Rubens

Picturing Antiquity

The Inspiration of Antiquity

During eight years in Italy (1600–1608), Rubens avidly studied a variety of ancient marble sculptures and reliefs in Mantua and Rome. He responded to the narrative focus and drama created by the dense figural compositions on sarcophagus panels, such as the relief depicting Meleager’s hunt for the ferocious Calydonian boar, displayed here. The close correspondence between Rubens’s oil sketch and the sarcophagus panel strongly suggests that he was familiar with the ancient scene. The two works, united in this exhibition for the first time, provide a vivid example of Rubens’s transformation of ancient sculpture.

Rubens in Italy

In 1600 the twenty-three-year-old Peter Paul Rubens traveled from his native Antwerp to Italy, and was soon employed as court artist by Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua. He spent the next eight years in Italy studying firsthand the works of Raphael, Titian, Michelangelo, and Correggio, among other Renaissance masters, as well as ancient art.

During two periods spent in Rome (1601–2 and 1606–8), he gained access to important private collections of antiquities, thanks to negotiations by his elder brother, Philip, who arrived in Rome to study law in 1601. This immersive experience had a profound impact on Rubens’s art. Self-Portrait with a Group of Friends in Mantua, his earliest self-portrait, attests to the camaraderie Rubens and his brother found among a circle of scholars and artists devoted to the ideals of classical antiquity.

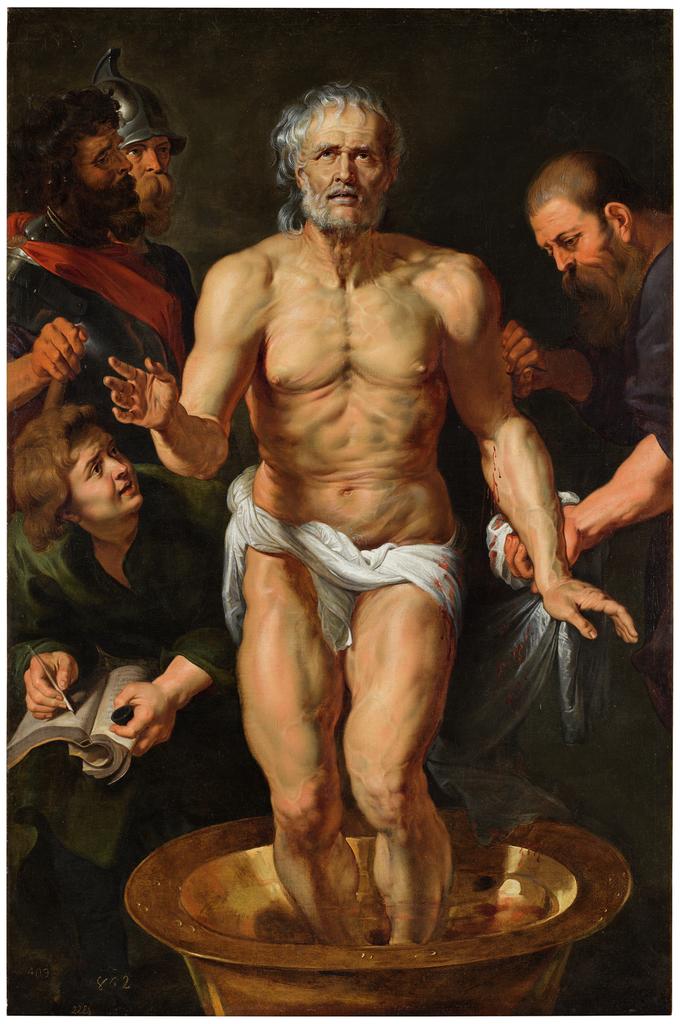

Seneca: Philosopher and Model of Virtue

In 1605 the famed Flemish scholar Justus Lipsius (1547–1606) published an important edition of the works of the Roman philosopher Seneca (about 4 BC–AD 65). Reprintings in 1615 and later include engravings after drawings by Rubens. Lipsius was the principal exponent of Neo-Stoicism, the revival of the Stoic philosophy embraced by Seneca, recast in a form that would be acceptable to Christians.

