Beethoven Frieze

In 1901–2 Klimt worked on a groundbreaking decorative cycle, the Beethoven Frieze, which was displayed in the Secession building, where it still is today. It was a painted interpretation of one of the greatest musical compositions ever written, the final choral movement of Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (1824).

Klimt drew inspiration for the paintings from ancient Greek, Byzantine, early medieval, and Japanese art as well as from such contemporary artists as Jan Toorop, Fernand Khnopff, George Minne, Ferdinand Hodler, and Edvard Munch. He synthesized these varied sources into an entirely new stylistic vocabulary, arranging the figures of the frieze either frontally or in profile, and subjugating their bodies to strong horizontals and/or verticals. The creative process of this highly ambitious project can be seen in numerous preparatory drawings.

See images of the Beethoven Frieze and learn more about it on the Secession website »

Klimt drew inspiration for the paintings from ancient Greek, Byzantine, early medieval, and Japanese art as well as from such contemporary artists as Jan Toorop, Fernand Khnopff, George Minne, Ferdinand Hodler, and Edvard Munch. He synthesized these varied sources into an entirely new stylistic vocabulary, arranging the figures of the frieze either frontally or in profile, and subjugating their bodies to strong horizontals and/or verticals. The creative process of this highly ambitious project can be seen in numerous preparatory drawings.

See images of the Beethoven Frieze and learn more about it on the Secession website »

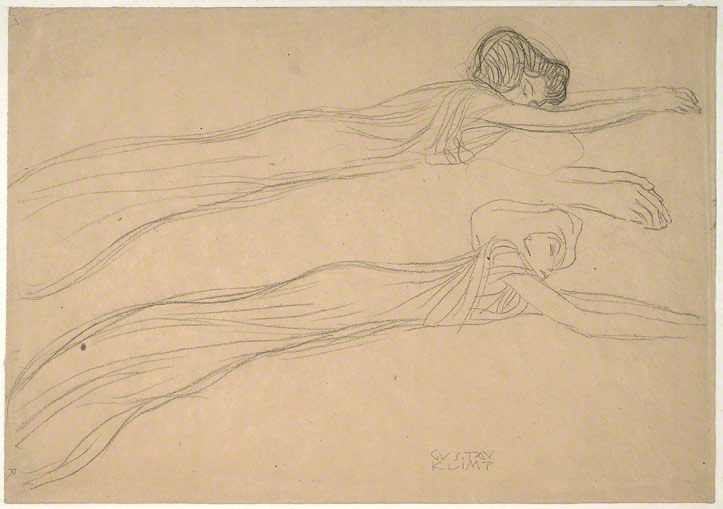

The frieze runs across three walls of a long and narrow room in the Secession building, with scenes proceeding from left to right. The first wall of the frieze starts to the left with a long chain of floating genii, symbols of the "yearning for happiness," a motif that reappears in other parts of the cycle and connects single scenes. The first incident involves a knight who is being implored by "weak mankind" and driven by "compassion and ambition" to take on the fight for happiness on their behalf.

In order to study the figures of the flying genii, as in the drawing above, Klimt had a model wear a robe and lie down with arms stretched. In a linear vocabulary very much his own, he grasped the flowing movement, whose effect he intensified by repeating the figure in parallel. The forms of the body are still discernible, in spite of the high stylization of the garment.

In order to study the figures of the flying genii, as in the drawing above, Klimt had a model wear a robe and lie down with arms stretched. In a linear vocabulary very much his own, he grasped the flowing movement, whose effect he intensified by repeating the figure in parallel. The forms of the body are still discernible, in spite of the high stylization of the garment.

