9. Engineering a Solution: Latin American Light-Based Kinetic Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Jane Gillies

- Ingrid Seyb

Abstract

The Latin American department at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), began collecting kinetic art in 2004, including works by pioneering artists of the 1960s such as Abraham Palatnik, Horacio García Rossi, Gyula Kosice, Gregorio Vardanega, Martha Boto, and Julio Le Parc. They used various mechanisms—mirrors, the interplay of lights, and bubbling water—to produce movement and create both regular and random patterns. These artworks were displayed in multiple exhibitions, which provided challenges in maintaining their functionality. A recent exhibition, Cosmic Dialogues (2015), brought together the largest number of these works to be shown at one time at the museum, and it provided an opportunity for the conservation department to examine them closely. We addressed questions about the authenticity of the current mechanisms, replacement of components, and the appropriate length of running time. In the past, changes to the works of art were made at the last minute and by anyone who could make them function. This often meant minimal documentation and the use of whatever materials were readily available.

This paper details some of the conservation decisions and treatments made before, during, and after the exhibition, how these affect the longevity and integrity of the works, and where further study is still needed. Where possible through research we identified aspects of their operating processes such as the correct speed, color, and configuration of components. We consider how these works will be maintained in the future, when the supply of original components is exhausted and where defects in the original design, which affect both safe operation and undue wear of components, can be corrected without compromising the outward appearance and authenticity. Whenever possible, we collected information from the artists or their associates as part of the documentation process, but often the details most useful to conservators had been forgotten.

The MFAH is planning permanent display of this collection in a new building (opening 2019), the first permanent galleries of this kind of art in the world, and the work done for Cosmic Dialogues will serve as a pilot program for this complicated undertaking.

The MFAH has been actively acquiring modern and contemporary Latin American art since 2001, partly inspired by the museum’s goal to reflect the diverse population of Houston in its collection. Among the department’s 755 objects, 38 are kinetic and electric works, ranging in date from 1946 to 2010.

The 1950s and 1960s in South America, as elsewhere, was a time of tremendous innovation and change in the art world. European intelligentsia had emigrated in great numbers both before and after World War II, strengthening the already robust cultural ties. Many young artists went to Europe to study, and some stayed permanently (Citation: Rossi 2012:47–67 [Rossi, Cristina. 2012. “Imágenes inestables: Tránsitos Buenos Aires-Paris-Buenos Aires.” In Real/Virtual: Arte cinético argentine en los años sesenta, edited by María José Herrera, 47–67. Buenos Aires: Asociación Amigos del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.]; Citation: Suárez 2007:243–47 [Suárez, Osbel. 2007. “The Logic of Ecstasy.” In Lo[s] cinético[s], edited by Osbel Suárez and Eugenio Fontaneda, 243–47. Madrid: Artes Gráficas Palermo.]). One group of these artists used science and technology as a vehicle for discussing a utopian future (Citation: Ramírez 2004 [Ramírez, Mari Carmen. 2004. “A Highly Topical Utopia: Some Outstanding Features of the Avant-Garde in Latin America.” In Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America, edited by Héctor Olea and Mari Carmen Ramírez, 1–15. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.]). Rejecting the perceived self-centeredness of North American Abstract Expressionism, they de-emphasized the artist as individual and instead focused on the audience, turning spectators into participants with Op Art and kinetic installations (Citation: Popper 1968:150 [Popper, Frank. 1968. Origins and Development of Kinetic Art. London: Studio Vista.]). Many artists made sculptures that were scale models for visionary futuristic architecture (Citation: Popper 1968:139, 192 [Popper, Frank. 1968. Origins and Development of Kinetic Art. London: Studio Vista.]). The Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV), active in Paris from 1960 to 1968, particularly focused on the theme of participation (Citation: Gagneux 2007:14 [Gagneux, Dominique. 2007. “Doit-on entretenir le mouvement d’une oeuvre cinétique?” Coré: conservation et restauration du patrimoine culturel 19 (December): 13–18.]); members included Latin American artists Julio Le Parc and Horacio García Rossi. Martha Boto, Gregorio Vardanega, Jesús Rafael Soto, and Carlos Cruz-Diez also worked in Paris. In Brazil, Abraham Palatnik pushed painting into the fourth dimension, and in Argentina, Gyula Kosice used light, water, and translucent plastic to design cities for outer space.

