The process of survey planning expands on the findings of the needs assessment to provide a blueprint for how the survey will be resourced, managed, designed, and carried out. While there is no single approach to survey planning that fits all agencies and organizations, there are commonalities in the topics and issues to consider, and those are the focus of this chapter. Project administration is discussed in detail first, followed by an introduction to specific components of a survey to consider when developing a survey methodology; those elements are explored in further detail in the next two chapters.

The Plan

Survey planning culminates in a written survey plan. While survey plans may vary in format, content, and detail, certain general categories of information are recommended for inclusion, depending on the intended audience and the needs of the agency or organization supporting the plan. See the resource 7.1, Sample Survey Plan Outline (see also City of Toronto, City Planning Division. 2019. City-Wide Heritage Survey Feasibility Study. Toronto: City Planning Division. https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2019/ph/bgrd/backgroundfile-135182.pdf).

Resource 7.1 Sample Survey Plan Outline

Full Text

-

Introduction and Purpose of the Survey Plan

- Initiating and establishing the need for a survey

- Survey goals, objectives, and outcomes

- Benefits of the survey

-

Summary of the Planning Process

- Participants in developing the plan

- Research and design methods

-

Description of the Survey Scope

- Geographic area

- What will be surveyed

-

Survey Technology

- Data collection tools and technologies to be explored/used

-

Survey Methodology

- Survey standards and guidelines

- Evaluation criteria

- Prioritizing, phasing, and sequencing surveys

- Historic context and theme-based approach

- Recording processes and procedures

- Data management

- Pilot survey program

- Publishing and reporting

-

Public Outreach and Participation Program

- Outreach goals and objectives

- Participants and stakeholders

- Tools, strategies, and activities to be explored/used

-

Administrative Framework for the Survey

- Staffing, consultants, interns, and volunteers

- Costs and funding

- Schedule and timeline

- Conclusions and Next Steps

-

Suggested Attachments

- List of community participants

- Outreach meeting summaries

- Map of survey area

- Budget

- Staffing model

- Schedule

A primary audience for a plan may be decision-makers, such as a city or town council responsible for officially endorsing a survey and allocating or securing resources for its completion. The plan can also be used to introduce the survey to stakeholders and the general public, to encourage broad-based interest in the project, and to initiate community outreach efforts. Finally, the plan can serve as the starting point for a more detailed strategy to guide day-to-day survey project management.

Participants in Survey Planning

Recommended participants in survey planning include a project manager, interns, consultants, and survey stakeholders, some of whom may have been involved in the phase-one needs assessment. The manager may be internal to a lead agency or organization or may be part of a planning consultant team working with a lead agency or organization. A consultant team with contemporary experience and expertise in heritage surveys, inventories, and community outreach can provide information and make recommendations relating to project staffing, costs, and schedule, as well as for tools, methods, and technologies.

Organizations, groups, and individuals representing a range of interests in the survey can help shape decisions about what will be surveyed, how the community can be involved, and what public engagement strategies will be explored; they can also identify opportunities for potential collaborations and partnerships. Activities may include public events and more targeted workshops, meetings, and interviews. Finally, information sharing with heritage organizations and agencies that have recently completed surveys or have one in process can also provide direct, practical advice for survey planning.

Survey Administration

Survey planning includes developing a framework for overall project administration. The managing agency or organization must address issues relating to four key and interdependent factors: project personnel, budget, funding, and schedule, as described below.

Survey Personnel

Survey planning will identify positions needed to manage and carry out a survey project in light of the size and scope of the survey, the skill sets needed, and available funding. Because financial resources are often limited for surveys, creative approaches may be needed to consider how funds might be secured and allocated (and potentially augmented) to fill full- or part-time staff positions, engage external consultants and other specialists, and supplement staff and consultant time with interns and volunteers. The section Considerations and Recommendations for Assembling a Survey Project Team, at the end of this chapter, defines key positions to consider, as well as the role of volunteers and interns.