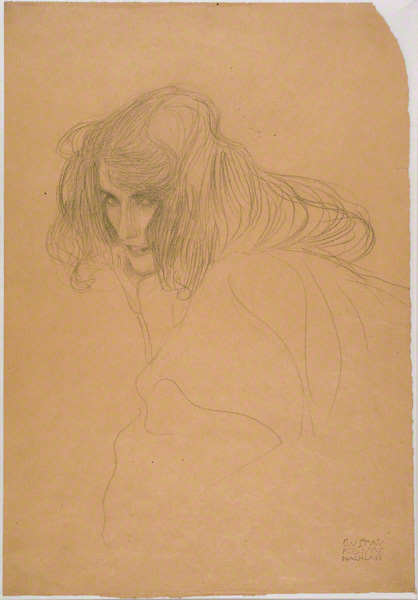

The central wall of the Beethoven Frieze features the "hostile forces" that are confronted on the way, such as three gorgons and "Laciviousness." In the study for "Lasciviousness" above, a sexy young woman, shown in three-quarter profile, stares out provocatively through peekaboo waves of hair. Seductive and ominous, she exemplifies the femme fatale that populated much European art about 1900. In the final painting, "Lasciviousness" is a red-haired figure; for Klimt and other contemporary artists, red hair symbolized sexual appetite.

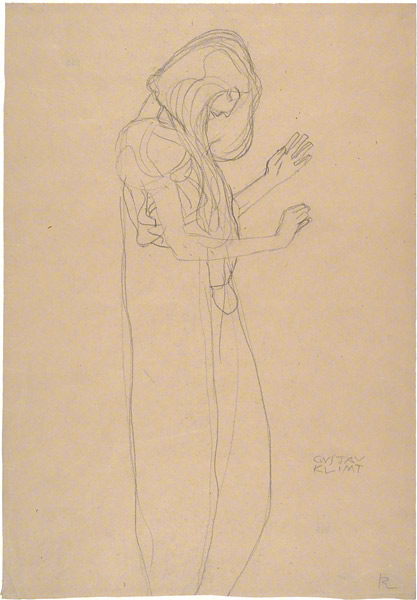

On the third and final wall of the frieze, the yearning for happiness finds "appeasement in poetry." The drawing above is a study for the image of Poetry. Hieratic and self-absorbed, the model is clothed in a long robe, yet she is still lacking her instrument. Her hands protrude at an angle on the page, creating an elegant rhythm with her bowed head. Klimt subtly contrasted taut, angular lines with freely flowing ones.

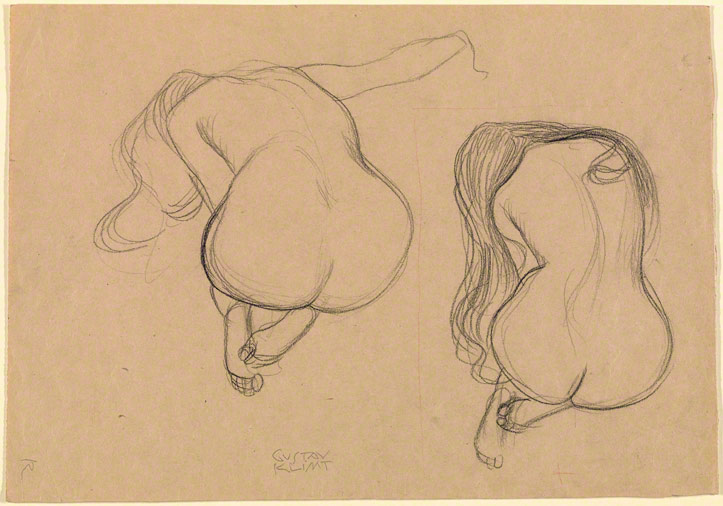

This pair of life drawings shows the same model, her hair cascading around her head like rivulets

of water. The dramatic, curved contours of the model's body and hair evoke Klimt's identification

of women with water, a common motif in his work. He made this drawing as a study for a painting, Goldfish, which was contemporaneous with and aesthetically akin to his work on the Beethoven Frieze. Klimt seems to have considered the drawing a work of art in its own right. Not only did he sign it, but he also published a reproduction of the right figure in the Secession periodical Ver Sacrum. The red pencil marks are cropping indications for the photographer.