Michelangelo: Mind of the Master

Sculptor. Painter. Architect.

Michelangelo Buonarroti is recognized as one of the most creative and influential artists in the history of Western art. His most celebrated creations have become icons of world culture: the monumental marble David in Florence; the astonishing frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and the soaring dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica, both in Rome.

Michelangelo was active mainly in Florence and Rome, two major cultural and political centers in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe. He received the support of important patrons, including members of the ruling Medici family of Florence and, for a crucial decade, the leader of the Roman Catholic Church, Julius II. His creations were revered and coveted particularly for their ingenious compositions and their powerful representation of the muscular human body.

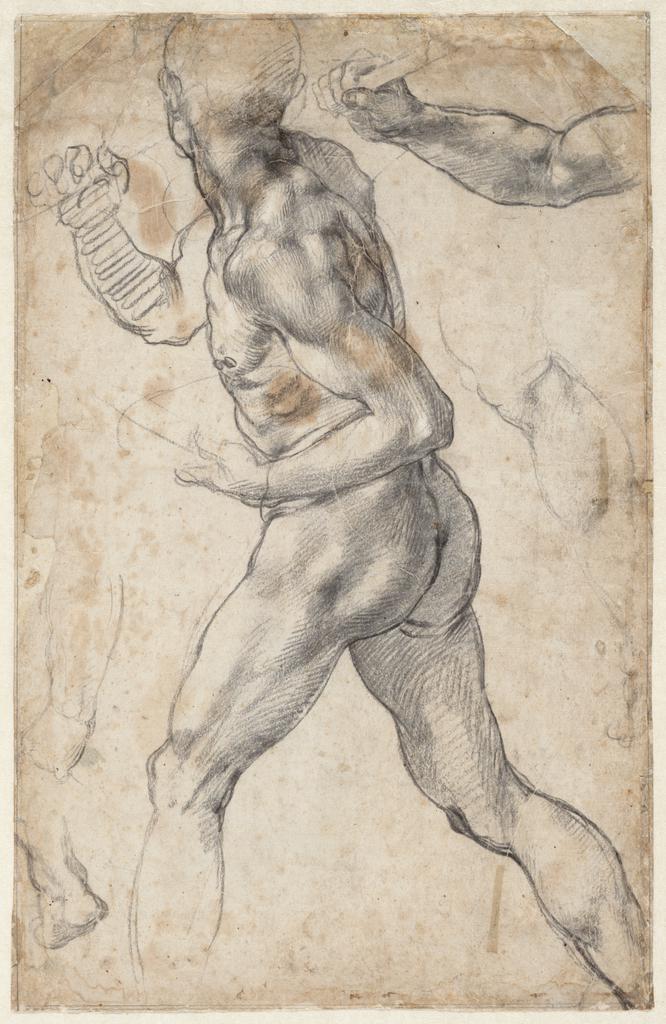

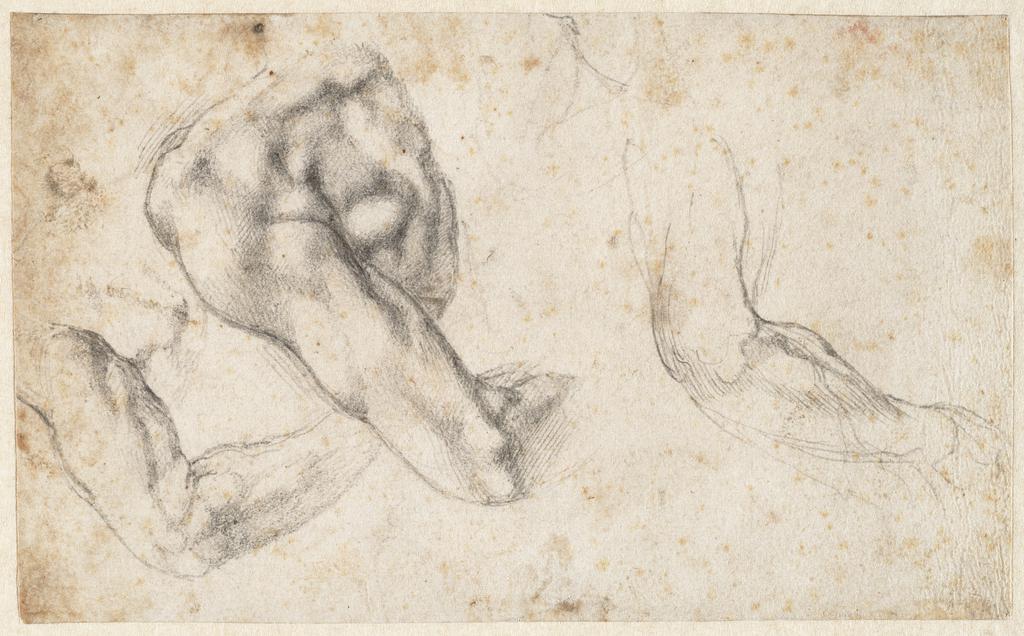

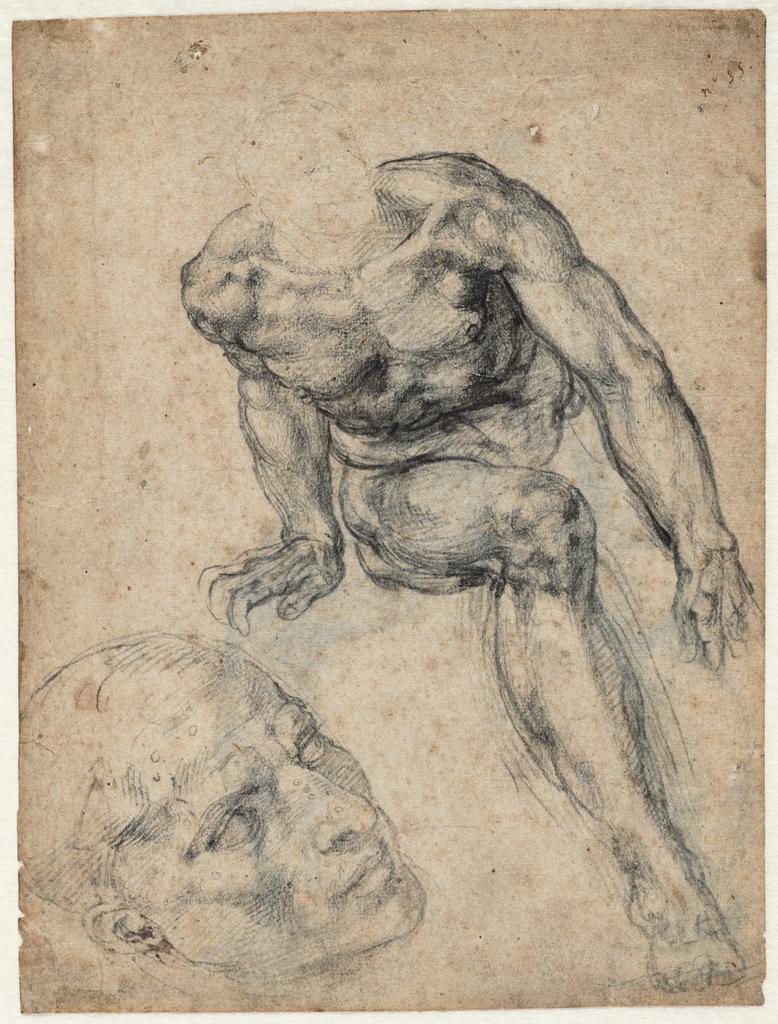

Drawing was key to Michelangelo’s practice. This exhibition explores the full range of his work through a selection of his rare preparatory drawings, from compositional sketches to detailed figure studies. The works span the arc of Michelangelo’s long life—he died at the age of eighty-eight—and give unparalleled insight into his artistic invention and achievements.