Survey Budget

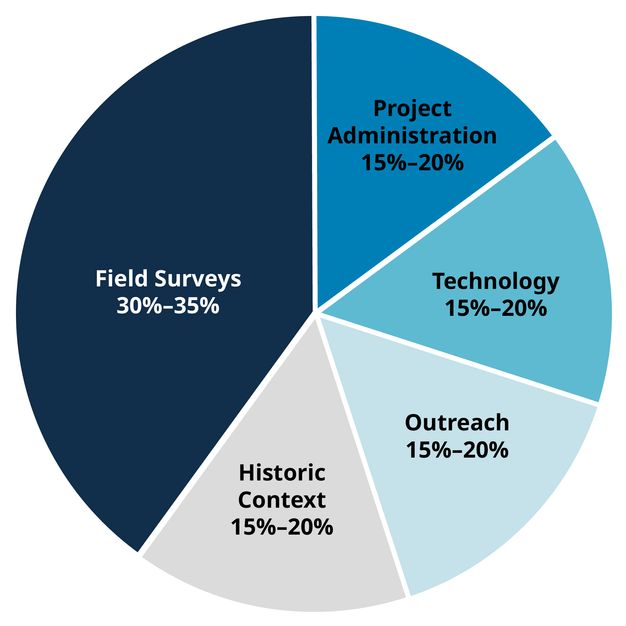

Estimating the costs associated with a survey will establish budgets for the project as a whole and for its various components. Project expenses are highly dependent on factors relating to the size and scope of the survey, adequate and qualified project personnel, technological infrastructure, state of an existing inventory data or previous survey data, available research and scholarship on the area’s heritage resources, and the scope of outreach programs and activities. Figure 7.1 is a budget model with the main cost categories for a survey depicted as percentages of the total budget, based on the experiences of SurveyLA.

Table 7.1 shows a breakdown of the primary expenses within each category. Note that these expenses may not all be relevant for every survey; for example, small-scale surveys or those highly reliant on community involvement and the use of volunteers can reduce or avoid some costs.

| Project administration | Technology and information management | Field surveys | Historic contexts/thematic studies | Outreach and volunteer program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency/organization staff | Agency/organization staff | Agency/organization staff | Agency/organization staff | Agency/organization staff |

| Consultants | Consultants | Consultants | Consultants | Consultants |

| Interns | Interns | Interns | Interns | Interns |

| Project advisors | Software/hardware | Reports/publications | Publications | Project website |

| Equipment and supplies | Review committee | Outreach activities (meeting location fees, refreshments, etc.) | ||

| Project advisors | Publications/production | |||

| Multilingual translation |

While it is necessary to develop at least a preliminary project budget to secure a commitment to complete a survey, it is important to expect that the budget may need to be revised once the project is initiated and survey tools and methods are tested and further defined. Pilot surveys are central to estimating the time and budget needed to complete the field surveys, as discussed in chapter 9.

Survey Funding

The planning phase will identify potential funding sources and opportunities for the survey, which may include lead agency/organization resources, grants, and partnerships, as described below.

Agency/Organization Resources

The lead agency or organization for the survey must commit sufficient funds and/or identify sufficient supplemental funding sources to complete the survey. A long lead time may be required to allocate funds for a survey into annual budgets, and a phased survey approach or methodology may be necessary as a result. Creative approaches to funding could include leveraging financial resources from existing programs that overlap with the goals of the survey. For example, within a municipal planning department, a survey might dovetail with already-funded community planning activities and programs that rely on up-to-date and comprehensive heritage data, so surveys could be incorporated into those efforts. Interagency funding opportunities could result from collaborations with museums, libraries, universities, and associated cultural heritage programs.

Grants

Grants can be an important source of supplemental funding for heritage surveys; however, they take time to administer, and in many cases require matching funds. Grant opportunities can be explored during the planning process and throughout the project, such that available funds and funding cycles can be accounted for in the overall project budget and schedule over the life of a survey.

Partnerships

Budget planning can include examining the opportunity to establish partnerships with universities and other research institutions, the private sector, and charitable foundations to help support the costs of the survey. Like grants, partnerships may provide funding for the project in whole or in part. As mentioned in chapter 5, the work of the Getty Conservation Institute to establish a blueprint for a citywide survey in Los Angeles resulted in the multiyear partnership and associated grant agreement between the J. Paul Getty Trust and the City of Los Angeles to complete SurveyLA. After the official launch of SurveyLA, the GCI funded work associated with the citywide historic context and project technology and also helped to implement Arches as the city’s heritage inventory system.

Survey Schedule and Timeline

Developing a realistic schedule for a survey is important to managing the expectations of the lead agency or organization, stakeholders, and the public regarding how the project will unfold over time. The overall project schedule may be based on variables such as the size and scope of the survey, available resources for its completion, and the urgency of data needs. The schedule guides the work plan for the survey and typically incorporates a timeline for the project as a whole, as well as for each individual activity of the survey: when each will start and end, and areas of overlap.

