|

|

|

|

|

Like all artworks, the objects in this exhibition are informed by their historic and contemporary contexts. They are normally viewed either in the galleries of the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center, where sculpture and decorative arts are displayed in interiors designed to evoke a particular period (below left), or as part of the collection original, or later added, to Temple Newsam House (below right). Their display in these contexts offers a historic anchor, influencing the visitor's experience of the object and perception of its form, function, style, and meaning.

|

|

|

|

|

Paneled room at the J. Paul Getty Museum with a pair of wall lights, one of which is featured in the exhibition.

|

|

|

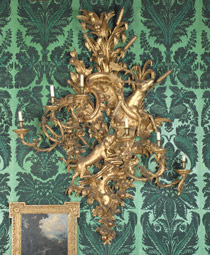

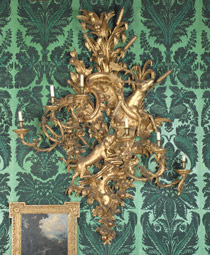

View of the Picture Gallery at Temple Newsam House, with a pair of wall lights (girandoles), one of which is featured in the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

|

Temporarily presenting these works of art outside their usual display contexts offers the unique chance to discover unexpected relationships and exchanges among different artistic practices and to make new visual associations between artworks that are often thought to be fundamentally distinct.

|

|

|

Our perception of an individual work of art as more sculptural, or more decorative, is influenced by many factors, including its setting, material, scale, function, and number.

|

|

|

|

|

Two Putti, probably Flemish, late 1600s. © Leeds Museums & Galleries, photography by Norman Taylor

|

|

Setting

We may perceive works of art differently if we know they were made for, and then removed from, a certain setting.

The original location and function of this pair of carved wooden putti (winged boys) is not known, but we can deduce that they once formed part of an integrated decorative ensemble, perhaps in a church. They are carved completely in the round, appearing to fly. Pinholes in the palms of their hands suggest they once supported—or were suspended from—another element, perhaps the carved swags of a garland, drapery, or crown.

Removed from their original context, the putti now stand as sculptural objects in their own right.

|

|

|

|

Venus (left) and Mars (right), attributed to Filippo Parodi, late 1600s. © Leeds Museums & Galleries, photography by Norman Taylor

|

|

|

Material

A medium's solidity, fluidity, permanence, or fragility can also impact our perception of artworks. These marble busts were created by Parodi, a prominent Baroque sculptor who began his career as a woodcarver. They are masterfully carved to create the illusion of soft drapery, skin, and reflective metal.

Another set of busts in the exhibition, representing Louis XV and Marie Leszczynska, are similar in scale and pose but made of lead-glazed earthenware, a fragile material related more to decorative arts than sculpture. The smooth white finish on the surface of each bust works to imitate the qualities of marble.

|

|

|

Scale

The size of an object can determine its placement, and therefore function. One of the great sculptural programs executed in France during the reign of King Louis XIV comprised 28 large-scale marble figural groups for the gardens of Versailles. At about 42 inches high, this bronze statuette is a half-scale version of the marble sculpture supplied by the artist François Girardon. An albumen silver photograph from about 1870 depicts Girardon's monumental sculpture still in its original outdoor setting. The bronze statuette in this exhibition, however, was intended for indoor display. Its smaller, more intimate scale affects not only its visual impact, but also its function.

This bronze is paired with another scaled reduction from the Versailles commission, a sculpture representing Boreas Abducting Orithyia by Gaspard Marsy. Pedestals for these bronzes by André-Charles Boulle are themselves elaborate works of art, veneered in luxurious materials and fitted with gilt-bronze mounts.

Pluto Abducting Proserpine, Boreas Abducting Orithyia, and their pedestals were on view in Taking Shape through June 21, 2009; they are on view in Cast in Bronze: French Sculpture from Renaissance to Revolution from June 30 to September 27, 2009. The quarter-size version of Pluto Abducting Proserpine remains on view in Taking Shape.

|

|

|

Function

One of the key distinctions frequently drawn between sculpture and decorative arts is the latter's association with function. Although the use and utility of an object is sometimes considered a constraint to artistic innovation, it can also be a creative force.

