, 277.23 g (6 3/4 × 3 1/2 × 4 7/8 in., 8 ozt., 18.263 dwt.)1

Lid (88.DH.127.1.a)

1738–39

H: 5.4 × W: 7.2 × D: 7.5 cm, 105.04 g (2 1/8 × 2 7/8 × 3 in., 3 ozt., 7.542 dwt.)

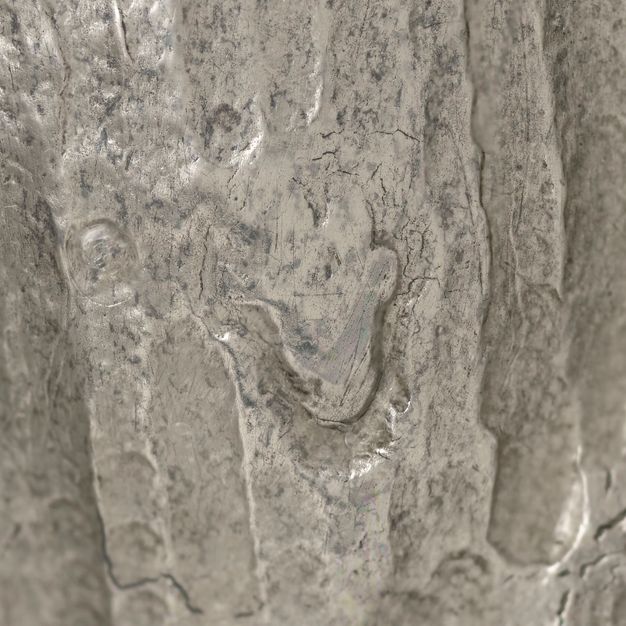

Marks

Struck, on the exterior, with the following stamps: a crowned Y (the Paris warden’s mark used between September 24, 1738, and September 30, 1739) (mark 4.1); and a human foot (the Paris charge mark for [small] works in gold [and silver] used between October 4, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (partially struck) (mark 4.2). Struck, on the exterior of the rim, with the following stamps: a fox head (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and silver used between October 1, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (mark 4.3); a helmet with an open visor (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and old silver used between October 1, 1744, and October 1, 1750, under the fermier Antoine Leschaudel) (mark 4.4), and an assay scratch (mark 4.5).2

Vessel (88.DH.127.1.b)

1738–39

Vessel, without anchor rod: H: 10.8 × W: 6.7 × D: 6.8 cm (4 1/4 × 2 5/8 × 2 3/4 in.)

Vessel, with anchor rod: H: 13.5 × W: 7.2 × D: 9.8 cm, 172.19 g (5 3/8 × 2 9/16 × 3 7/8 in., 5 ozt., 10.720 dwt.)

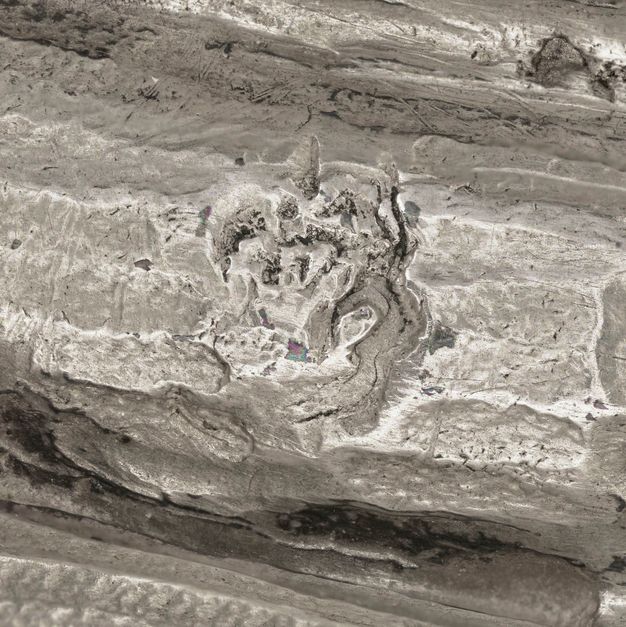

Marks

Struck, on the exterior, with the following stamps: a crowned Y (the Paris warden’s mark used between September 24, 1738, and September 30, 1739) (mark 4.6); and a human foot (the Paris charge mark for [small] works in gold [and silver] used between October 4, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (partially struck) (mark 4.7). Struck, on the interior of the rim, with the following stamps: a fox head (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and silver used between October 1, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (mark 4.8); a helmet with an open visor (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and old silver used between October 1, 1744, and October 1, 1750, under the fermier Antoine Leschaudel) (mark 4.9), and an assay scratch.

Figure and Base (88.DH.127.1.c)

ca. 1739

H: 18.7 × W: 10.6 × D: 12.2 cm (7 3/8 × 4 3/16 × 4 13/16 in.)

Marks

Struck, underneath the base, on the rim, with the following stamp: a crowned C (the tax mark used from March 5, 1745, to February 4, 1749, on all works, old or new, made of copper [cuivre] or a metal alloy containing copper, as imposed by royal edict to defray the debts incurred by the War of Austrian Succession).3

Sugar Caster 88.DH.127.2.a–b

Lid and vessel, without anchor rod: H: 13.7 × W: 7.9 × D: 8.1 cm (5 5/16 × 3 1/8 × 3 3/16 in.)

Lid and vessel, with anchor rod: H: 17.5 × W: 7.9 × D: 13.8 cm, 281.68 g (6 13/16 × 3 1/8 × 5 1/4 in., 9 ozt., 1.124 dwt.)

Lid (88.DH.127.2.a)

1738–39

H: 4.9 × W: 7.7 × D: 8.2 cm, 109.89 g (1 15/16 × 3 × 3 1/4 in., 3 ozt., 10.660 dwt.)