Elements of the Survey

Survey elements or components are identified during survey planning to drive the development of survey tools, methods, processes, and procedures.

Technologies for Data Collection and Management

Survey planning is the time to develop a strategy to fully explore technology options and approaches for data collection and management. Surveys are ideally designed for compatibility between the field data collection system and the associated inventory information system: these systems should be in accord with respect to data structures and standards. While this is the ideal, in reality, many agencies that initiate new surveys have no existing digital inventory or have inventory systems that need to be updated or made more robust.

Creating or modernizing and improving a digital inventory system, including building a compatible data collection system, needs to happen in advance of or concurrent with a survey project. This effort can require a substantial commitment of time and funds to cover the costs associated with hardware, software, and personnel, including specialized IT consultants. Sometimes resources are made available to do this; sometimes resources are limited and only half measures are taken. These issues need to be seriously considered when making decisions about survey technology. If only half (or even more partial) measures are taken to address deficiencies in the inventory system, it will likely result in later problems. While new technologies present opportunities for improving how and what data can be captured, they should ultimately serve the survey requirements and methodologies—not drive them. (See part I for detailed information on building and modernizing heritage inventories.)

Survey Standards and Guidelines

Official survey standards and guidelines have been developed and published by national agencies worldwide and are commonly used (or adapted for use) to develop regional and local guidelines. Applicable standards for a jurisdictional area should be identified and considered as the foundational element for a survey to provide technical assistance for survey planning and developing survey tools and methods.1 Adopting such standards will help ensure consistency in survey practices and that the survey follows accepted professional practices, meets applicable legal requirements for heritage preservation, and is credible and defensible.2 The use of standards is particularly important in instances where survey findings are officially approved, adopted, and incorporated into an authoritative inventory. Chapter 8 discusses the application of standards and guidelines to developing survey recording and documentation tools and methods.

It is important to acknowledge that, in many cases, existing standards and guidelines are outdated. For example, data fields required for old paper survey forms may refer to specific ways to record spatial information that are no longer pertinent for digital data collection. As well, standards and guidelines may not apply to documenting the range of themes and heritage typologies that characterize modern surveys, such as intangible heritage. The planning phase is a critical time to assess and address the relevancy of these survey standards for a modern survey.

Historic Preservation Practice in the United States

Following passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA), the U.S. Department of the Interior and the National Park Service (NPS) prepared extensive standards and guidelines concerning historic preservation activities carried out under federal programs, state and local level governments, and private parties (National Park Service. 1983. Archaeology and Historic Preservation: Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/upload/standards-guidelines-archeology-historic-preservation.pdf). This guidance serves as nationally accepted professional standards for historic preservation practice and ensures a uniform and consistent process for documenting and evaluating historic properties through surveys or property designations. The concepts and terms discussed here comprise the basic elements of these national professional standards.*

Historic Property

The terms historic property and historic resource are used interchangeably in the United States to refer to buildings, structures, objects, sites, and districts that have been evaluated as significant (National Park Service. 1997b. How to Complete the National Register Registration Form. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB16A-Complete.pdf):

Building. A building . . . is created principally to shelter any form of human activity.

Examples are residences, schools, churches, factories, theaters, and stores.

Site. A site is the location of a significant event, a prehistoric or historic occupation or activity, or a building or structure, whether standing, ruined, or vanished, where the location itself possesses historic, cultural, or archaeological value regardless of the value of an existing structure.

Sites include cemeteries, designed landscapes, cultural landscapes, and natural features.

Structure. The term “structure” is used to distinguish from buildings those functional constructions made usually for purposes other than creating human shelter.

Examples include bridges, roadway systems, dams, and tunnels.

Object. The term “object” is used to distinguish from buildings and structures those constructions that are primarily artistic in nature or that are relatively small in scale and simply constructed.

An object is associated with a specific setting or environment, although it may be movable. Examples include sculpture, statuary, and fountains.

District. A district possesses a significant concentration, linkage, or continuity of sites, buildings, structures, or objects united historically or aesthetically by plan or physical development.

Districts include residential neighborhoods, commercial areas, civic centers, industrial complexes, and institutional campuses such as hospitals and universities.