Michelangelo and His Drawings

For Michelangelo, drawing was a fundamental, lifelong activity. When he was a student, it helped him learn from other artists’ work; thereafter drawing was a tool he used to capture reality and the conceptions of his imagination. Consistently dedicated to drawing the human figure from life, a growing practice in Florentine artists’ studios at the time, Michelangelo took this to a new level of verisimilitude through keen observation, as well as by studying dissected

corpses to better understand the underlying muscles.

Early in his career Michelangelo drew mainly in pen and ink, but he soon came to appreciate the convenience and effectiveness of naturally mined chalk. He used both red and black colors, preferring the latter as time went on.

Today, as through history, Michelangelo’s drawings are valued not only as works exhibiting extraordinary skill but as windows into the mind of the master. They let us witness—in an astonishingly direct and intimate way—the creation of some of the greatest works of Renaissance art.

The Battle of Cascina

In the summer of 1504, Michelangelo was commissioned to paint the Battle of Cascina on one wall of the Sala del Gran Consiglio (Great Council Chamber) in the Palazzo della Signoria, Florence. The commission brought Michelangelo into direct competition with Leonardo da Vinci, who had been contracted to paint the Battle of Anghiari on the opposite wall a year earlier. Both murals would commemorate famous battles in Florentine history. Although the artists made full-scale drawings (called "cartoons") of parts of their compositions, the works themselves were never completed. The large cartoons, celebrated and constantly studied, eventually fell apart from handling by overzealous copyists.

The copy of Michelangelo’s cartoon by Bastiano da Sangallo, reproduced here, records the composition with its life-size figures. For his scene Michelangelo focused the action on a moment before the battle when Florentine soldiers were surprised by enemy forces as they bathed in the river Arno. The idea played to Michelangelo’s strength in rendering the human figure and cemented his role as the prime pioneering draftsman of the heroic male nude. Two rare surviving preparatory drawings for Michelangelo’s famed cartoon are shown nearby; these were revolutionary for the period in their relatively large scale and naturalistic precision.