Marks

Struck, on the exterior, with the following stamps: an indecipherable mark, possibly a crowned Y (the Paris warden’s mark used between September 24, 1738, and September 30, 1739); and a human foot (the Paris charge mark for [small] works in gold [and silver] used between October 4, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (partially struck) (mark 4.10). Struck, on the exterior of the rim, with the following stamps: a fox head (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and silver used between October 1, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (mark 4.11); and a helmet with an open visor (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and old silver used between October 1, 1744, and October 1, 1750, under the fermier Antoine Leschaudel) (mark 4.12).

Vessel (88.DH.127.2.b)

1738–39

Vessel, without anchor rod: H: 9 × W: 6.6 × D: 6.7 cm (3 9/16 × 2 9/16 × 2 5/8 in.)

Vessel, with anchor rod: H: 13.3 × W: 6.6 × D: 11.5 cm, 171.76 g (5 3/8 × 2 7/8 × 4 1/2 in., 5 ozt., 10. 444 dwt.)

Marks

Struck, on the exterior, with the following stamps: a crowned Y (the Paris warden’s mark used between September 24, 1738, and September 30, 1739) (mark 4.13); and a human foot (the Paris charge mark for [small] works in gold [and silver] used between October 4, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (partially struck) (mark 4.14). Struck, on the interior of the rim, with the following stamps: a fox head (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and silver used between October 1, 1738, and October 1, 1744, under the fermier Louis Robin) (mark 4.15); and a helmet with an open visor (the Paris discharge mark for small works in gold and old silver used between October 1, 1744, and October 1, 1750, under the fermier Antoine Leschaudel) (mark 4.16).

Figure and Base (88.DH.127.2.c)

ca. 1739

H: 17.8 × W: 12 × D: 13 cm (7 × 4 3/4 × 5 1/8 in.)

Marks

Struck, underneath the base, on the rim, with the following stamp: a crowned C (the tax mark used from March 5, 1745, to February 4, 1749, on all works, old or new, made of copper [cuivre] or a metal alloy containing copper, as imposed by royal edict to defray the debts incurred by the War of Austrian Succession) (mark 4.17).

Description

This pair of sugar casters takes the form of striding laborers, each carrying a large bundle of cut sugarcane on his back (cat. 4.1). The figures and their bases are bronze, while the cane bundles are silver, as are two low-lying plants on each base. Both figures are identical, appearing to have been cast from a common model, though finely chased details render subtle differences in the forelocks of hair on each forehead (cat. 4.2). The rounded bases have been realistically painted in colors appropriate for the muddy earth and low-lying plants of a cane grove. The naturalism of these is contrasted by the metallic surface of the silver and gilded-metal plants on the bases (cat. 4.3). The flesh of the figures has likewise been naturalistically painted brown, their hair black, their lips red, their eyes white with blue irises and black pupils. Their garments and shoes were painted in saturated colors: blue tunics lined with red, red trousers, and black shoes. The style of the tunics, with their applied red-and-gold patterning of stylized chrysanthemums, reflects the prevailing European vision of the Far East, where sugar had been cultivated in South China since 1200–1000 BCE.

Based on the presence of the Paris warden’s date letters and the charge marks, the silver bundles were made in 1738–39 and fitted shortly after to the bronze figures by means of two threaded rods in an aperture at the back of each laborer (cat. 4.4).4 Though securely attached, it is possible to mechanically separate the bundle from its figure (cat. 4.5). Once separated, it becomes apparent that each bundle was made as a freestanding sugar caster in the round, even if the goldsmith’s work would be partially obscured when attached.5 Each one has more than forty-six canes, banded together with horizontal ties at three points along the vertical stalks. The lengths of individual stalks vary; some project higher from the bundle, while others drop lower. Nevertheless, excepting a long protruding threaded rod, each bundle can stand upright, with a slight tilt (cat. 4.6). The bottom of each cane was modeled to suggest its pulpy core, just as those ribbed canes on the bundle’s perimeter were modeled with the characteristic joints of the plant, marking its irregular growth in segments (cat. 4.7). The top opening of each stalk is incongruously adorned, though, with a flattened five-petal flower, suggestive of a cherry or prunus blossom, an unexpected combination perhaps inspired by imported Chinese porcelain brush pots (cat. 4.8).6 Each caster actually has two interlocking parts. The lid consists of the upper third of the cane bundle, the reservoir for sugar the lower two thirds. The uppermost tied-band disguises the catch-latches that keep the lid safely in place when the caster is tilted to sprinkle its fine granular or powdery contents from the openings in the cane tops (cat. 4.9).

Commentary

These painted and varnished exotic figures, carrying silver bundles of harvested sugarcane, evoke the cultivation of cane in far distant tropical climes and the intense labor involved in processing the sweet commodity that was traded around the globe. At first glance, these composite objects appear as sculptures in the round. Their subject of striding laborers, bearing heavy loads upon their backs, falls within a broader artistic genre in which itinerant workers or urban peddlers were realistically portrayed through drawings and engravings or diminutive figures made from, paradoxically, rare and valuable materials such as ivory, precious metal, fragile faience, or porcelain. Since the early 1600s, specialist sculptors and goldsmiths located in central Europe produced such small-scale works, generally about twelve inches in height.7 In France, a subset of the genre was devoted to the iconography of Parisian street peddlers, known by the collective term les cris de Paris, for the distinctive chants the peddlers repeatedly called—or cried out—to advertise their wares.8 The taste for such engravings and figures persisted, and avid collectors still acquired them well into the 1700s. A graphic near parallel to the Getty figures was the contemporary etching showing the coal porter from the print series Cris de Paris of 1737 after François Boucher. In the print, a stepping and stooped male adjusts the ungainly and heavy sack of coal balanced on his back by raising his right arm above his shoulder.9 Simultaneously, the Getty figures were also sober fringe expressions of a newly fashionable French taste of the 1730s and 40s for whimsical chinoiserie bronze characters, finished with a polychromatic paint and varnish surface simulating Chinese or Japanese lacquer, that often accessorized clock cases, inkstands, paperweights, and potpourri vases.10 (For information about a principal Parisian dynasty of such specialist painters and varnishers, see the biography for the Martin Family.)

