Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics

Text by Naoko Takahatake, Christina Aube, Lauren Graber, and Alina Samsonija

Introduction

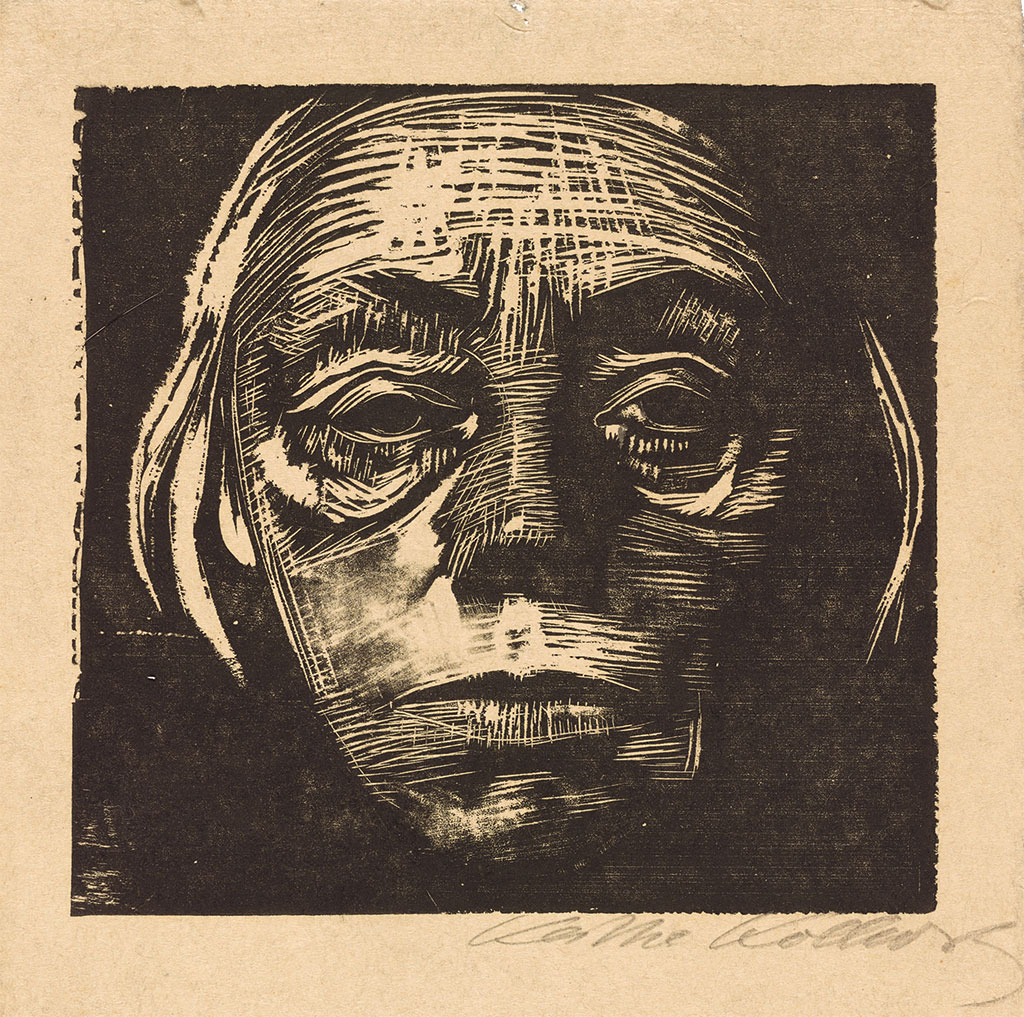

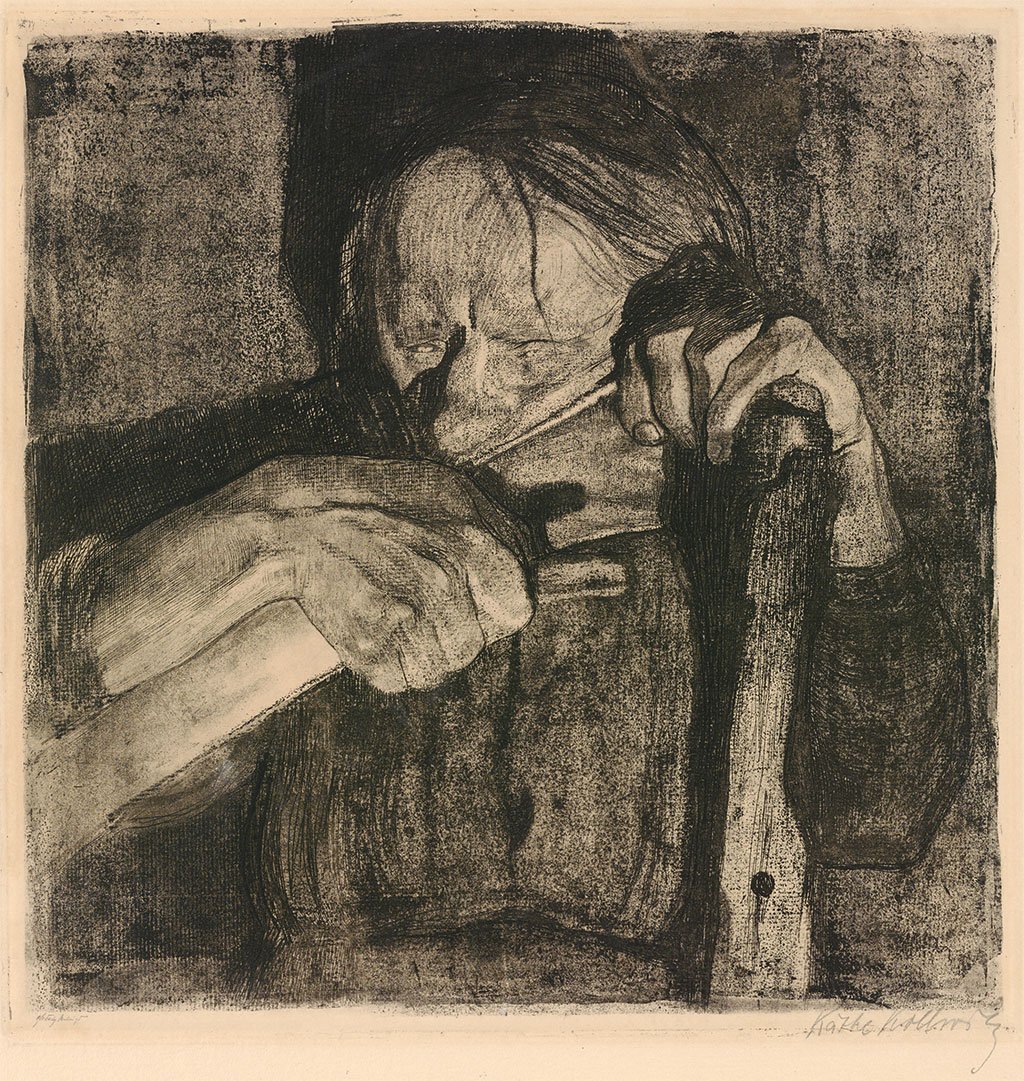

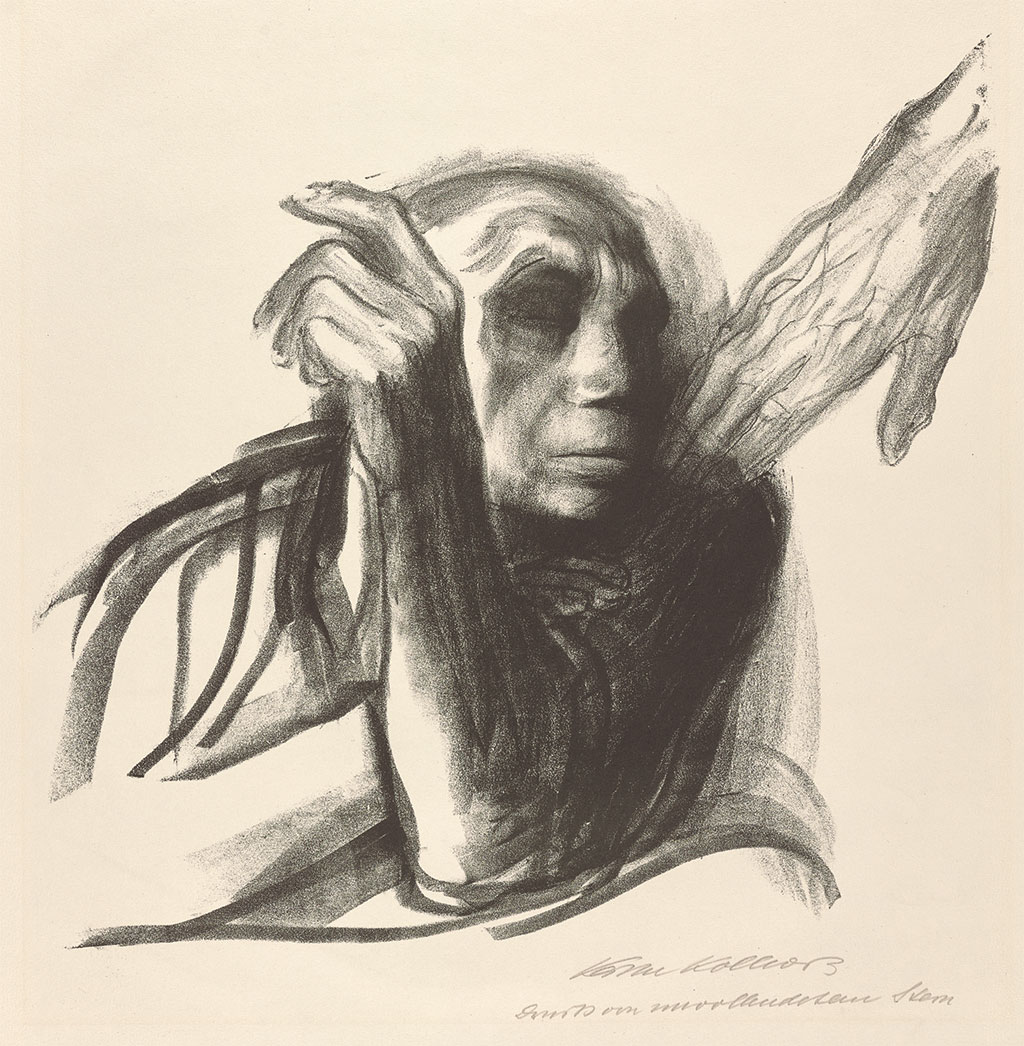

The art of German printmaker, sculptor, and teacher Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) bears witness to experiences of poverty, injustice, and loss in a society troubled by turbulent political change and devastated by two world wars. Spanning all five decades of her career, Kollwitz's prodigious graphic work—notable for its affecting imagery and technical virtuosity—asserts her commitment to social advocacy and her pursuit of artistic excellence.

Kollwitz's reputation flourished during a printmaking renaissance in late 19th- and early 20th-century Germany. The artist embraced the print's capacity to disseminate her designs to a wide audience. As she explored the formal and expressive possibilities of different processes, Kollwitz generated numerous preparatory sheets, including drawings, trial prints, and working proofs. These rich sequences of images vividly document the evolution of her ideas, both artistic and political.

All works in the exhibition are from the Getty Research Institute's Dr. Richard A. Simms Collection of Prints and Drawings by Käthe Kollwitz and Other Artists, which is a partial gift of Dr. Richard A. Simms.

Käthe Kollwitz

Born Käthe Schmidt in a conservative region of the German Empire, Kollwitz grew up in a politically active Socialist household. She studied painting at schools for women artists in Berlin and Munich in the 1880s, but she did not receive formal instruction in printmaking. Learning from artists, printers, manuals, and her own restless experimentation, she produced a remarkable 275 etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts.

