Component Details

Lid (71.DG.77.a)

H: 6.8 × Diam: 18.8 cm, 355.27 g (2 11/16 × 7 3/8 in., 11 ozt., 8.443 dwt.)

Marks

Struck, underneath, near the center, with the following stamps: a partially struck unidentified mark with a crowned fleur-de-lys (a maker’s mark) (mark 2.1); a crowned L (the Paris warden’s mark used between August 13, 1727, and August 12, 1728) (mark 2.2); and a partially struck A with a crown at its side (the Paris charge mark for works of silver, used between December 1, 1726, and October 15, 1732, under the fermiers Jacques Cottin and Louis Gervais) (mark 2.2). Struck with the following stamps: a fleur-de-lys within a pomegranate (the Paris discharge mark for silver vessels, flat and assembled, used between December 1, 1726, and October 15, 1732, under the fermiers Jacques Cottin and Louis Gervais), on the exterior of the rim flange (mark 2.3); and thrice with a boar head (the “restricted warranty” of 800 parts per thousand, or 80 percent, minimum silver standard used in Paris exclusively from May 10, 1838) on the knob, underneath the rim, and on the exterior of the rim flange (mark 2.4).

Inscriptions

The underside of the lid has a paper tag, fixed with red wax, and numbered “1[8]3” (inscription 2.1).

![Close-up of a yellowed tag with the numbers 1[8]3 stained red by the wax adhesive.](/publications/french-silver/iiif/inscription-2-1/inscription-2-1/static-inline-figure-image.jpg)

Bowl (71.DG.77.b)

H: 4.5 × W: 29.8 × D: 18.3 cm, 383.88 g (1 3/4 × 11 3/4 × 7 3/16 in., 12 ozt., 6.840 dwt.)

Marks

Struck, on the exterior, at the top edge, with the following stamps: the maker’s mark consisting of the initials “L.C.” flanking a rose and two grains, below a crowned fleur-de-lys; a partially struck mark (probably the maker’s mark) (mark 2.5); a crowned L (the Paris warden’s mark used between August 13, 1727, and August 12, 1728) (mark 2.5); an A with a crown at its side (the Paris charge mark for works of silver used between December 1, 1726, and October 15, 1732, under the fermiers Jacques Cottin and Louis Gervais) (mark 2.5); and a fleur-de-lys within a pomegranate (the Paris discharge mark for silver vessels, flat and assembled, used between December 1, 1726, and October 15, 1732, under the fermiers Jacques Cottin and Louis Gervais) (mark 2.6). Struck, in the locations given below, with the following stamps: twice the maker’s mark consisting of the initials “L.C.” flanking a rose and two grains, below a crowned fleur-de-lys, once on the face of each handle (mark 2.7); a tulip (the Aix-en-Provence discharge mark for works of gold and small works of silver used from 1781 to 1789), on the face of one handle (mark 2.8); and thrice with a boar head (the “restricted warranty” of .800 minimum silver standard used in Paris exclusively from May 10, 1838), once on the face of each handle and once on the exterior, near the top edge (mark 2.9).

Armorials

The exterior of the bowl is engraved with the coat of arms, surmounted by a count’s coronet, of the Moulinet d’Hardemare family from the Île-de-France (armorial 2.1).

Description

This gilded-silver vessel is a two-handled lidded bowl. The shallow, slightly curving circular bowl is fitted with two flat handles (called “ears”) that project from opposite sides of the rim. Each flat handle is a lyre shape, cast in relief with an inner band enclosing acanthus leaf scrolls and buds, an open bracket, and a roundel with a bust in profile. One profile is female and the other male (cats. 2.1 and 2.2). The bowl is unadorned except for the engraved coat of arms, which was a later embellishment over an effaced, and possibly wider, earlier armorial.1

The two-stepped circular lid has a slightly overhanging lip with guilloche rim. The dome-shaped upper step is chased and engraved with radiating lambrequin spirals. The lower step is chased and engraved with a ring of alternating ornamental forms: a splayed leafy scroll above strap work enclosing a lappet delineated with a diaper pattern followed by a palmette above two C-scrolls encircling a field of the same diaper pattern. The spool-shaped knob has a flat top set with a low-relief, left-facing female profile (cat. 2.3).2 A veil cascades from the braids at the top of her head to her shoulders (cat. 2.4).