In theory, the present pair could also function as sugar casters (sucriers à poudre), for the bundles of sugarcane are actually pierced receptacles. Each receptacle consists of two parts—a removable pierced lid and a vessel fixed to the figure’s back. When the lid was twisted off, sugar could have been funneled into the open reservoir inside the hollow bundle. Once the lid was securely back in place, the sugar could have been shaken through the piercings. In practice, however, the weight of the bronze figures would have made this maneuver awkward, perhaps even unmanageable, while seated at a table. A standing servant could have more readily performed the task, but the act would have revealed the painted and varnished yet uneven underside of the bases.11 For these reasons, this pair of composite figures more than likely served an allegorical or symbolic—rather than a functional—purpose, in addition to its aesthetic purpose of delighting the eye and hand of the beholder. This premise is supported, moreover, by two mid-eighteenth-century documents (transcribed below) that described the pieces as figural sculptures, “two China figures” and “two varnished figures,” rather than as sugar casters.

The earliest known document regarding these figures dates from December 20, 1745, when the composite pieces were described in the posthumous inventory of Gabriel Bernard, comte de Rieux, as “two China figures of copper painted by Martin, each carrying silver bundles of Chinese stalks, 60 livres.”12 These figures may well have appealed to the comte de Rieux specifically because they referenced the trade in commodities from the Far East, which was a major source of the Bernard family wealth. Gabriel Bernard was the younger son of the vastly rich financier and banker Samuel Bernard, who served on the Crown’s Council of Commerce and who, together with the mighty financier Antoine Crozat, restructured the French East India Company (Compagnie des Indes orientales) in 1712 under their joint control.13 The codirectors outfitted some twenty successful voyages to the Far East by 1720 before withdrawing from the enterprise, upon its merger with the French West Company (Compagnie d’Occident).14 Hyacinthe Rigaud’s formal portrait of the father, done in 1726, depicts the sitter in a portico, one arm resting on a desk, with a globe turned so that not France but the Indian Ocean is clearly visible, while the other arm gestures to a fleet of trading ships in a busy port.15 The son inherited the father’s Parisian townhouse in 1739 (with the Rigaud portrait) and, evidently, a Sinophile interest, for a catalogue of his library listed many books devoted to the Far East, including Johan Nieuhof’s renowned Ambassades de la Compagnie des Indes orientales de provinces-unies vers l’Empereur de la Chine ou grand Cam de Tartarie of 1665, which twice illustrated sugarcane groves in China, and Luillier-Lagaudiers’s Nouveau voyage aux grandes Indes, avec une instruction pour le commerce des Indes orientales of 1726.16 Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s life-size pastel portrait of 1739–41 shows the son seated in his cabinet, lined with bookcases, with a globe tilted so that the shipping route along the West African coast is visible (fig. 4.1).17

Surviving records of Gabriel Bernard’s accounts show that in the early 1740s he made purchases totaling a staggering amount from dealers in luxury goods (marchands merciers), including François Darnault (14,120 livres in 1741), Martin Hennebert (1,366 livres in 1742), Simon-Henri de la Hoguette (2,444 livres in 1742), Simon-Philippe Poirier (9,194 livres in 1743), Thomas-Joachim Hébert (12,961 livres in 1740–41 and more than 34,000 livres in 1743–45), and “M. Lebrun,” perhaps Pierre or Henri Lebrun (11,122 livres in 1741 and 11,000 livres in 1742–43).18 Any of these could have been the provider of the sugar casters, as well as yet another, Lazare Duvaux, who later cleaned them (as discussed below). Moreover, Hébert and Duvaux frequently commissioned painters in the specialized technique of varnishing wood and bronze surfaces in a manner that evoked Chinese and Japanese lacquer, such as on these figures.19

After the death of Gabriel Bernard on December 13, 1745, the figures seemingly entered into the luxury-goods resale market, which triggered the imposition of a tax on the copper content of the bronze figures and, also, the requisite mark into the underside of each base to certify payment of that tax before February 1749 (see the Marks and Inscriptions section above). The pieces then possibly passed into the possession of Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour, art patroness and official mistress (maîtresse-en-titre) of Louis XV. This transfer is deduced from the records of the preeminent dealer (marchand-bijoutier ordinaire du roi) Lazare Duvaux, who designed, commissioned, and purveyed luxury goods to the court under the special privilege known as marchand suivant la cour.20 The dealer’s daybook for September 9, 1752, records a litany of cleaning and repair work for the marquise de Pompadour, including:

[No.] 1213. – Mme la Marq. de Pompadour … Renew [clean] and restore two varnished figures carrying sugarcane, re-whiten [polish] the said silver canes and flowers, 24 l[ivres].21

Lazare Duvaux often employed the Paris-based Martin family of vernisseurs (specialist painters and varnishers) known “for their beautiful Chinese varnish.”22 No doubt he turned to them again to fulfill this request, for the Martin family had originally painted the pieces, as noted in the Bernard inventory (see above).