The MFAH is one of the few museums to invest heavily in this type of art, and it can be difficult to find comparatives in public institutions that have staff conservators with whom to confer. The works are generally acquired from private collectors in Latin America or from the artists themselves or their descendants, and storage conditions have rarely been to museum standards. Many works had been in operation longer and more frequently than would be desirable in a museum setting, and worn-out components had been replaced without documentation.

The demands of frequent exhibition have necessitated a practical approach and a treatment-minded ethical framework. The conservation department has had an ever-increasing role in getting and keeping these works in running order, as the institutional mind-set shifts to seeing functionality problems in kinetic art as a preservation issue rather than an exhibition issue.

Gregorio Vardanega

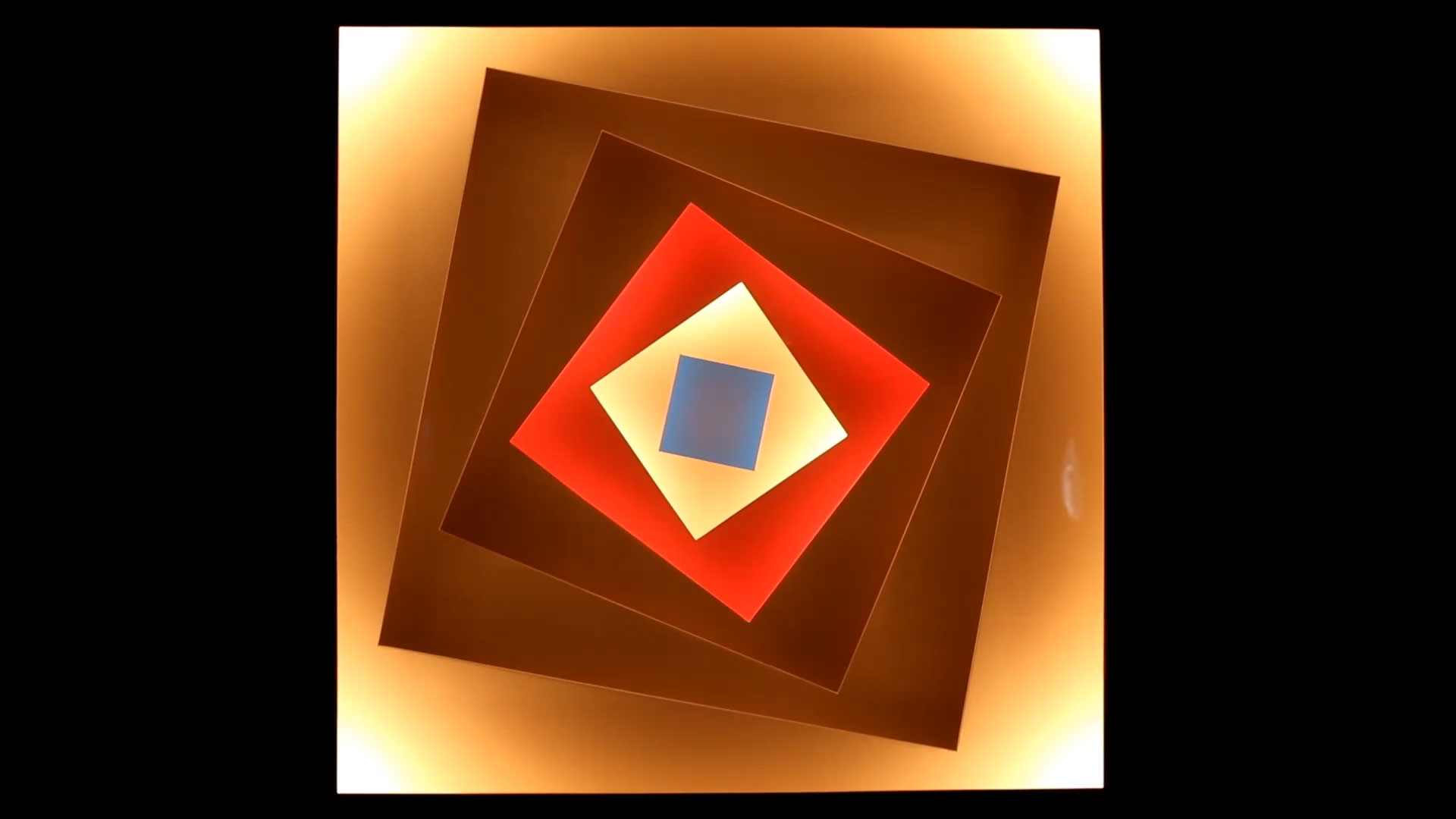