Commentary

This form of vessel (écuelle, in French) derived from a seventeenth-century type of shallow bowl, fitted with one flat handle (called an “ear”). In England, this type of vessel went by the term “porringer”—a term that is sometimes still applied to this form—though the traditional contents were broth based in the French-speaking world and gruel based in the English.3 The vessels were for a solitary individual’s use or for a couple’s use, at most. They were not produced in sets for group dining. Indeed, they were often a component of a personal toilette service or traveling equipage.4 Their presence in the toilette service reflected the custom of consuming a fortifying bouillon or beef tea in the morning. The German name for such a bowl, Wöchnerinnenschüssel (maternity bowl), and the Italian, tazza da puerpera (cup for a new mother), testify to this health-conscious practice.5

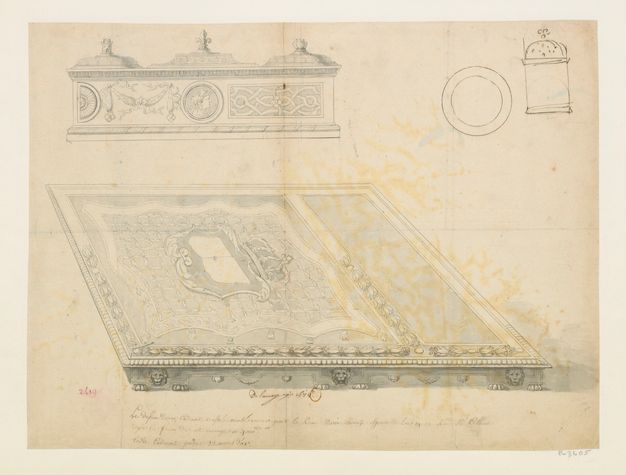

By the 1680s in France, the basic form had evolved into a two-handled lidded bowl, and it remained unchanged throughout the eighteenth century (cat. 2.5). From about 1710 to about 1740, though, subtle stylistic updates can be observed in the flat-chased and engraved ornament on the lids and in the evolving shape of the handles. Popular patterns for ornament and handle shapes disseminated through the engraving titled Ornements pour écuelles by Masson in Nouveaux Desseins pour graver sur l’orfèvrerie, published by Jean Mariette in the early 1700s (fig. 2.1).6 The shape of the bowl and handles of the Getty écuelle is consistent with Masson’s designs, in keeping with a taste that prevailed more than thirty years. The lid, with its chased and engraved bands, also shows the influence of Masson’s proposal.

The motifs of profile heads derive from a different source, however. They were inspired, ultimately, by a medallion in the design proposal for the gold caddinet of Marie Thérèse d’Autriche, queen of France. A caddinet is a ceremonial stand for cutlery, bread, salt, and napkin that was used while dining in public. The profile bust medallion in the drawing for the caddinet presented a classicized woman wearing a diadem, facing right (fig. 2.2).7 The design and box were executed in 1678 by Nicolas Delaunay, one of the goldsmiths to the king (orfèvres du roi), whose powerful influence permeated the craft in Paris.8 In addition to this role, he was director of the royal mint for medals at the Louvre from 1696.9 He was, himself, a collector of tokens (jetons) portraying the kings of France from the legendary Pharamond to Louis XIV.10

Nicolas Delaunay incorporated profile medallions in other works he created after the 1678 caddinet, thus establishing a long trend in silver plate in Paris and beyond.11 His apprentice’s theft of box lids with male and female heads from the workshop in 1695 testifies to the enduring material value and aesthetic merits of this successful design motif.12 Similar roundels of classicizing profile busts soon adorned the handles of écuelle bowls and their spool-shaped knobs (fig. 2.3).13 In principle, this practice refreshed a Germanic Renaissance antiquarian taste for incorporating casts of ancient Greek and Roman coins into newly made silver cups and tankards. While evoking ancient Roman coin types, the seventeenth-century profile busts also reflected contemporary French tokens (jetons) and medals. The elaborately braided hairstyle of the right-facing female bust on one handle of the Getty écuelle, for instance, echoes that seen in antique coins of Faustina the Elder, wife of Emperor Antonius Pius, and approximates that of Marie Adélaïde de Savoie, duchesse de Bourgogne and future dauphine de France, as minted on a silver token of 1700 (see cat. 2.1).14 There were few ancient coins with left-facing profiles, as oriented on the knob of the écuelle, but this orientation was not avoided in the 1700s (see cat. 2.4).15 Considering the features of that female profile, especially the veil that descends from the crown of the head, it is vaguely reminiscent of Anne d’Autriche, queen of France and then regent for the young Louis XIV.16 It seems, therefore, Parisian artisans freely borrowed such profile busts from a variety of sources near at hand, such as contemporary tokens, medals, and vessels, that they then rendered in a classicizing manner.

The taste for these profile medallions burgeoned again in the mid-nineteenth century, as documented by the private manuscript catalogue of the personal collection of Jérôme Pichon, the celebrated connoisseur of old silver. Regarding one écuelle in his possession in 1855, he wrote:

150. An écuelle

with lidwhose ear shape handles represent the head of a bearded philosopher surrounded by ornaments marked GC or GG countermarked R, mark of Hubert Louvet, its lid of a very beautiful shape covered with engraved ornament of the best kind and surmounted by a large round knob on which is chased a portrait of a woman styled a little like Anne d’Autriche. Same mark except the countermark is S. Another mark representing [incomplete] [… purchased from] Delamarre Tuesday September 22, 1855 90 [francs] for the fashioning [making or repairing].17