Apart from his scholarly objectives, Lipsius sought to promote Stoicism as a model for human behavior that emphasized self-control and fortitude to overcome destructive emotions. Seneca himself was venerated for exemplary courage in the face of death. In their own lives, Peter Paul Rubens and his brother Philip adopted many of the tenets of Neo-Stoicism advocated by Lipsius, a philosophy that provided comfort to those who faced perpetual danger during decades of war between Catholics and Protestants.

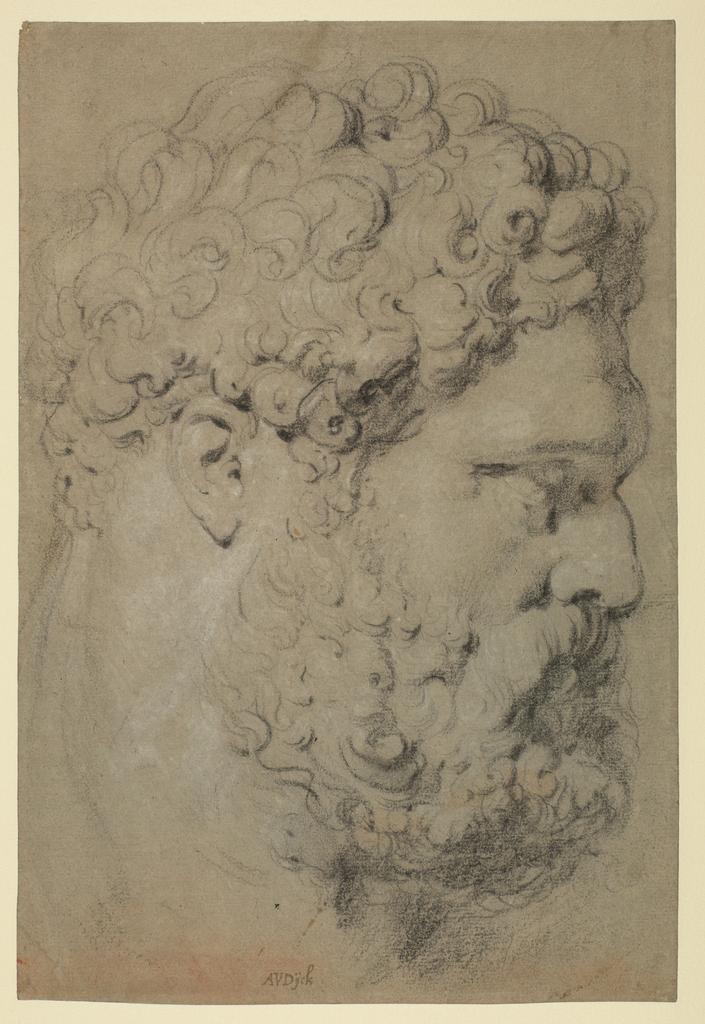

Drawing After Classical Sculpture

Beginning in the Renaissance, young artists learned to represent the human figure by studying classical sculpture as well as live models. Through this process they assimilated a rich vocabulary of poses, gestures, and expressions.

Rubens took an innovative approach in drawing after classical sources. He studied individual sculptures over and over again, copying them from many and often unusual points of view, with painstaking attention to both their overall composition and specific details. Rubens cautioned young artists to focus on the form and not the materials of statues, to avoid “the smell of stone” in their drawings and paintings. He sought to convey a sense of flesh and blood in these figures, depicting them with dynamism, pathos, and drama. These qualities became the distinguishing traits of Rubens’s own art.

The Farnese Hercules

The celebrated statue known as the Farnese Hercules, depicting the hero at rest after his twelve labors, was discovered in 1546 during excavations sponsored by Pope Paul III (ruled 1534–1549). Over three meters tall, with striking musculature, and signed by the Greek sculptor Glykon, the statue became a highlight of the Roman tour for visiting scholars, connoisseurs, and artists. Its colossal size and prestigious placement in the courtyard of the Farnese Palace ensured its stature as one of the most studied and copied statues in Rome. For Rubens, the robust, muscular, broad-shouldered torso epitomized the perfect male body. He first encountered the figure as a youth in Antwerp through prints or reproductions such as those by Goltzius and Tetrode. Once in Rome, he studied the actual marble from all sides, making separate drawings of the arms, legs, and head.

