A Nation Emerges: 65 Years of Photography in Mexico

Photographs of Mexico from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century from the special collections of the Getty Research Institute

Created 2000, updated 2001 and 2010

Author: Beth Ann Guynn, Senior Collections Cataloger

Created 2000, updated 2001 and 2010

Author: Beth Ann Guynn, Senior Collections Cataloger

Search Related Materials

To search the digitized collection select "View Digitized Works" at the top of the page. Use keywords for events such as Decena Trágica, subjects such as revolutionaries, Aztec calendar, and colonial architecture, geographical locations such as Querétaro, and the names of photographers or historical figures.

Introduction

|

|

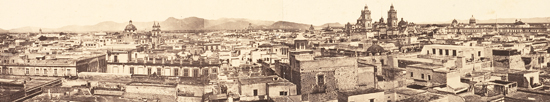

A Nation Emerges: Sixty-five Years of Photography in Mexico represents the work of 30 known Mexican, European, and American photographers, as well as that of anonymous photographers, with over 600 images. Photographic formats include albumen, collodion, and gelatin silver prints, carte-de-visite, cabinet cards, photo albums, and postcards. The earliest images in the site were made in 1857, the same year that Benito Juárez was appointed acting president of the Republic of Mexico. However, the majority span the period from the beginning of the French Intervention in the early 1860s to the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920. This tumultuous and dynamic period in the history of Mexico coincided with rapid developments in the new field of photography. This resource provides a case study of how quickly photography came to be an indispensable

means of documenting, recording, and disseminating multiple views of history.

|

|

Although the first photographs made in Mexico appeared barely six months after the invention of the daguerreotype had been announced in 1839, it was the years of the French Intervention (1864–1867) that saw the burgeoning of photography in Mexico. Tied to the protocol of the court of Maximilian and the official documentation of political events, photographs served to legitimize the emperor. The court brought the European carte-de-visite craze to Mexico, and portraits of Emperor Maximilian, Empress Carlotta, General Bazaine, and members of the court and its Mexican supporters circulated widely in Mexico and abroad. François

Aubert, the official court photographer, made images of the court at play, during ceremonial occasions, and during war, following Maximilian up to his last moments.

|

|

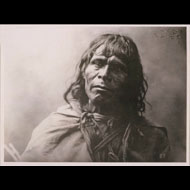

Other early photographers focused on travel and exploration. Foreign photographers in particular were interested in documenting the ethnographic, archaeological, and natural sights of Mexico. Their interest came out of a "rediscovery" of the Americas, initially a romanticized return to pre-Conquest lands, wild and untamed in comparison to archaeological sites in Europe and the Middle East. Désiré Charnay, who began his archaeological explorations in 1858, was the first of the archaeologist-explorers to break with the romanticized conception of ancient Mexico and use the camera as an instrument for scientific research.

|

|

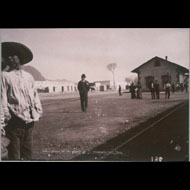

The Mexican government and private entrepreneurs alike also used photography to promote Mexico. Focusing their lenses on the future rather than the past, photographers such as William Henry Jackson, Charles B. Waite, Abel Briquet, and Guillermo Kahlo photographed progress. Their images of landscapes in transition made during a long period of relative political stability show a Mexico being transformed by engineering projects such as telephone lines, tunnels, railroads, bridges, and dams. Their work also memorialized the achievements of the ambitious Porfirian government (1884–1910), and highlighted natural resources in order to attract foreign investors. Photographers such as Agustín Victor Casasola and Kahlo were always on hand to document ceremonial occasions, such as the dedication of buildings and public works.

|

|

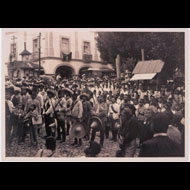

In 1896 Rafael Reyes Spíndola, owner of several newspapers, began to print photographs in his papers. As Mexico moved determinedly into the 20th century, photojournalism rapidly developed as a means both to record change and keep the public abreast of events. By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, the tool that the Porfirian government had used so successfully to document its apogee was instead focused on its demise. The collapse of the Porfiriato and the ensuing years of revolution were extensively chronicled by Mexican, American, and European photojournalists who covered the ever-changing field of action across the country. Revolutionary leaders were quick to seize opportunities to publicize their causes via news photographs, postcards, and even motion pictures. Many images of the revolution expose the brutality and violence of war, and, indeed, are the precursors of contemporary war photography. While most foreign photographers had long since left to cover the western front of Europe, a local photographer, inheritor of the legacy of the Mexican Revolution, was on hand to record the assassination of Pancho Villa in 1923, three years after peace had been restored to Mexico and the infamous revolutionary had retired to his ranch.