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States’ official inventory of historic places worthy of preservation. The NPS established the National Register to identify properties of architectural, historical, engineering, or archaeological significance at the local, state, or national level.† The National Register provides standardized criteria for evaluating properties for significance (National Park Service. 1997a. How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB-15_web508.pdf). These criteria have been adapted for use by most state and local governments in developing their own designation programs and are also applied to properties during survey work.‡

To be listed in the National Register, a property must meet at least one of the criteria set forth in How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation (National Park Service. 1997a. How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB-15_web508.pdf; see below) and retain integrity of those features necessary to convey its significance.§

The quality of significance in American history, architecture, archaeology, and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association, and:

A. that are associated with events that have made significant contributions to the broad patterns of our history; or

B. that are associated with the lives of persons significant in our past; or

C. that embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or

D. that have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in prehistory or history

Historic Context Statements and the Multiple Property Documentation Approach

A historic context statement is a narrative, technical document specific to the field of historic preservation. Contexts organize information about important trends, patterns, and topics significant to the development history of a defined geographic area into themes, and then relate those themes to property types that share common physical and associative attributes.

Historic context–based surveys are the foundation of preservation planning in the United States. They provide a framework for establishing preservation goals and priorities and ensure consistency in resource identification and evaluation. Contexts can address a single theme and property type, such as Midcentury Modern residential architecture, or can provide a comprehensive summary of all aspects of history of an area.

The multiple property documentation (MPD) approach developed by the NPS is the format most used for context-based surveys in the United States (National Park Service. 1999. How to Complete the National Register Multiple Property Documentation Form. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB16B-Complete.pdf). Although designed to streamline the nomination of properties related by theme to the National Register, the MPD approach is also highly effective in conducting heritage surveys, particularly at a large scale. This approach provides a narrative discussion of themes; identifies and describes property types that represent the themes; and, importantly, provides specific guidance and comparative analysis regarding the physical characteristics, associative qualities, and aspects of integrity a property must have to be an important example of a property type and eligible for designation.

The sidebar Historic Preservation Practice in the United States summarizes national survey standards used in the United States, which formed the basis for the SurveyLA methodology.

Survey Evaluation Standards

Evaluations or assessments of resource significance are typically made using official criteria established by laws, regulations, and other legislative actions that govern heritage practice in a particular jurisdiction. These criteria have been developed to guide processes for nominating and designating or listing resources in local, regional, national, or world heritage registers, but they are also commonly used for survey evaluations. Applying established criteria, and their associated thresholds for significance and other guidelines, can result in consistent classification or identification of resources and provide important information for heritage management, even though resources evaluated in a survey may not ultimately be listed or designated.

Like survey standards and guidelines, evaluation criteria may need to be enhanced or updated to align with current survey practices, such as to address a wider range of heritage types than previous surveys. See chapter 8 for more information on using evaluation criteria for surveys and chapter 10 for more on making assessments of significance.

Historic Context– and Theme-Based Surveys

The concepts of historic contexts and thematic frameworks, as defined in the sidebar in chapter 2, can be applied to heritage surveys to consistently identify, categorize, and evaluate resources that reflect important aspects of the history and development of an area. The planning phase is the time to consider if a context- and/or theme-based approach will be used for the survey and how the approach will be developed and implemented. Taking such an approach can be a substantial undertaking, depending on the scope and size of a survey, and it can impact survey budget, schedule, and personnel needs. Chapter 8 draws on the example of SurveyLA to provide useful information for designing historic context– and theme-based surveys.

The Role of Community Outreach and Engagement

The public can be engaged in heritage surveys in many ways. The extent and type of outreach approaches considered will reflect the overall goals of the survey as well as available funding and staffing. Survey planning may engage key stakeholders and others with a clear understanding of the scope and content of the survey and expertise in developing and implementing a range of community outreach strategies for heritage work. See Public Outreach and Engagement in chapter 8.

Pilot Surveys

A pilot survey program serves as a test run to assess and refine tools, methods, and procedures in advance of the official launch of field surveys. The pilot may include one or more geographic areas, themes, and resource types. See chapter 9 for details on completing pilot surveys.

Considerations and Recommendations for Assembling a Survey Project Team

Considerations for putting together a project team may include the survey scope and approach; internal staffing capacity; the need for specialized knowledge, skills, and expertise; and project budget and funding. Multilingual needs and relevant professional qualification standards are also considerations when selecting project participants.3

In some instances, a survey may be wholly completed by agency or organization personnel. In other instances, it may be necessary to bring on temporary personnel for the duration of the project, or to use external consultants. A request for qualifications (RFQ) process can be an effective way to create a prequalified list of consultants who best meet the skills and competencies needed for a survey. Consultants on the list can form a range of collaborations and partnerships to build strong and diverse teams whose members’ skills supplement and complement the others’.