Rubens, Peiresc, and the Study of Ancient Coins and Gems

Like many of his friends in Antwerp and Leiden who were educated in classical subjects, Rubens was an avid collector of ancient Greek and Roman coins. The imagery on coins provided scholars with a wealth of information: portraits of rulers, depictions of deities and mythological scenes, and representations of historical events. Inspired by these images, Rubens reinterpreted them for his own compositions. Rubens was also fascinated by engraved gems and cameos. Each was a unique work, carved by hand, and thus rarer and more valuable than a coin. In 1621, a much-respected French scholar, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Periesc (1580–1637), contacted Rubens with news of the discovery in Paris of a spectacular cameo with a complex scene showing the deified Roman emperor Augustus and the imperial family. (Rubens’s painting of the cameo, known as the Gemma Tiberiana, and an engraving based on drawings of it are displayed adjacent). The two scholars planned an illustrated “Gem Book” on the most important cameos in Europe. Although a number of engravings were prepared, the projects unfortunately never saw publication.

Visualizing Victory: The Imagery of Triumph

In ancient Rome, the celebrations of imperial military victories were commemorated in carved reliefs on triumphal arches and columns. Depictions of processions and the arrival of the victor at the city gate combined real and allegorical figures. Such scenes offered a wealth of historical detail, including armor, trophies, and quadrigae, the splendid four-horse chariots. The extraordinary carved agate cameo known as the Gemma Constantiniana, which Rubens studied closely, was itself a commemorative trophy.

Rubens recognized the propagandistic nature of these spectacles, freely adapting their formal language to create imagery capable of communicating complex political themes. The elaborate designs he made for Antwerp’s 1635 rendition of an ancient triumphal entry were the most ambitious and eloquent expressions of his deep knowledge of the political theater of the classical past.

Antwerp’s Triumphal Entry

In 1635 the city of Antwerp staged a triumphal entry to honor the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, Philip IV’s nephew, who was the Catholic victor over Protestant forces at Nödlingen. Rubens devised this ambitious urban festival with two humanist friends, the city secretary Gevartius and the former mayor, Nicolaas Rockox. Temporary structures erected along the procession route included nine double-sided triumphal arches with paintings and decorations to be executed by numerous artists following Rubens’s designs. The lavish volume commemorating the event, is shown open to the illustration of the arch celebrating the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand

In late 1634, Rubens declared to his friend Peiresc: “I am so overburdened with the preparations for the triumphal entry for the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand …that I have time neither to live nor to write….The magistrates of this city have laid upon my shoulders the entire burden of this festival, and I believe you would not be displeased by the invention and variety of subjects, the novelty of the designs, and the fitness of their application.”

Rubens and Mythology

Ancient stories about the lives and loves of the gods supplied Rubens with stimulating subjects for painting. He read classical texts in their original languages, beginning as a schoolboy with Ovid’s Metamorphoses in Latin and Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans in Greek. He must have known many works by heart. In his paintings Rubens synthesized these familiar literary sources and incorporated overt references to ancient sculpture to convey his highly individual version of a living classical past.

Rubens’s erudition spurred him to portray unusual episodes from mythology that intrigued learned viewers. He developed evocative compositions of deities hunting and carousing, images that proved especially popular with his audience. Rubens’s portrayals of life in primeval Arcadia take place in beautiful landscapes populated by virtuous nymphs and lecherous satyrs. And empathetic interpreter of classical poetry, he ascribed relatable emotions to his characters, including the gods. Rubens explored broader philosophical topics in his mythological paintings as well, such as Nature’s abundance and transformative power of love. To create especially vivid scenes, he chose large formats and collaborated with colleagues in Antwerp, incorporating their distinctive style of rendering animals and still life.