Given the sheer number of extant knobs with the same female profile as portrayed on the Getty example, one surmises Jérôme Pichon was describing the same model.18 It is intriguing that he associated the classicizing profile with Anne d’Autriche. Recent research by Michèle Bimbenet-Privat has revealed that Pichon was responsible for making new écuelle lids to match authentic écuelle bowls. He had at least one new lid engraved in the fashion of Masson’s design of around 1700 and fitted with a spool-shaped knob bearing the same female profile roundel.19 Was the knob on his own écuelle the source for the reproductions? His activities tie into an écuelle revival in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, when Parisian workshops, such as Maison Duponchel and Maison Puiforcat, produced versions in the historicistic baroque manner of the so-called Louis XIV style.20

Since the écuelle revival in the second half of the nineteenth century generated not only historicistic reproductions but also deceptive forgeries, the Getty bowl and lid were analytically studied to understand their material properties, physical appearances, and irregular marks. Though both bowl and lid bear the same Paris warden’s and charge marks for 1727–28, it is apparent the two were made by different goldsmiths since the partially struck and indistinct, overpolished maker’s mark on the lid does not match those on the bowl (compare mark 2.1 and mark 2.7). In general, the marks on the plain surfaces of the bowl and on the rim of the lid are all worn from overpolishing and cleaning; they are shallower and have lost definition.

Moreover, despite both parts having been made within the same span of years from similar silver alloys, there are noticeable differences in the appearance of their respective discharge and warranty marks that require explanation (compare mark 2.3 to mark 2.6 and mark 2.4 to mark 2.9).21 Not only do the two pomegranates of the discharge and the two boar heads of the warranty marks vary in their shallow-relief delineation but the contours of their perimeters differ as well, indicating they were likely struck by different punches. The lid’s and the body’s individual histories, apart from each other, could account for these discrepancies. For instance, the two pieces may have been struck with their respective discharge marks on different dates within the six-year span of the presiding fermiers’ term of office between 1726 and 1732. The same is true for the multiple and distinctive warranty stamps; the two struck on the lid and its knob are of consistent form, as are each of the three on the bowl and on each “ear” handle. It is also worthy to recall, per the presence of yet another discharge mark (see mark 2.8), that the bowl alone passed through the southern city of Aix-en-Provence at some point between 1781 and 1789.22

Precisely when the two parts, lid and bowl, were united is not clear, but it was certainly before 1923, when they were documented together as a single unit, together with a stand or dish (now lost), in a photograph in the Paris auction catalogue for the Marius Paulme collection (fig. 2.4).23 In that auction catalogue, the object parts were described as being of gilded silver. Based on scientific analysis, it appears the lid and bowl were entirely mercury gilded in the eighteenth century, but their exteriors were later regilded electrolytically at some point after the mid-nineteenth century and before their sale in 1923.24 And it seems their original gilded interiors may have been coated at the time of electroplating to prevent the reaction occurring on those surfaces.25

Since 1923, at least, the bowl has carried the coat of arms of the Moulinet d’Hardemare family (see armorial 2.1).26 It is very unlikely this armorial was engraved on the bowl when it was in the workshop of Louis Cordier because of its inferior quality of execution and because traces remain of an effaced contour from a prior armorial cartouche. In the 1880s, the Moulinet d’Hardemare family owned and restored the Château de Selles-sur-Cher in the Centre-Val de Loire region. This decade coincided with the historicistic baroque revival period for écuelles and may have been the era when the external surfaces of the Getty example were electrolytically regilded and the current family arms were engraved.27

At some point between 1923 and 1971, the stand historically associated with the Getty écuelle went missing and remains untraced.28 The only known image documenting its appearance is the same one from the 1923 auction catalogue of the Marius Paulme collection (see fig. 2.4).29

From 1971 to 2017, the Getty écuelle was mistakenly ascribed to another Parisian goldsmith, Claude Gabriel Dardet (active 1715–29, master 1715).30 The origin of this error was faulty cataloguing published in November 1971, at the time of the second sale of silver from the estate of David David-Weill (who died in 1952) that took place after the death of his widow, Flora David-Weill, in 1970. Confusion arose from the existence of three very similar écuelles. The catalogue entry for the auction of November 24, 1971, conflated information relevant to each, when, in fact, only the Cordier écuelle was included in the sale.31 Through the agent French & Company, the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired the Cordier écuelle (and a dish of later date that was included to serve as its stand) at that sale, and they were shipped to New York in 1971.32 The discrepancy between the catalogue description and the object’s actual maker’s mark went unnoticed, as did the significance of the paper tag, marked with “1[8]3” in ink, that is fixed with red wax to the underside of the lid (see inscription 2.1). Careful review has since concluded the provenance provided in the November 1971 sale catalogue does not apply to the Cordier écuelle.33 The number “183” written on the tag confirms, rather, its proper provenance as having come from the Marius Paulme collection in April 1923.