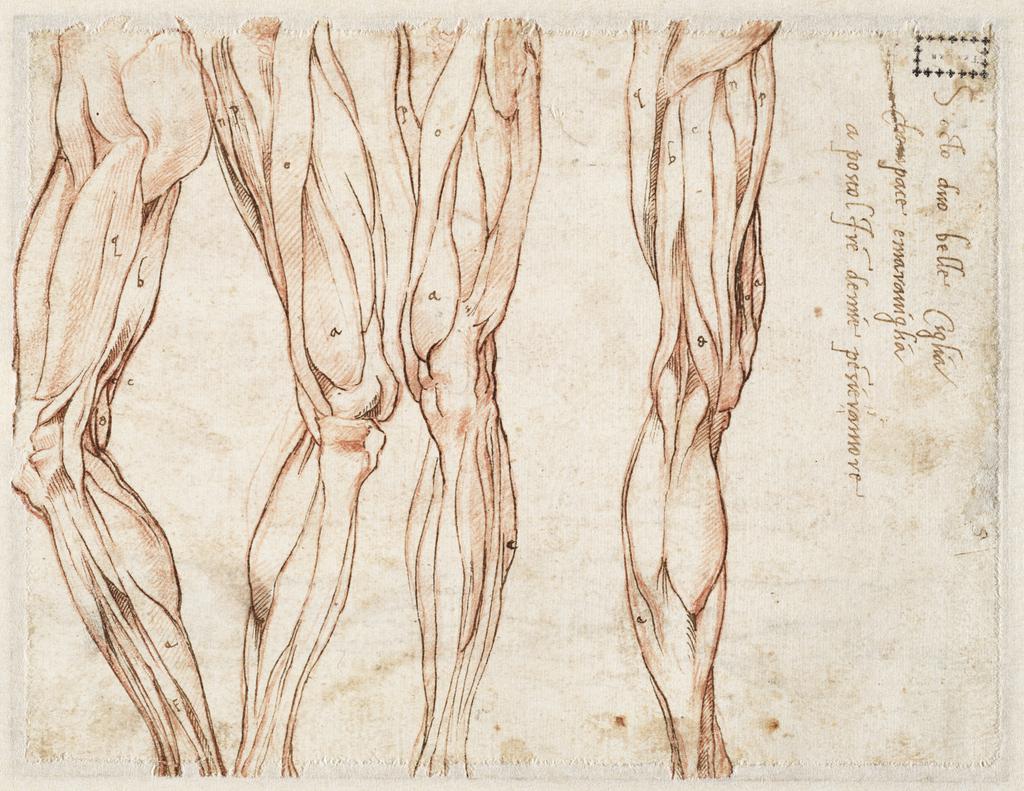

Michelangelo and Anatomy

Unlike most Renaissance artists, who learned about the human body from ancient sculpture and live models, Michelangelo participated in dissections. According to his acquaintance and biographer Ascanio Condivi, the artist first examined corpses in the convent of Santo Spirito in Florence when he was in his late teens.

Michelangelo’s interest in anatomy did not extend to the organs but focused on the muscles and bones. His surviving anatomical drawings, like the ones exhibited here, attest to his thorough understanding of certain muscles, especially those of the limbs. The dissections enabled Michelangelo to grasp how the surface and contour of the body change when one moves. This knowledge was crucial for the creation of his renowned heroic nudes.

San Lorenzo, Florence

During the 1510s and 1520s the ruling Medici family of Florence sought Michelangelo’s talents to aggrandize themselves and commemorate their power and legacy. Two Medici popes—Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici) and Clement VII (Giulio de’ Medici)—provided Michelangelo with commissions centered on the family’s parish church, the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence. Michelangelo designed the architectural and sculptural elements for a New Sacristy, housing tombs of family members, and for the Laurentian Library (named for Lorenzo de’ Medici), adjacent to the church. The tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours was to be adorned with reclining statues representing Night and Day. Very few of Michelangelo’s drawings for sculpture survive, but four sheets related to Day offer rare insight into Michelangelo’s careful preparations on paper before taking his chisel to the marble block.

Two and Three Dimensions

In his artistic practice, Michelangelo used drawings for designing both two- and three-dimensional objects. But he approached his task differently when working toward a painting rather than a sculpture or an architectural structure.

In the case of two-dimensional projects, Michelangelo relied exclusively on drawings in the design process. He worked out the composition through a sequence of sketches and studies. After he finalized the design, he transferred it with the help of a cartoon, a full-scale pricked drawing. In the case of three-dimensional projects, drawings allowed him to explore only one

view at a time. Therefore, Michelangelo often drew the same form from various angles and introduced models made of clay, wax, or wood into his process, which enabled him to test his ideas in space.

The Sistine Chapel Ceiling

The Sistine Chapel was constructed between 1473 and 1481 for Pope Sixtus IV as the pope’s private chapel. It has served as the site for important papal ceremonies and the meeting place of the Sacred College of Cardinals.

The dazzling complexity, beauty, and achievement of Michelangelo’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome still astonish visitors more than five hundred years after they were painted. The project took Michelangelo just four years— remarkable given that it comprised over 5,700 square feet of labor-intensive fresco painting, all completed by the artist himself, with only the most menial of preparatory tasks delegated to assistants.

The commission to paint scenes from the biblical book of Genesis came from Pope Julius II in April–May 1508. The numerous illusionistic compartments also included alternating prophets and sybils (female prophets). Prominent images of athletic male nudes (ignudi) flank the principal narrative panels. Michelangelo worked standing up, his brush held above his head, paint and debris falling into his face. He relied on lamps since scaffolding blocked much of

the natural light from the windows.

Michelangelo completed the commission in two sessions. When the scaffolding from the first half was taken down in the summer of 1511, he had a chance to see the result from the floor, and in the speedily completed second half (toward the altar) he made the figures larger

and the compositions clearer.

The drawings for the Sistine Ceiling shown here are among the few that survive. Michelangelo burned the vast majority so that no one, according to the artist-biographer Giorgio Vasari, could see his creative struggles.