In 1919, Kollwitz became the first woman elected as a full member to the Academy of Arts in Berlin but was forced to resign in 1933, following the Nazi Party's seizure of power. She died at the age of 77 in Moritzburg, near Dresden.

Kollwitz's graphic output responded to the economic and political turmoil that disrupted German society from 1870 until 1945. In her search for a visual language that would appeal to discerning collectors and engage an ever-broadening public, she remained largely independent of avant-garde movements such as expressionism. Kollwitz evolved her early realist style toward a greater simplification of form. While she moved from a descriptive to a more suggestive aesthetic, she never abandoned the human figure.

Dr. Richard A. Simms Collection of Prints and Drawings

The Dr. Richard A. Simms Collection of Prints and Drawings by Käthe Kollwitz and Other Artists, which comprises more than 650 19th- and 20th-century works on paper, was a partial gift to the Getty Research Institute in 2016. After acquiring 121 prints from Kollwitz's estate in 1978, Dr. Simms continued to seek works to chronicle her printmaking career, bringing together exceptional sequences of preparatory sheets. His collection, which expanded to 286 works by Kollwitz, also represents artists in her orbit, including George Grosz, Max Klinger, and Ludwig Meidner.

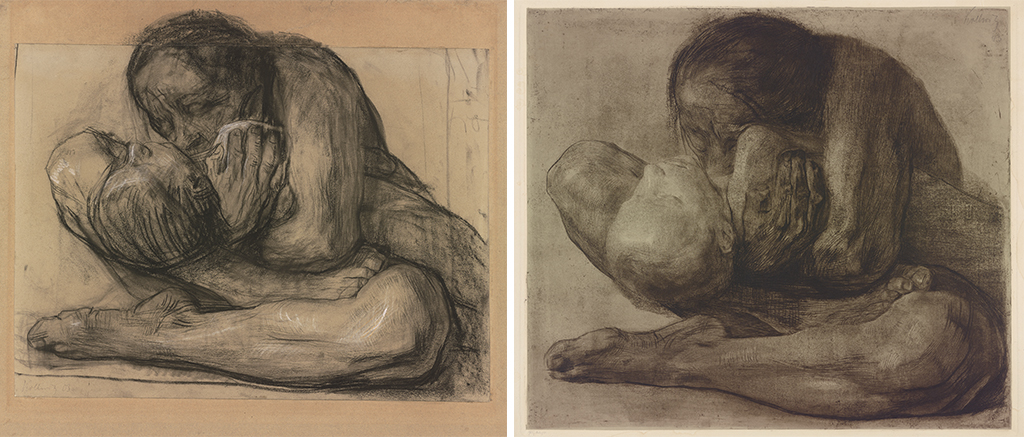

Peasants' War

For its narrative power, scale, and technical complexity, Peasants' War is Kollwitz's most ambitious print cycle. Inspired by historian Wilhelm Zimmermann's book The History of the Great Peasant War (1841–1843), the cycle is a modern interpretation of the German Peasants' War (1522–1525), a popular uprising of laborers against aristocratic landowners. The seven prints in Peasants' War, like those in Kollwitz's earlier series A Weavers' Revolt, evoke the loathsome conditions of modern industrial labor. Both series follow a similar dramatic arc: from provocation to reaction, outbreak of violence, and, ultimately, death and defeat.

The Association for Historic Art—an organization that supported painting and printmaking of German historical subjects—commissioned the series, distributing the prints in 1908. Drawings, trials in lithography and etching, and working proofs produced over the course of six years testify to Kollwitz's meticulous planning and execution. Whereas print series were traditionally uniform in size, Kollwitz varied the dimensions and format of the individual sheets of Peasants' War, strategically framing each scene to amplify its message. The result is a tour de force that affirmed her standing as the foremost woman artist in the German Empire.