Provenance

Moulinet d’Hardemare family (Normandy and Île-de-France); before 1923: Marius Paulme, French, 1863–1928 (Paris) [sold with its stand, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, April 18–19, 1923, lot 183, to “M[onsieur] W…”];34 by 1926–52: David David-Weill, French and American, 1871–1952 (Paris), by inheritance to his wife Flora David-Weill; 1952–70: Flora David-Weill, French, 1878–1970 (Paris) [sold after her death, Palais Galliéra, Paris, November 24, 1971, lot 17, to the J. Paul Getty Museum].35

Exhibition History

Exposition d’orfèvrerie française civile du XVIe siècle au début du XIXe, Musée des arts décoratifs (Paris), April 12–May 12, 1926 (no. 20, with Louis Godin named as maker, lent by Monsieur David-Weill); The J. Paul Getty Collection of French Decorative Arts, Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit), October 3, 1972–August 31, 1973 (lent by the J. Paul Getty Museum).

Bibliography

Catalogue des objets d’orfèvrerie ancienne, principalement de “Vieux Paris” du XVIIIe siècle … composant la collection de M. M. P […], sale cat., Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, April 18–19, 1923: 51, lot 183, “Écuelle à bouillon et présentoir, en vermeil”; Exposition d’orfèvrerie française civile du XVIe siècle au début du XIXe. Exh. cat. Paris: Le Musée, 1926., 9, no. 20, lent by Monsieur David-Weill; Collection D. David-Weill (deuxième vente d’orfèvrerie)—Orfèvrerie France XVe au XVIIIe siècle, sale cat., Palais Galliéra, Paris, November 24, 1971: lot 17, “Écuelle et son couvercle en vermeil”; French Silver in the J. Paul Getty Museum, exh. brochure (Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1988), 2, fig. 1; Bremer-David, Charissa, with Peggy Fogelman, Peter Fusco, and Catherine Hess. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/0892362219.html., 112, no. 187; Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/089236632X.html., 96, no. 193; Wilson, Gillian, with Charissa Bremer-David, Jeffrey Weaver, Brian Considine, Arlen Heginbotham, Katrina Posner, and Julie Wolfe. French Furniture and Gilt Bronzes: Baroque and Régence; Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008., 374, fig. 19.

Notes

-

X-radiography by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum, determined that the bowl was hammer raised from silver sheet metal. The “ear” handles were cast and soldered to the exterior of the bowl. X-ray fluorescence revealed that the silver alloy for the handles appears to have a higher percentage of copper than that of the bowl, which is typical for castings. The gilded surfaces have higher levels of gold on the interior of the bowl and on the underside of the handles, which apparently received less vigorous polishing over the years. The gilded surface on the exterior of the bowl has been polished and cleaned repeatedly over time, wearing away the definition of the marks and some areas around the armorial, though the current engraved coat of arms has suffered less abrasion. For further analysis regarding the gilded-silver surfaces, see note 25 below and Appendix: Table 2. Technical Report, November 5, 2021, updated December 3, 2021, by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. X-radiographs were captured at 400 kV, 2 mA, 500 mSec, and 60 inches, with a GE X-radiography system with digital detector array. ↩︎

-

X-radiography by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum, determined that the dome-shaped lid was formed by hammer raising silver sheet metal and by solder joining additional separately cast elements. The guilloche rim was cast and soldered to the perimeter of the circular lid. The density of this rim is comparatively more porous than the raised lid, a characteristic consistent with the casting technique. The female profile disc on the spool shape knob may have been separately cast and soldered in place. The knob itself was hollow cast and soldered to the top center of the lid. A small aperture piercing through the lid’s center may have facilitated the venting of gases created when the knob was attached (see mark 2.2). Alternatively, the aperture may also indicate that a prior knob was originally attached by a threaded rod through this circular hole and that the present knob is a later replacement. Concentric tool marks visible under the lid, which radiate from the center and cross over the maker’s mark (see mark 2.1), were probably caused by later polishing on a lathe. The gilded surfaces have higher levels of gold on the interior than the exterior to the extent that the visible color of the gilding appears different. For further analysis regarding the gilded-silver surfaces, see note 25 below. Technical Report, November 5, 2021, updated December 3, 2021, by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. X-radiographs were captured at 400 kV, 2 mA, 100 mSec, and 60 inches, with a GE X-radiography system with digital detector array. ↩︎

-

Glanville, Philippa. Silver in England. London: Unwin Hyman, 1987., 62; Wees, Beth Carver. English, Irish, and Scottish Silver at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1997., 43. ↩︎

-

The most elite toilette services sometimes contained more than one écuelle. For example, the gilded-silver service assembled around 1743–45 by Augsburg goldsmiths for the Counts of Schenk von Stauffenberg at Schloss Jettingen had two écuelles. The complete set is preserved intact with its original gilt-wood traveling case in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. 2005.364.20a,b and 2005.364.36a,b, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/231564 and https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/231584.