Jean Vittet argued persuasively in his article about the contents of the Château de Crécy in the years 1746–57, when owned by the marquise de Pompadour, that Duvaux likely returned the cleaned and polished figures to her Crécy residence or directly to her while attending the king during his sojourn at the Château d’Anet, the country residence of his cousin, the comte d’Eu, from September 9 to 14, 1752. Vittet hypothesized this latter possibility based on other deliveries Duvaux made to the marquise as she moved with the court.23 Whether returned to Crécy or delivered to Anet, the pair (or yet another) could have been among the household contents that passed to the subsequent owner of both châteaux, Louis-Jean-Marie de Bourbon, duc de Penthièvre. In 1757 the duc de Penthièvre purchased the Château de Crécy and all its contents, including the horses, from the marquise and then, in 1775, he inherited the Château d’Anet upon the death of his cousin d’Eu. It is known, moreover, that Penthièvre transferred items (furniture, two large chandeliers, and garden sculpture) from the former to the latter, prior to selling the Château de Crécy to the princesse de Montmorency in 1775.24 Indeed, the Getty figures match a description of one of three such figural pairs at the Château d’Anet in 1781, when still owned by the duc: “two little Indians carrying silver bundles of sugarcane,” “two blacks carrying silver sugarcanes on their backs,” and “two Chinese in gilded-copper having a silver sheaf on the back.”25

It is not certain, though, that the pair belonging to the marquise de Pompadour was the same as that belonging to the duc de Penthièvre. As indicated by the 1781 inventory, the Getty pair was but one among several of the type. A nearly identical pair of varnished silver is now in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (fig. 4.2).26 Neither their figures nor their bases are of bronze. Significantly, the flowers on the bases have pigmented varnish. For this reason, the September 1752 entry of Lazare Duvaux cannot refer to them, for the work order called for “re-whitening” (polishing) the flowers, indicating that the flowers on the pair belonging to the marquise de Pompadour were of unvarnished silver.27 The Wadsworth Atheneum pair is dated to around 1735–36, on account of the Paris warden’s date letter marks and the charge marks they bear.28 They differ from the Getty examples in two ways: (1) the figures’ robes are black with a gilded pattern of ducks, cranes, and flowers, and (2) their bundles of cane are more cylindrical and tightly compact with some sixty-five stalks in each. The joints between the lids and vessels are not disguised. Moreover, it appears unlikely the casters could stand upright if detached from the figures.29 The differences, however, do not extend to the form of the striding figures and their bases, which are almost identical, thereby suggesting a common model for the Wadsworth Atheneum figures, cast in silver around 1735–36, and the Getty figures, cast in bronze around 1739.

Both pairs echo yet another pair made in the 1730s entirely in (unvarnished) silver for Louis-Henri, duc de Bourbon and prince de Condé.30 The exquisitely wrought figures of this third pair portray male and female laborers dressed in feathered skirts, alluding to cane cultivation in the West Indies (fig. 4.3). Each cane stalk of their bundles is more individualized, with a core of greater or lesser thickness, and the irregularly cut tops are not adorned with flower petals. Leafy cane stalks grow up from their bases, and cut cane rings litter the terrain. Michèle Bimbenet-Privat argues the duc de Bourbon’s ownership of these laborers aligns with—and potentially alludes to—his role as an investor and shareholder of the Compagnie d’Occident, an enterprise that participated heavily in the slave trade to support colonial sugar and indigo plantations in the West Indies, and with his authorization in March 1724 to renew and extend the Crown’s Code noir (“Black Code”) to the Louisiana territory.31

None of the silver vessels on these surviving pairs bears a goldsmith’s mark. And only those vessels on the varnished figures bears marks of the Paris guild wardens for workers in precious metal (Le corps des marchands orfèvres-joyailliers de la ville de Paris) for the years of 1735–36 and 1738–39. The absence of goldsmiths’ marks defied guild rules, unless the pieces were made in a privileged enclave that exempted the smith from guild jurisdiction, such as those granted lodgings and workshops in the Crown’s Galeries du Louvre. In the 1730s, four goldsmiths of the king (orfèvres du roi) were lodged there: Claude II Ballin, Nicolas Besnier (succeeded by Jacques III Roëttiers), and Thomas Germain. Gérard Mabille therefore attributed the unvarnished figures of the duc de Bourbon to Claude II Ballin, while Michèle Bimbinet-Privat ascribed them to Jacques III Roëttiers.32 Since the cane bundles on the Getty and Wadsworth Atheneum pairs differ markedly from these, their makers remain anonymous, though surely the smiths worked in association with the Martin family of vernisseurs under the direction of a marchand mercier. The posthumous inventory of Guillaume Martin included, interestingly, “four Chinese figures faux finished, priced eighteen livres.”33

Provenance

Before 1745: Gabriel Bernard, comte de Rieux, French, 1687–1745 (Paris), président à la deuxième chambre des enquêtes du Parlement de Paris (president of the second Chamber of Inquests at the Parliament of Paris);34 before 1752–57: possibly Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, marquise de Pompadour, French, 1721–1764, possibly sold with contents of the Château de Crécy to the duc de Penthièvre; 1757–93: possibly Louis-Jean-Marie de Bourbon, duc de Penthièvre, French, 1725–1793, possibly transferred from the Château de Crécy, or inherited with the contents of the Château d’Anet, in 1775;35 1794: possibly sequestered and sold by the French government, Convention nationale (Château d’Anet), 29 germinal an II (April 19, 1794);36 around 1910(?): Kraemer et Cie, French, active 1875–present (Paris); about 1910: Camille Plantevignes, French, active 1907–16, died 1931;37 ca. 1920–88: private collection (Paris), [offered for sale but withdrawn, Nouveau Drouot, Paris, April 2, 1981, lot 61];38 1988: Jean-Luc Chalmin (Paris and London), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1988.

