Cycle of Life, 1905–10

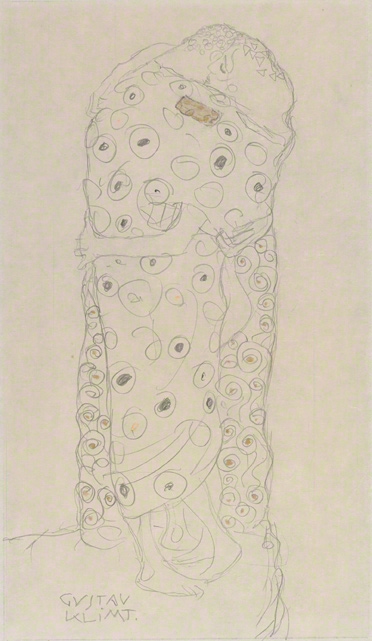

Standing Couple Embracing (Study for The Kiss), 1907–8, Gustav Klimt. Graphite, red pencil, heightened with gold. Albertina, Vienna, Batliner Collection

» See Klimt's painting The Kiss on the Galerie Belvedere website.

» See Klimt's painting The Kiss on the Galerie Belvedere website.

In 1905 Klimt left the Secession group in order to follow an increasingly personal artistic path. He further explored the notion of the cycle of life, which he had already started to address in his metaphysical paintings Medicine and Philosophy. This theme was of great importance to him, for it raised essential philosophical questions about the fate and the frailty of human life.

Klimt's depictions of life and its essential states of being (procreation, birth, youth, old age) always include some allusion to death. In fact, the idea that life and death are inseparable, that life is always death at the same time, was firmly anchored in the culture of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

The artist's beliefs were nourished, notably, by the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (German, 1788–1860), who stressed man's bondage to "the Will," the inescapable force that impels humanity from the cradle to the grave and the source of all desire and grief.

Even though Klimt saw mankind as caught in the inexorable grip of the endless cycle of life and death, he found solace in the life-affirming forces of love and procreation, whose sacred character he celebrated with astonishing poetical force in such highly ornamental, modern icons as The Kiss. See Klimt's painting The Kiss on the Galerie Belvedere website.

In this study at right, Klimt explored a standing pose, which was to signify the apotheosis of the union between man and woman in The Kiss. Resplendently ornamented cloaks bind them into a single unified column. Silhouetted against the blank page in the drawing (the glittering cosmos in the final painting), they stand on the edge of the world, as symbols of the love that redeems humanity from its suffering.

Klimt's depictions of life and its essential states of being (procreation, birth, youth, old age) always include some allusion to death. In fact, the idea that life and death are inseparable, that life is always death at the same time, was firmly anchored in the culture of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

The artist's beliefs were nourished, notably, by the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (German, 1788–1860), who stressed man's bondage to "the Will," the inescapable force that impels humanity from the cradle to the grave and the source of all desire and grief.

Even though Klimt saw mankind as caught in the inexorable grip of the endless cycle of life and death, he found solace in the life-affirming forces of love and procreation, whose sacred character he celebrated with astonishing poetical force in such highly ornamental, modern icons as The Kiss. See Klimt's painting The Kiss on the Galerie Belvedere website.

In this study at right, Klimt explored a standing pose, which was to signify the apotheosis of the union between man and woman in The Kiss. Resplendently ornamented cloaks bind them into a single unified column. Silhouetted against the blank page in the drawing (the glittering cosmos in the final painting), they stand on the edge of the world, as symbols of the love that redeems humanity from its suffering.

Hope I & Hope II

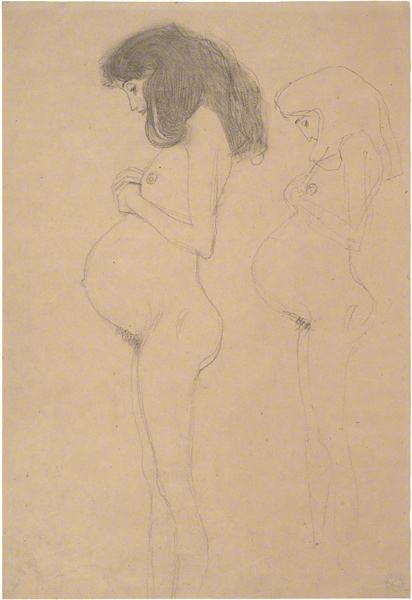

In the years following the Beethoven Frieze, Klimt continued to develop distilled profile views of nudes, articulated in flowing, continuous lines. Out of his grand artistic statements on the human condition such as Medicine and the Beethoven Frieze, he began to isolate individual themes for artistic treatment.

Having included a pregnant woman in the upper section of Medicine, Klimt treated pregnancy as a separate subject in the painting Hope I (1903–4). The drawing above is a study for the painting. Klimpt selected a profile view, which rendered the already scandalous depiction of a naked pregnant woman even more revolutionary.

Instead of the hopefulness of new life, the painting (view the painting on the National Gallery of Canada website) is suffused with dread as a skeleton looms over the unsuspecting expectant mother. The finished painting was deemed so risqué that its male owner kept it in a special box. In 1907–8 Klimt treated the subject again in the painting Hope II but in this case envisioned as a monumental, geometrical symphony in which death plays a much smaller role. See Klimt's painting Hope II on the Museum of Modern Art website.

Instead of the hopefulness of new life, the painting (view the painting on the National Gallery of Canada website) is suffused with dread as a skeleton looms over the unsuspecting expectant mother. The finished painting was deemed so risqué that its male owner kept it in a special box. In 1907–8 Klimt treated the subject again in the painting Hope II but in this case envisioned as a monumental, geometrical symphony in which death plays a much smaller role. See Klimt's painting Hope II on the Museum of Modern Art website.