For a gilded-silver traveling equipage, complete with an écuelle and its original traveling case, see the example made by Christian Friedrich Weber and other Augsburg goldsmiths ca. 1750, formerly in the collection of Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, inv. K 200g. Müller, Hannelore. European Silver: The Thyssen Bornemisza Collection. Translated by P. S. Falla and Anna Somers Cocks. New York: Vendome Press, 1986., 240–61, no. 77 and especially 244–45, no. 5; Gold and Silver Treasures from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. Exh. cat. Lugano: Collection Thyssen-Bornemisza; Milan: Electa, 1987., 49, lot 35. ↩︎

-

Schroder, Timothy B. The Art of the European Goldsmith: Silver from the Schroder Collection. New York: American Federation of Arts, 1983., 161–62, no. 64; González-Palacios, Alvar. Luigi Valadier. New York: Frick Collection; London: D. Giles Limited, 2018., 110–11, “A Gilded Écuelle.” ↩︎

-

Fuhring, Peter. “Le second style Louis XIV et la Régence ou la liberté retrouvée.” In Orfèvrerie française: La collection Jourdan-Barry, edited by Peter Fuhring, Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, and Alexis Kugel, vol. 1, 94–98. Paris: J. Kugel, 2005., vol. 1, 94, fig. 1. ↩︎

-

The caddinet no longer survives, though the design proposal is preserved in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, dèpartement Estampes et photographie, RESERVE LE-9 (1)-FOL, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b69370174.item. ↩︎

-

Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle. “Le maître et son élève Claude Ballin et Nicolas Delaunay orfèvres de Louis XIV.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 161, no. 1 (2003): 221–39.. ↩︎

-

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Z1B 98, fol. 296, November 22, 1696. Delaunay took the office of “directeur des balanciers du château du Louvre pour la fabrication des médailles et jetons d’or et d’argent, de bronze et de cuivre, contrôleur et garde de la fabrication des médailles et jetons” (“director of the balance scales at the Louvre castle for the manufacture of medals and tokens of gold and silver, bronze and copper, controller and guard of the manufacture of medals and tokens,” author’s translation) as transcribed in Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle. Les orfèvres et l’orfèvrerie de Paris au XVIIe siècle. Vol. 1, Les hommes. Vol. 2, Les oeuvres. Paris: Éditions des Musées de la ville de Paris, 2002., vol. 1, 312, and Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle. “Le maître et son élève Claude Ballin et Nicolas Delaunay orfèvres de Louis XIV.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 161, no. 1 (2003): 221–39., 236. ↩︎

-

Delaunay gave his collection to Louis XIV in 1715. See Marinèche, Philippe. Collection des rois de France entreprise par monsieur Delaunay, présentée à Louis XIV en 1715. [Orthez]: P. Marinèche, 2011.. Portrait of Goldsmith Nicolas Delaunay and His Family, by Robert Le Vrac Tournières (1704), shows the family in the apartment for the king’s medal cabinet at the Louvre, with Nicolas Delaunay displaying medals he executed portraying the monarch and the dauphin (see fig. 1.6). The portrait is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, inv. 78.2.1, https://mba.caen.fr/oeuvre/portrait-de-lorfevre-nicolas-de-launay-et-de-sa-famille. See also Barker, Emma. “‘No Picture More Charming’: The Family Portrait in Eighteenth-Century France.” Art History 40, no. 3 (2017): 526–53.. ↩︎

-

Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle. “Le maître et son élève Claude Ballin et Nicolas Delaunay orfèvres de Louis XIV.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 161, no. 1 (2003): 221–39., 236. For a representative range of the trend during Nicolas Delaunay’s era, see the illustrated title page of Nouveaux livre d’orfèvrerie by Daniel Marot, ca. 1701–3, and the gilded-silver charger by Paul Crespin of 1727–28, with six medallions of philosopher heads in profile (whose names are engraved on the back of each portrait). Both are in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. 13671:1 and LOAN: GILBERT.717-2008, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1043356/nouveau-livre-dorfeverie-title-page-marot-daniel/ and http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O156506/charger-paul-crespin/. Information courtesy of Tessa Murdoch. Fuhring, Peter. Ornament Prints in the Rijksmuseum II: The Seventeenth Century. Translated by Jennifer Kilian and Katy Kist. Part 1. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum in association with Sound & Vision, 2004., part 1, 250, no. 1440; Schroder, Timothy B. The Gilbert Collection of Gold and Silver. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988., 192–95, no. 47. ↩︎

-

Paris, Archives nationales de France, Z1B 522, September 22, 1695, as recorded in Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle. Les orfèvres et l’orfèvrerie de Paris au XVIIe siècle. Vol. 1, Les hommes. Vol. 2, Les oeuvres. Paris: Éditions des Musées de la ville de Paris, 2002., vol. 1, 312. ↩︎

-

See the silver écuelle of 1712, possibly by Pierre Jarrin, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. 1993.402a–b, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/52615/ecuelle; also the silver example made in 1725–27 by Nicolas Antoine de Saint-Nicolas in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. 48.187.404a, b, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/200366; and the later, coarser one of 1745–46 by Pierre-Henry Chéret at the Petit Palais, Musée des beaux-arts de la ville de Paris, inv. ODUT1452, http://parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/petit-palais/oeuvres/ecuelle-couverte-0. ↩︎