Exhibition History

Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour: A Love Affair with Style, Dixon Gallery and Gardens (Memphis), March 10–April 15, 1990, and Rosenberg & Stiebel (New York), May 2–April 15, 1990 (no. 36); Madame de Pompadour et les arts, Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (Versailles), February 13–May 19, 2002, Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung (Munich), June 14–September 1, 2002, and National Gallery (London), October 16, 2002–January 12, 2003 (no. 156); Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts, Henry Moore Institute (Leeds), October 2, 2008–January 4, 2009, and J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center (Los Angeles), March 31–July 5, 2009 (no. 11); The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals, Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center (Los Angeles), October 13, 2015–March 13, 2016.

Bibliography

Courajod, Louis, ed. Livre-Journal de Lazare Duvaux, marchand-bijoutier ordinaire du roy 1748–1758, précedé d’une étude sur le goût et sur le commerce des objets d’art au milieu du XVIIIe siècle. 2 vols. Paris: Société des bibliophiles françois, 1873., vol. 2, 135, no. 1213; Meubles et objets d’art, tapis, tapisseries, sale cat., Nouveau Drouot, Paris, April 2, 1981: lot 61, “Deux très rares magots”; “Acquisitions/1989,” with an introduction by John Walsh. The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 17 (1989): 99–166., 142, no. 72; Hunter-Stiebel, Penelope. Louis XV and Madame Pompadour: A Love Affair with Style. Exh. cat. New York: Rosenberg & Stiebel, 1990., 54–55, 93, no. 36, fig. 36; Whitehead, John. The French Interior in the Eighteenth Century. London: Laurence King, 1992., 23, ill.; Bremer-David, Charissa, with Peggy Fogelman, Peter Fusco, and Catherine Hess. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/0892362219.html., 110, no. 184; Sargentson, Carolyn. Merchants and Luxury Markets: The Marchands Merciers of Eighteenth-Century Paris. London: Victoria and Albert Museum; Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996., 176, pl. 18, between 100 and 101; Vittet, Jean. “Le décor du Château de Crécy au temps de la marquise de Pompadour et du duc de Penthièvre: Essai d’identifications nouvelles.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français 2000 (2001): 137–55., 144–45, 153n58, fig. 14; Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78., 72–73, fig. 5a–b, 78nn55–56; Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/089236632X.html., 93–94, no. 190; Salmon, Xavier, ed. Madame de Pompadour et les arts. Exh. cat. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002., 364–65, no. 156 (entry by Gérard Mabille); Bremer-David, Charissa, “Lacquered-Bronze Figures.” In Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts, edited by Martina Droth and Penelope Curtis, 52–53. Exh. cat. Leeds: Henry Moore Foundation; Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009., 52–53, no. 11; Cavalié, Hélène. “Pierre Germain dit le Romain (1703–1783): Une vie à l’ombre des orfèvres du roi.” Ph.D. diss., L’École des chartes, Paris, 2011., vol. 3, 726–29, no. 123; Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle, Florian Doux, Catherine Gougeon, and Philippe Palasi. Orfèvrerie française et européenne de la Renaissance et des temps modernes, XVIe, XVIIIe, XVIIIe siècle: La collection du musée du Louvre. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2022., cat. 190.

Notes

-

The bullion weights include a lacquered layer of clear nitrocellulose coating applied to the silver surface in 2002. Report, March 25, 2002, by Arlen Heginbotham, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

-

This type of assay mark is typical of Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany. Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, conversation with the author, May 9, 2018, on file in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

-

Nocq, Henry. “L’orfèvrerie au dix-huitième siècle: Quelques marques; Le C couronné.” Le figaro artistique, Nouvelle série 31 (April 17, 1924): 2–4.; Verlet, Pierre. “A Note on the ‘Poinçon’ of the Crowned ‘C’.” Apollo 26, no. 151 (July 1937): 22–23.; Verlet, Pierre. Les bronzes dorés français du XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Picard, 1987., 268–71. ↩︎

-

The figures and their bases were separately cast in bronze using a lost-wax technique. The opening on each figure’s back was part of the mold and cast. Two threaded rods secure each bundle of cane to its figure. One rod, soldered to a low external point on the bundle, inserts downward into the opening of the figure’s back. A second rod, projecting outward from the figure’s opening, threads into a ringed hole higher up on the bundle. Technical Report, March 22, 2022, by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

-

The silver bundles of cane were likely made by repoussé. Each was composed from four separately forged sections that were then worked repeatedly on the exterior and interior. The hammering likely created their rough interior texture. Interior pallions of solder were probably applied to repair tears made during raising. The twines wrapping around the cane were likely cast and soldered in place. The petals of the silver flowers on the bronze bases were formed by repoussé. They are mechanically held together by a bronze or brass screw, with a decorative head that imitates the core of the flower. Technical Report, March 22, 2022, by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. For further analytical information, see Appendix: Table 1. ↩︎

-

The unexpected combination of sugarcane and cherry blossoms may have been inspired by imported Chinese porcelain pots intended to hold calligraphy brushes, such as the bamboo and prunus example dating from the reign of the Kangxi Emperor, in the Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet, inv. G 878. See Rimaud, Yohan, Nicolas Surlapierre, Alastair Laing, and Lisa Mucciarelli, eds. Une des provinces du rococo: La Chine rêvée de François Boucher. Exh. cat. Besançon: Musée des beaux-arts et d’archéologie de Besançon, 2019., 100–101, no. 49. ↩︎

-

For example, a figural pair of itinerant poultry sellers, who carry large tubs on their backs, is in the Grüne Gewölbe, Dresden, founded by Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony, in 1723. The figures were carved from wood, painted, and fitted with elaborate silver and gilded-silver accessories. They bear the date letter for 1600 and an unidentified maker’s mark, possibly for a Frankfurt am Main goldsmith. See Sponsel, Jean Louis. Führer durch das Grüne Gewölbe zu Dresden. Dresden: W. und B. v. Baensch, 1921., 198–99, VI 4 and 6. A similar pair is in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, inv. 1917.280–281. See Roth, Linda Horvitz, ed. J. Pierpont Morgan, Collector: European Decorative Arts from the Wadsworth Atheneum. Exh. cat. Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 1987., 98–99, no. 24. ↩︎