This pair of silver and bronze sugar casters takes the form of two boys carrying bundles of recently harvested cane. They may have been designed to contain sugar that could be funneled into the receptacles of the hollow bundles and shaken out through the piercings. However, because the bronze figures are heavy and their bases are unfinished underneath, the pair may have played an ornamental, rather than functional, purpose.

|

|

|

|

|

Pair of Greyhounds, after a design by Thomas Hope, early 1800s. © Leeds Museums & Galleries, photography by Norman Taylor

|

|

Number

Historically, both fine and applied artists created pairs, sets, suites, or multiples of objects to serve different purposes.

These greyhounds, for instance, appear now as independent works, but they were originally designed as paired fittings for a piece of furniture. They were probably once placed on a classical-style couch installed in the London residence of the Regency collector and designer Thomas Hope. Later separated from the couch when the furniture fell out of fashion, they gained new status as autonomous sculptures of elegance and beauty.

|

|

|

Furnishings were often made to complement overarching decorative schemes. By removing them from their historic or conventional settings, we can begin to appreciate the decorative arts as exceptional sculptural objects that reveal highly creative artistic ingenuity and expression.

|

|

|

|

Wall Light (Girandole), James Pascall, possibly after a design by Matthias Lock, 1745. © Leeds Museums & Galleries, photography by Norman Taylor

|

|

|

The function and form of lighting fixtures often encouraged inventive design solutions to the problem of illuminating large interiors.

This monumental wall light, one of a pair installed in the Picture Gallery at Temple Newsam House, is distinguished by its sculptural quality. Celebrating the hunt, it features virtuoso carving of a hound in pursuit of a stag amid cattails. The hunting theme ties into a 1740s decorative scheme for the gallery linking the ancient pastoral paradise of Arcadia with the woodlands and game park surrounding the house.

The ordinary function of this object—to hold candles—contrasts dramatically with its sculptural magnificence.

|

|

|

|

|

Wall Light with the Herm of Zephyr, French (Paris), about 1700–1715. The J. Paul Getty Museum

|

|

Baroque and Rococo wall lights often featured projecting branches that helped to extend the reach of candlelight into a room. The maker of this wall light made creative use of this feature to create a visual pun playing upon both form and function.

The fluttering wings of Zephyr (Greek god of the gentle west wind and the harbinger of spring) agitate currents of air that cause the fitful flames of the candles he holds to flare and flicker. Just as his breath dispels the last clouds of winter, he also symbolically blows away the darkness of the room.

|

|

|

|

Candlestand, attributed to Edward Griffiths after a design by Thomas Johnson about 1760. © Leeds Museums & Galleries, photography by Norman Taylor

|

|

|

One of a set of four, this candlestand is an extraordinary virtuoso piece of carving and design. The naturalistic candle branches are carved as gnarled and twisting twigs, and the stylized entwined dolphins have fierce red eyes and armorlike scales.

Stalactites and stalagmites (mineral deposits) on the candlestand's base evoke a rustic, watery grotto in the park of the estate for which it was created, Hagley Hall in Worcestershire, England. The surface tones imitate rich mahogany, green leaves, and shimmering crystals.

|

|

|

|

|

Mirror (Pier Glass), English, mid-1700s or about 1800–1850. © Leeds Museums & Galleries, photography by Norman Taylor

|

|

The frame of this mirror presents a detached dragon hovering menacingly over two fantastic birds.

The design innovatively combines asymmetrical scrolls and leafy decoration with the mythical creatures of chinoiserie (Chinese-inspired motifs) to create a composition with a sense of movement and drama.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The decorative capacity of sculpture and the sculptural inventiveness of the decorative arts are brought to bear on this object, a gilt-wood side table by Johann Paul Schor.

A sculptural tour de force, it defies any straightforward association with practical function and highlights the fluidity between form and function, sculpture and furniture. Moreover, it reconfigures the ideas and roles we often associate with the decorative arts to reveal the inventive expression of an imagination unfettered by convention.

|

|