-

The elaborate coiffure of Faustina the Elder was distinctly visible in her profile minted on Roman imperial coins. Information courtesy of Jeffrey Spier. For the silver token of 1700 with the profile portrait bust of Marie Adélaïde de Savoie, see Feuardent, Félix. Jetons et Méreaux depuis Louis IX jusqu’à la fin du Consulat de Bonaparte. Vol. 2. Paris: Rollin et Feuardent, 1907., vol. 2, 341, no. 9728. ↩︎

-

The medal cabinet (médaillier de Lorraine) commissioned by Léopold, duc de Lorraine, contains thirty-nine copper medals made between 1727 and 1731 after the engravings of Ferdinand de Saint-Urbain. Thirty-three of these present double portraits of the ducs de Lorraine and their spouses, the profile of the husband on one side and that of the wife on the other. Many of the profiles, both male and female, look to the left. The female portraits, though meant to be faithful to the historical sitters, are stylistically consistent with the coiffures, jewelry, and dress of the profiles incorporated into Parisian silver dating from the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Musée de Lorraine de Nancy, Palais des ducs de Lorraine, inv. no. D.71.4.8, https://www.musee-lorrain.nancy.fr/en/collections/les--uvres-majeures/medaillier-de-lorraine-65. ↩︎

-

See the tokens from the 1660s showing Anne d’Autriche as regent, wearing her widow’s veil, for example in Feuardent, Félix. Jetons et Méreaux depuis Louis IX jusqu’à la fin du Consulat de Bonaparte. Vol. 1. Paris: Rollin et Feuardent, 1904., vol. 1, 8 and plate VI, nos. 119–23. ↩︎

-

“150. Une écuelle

avec coudont les oreilles représentent une tête de philosophe barbu entourée d’ornemens marquée GC ou GG contremarquée R, poinçon d’Hubert Louvet, son couvercle d’une très belle forme couvert d’ornemens gravés du meilleur genre et surmonté d’un gros bouton rond sur lequel est dans un amati un portrait de femme coiffée un peu dans le genre d’Anne d’Autriche. Même poinçon sauf le commun qui est un S. Autre poinçon représentant [incomplèt] Delamarre mardi 25 septembre 1855 (90 [francs] façon), 258 750.” The handwritten catalogue of Jérôme Pichon is preserved in the Département des objets d’art at the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Information courtesy of Michèle Bimbenet-Privat. ↩︎ -

This profile roundel appears, for example, in several écuelles marked for Pierre Jarrin. The earliest one is dated 1712; it sold at Tajan, Paris, June 14, 1999, lot 42. Louis Favier produced his own variant in 1714–15, and Françoise De Lapierre his version in 1717–18; see Fuhring, Peter, Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, and Alexis Kugel. Orfèvrerie française: La collection Jourdan-Barry. 2 vols. Paris: J. Kugel, 2005., vol. 2, 36, no. 77, and 38–39, no. 84. ↩︎

-

One instance of Pichon’s mastery as a forger is the lid to a gilded-silver écuelle presently in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. OA 9673, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010249246. Its bowl, which bears the Paris warden’s mark “Z” (used under Paul Manis between July 28, 1716, and July 22, 1717), is authentic. However, the lid and the stand, which bears a forged Paris warden’s mark “A” (in use 1717–22), are now considered to be fakes made in Paris after 1878 (Bimbenet-Privat, Michèle, Florian Doux, Catherine Gougeon, and Philippe Palasi. Orfèvrerie française et européenne de la Renaissance et des temps modernes, XVIe, XVIIIe, XVIIIe siècle: La collection du musée du Louvre. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2022., entry OA 9673). Information kindly shared by the Bimbenet-Privat in advance of the Musée du Louvre’s forthcoming catalogue of silver. Previously, the Niarchos/Louvre écuelle was in the collection of the Puiforcat family (offered for sale at Galerie Charpentier, Paris, December 7–8, 1955, lot 82). It, in turn, became a model for modern replicas produced by the Puiforcat firm of goldsmiths. See the pair made around 1900 sold at Sotheby’s, Geneva, May 14, 1990, lot 32. Concerning Puiforcat production, see Puiforcat, [Jean E. or Louis-Victor]. L’orfèvrerie française et étrangère. Tournai: Éditions Garnier Frères, 1981.. The Niarchos/Louvre écuelle was previously catalogued by Gérard Mabille; see Mabille, Gérard, Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, Catherine Gougeon, and Philippe Palasi. La collection Puiforcat: Donation de Stavros S. Niarchos au département des Objets d’art, orfèvrerie du XVIIe au XIXe siècle. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994., 50, no 17. ↩︎

-

For an example made by Maison Duponchel, see Catalogue des objets d’art et d’ameublement de l’Orient et l’Occident composant l’importante collection de feu M. Marquis, sale cat., Hôtel Drouot, Paris, February 10–18, 1890: lot 111 (not illustrated). Regarding Maison Puiforcat, see note 19 above. ↩︎

-

The bowl of the Getty écuelle and its lid are made of similar alloy, with the exception that the alloy for the bowl has more lead than that for the lid. This is consistent with the manufacture of the pieces from two slightly different alloys. X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy Report for the lidded bowl (écuelle), 71.DG.77, January 4, 2019, by Jessica Chasen and Arlen Heginbotham, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. Julie Wolfe noted that other trace elements were registered in such small quantities that they could not be further analyzed by X-ray fluorescence under the gilded-silver surface. Technical Report, November 5, 2021, updated December 3, 2021, by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