-

For an overview, see Isabelle Breuil, “Les cris de Paris,” Le Blog Gallica, La Bibliothèque numérique de la BnF et de ses partenaires, March 10, 2020, http://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/10032020/les-cris-de-paris. ↩︎

-

Etched and engraved by Simon François Ravenet after François Boucher, Charbon Charbon, from Les cris de Paris, Paris, chez Huquier, 1737. La bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal, Paris, inv. EST-267, plate 114, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1522620c/f241.item. See Jean-Richard, Pierrette. L’oeuvre gravé de François Boucher dans la collection Edmond de Rothschild au Musée du Louvre. Musée du Louvre, Inventaire général des gravures: Ecole française, vol. 1. Paris: Éditions des musées nationaux, 1978., 365–66, no. 1517. ↩︎

-

Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78.. ↩︎

-

In contrast, the bases of the analogous pair of cane-carrying laborers, made for the duc de Bourbon, have inserts of silver discs below their bases to cover the rough undersides. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. OA 11749–11750, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010103359 and https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010116150. See notes 30–31 below. Access to these objects was kindly facilitated by Michèle Bimbenet-Privat. ↩︎

-

Listed in the posthumous inventory of Gabriel Bernard, comte de Rieux, as: “No. 144. Deux figures de cuivre peint de Martin portant chacune des hottes de blé de la Chine d’argent, … 60 livres.” Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVIII, 597, December 20, 1745. Alexandre Pradère, fax to Gillian Wilson, November 17, 2000, on file in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum, and cited by Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78., 73, 78n58. ↩︎

-

Clermont-Tonnerre, Élisabeth. Histoire de Samuel Bernard et de ses enfants. Paris: E. Champion, 1914., 155–77; Adams, Julia. “The French Patrimonial Package: System or Anti-System? Law’s Company and the French State.” In The Familial State: Ruling Families and Merchant Capitalism in Early Modern Europe, 166–71. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005., 166–68. ↩︎

-

Spary, Emma C. “From Curious to Consumers.” In Eating the Enlightenment: Food and the Sciences in Paris, 1670–1760, 51–95. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012., 70n32, 71–73. ↩︎

-

Musée national du château be Versailles, inv. MV 7172, http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/?permid=permobj_9f3460a4-a40b-4a43-bed6-292095cbd492. Germain Brice mentioned the portrait hanging in the gallery of the Bernard townhouse in the rue de Notre-Dame des Victoires, “dans un salon en maniere de galerie, [est] le portrait du maître de la maison, de grandeur naturelle peint par Hyacinthe Rigault.” See Brice, Germain. Description de la Ville de Paris et de tout ce qu’elle contient de plus remarquable, Nouvelle édition. Vol. 1. Paris: Chez les Libraires Associés: Le Mercier, Desaint & Saillant, Herissant, Durand, et Le Prieur, 1752., vol. 1, 469–70. ↩︎

-

Much of Gabriel Bernard’s 3,314-volume library was devoted to jurisprudence in support of his career in the Parlement de Paris, but it also covered a broad range of other subject areas, including philosophy, logic, economics, commerce, science, history, medicine, art, rhetoric, poetry, and mythology. Notably, under the heading of Voyages, there was Luillier-Lagaudiers, Nouveau voyage aux grandes Indes, avec une instruction pour le commerce des Indes orientales (Rotterdam: Jean Hofhout, 1726), and under the heading of Histoire de l’Asie was Jean Nieuhoff, Ambassades de la Compagnie des Indes orientales de provinces-unies vers l’Empereur de la Chine ou grand Cam de Tartarie, trad. en François par Jean le Carpentier (Leiden: Jac. De Meurs, 1665). See Catalogue des livres de la bibliothèque de feu Monsieur, Le Président Bernard de Rieux. Paris: Barrois, 1747., 222, no. 2178, and 323, no. 3081. The Nieuhof (alternatively Nieuhoff) volume illustrated sugarcane groves in China. See the volume in La réserve bibliothèque, Musée de l’homme, Paris, inv. Réserve DS 708 N 671 1665, p. 79, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b23000596/f128.item. ↩︎

-

Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, Portrait of Gabriel Bernard de Rieux, 1739–41, J. Paul Getty Museum, inv. 94.PC.39, https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103RK7. Neil Jeffares, “La Tour: Le président de Rieux,” Pastels et Pastellists, issued 2010, updated March 21, 2020, http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/LaTour_Rieux.pdf. ↩︎

-

Alexandre Pradère, “Le fils de Samuel Bernard,” in Pradère, Alexandre. Charles Cressent, sculpteur, ébéniste du Régent. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2003., 68, 69n43. Extant trade cards detail the type of merchandise François Darnault commissioned and sold. Two of his cards advertised that his Paris boutiques, named Au Roy d’Espagne and A La Ville De Versailles, carried “complete toilette services, lacquered in all colors, … and all sorts of other things to furnish apartments” (“Des Toilettes complètes, en vernis de toutes couleurs…& toutes sortes d’autres choses pour meubler les appartemens”). See his trade cards on a commode and on a mirror frame in the J. Paul Getty Museum, inv. 55.DA.2 and 97.DH.4, https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103SC1 and https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/107TBC. See also Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/089236632X.html., 16–17, no. 29 and 59, no. 115. ↩︎

-

Concerning Hébert, see Sargentson, Carolyn. Merchants and Luxury Markets: The Marchands Merciers of Eighteenth-Century Paris. London: Victoria and Albert Museum; Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996., 23–26, 87–90, 154–55, and Pradère, Alexandre. Charles Cressent, sculpteur, ébéniste du Régent. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2003., 62, 63n19. ↩︎