Key Survey Team Positions and Responsibilities

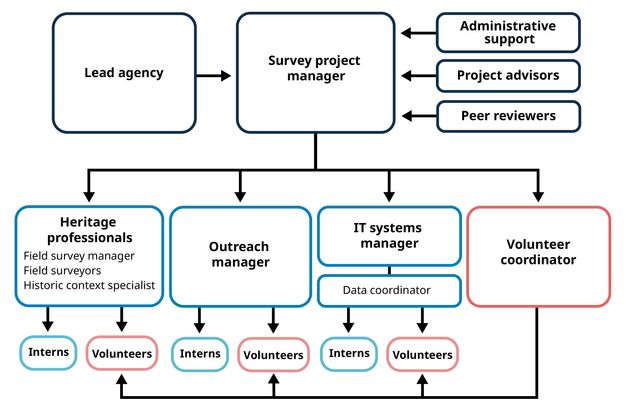

Key survey team positions and responsibilities, including volunteers and interns, are illustrated in the survey team model in figure 7.2.

The model can be applied or adapted to a range of survey types, as not every survey will require every position described below, and some surveys may be highly dependent on community outreach and the use of volunteers.

-

Survey project manager is the lead position for the survey project and is responsible for implementing the survey plan, overseeing the day-to-day activities of the survey, supervising project personnel, and keeping the survey on schedule and within budget. The project manager may also be responsible for securing project funding, acquiring and managing grants, and serving as the main point of contact for the public. In some cases, project management responsibilities may be shared by agency or organization staff and consultants, particularly in cases where allocating full-time staff is not feasible or practical or where the management skills needed for the project are better fulfilled by qualified consultants.

-

The field survey manager plays a lead role in planning, designing, developing, and implementing survey tools and methods. The survey manager supervises and directs the work of field surveyors and is responsible for their safety and well-being. Ultimately, the survey manager ensures data is high quality and consistent and that surveys are completed on time and on budget. A large-scale survey may have one or more field survey managers.

-

Field surveyors complete surveys under the direction of the field survey manager. The number and profile of field surveyors needed may depend on factors including technology used, size of the survey, level of detail required, experience needed, and the survey budget and schedule.

-

A historic context specialist is recommended for surveys that implement a historic context–based approach. This role may be a function of the field survey manager or other heritage professionals who have extensive experience designing thematic frameworks and writing historic context statements or thematic studies.

-

The outreach manager is responsible for leading the development of a community outreach and participation plan for the survey and implementing it. The amount of time dedicated to outreach can depend on the size and scope of the survey, as well as the overall role of outreach defined in the goals and objectives of the survey. For surveys that are large scale (e.g., citywide), community-based, and/or focus on underrecognized communities, a full-time outreach manager is recommended.

-

The volunteer coordinator is responsible for developing and managing a volunteer program for the survey. This position may dovetail with outreach activities. For surveys that are highly reliant on volunteer participation and require a broad-based volunteer program, a full-time coordinator may be needed.

-

The information technology systems manager provides support for the data collection system used by the field surveyors. The IT systems manager may assist with developing, enhancing, and customizing data collection tools to meet the needs of the survey. The position may also assist with integrating heritage data from the inventory (and potentially other systems) into the survey data collection system, and vice versa. The position will be most effective if established during the early stages of the survey associated with developing data collection methods and standards. IT systems manager may be the role of personnel managing an existing inventory system; for example, the database administrator role discussed in part I.

-

The data coordinator is responsible for processing survey data, assuring data quality, and integrating final data into the related, or newly developed, inventory. Data coordination may be the role of personnel managing an existing inventory system—for example, the data editor role discussed in chapter 2.

-

Administrative support includes part-time agency or organization staff that assist the project manager with various aspects of project administration, such as grant management and consultant contracting.

-

Peer review experts are engaged to review and vet survey findings and may be organized as a committee or panel. The Peer Review in Heritage Surveys sidebar in chapter 10 provides more information on the role and process of peer review. Peer reviewers may be paid project personnel whose time is considered in the project budget. The five members of SurveyLA’s peer review committee were paid a stipend to prepare for and attend each meeting.