-

These observations benefitted from discussions with Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

-

Catalogue des objets d’orfèvrerie ancienne, principalement de “Vieux Paris” du XVIIIe siècle … composant la collection de M. M. P […], sale cat., Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, April 18–19, 1923: 51, lot 183, “Broth bowl with stand, gilded silver,” ill.: “Écuelle à bouillon et présentoir, en vermeil. L’écuelle est munie de ses oreilles ornées d’un médaillon à buste d’homme ou de femme sur arabesque, dans un cartel contourné, à feuillage et volutes avec coquille. Armoiries gravées. Le couvercle, surmonté d’un bouton mouluré avec médaille, est, ainsi que le présentoir, à bord contourné, gravé d’arabesques, fleurons, palmettes, quadrillés, etc. Bord è entrelacs. Vieux Paris. Commencement de l’époque Louis XV. Diam. du présentoir, 255 millim. Poids, 1540 gr. P[oinçon]. de Ch. de Charles Cordier (1722–1727). P[oinçon]. de Contr[olleur]. de Paris: L (1727–1728). P[oinçon]. du M[aître]. O[rfèvre]. parisien aux initiales L C; different: un trèfle.” (“Lot 183. Broth bowl with stand, gilded silver. The bowl has ear shape handles adorned with a medallion of a male or female bust above an arabesque, within a rounded cartel, with foliage and scrolls with a shell. Engraved armorials. The lid, surmounted by a molded knob with a medal, is, like the stand, elaborately banded, engraved with arabesques, florets, palmettes, checkered-squares, etc. Edged with a guilloche. Old Paris [silver]. Beginning of the Louis XV period. Diam. of the stand, 255 millim. Weight, 1540 gr. Charge Mark of Charles Cordier (1722–1727). Paris Warden’s Mark: L (1727–1728). Parisian Master Goldsmith’s Mark with the initials L C; different: a trefoil,” author’s translation). ↩︎

-

Electroplating is a process, developed in the first half of the nineteenth century, that submerges the object to be plated (for example, the Getty’s mercury-gilded silver écuelle) into a bath of conductive electrolyte solution containing a piece of chosen plating metal (for example, gold). When the bath is electrified, plating metal ions transfer to the surface of the object. In general, the process has good adhesion and is able to consistently produce a very thin, continuous plating layer. Consequently, it has become the most commercially used technique for plating from the mid-nineteenth century until today. Susan La Niece et al., “Gilding and Plating,” a definition from the CAST:ING Project’s Guidelines for the Technical Study of Cast Bronze Sculpture. See CAST:ING (website), accessed April 4, 2022, http://www.cast-ing.org/. ↩︎

-

X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy Report for the lidded bowl (écuelle), 71.DG.77, January 4, 2019, by Jessica Chasen and Arlen Heginbotham, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. The report registered the presence of mercury in the gilded surface of this object, which is generally indicative of the amalgamation fire-gilding technique used during the eighteenth century. The report’s authors, though, qualified its presence: “While the presence of mercury can generally be considered indicative of fire gilding, it is possible that at lower levels it may relate to pre-treatment of the surface with mercury salts prior to electroplating, with no history of mercury gilding.” Julie Wolfe determined, however, that there could be more than one cause for the elemental differences registered in the alloy and in the chromatic differences of the gilded-silver surfaces. The documented history of the museum’s localized campaigns to treat tarnish, when polishing compounds and acidified (sulfuric) thiourea solutions were used, could have left the surfaces more porous and pitted, as well as visibly altered in color, than is typically associated with eighteenth-century mercury-amalgam fire gilding. Moreover, she noted the exterior surfaces have lower levels of mercury than the interiors. See Appendix: Table 2. She surmises that a coating was applied to the interiors to prevent the reaction occurring on those surfaces. Technical Report for the lidded bowl (écuelle), 71.DG.77, November 5, 2021, updated December 3, 2021, and Quantitative X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy Table, December 9, 2021, by Julie Wolfe, Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

-

The three emblems on the shield represent mill rinds (anilles), which are four-armed iron supports for millstones. Rietstap, J[ohannes] B[aptista]. Armorial général: Précédé d’un dictionnaire des termes du blazon. 2 vols. 1887. Reprint edition, New York: Barnes & Noble, 1965., vol. 2, 272; Rolland, V[ictor], and H[enri] V. Rolland. Illustrations to the Armorial Général by J.-B. Rietstap. 6 vols. London: Heraldry Today, 1967., vol. 3, plate CCLV; Jougla de Morénas, Henri. Grand armorial de France: Nouvelle édition. 7 vols. Paris: Frankelve; Paris-Nancy: Berger-Levrault, 1975., vol. 5, Mar–Ric, 127. See note 28 below. ↩︎