-

Courajod, Louis, ed. Livre-Journal de Lazare Duvaux, marchand-bijoutier ordinaire du roy 1748–1758, précedé d’une étude sur le goût et sur le commerce des objets d’art au milieu du XVIIIe siècle. 2 vols. Paris: Société des bibliophiles françois, 1873., vol. 1, lxxvii. ↩︎

-

“[No.] 1213. – Mme la Marq. de Pompadour … Remis à neuf & rétabli deux figures vernies portant des cannes de sucre, fait reblanchir lesdites cannes d’argent & fleurs, 24 l[ivres].” Courajod, Louis, ed. Livre-Journal de Lazare Duvaux, marchand-bijoutier ordinaire du roy 1748–1758, précedé d’une étude sur le goût et sur le commerce des objets d’art au milieu du XVIIIe siècle. 2 vols. Paris: Société des bibliophiles françois, 1873., vol. 2, 135, no. 1213. See also Gérard Mabille, “Deux sucriers à poudre,” in Salmon, Xavier, ed. Madame de Pompadour et les arts. Exh. cat. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002., 364–65, no. 156. ↩︎

-

“La manufacture royale de MM. Martin, pour les beaux vernis de la Chine,” from L’esprit du commerce (1748), as quoted in Courajod, Louis, ed. Livre-Journal de Lazare Duvaux, marchand-bijoutier ordinaire du roy 1748–1758, précedé d’une étude sur le goût et sur le commerce des objets d’art au milieu du XVIIIe siècle. 2 vols. Paris: Société des bibliophiles françois, 1873., vol. 1, cxxiii–ccxxix. ↩︎

-

Vittet, Jean. “Le décor du Château de Crécy au temps de la marquise de Pompadour et du duc de Penthièvre: Essai d’identifications nouvelles.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français 2000 (2001): 137–55., 144–45, 153n58, fig. 14. ↩︎

-

Vittet, Jean. “Le décor du Château de Crécy au temps de la marquise de Pompadour et du duc de Penthièvre: Essai d’identifications nouvelles.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français 2000 (2001): 137–55., 150–51, 154nn81–83, fig. 21. ↩︎

-

See Vittet, Jean. “Le décor du Château de Crécy au temps de la marquise de Pompadour et du duc de Penthièvre: Essai d’identifications nouvelles.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français 2000 (2001): 137–55., 137–38, 145, 152nn20–22, for a summary of the inventory: “Inventaire général des meubles du château d’Anet tels qu’ils se sont trouvés exister le vingt cinq aoust mil sept [cent] quatre vingt un, lesquels le S. Vibert concierge dudit château s’oblige de représenter toute fois qu’il en sera requis … [page 5]: Salon de glaces … sur la cheminée 2 petits Indiens portants des fagots de cannes de sucre en argent; [page 101]; Conciergerie du château … deux nègres portant sur leur dos des cannes à sucre en argent; [page 105]: Cuivre argenté et doré … 2 Chinois en cuivre doré ayant une gerbe en argent sur le dos.” (Vittet consulted the typed version of the August 25, 1781, inventory conserved in Anet, Bibliothèque de la Société des amis d’Anet, collection Désiré Roussel.) The description of the last figural pair was repeated in a document signed by “Dagomet,” concerning the sequestered goods sold from the Château d’Anet in April 1794: “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, Impartialité, le vingt neuf germinal an second [18 avril 1794] de la République française une et indivisible, moy commissaire soussigné ayant été nommé du sein de l’administration du directoire du district révolutionnaire de Dreux par arrêté datté le 26 du même mois à l’effet de surveiller la vente des meubles et effets appartenant ci-devant à la veuve Orléans déportée dans sa maison d’Anet et actuellement à la République … Etat des vase en porcelainne précieux garnis en argent dans lequel est aussi plusieurs figures étant aussi garnis d’argent lesquels jé envoyés à l’administration du district … deux figures représentant des Chinois en cuivre peint ayant chacun une gerbe d’argent sur le dos” (“Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, Impartiality, twenty-nine germinal second year [18 April 1794] of the French Republic one and indivisible, me [the] undersigned commissioner, having been appointed from within the administration of the directory of the revolutionary district of Dreux by decree dated the 26th of the same month for the purpose of supervising the sale of the furniture and effects belonging above to the widow Orléans deported to her house in Anet and currently to the Republic … State of the precious porcelain vases garnished in silver in which is also several figures being also garnished with silver which I sent to the administration of the district … two figures representing Chinese in painted copper each having a sheaf of silver on their backs,” author’s translation). Chartres, Archives départementales d’Eure-et-Loir, Q 436 III. Information kindly provided by Jean Vittet.

Though located in different parts of the Château d’Anet in 1781, these pairs, Vittet argues, are an allegorical evocation of the Four Parts of the World. He identified the second pair in this list as that now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. OA 11749–11750, formerly in the collection of Louis-Henri, duc de Bourbon. See notes 11 and 30. Pierre Verlet was the first scholar to publish the pair described as “2 petits indiens portant des fagots de cannes à sucre” in the 1781 inventory of the Château d’Anet. Verlet, Pierre. “Louis XV et les grands services d’orfèvrerie parisienne de son temps.” Panthéon (April-May-June 1977): 131–42., 139n10. ↩︎

-

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, inv. 1917.288–289. See Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78., 72–73, 78n56. ↩︎

-

An observation first made in 2003 by Alida de Araujo Bowley, then a student of Professor Sarah R. Cohen at the University at Albany, State University of New York. Sarah R. Cohen, letter to Gillian Wilson, December 2, 2003, on file in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. See the related collaborative article coauthored by Sarah R. Cohen, “Removing the Raw, Commodity Chains in the Global Eighteenth Century,” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, forthcoming. ↩︎