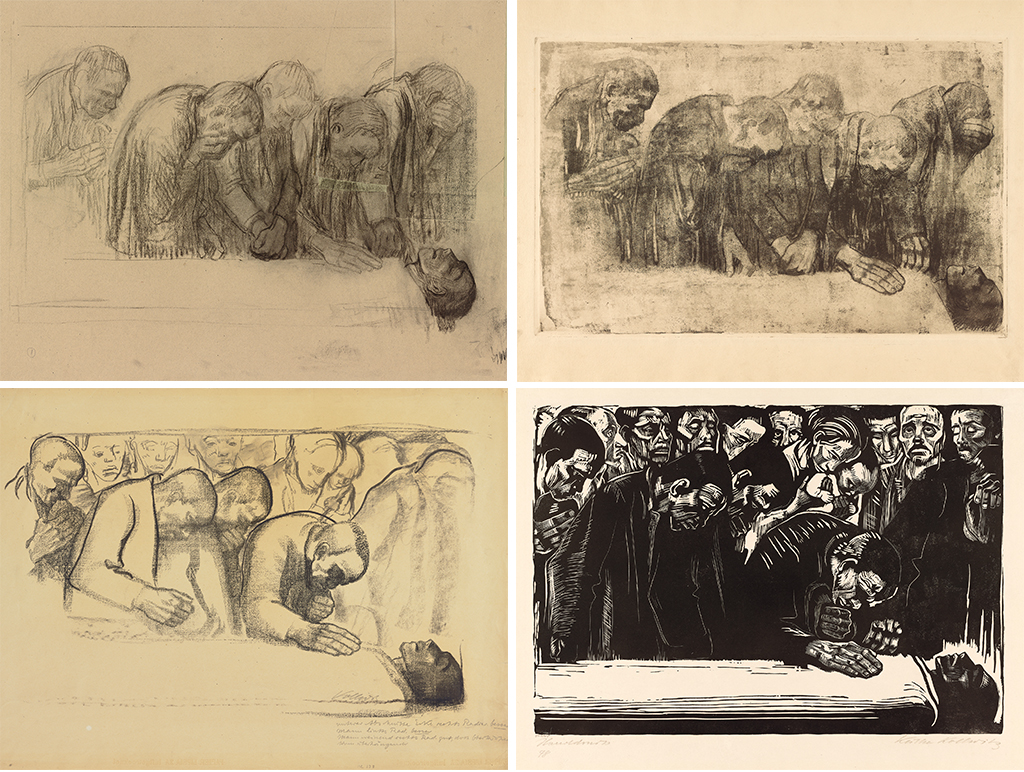

Karl Liebknecht

Following the dissolution of the German Empire and the signing of the armistice agreement to end World War I in November 1918, left and right factions struggled for political power. Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, founders of the Communist Party of Germany, participated in the Spartacist Uprising in Berlin in January 1919. After the provisional government led by the Social Democratic Party brutally suppressed the uprising, Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and murdered by right-wing paramilitary forces. With the Communists in crisis, a coalition of parties established Germany's first democratically elected parliamentary government, known as the Weimar Republic, which lasted until Adolf Hitler ascended to power in 1933.

Although she was not a member of the Communist Party, Kollwitz was moved to create a memorial print for Liebknecht. The artist labored to find the technique that would best express her sentiment, writing: "The immense impression made by the hundred thousand mourners at his grave inspired me to a work. It was begun and discarded as an etching, I made an attempt to do it anew, and rejected it, as a lithograph. And now finally as a woodcut it has found its end."

Kollwitz's Final Years

After 1929, Kollwitz abandoned woodcut and returned to lithography. While the artist made lithographs throughout her career, her approach to the technique evolved as she simplified intricate applications of crayon, brush, pen, scraper, and spatter—at times paired with etching—to more economical crayon and brush works. Her lithographs from 1930 to the early 1940s (when she ceased making prints) were almost exclusively in crayon. In these late works, she often used a transfer method, which entailed drawing on specially prepared paper and relaying the image from sheet to lithographic stone. This turn to a more expedient technique coincided with a rising dedication to sculpture in her last decade.

In 1933, under the Nazi regime, Kollwitz was expelled from the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin and forbidden to exhibit. During World War II, in the late fall of 1943, her Berlin home was bombed and completely destroyed, and numerous works, studio materials, and documents were lost.