|

|

|

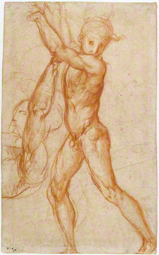

Nude Warrior Leaning on a Volute, about 1589–1602, Toussaint Dubreuil

|

|

Contorted, elongated forms and dramatically animated compositions characterize the emerging artistic style of the late Renaissance (about 1520–1600). Concerned with grace and virtuosity in the depiction of the human figure, this new style is best identified with the rise of the Italian concept of disegno, referring not only to the physical act of drawing but also to the essence of creative design.

This exhibition explores the various radical iterations of the style from its origins in Florence across Europe, featuring rare drawings from the J. Paul Getty Museum's collection by Italian, French, and Netherlandish artists, together with five works from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

A naked male figure bursts with energy in this drawing by the French artist Toussaint Dubreuil. He is perhaps Mars, the Roman god of war, with plumed helmet and staff, leaning on a voluted column capital. After sketching the form in black chalk, Dubreuil modeled the volumes with vigorous parallel- and cross-hatched, curvilinear pen-and-ink lines, creating a powerful sculptural quality.

|

|

|

Florentine artists such as Jacopo Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, and Giorgio Vasari were at the forefront of the new style that reflected disegno, as they combined energy with elegance, approaching traditional motifs with a novel playfulness. In 1568, Vasari wrote that disegno, in the sense of "drawing," was the father of the three arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. Yet he also emphasized that the term should also encompass the concept and spark of creation—it was "the animating principal of all creative processes." Several decades later, with some clever wordplay, Federico Zuccaro used disegno as evidence that all artistic design was divinely inspired: It was the segno di Dio (sign of God).

Jacopo Pontormo's creative process took place directly on paper in a frenzy of drawing. In the Male Nude he captured the motion and dramatic pose of a young model in a rapid succession of bold strokes. The shadow on the back of the model's left side is conveyed through its reinforced outline. Such studies of figures from life formed the basis for the characters in Pontormo's paintings, which sometimes became exaggerated assemblages.

|

|

|

In this drawing by Giovanni Battista Naldini, the biblical miracle of a son brought back to life is conveyed by powerful, iconic gestures. Florentine art of the period was dominated by such turbulent yet studied compositions. The image seems to drip with the dense media of fluid wash and thick white highlights, but the complex decorative treatment is at odds with the speed with which it was made.

Naldini created the drawing in preparation for an altarpiece that he painted for the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, which was later destroyed by a fire in 1771.

|

|

|

King François I of France was a major patron of the arts, and the group of artists he assembled at the Château de Fontainebleau, about 35 miles southeast of Paris, worked in a variety of media, including painting, sculpture, printmaking, the decorative arts, and plasterwork. Principal among the artists were Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio, who took over the workshop after Rosso's suicide in 1540.

The artists who worked at Fontainebleau also created elaborate costumes for lavish masquerades. At such an event in February 1542, François I assumed the guise of a centaur. This drawing presents a design for his costume, and includes color notes such as bleu (blue) on the flying drapery at right. According to written accounts, a mechanism in the horse made its hind legs move in conjunction with the king's, and the Lapith woman on its back was made of papier-mâché.

|

|

|

|

|

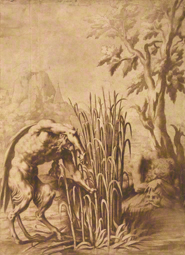

Pan Cutting Reeds, about 1550, Unknown artist

|

|

The loves of Pan, the Greek god of woods and fields, were often depicted by artists during the late Renaissance in France. In the myth, Pan was pursuing a nymph named Syrinx when they reached a river that blocked her escape. To avoid Pan's advances, she turned into a reed plant. The sound of the wind blowing through the reeds pleased Pan so much that he cut them to make a set of pipes, as depicted in this drawing by an artist from the School of Fontainebleau.

In the late 1500s, the Château de Fontainebleau was abandoned due to the Wars of Religion, but in 1594 King Henri IV began renovations, sparking the second School of Fontainebleau with artists such as Toussaint Dubreuil, whose work appears at the top of this page.

|

|

|

Without a king or court culture to patronize the arts in the Netherlands during the late 1500s, works—mainly prints—were created for a wider portion of the population.

Dutch artists continued the Renaissance tradition of masking erotic and risqué subject matter behind the pretense of mythological and allegorical scenes, as reflected in this drawing. In a scene from Homer's epic poem The Odyssey, Vulcan, having discovered that his wife Venus has been sleeping with Mars, holds a chain net he forged to trap the deceitful pair and expose them to the ridicule of the other gods.

With its ornate composition of figures arranged in complex, artificial poses, this drawing by Hendrick Goltzius reflects the exaggerated style of the Prague-school artist Bartholomaeus Spranger, who was a major influence on Dutch art. Spranger's style is also captured in the engraving Cupid Discovering Psyche in His Bed, one of five loans from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art included in the exhibition, which depicts a lost wax relief by Spranger.

|

|

|

|

|

Charity, Gratitude, and Ingratitude, about 1594, Cornelis Ketel

|

|

One of only six known drawings by Cornelis Ketel, this design was created for the central section of a famous print The Mirror of Virtue. The allegorical figure of Charity sits between Gratitude and Ingratitude. At right, Gratitude receives the moon, and her eternal appreciation is confirmed by the obelisk behind her—a memorial object representing permanence. In contrast, Ingratitude, who is receiving the sun, bites Charity's arm and stabs her. Ingratitude's pernicious nature and short-lived memory are further emphasized by the feuding snakes, wrapped around his thigh, and the skull on which he rests his left knee. Charity is accompanied by symbols of kindness and generosity—a lion, a dog, and a tiny mouse attempting to chew through the rope around the lion.

|

|