History of Photography

|

|

This section includes materials dealing explicitly with the history of photography in China and lists publications and Chinese and English websites dedicated to the study of the subject. Some surveys tackle nationwide as well as local photographic history in China, while others arrange photographs chronologically, mainly as historical documents. The second through fourth sub-sections focus on monographs and articles by or about photographers, as well as photographs by missionaries, archaeologists, scientists, scholars, travelers, and other amateurs. It should be noted that a large number of photographs taken in nineteenth-century China are unattributable. For example, some of the studio photos are attributed to the owner of the photographic studio, rather than to the photographer.

|

|

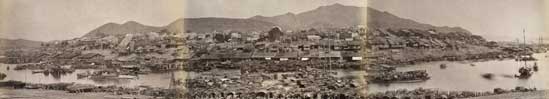

From its inception, photography was associated with other technologies linked to the colonial powers that gained ground in China during the nineteenth century, which partly explains the prominent presence of Western photographers. According to Imperial China (Worswick and Spence, 1978: 150–51), from 1846 to 1912 there were 84 commercial and amateur photographers in China; 60 of them were Westerners. Some of the best-known early photographers are Felice Beato (ca. 1825–ca. 1908), Milton Miller (active 1860–64), William Saunders (active 1862–88, d. 1892), and John Thomson (1837–1921). In 2009, Terry Bennett, in his History of Photography in China, 1842–1860, significantly expanded this list. Chinese photographers from this period are not as well known, although photographers such as Lai Afong (often known as simply Afong, 1839–90) and Liang Shitai (also known as See-Tay, active 1870s–1880s) were prolific and successful commercial photographers. While a large number of photographs from their studios have survived, no scholarly monograph has thus far concentrated on them exclusively. Today, this lacuna is gradually being filled in by scholars in both China and abroad who are increasingly turning their attention to relatively unknown Chinese photographers.

The fifth subsection, on early publications and journals related to historical photographs of China, provides evidence about the circulation in foreign journals of early photographs concerning China. Also listed here are important early Chinese books and documents on photographic techniques, which were sometimes translated from Western manuals but often reinvented in the Chinese context.

The sixth subsection, on photographic postcards, reveals photography as another aspect of visual and material culture during the late Qing. First produced in China in the late 1890s, postcards became an important print medium characterized by a wide range of photographic images that reflected China in ways that could be successfully marketed to largely foreign consumers.

The final subsection, devoted to websites and online bibliographies, provides dynamic, ever-growing online references concerning the history of photography in China.