Apocalypse

Today it is difficult to imagine Pompeii and the other Vesuvian cities without thinking of their catastrophic demise in A.D. 79, as if they were destined for destruction. The obliteration was so sudden and so complete that Pompeii has become the archetype for subsequent disasters, invoked to convey the devastation of the American Civil War, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the attacks of September 11, Hurricane Katrina, and other great disasters.

While many 18th- and 19th-century artists viewed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius through contemporary ideas of the "Sublime"—celebrating the terrifying yet beautiful power of nature—more recent artists have employed it to explore issues involving the aftermath of World War II and the angst of the Atomic Age.

While many 18th- and 19th-century artists viewed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius through contemporary ideas of the "Sublime"—celebrating the terrifying yet beautiful power of nature—more recent artists have employed it to explore issues involving the aftermath of World War II and the angst of the Atomic Age.

Eruption

The erupting volcano and the roiling sea dominate this apocalyptic composition by Pierre Henri de Valenciennes, as the death of naturalist Pliny the Elder unfolds in the foreground. Pliny falls into the arms of his two slaves, as mentioned in the famous account of the event by his nephew, Pliny the Younger:It was daylight now elsewhere in the world, but there the darkness was darker and thicker than any night. They decided to go down to the shore, to see from close up if anything was possible by sea . . . . Then came a smell of sulfur, announcing the flames, and the flames themselves, sending others into flight, but reviving him. Supported by two small slaves, he stood up, and immediately collapsed.Here Valenciennes depicts the demise of the preeminent naturalist of the ancient world with its greatest natural disaster, adding massive clouds of ash and collapsing architecture, thereby intensifying the sense of catastrophe.

Flight from Pompeii, 1873, Giovanni Maria Benzoni (Italian, 1809–1873). Marble, 42 11/16 x 27 in. (108.5 x 68.6 cm). Art Institute of Chicago, 1900.83. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. S. M. Nickerson, 1900.83. Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago

Doomed Flight

The motif of a Pompeian family's attempted escape from the eruption captured the imagination of many 18th- and 19th-century artists. Their depictions were partly influenced by published reports of the discovery of skeletons of parents with children and later by the plaster casts of the lost victims.Giovanni Maria Benzoni leaves the fate of this young family ambiguous in this sculpture, though clumps of ash on their garments add pathos and hint at an ominous and futile end, while artifacts at their feet—including ancient coins, jewelry, a lamp, and even bread loaves—are precise copies of finds housed in the Naples museum.

Victims of Vesuvius

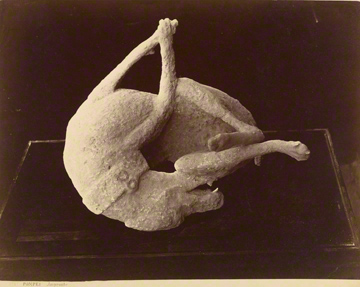

Since the rediscovery of the ancient Vesuvian cities in the 1700s, the casualties of the volcanic disaster have fascinated modern audiences. Early excavators encountered skeletons and realized that decayed organic material had left cavities in the hardened ash and pyroclastic flow that buried the sites. Few objects, however, have captured the imagination as much as the body casts of Vesuvius's fatalities. The casting technique was first employed successfully in 1863 by Giuseppe Fiorelli, director of the excavations at Pompeii, who poured plaster into a void left in the volcanic debris, creating a three-dimensional image, seemingly frozen at the moment of death.

To explore how artifacts could "represent this enormous, monumentally sad absence of a whole world we'll never retrieve again," Allan McCollum copied a second-generation cast of the iconic dog found in November 1874 in the House of Orpheus at Pompeii ("Pompei" in modern Italian). For the artist, the repetitive process of casting amplifies this sorrow.

(Quote from William S. Bartman and Thomas Lawson, Allan McCollum, 1996)

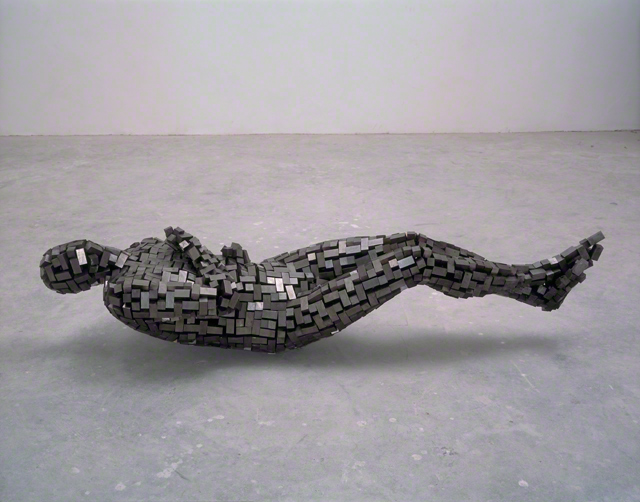

Antony Gormley made three sculptures inspired by the victims of Vesuvius, which he described this way in a correspondence of February 26, 2010:

The bodies each lie or crouch in their unique position of facing death, but they do not have the morbidity of the mummy, more a direct existential appeal reminding us that life can end at any time, whether during a trip to the shops or while sleeping . . . . The abstracted bodies of Pompeii A.D. 79 model the end of the human project and give us a foretaste of our own demise, in the manner of the dinosaur skeleton but much more immediate. I made three pieces, inspired by a visit in 2002, all of which try to think about a lack of air, fallout, and the end of time.

Publication

The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection

By Victoria C. Gardner Coates, Kenneth Lapatin, and Jon L. Seydl

By Victoria C. Gardner Coates, Kenneth Lapatin, and Jon L. Seydl