-

Project advisors provide expert advice on various aspects of the project, as well as overall support for the survey. Although advisors may be individuals, a project advisory committee is recommended to bring a range of stakeholders to the table and provide consensus on important topics. The makeup of an advisory committee will vary based on the scope and focus of the survey and the goals and objectives established for the committee. Participants may be internal or external to the managing agency or organization and may be volunteers or paid project personnel whose time is considered in the project budget. SurveyLA’s volunteer advisory committee was composed primarily of community-based stakeholders; they met on a quarterly basis while survey tools and methods were in development and less often as the field surveys were in progress. The committee provided advice on topics ranging from naming the survey to ensuring inclusive participation in the project.

Tips for Utilizing Interns and Volunteers

Student interns are project support personnel with education and training in heritage conservation, archaeology, urban planning, or related fields of study. While interns may be undergraduate or graduate students, those from graduate programs in conservation are particularly valuable, as they generally have the relevant skill set. Partnerships with local colleges and universities offer opportunities to recruit interns. Through survey experience, student interns receive invaluable practical training in their respective fields, often for academic credit.

Interns work under the direct supervision of project staff and/or consultants in completing aspects of the survey project. They should not be given responsibility for tasks for which they do not have sufficient experience or do not meet applicable qualification standards, such as completing assessments of heritage resource significance. It is important to note that interns need mentoring, training, and supervision, and these can take substantial time.

Intern programs are most effective when they are manageable in size. Limiting the number of interns provides the maximum learning experience for students while ensuring the quality and credibility of the survey. The ways that interns can contribute to the survey project are discussed in more detail in the chapters that follow and in particular in chapter 10.

Volunteers can play a critical role in supplementing the work of project staff, consultants, and interns while also building public support and buy-in for the survey. Like internships, volunteer programs require substantial resources and must be adequately staffed. A volunteer program may benefit from partnerships and resource sharing with heritage organizations and other stakeholders in the survey that have extensive and well-established volunteer programs.

Although volunteers may have a variety of skill sets, they will have in common a desire to feel a part of and contribute meaningfully to the survey. A well-designed volunteer program identifies and describes specific opportunities that account for a range of skills and also establishes qualifications, work programs (including expected time commitments), and relevant training needed for each activity. In this way, potential volunteers have a clear understanding of what activities may or may not be available to them. The roles of volunteers in various aspects of a survey are discussed in subsequent chapters where relevant.

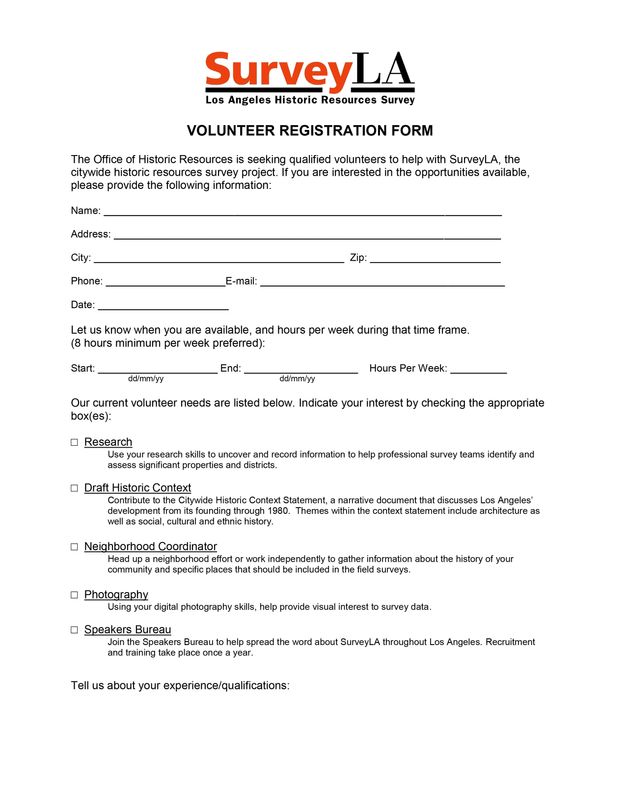

Volunteers, like interns, are not recommended for tasks that require specialized professional training, experience, and qualifications or that may have implications for credible and defensible survey results. A volunteer intake questionnaire, such as the one used for SurveyLA shown in resource 7.2, can aid in the process of engaging community members with a range of skills and matching them with tasks that align with individual interests and skills.

Resource 7.2 SurveyLA: Volunteer Registration Form

Download Form Download the PDF

Full Text

Notes

-

For local jurisdictions where no survey standards have been developed, regional or national standards may be used. ↩︎

-

Most heritage agencies publish standards and guidelines on their associated websites. ↩︎

-

A number of countries, including the United States and United Kingdom, have qualification standards for heritage professionals. ↩︎