-

The historic seat of the Moulinet d’Hardemare family was in Normandy, though the family had other property in the Île-de-France. ↩︎

-

The stand was not present when the écuelle sold in Collection D. David-Weill (deuxième vente d’orfèvrerie)—Orfèvrerie France XVe au XVIIIe siècle, sale cat., Palais Galliéra, Paris, November 24, 1971: lot 17, “Écuelle et son Couvercle en vermeil,” ill. In lieu of the missing stand, a note to the entry offered a different dish of later date: “Claude-Gabriel Dardet, reçu en 1715. Écuelle et son couvercle en vermeil. Le corps uni, grave d’armoiries à couronne de comte, porte deux anses ciselées de rinceaux, de feuillages et d’un médaillon à têtes d’homme et de femme. Le couvercle à moulure d’oves est ciselé de palmes, de coquilles, de rinceaux, de fleurons et de coquillages. Il est surmonté d’un bouton ciselé d’une tête de femme sur une terrasse ciselée de lambrequins. Vraisemblablement aux armes de la famille du Moulinet, originaire d’Ile-de-France. Paris, 1727. Un plat de même décor, d’époque postérieure, sert de présentoir et sera remis à l’acquéreur. Diam. du plat 0,255 Vente coll. Marquis, février 1890, no 10 du cat.” (“Claude-Gabriel Dardet, received [as a master] in 1715. Gilded-silver bowl and its cover. The plain body, engraved with an armorial with a count’s coronet, has two handles chased with scrolls, foliage and a medallion with heads of a man and a woman. The cover with an egg molding is chased with palms, shells, foliage, florets and seashells. It is surmounted by a knob chased with a woman’s head on a ground engraved with lambrequins. Presumably with the arms of the Moulinet family, originally from the Ile-de-France. Paris, 1727. A dish of the same decor, from a later period, serves as a stand and will be given to the purchaser. Diam. of the dish 0.255 Sold Marquis collection, February 1890, lot [1]10,” author’s translation). See note 32 below. ↩︎

-

Marius Paulme (1863–1928) was a student of the École des beaux-arts who went on to become an expert in the Paris sale rooms at the Hôtel Drouot, specializing in prints, old master drawings, paintings, and works of art. His personal collection consisted of sculptures and old silver. See the biography published online by the Fondation Custodia, Paris: “Paulme, Marius,” Frits Lugt: Les marques de collections de dessins et d’estampes, updated May 2014, http://www.marquesdecollections.fr/detail.cfm/marque/8553/total/1. ↩︎

-

Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001. http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/089236632X.html., 96, no. 193. On Dardet, see Nocq, Henry. Le poinçon de Paris: Répertoire des maîtres-orfèvres de la juridiction de Paris depuis le Moyen-âge jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. 5 vols. Paris: Léonce Laget, 1968., vol. 2, 10–11. ↩︎

-

Collection D. David-Weill, lot 17, “Écuelle et son Couvercle en vermeil,” ill. While the drawn illustration in the catalogue for Dardet’s mark corresponded to a second gilded-silver écuelle, and the Marquis provenance printed there actually corresponded to yet a different silver écuelle (now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. 1993.402a–b, see note 13 above), the lot was illustrated with a photograph of the Getty écuelle made by Louis Cordier. ↩︎

-

As per note 28 above, the 1971 sale catalogue entry explained, “A dish of the same style, of later date, serves as a stand and will be given to the purchaser” (“Un Plat de même décor, d’époque postérieure, sert de présentoir et sera remis à l’acquéreur”). Prior to that sale, there was a special presentation viewing of the more important objects. This viewing was held at Maison de la Chimie, 28 bis rue Saint-Dominique, Paris, on November 19, 1971. This écuelle and the dish are visible (from a distance) in photographs documenting that display. The fate of the later dish cannot be traced after 1973, and it is not in the museum’s current collection. Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, 2014.IA.27-03, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Art Objects, Ledger, A71-E2; 1986.IA.49 20010, Box 2, Department of Decorative Arts Records, Correspondence, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1971–1976 (1/2), Letter of October 4, 1972, from Frank Whitworth to Frederick J. Cummings, Director of the Detroit Institute of Art, and Box 4, Department of Decorative Arts Records, Correspondence, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1971–1976 (2/2), Letter of April 15, 1972, from Gillian Wilson to Frederick J. Cummings. ↩︎

-

The 1971 sale catalogue erroneously stated the Dardet écuelle had sold from the Marquis estate in February 1890, lot [1]10. See note 28 above and Catalogue des objets d’art et d’ameublement de l’Orient et l’Occident, lot 110 (not illustrated). ↩︎

-

Catalogue des objets d’orfèvrerie ancienne, 51, lot 183, “Écuelle à bouillon et présentoir, en vermeil,” ill. ↩︎

-

Collection D. David-Weill, lot 17, “Écuelle et son Couvercle en vermeil.” Lot 17 is illustrated with a photograph of the Getty écuelle, but the lot 17 text describes a different écuelle marked for Claude Gabriel Dardet (active 1715–before 1741, master 1715) and a dish said to be of later date. ↩︎