-

Linda Horvitz Roth, then associate curator at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, letters to Gillian Wilson, June 26, 1991, and July 7, 1992, on file in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. See also Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78., 72–73, 78n57. ↩︎

-

Linda Horvitz Roth, email message to author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎

-

The pieces bear traces of the duc’s engraved coat of arms, and they were listed in his posthumous inventory as “two sugar casters, two figures of Moors laden with sugarcanes, of white silver” (“deux sucriers, deux figures de Maures chargé de cannes à sucre d’argent blanc”). Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, XCII, 504, February 17, 1740, as transcribed by Mabille, Gérard. “Deux sucriers à poudre.” In Musée du Louvre: Nouvelles acquisitions du département des Objets d’art 1990–1994, 163–65, no. 61. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1995., 164, no. 61. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. OA 11749–11750, see note 25 above. Apparently, a few more pairs entirely of silver are known through period inventories, yet their precise appearance can only be conjectured. And another pair with small children belonged to Madame de Beringhen, then the marquise de Vassé. See Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78., 73, 78n60. Hélène Cavalié found documentary evidence that the goldsmith Jacques III Roëttiers made a pair of lidded sugar bowls on stands in gold for Louis XV in 1757–64. They bore low-relief panels depicting laborers harvesting sugarcane. See Cavalié, Hélène. “Pierre Germain dit le Romain (1703–1783): Une vie à l’ombre des orfèvres du roi.” Ph.D. diss., L’École des chartes, Paris, 2011., vol. 3, 726–29, no. 123, “1757–1764, deux sucriers d’or de Louis XV.” ↩︎

-

Durand, Jannic, Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, and Frédéric Dassas, eds. Décors, mobilier et objets d’art du Musée du Louvre, de Louis XIV à Marie-Antoinette. Paris: Louvre éditions; Somogy éditions d’art, 2014., 334–35, no. 129. On the Compagnie d’Occident, see Harsin, Paul. “La création de la Compagnie d’Occident (1717): Contribution à l’histoire du système de Law.” Revue d’histoire économique et sociale 34, no. 1 (1956): 7–42., especially 21–22. ↩︎

-

Gérard Mabille ruled out an attribution for the duc de Bourbon pair to either Nicolas Besnier (who spent much of his time in Beauvais after assuming the codirectorship of the royal tapestry manufactory there in 1734) or Thomas Germain. See Mabille, Gérard. “Deux sucriers à poudre.” In Musée du Louvre: Nouvelles acquisitions du département des Objets d’art 1990–1994, 163–65, no. 61. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1995., 164, no. 61. ↩︎

-

“Quatre figures chinoises en faux, prisées dix-huit livres pièces.” Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, CXXI, 345, August 18, 1749. See Wolvesperges, Thibaut. “A propos d’une pendule aux magots en vernis Martin du Musée du Louvre provenant de la collection Grog-Carven.” Revue du Louvre: La revue des musées de France 4 (October 2001): 66–78., 68, 77n11 (where the citation is misnumbered as Minutier central, CXXI, 343), and Forray-Carlier, Anne. “‘L’engouement pour le vernis Martin: Décor intérieur et ameublement.” In Les secrets de la laque française: Le vernis Martin, edited by Anne Forray-Carlier and Monika Kopplin, 71–77. Exh. cat. Paris: Les arts décoratifs; Münster: Museum für Lackkunst, 2014., 75n53. See also Sonenscher, Michael. Work and Wages: Natural Law, Politics, and the Eighteenth-Century French Trades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989., 225–27, especially 226n48. ↩︎

-

The sugar casters are described in his posthumous inventory as “two China figures of copper painted by Martin, each carrying silver bundles of wheat, 60 livres.” Paris, Archives nationales de France, Minutier central, LXXXVIII, 597, December 20, 1745. See note 12 above. ↩︎

-

Possibly the figures described in the August 25, 1781, inventory of the Château d’Anet as “Cuivre argenté et doré … 2 Chinois en cuivre doré ayant une gerbe en argent sur le dos” (“Silvered and gilded copper … 2 Chinese in gilded-copper having a silver sheaf on the back,” author’s translation). Anet, Bibliothèque de la Société des amis d’Anet, Collection Désiré Roussel, Inventaire général des meubles du château d’Anet tels qu’ils se sont trouvés exister le vingt cinq aoust mil sept [cent] quatre vingt un…. See also Vittet, Jean. “Le décor du Château de Crécy au temps de la marquise de Pompadour et du duc de Penthièvre: Essai d’identifications nouvelles.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français 2000 (2001): 137–55., 144–45, 153n58, and note 25 above. ↩︎

-

Possibly the figures described in revolutionary documents as “deux figures représentant des Chinois en cuivre peint ayant chacun une gerbe d’argent sur le dos” (“two figures representing Chinese in painted copper, each one having a silver sheaf on the back,” author’s translation). Chartres, Archives départementales d’Eure-et-Loir, Q 436 III, 29 germinal an II, April 18, 1974. See Vittet, Jean. “Le décor du Château de Crécy au temps de la marquise de Pompadour et du duc de Penthièvre: Essai d’identifications nouvelles.” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français 2000 (2001): 137–55., 145, 152nn20–22. ↩︎

-

Handwritten note, March 6, 2006, by Gillian Wilson, the curator who acquired these sugar casters for the museum in 1988, on file in the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. The death of Camille Plantevignes was published in Le Journal (Paris), October 25, 1931, 2, “Carnet mondain, Nécrologie.” ↩︎

-

Meubles et objets d’art, tapis, tapisseries, sale cat., Nouveau Drouot, Paris, April 2, 1981: lot 61, “Deux très rares magots,” ill. ↩︎