The Last Judgment

In 1533 Michelangelo received a second commission for the Sistine Chapel, this time from Pope Clement VII: a huge fresco of the Last Judgment above the altar. The artist completed it in 1541. Although the Last Judgment was a standard subject in Christian iconography, showing the moment in Christian belief when God sits in judgment of humankind, Michelangelo’s version was unorthodox. A bare-chested Christ presides in the middle of the composition, surrounded by mostly nude saints, while the saved rise to heaven and the damned descend to hell. The pervasive nudity caused immediate controversy within the Catholic Church, and in 1563 orders were given to cover some of the exposed flesh with carefully placed drapery. Daniele da Volterra did the overpainting in 1565, soon after Michelangelo’s death. Nevertheless, Michelangelo’s lifelong focus on the depiction of the human body reached its zenith in the Last Judgment, and the fresco was revered by later generations of artists.

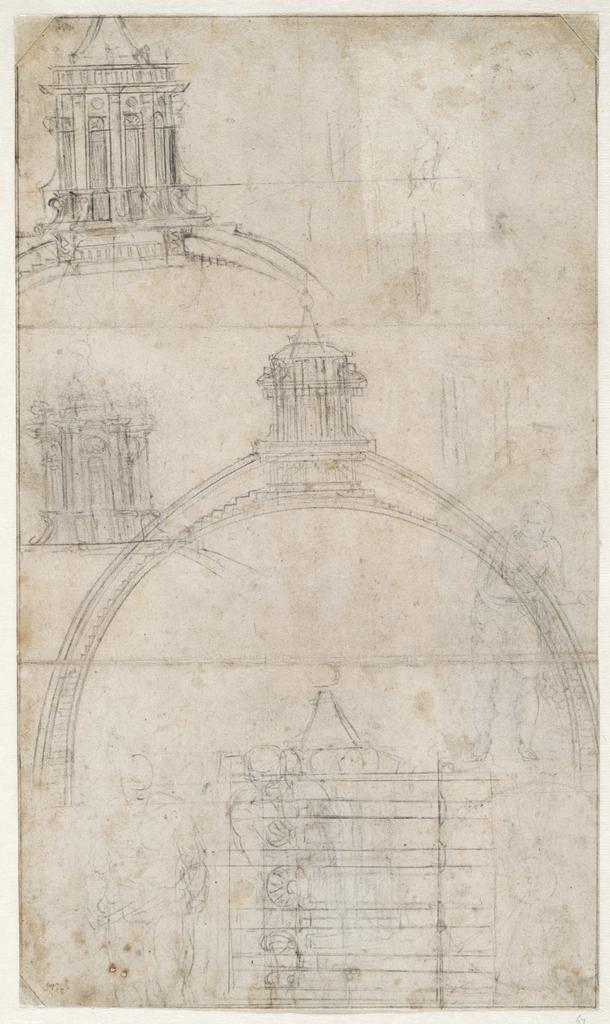

Michelangelo and the New Saint Peter’s Basilica

Following the death of the architect Antonio da Sangallo in 1546, Pope Paul III put Michelangelo in charge of construction of the new Saint Peter’s Basilica, the seat of the Roman Catholic Church. The pope entrusted the artist with this highly prestigious project despite his limited experience as an architect.

The principal challenge that Michelangelo faced was designing a grand dome over the church crossing (where the transept intersects the nave). He employed both drawings and three-dimensional models to explore his ideas and convey them to others. Because of the project’s magnitude and complexity, Michelangelo did not live to see the finished dome; only the drum was near completion when he died in 1564.

Destruction, Survival, Appreciation

Protective of his ideas and deeply distrustful of even those close to him, Michelangelo burned large quantities of his drawings over the course of his life. When he died in Rome on February 18, 1564, just five figure drawings and five architectural sheets were found in his home, locked in a walnut chest protected with wax seals. More remained at his house in Florence, but they were still only a fraction of those he produced. It has been estimated that if Michelangelo drew just a single sheet every day of his long working life, he would have made about twenty-eight thousand drawings. We currently know of only about six hundred. A group of the very finest is on display here now.