Gregorio Vardanega’s Espaces chromatiques carrées en spirale (Chromatic Spaces Turning in a Spiral) (1968) (fig. 9.1) had been shown at the museum twice before accessioning. When conservators first examined it in 2012, forty-nine of its sixty-three bulbs did not work.

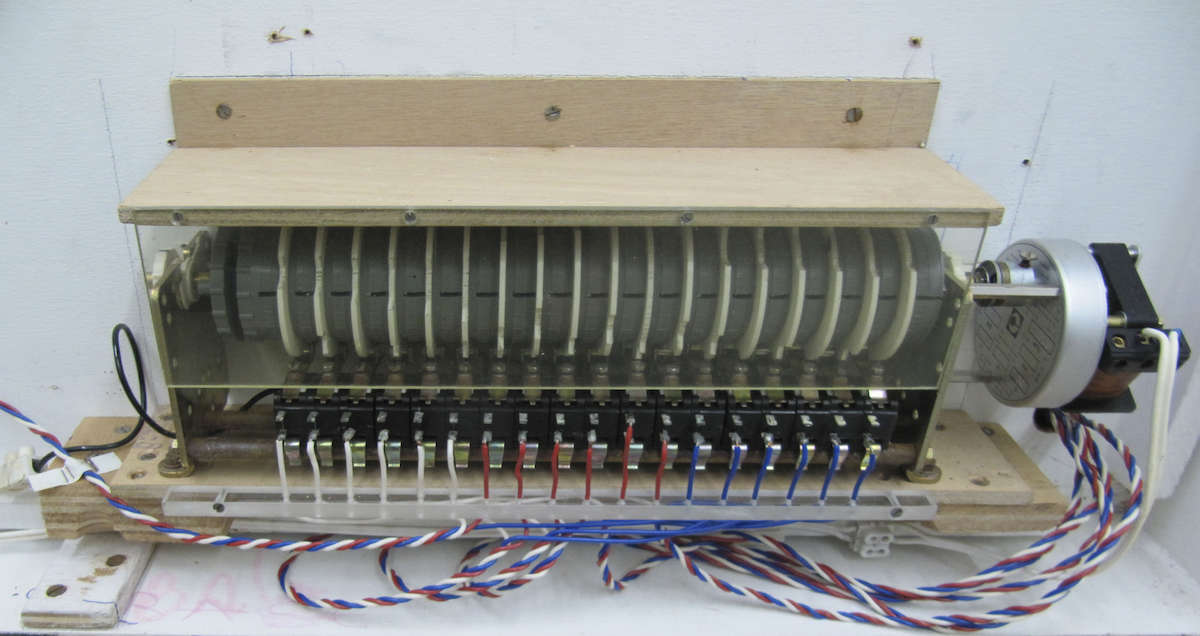

Offset white square panels, receding in size to the back of the artwork, have colored lights at each corner that produce the effect of a spiral. Behind each panel are groups of three small bulbs with blue and red plastic sleeves that create blue, red, and white light. The motor-driven analog sequencing system located inside the back panel works well, but the cylinder of hand-carved white plastic disks, which turn the switches on and off (fig. 9.2), will eventually deteriorate. Before that begins, this system should be documented, perhaps by 3-D scanning of the cylinder.

The E5850 Orbitec 15W 230V E10 bulbs are no longer available with exactly the same glass shape, but a very similar type was found through Don Schnapp,1 a specialty dealer with access to European dead-stock bulbs. All sixty-three bulbs were replaced to ensure a uniform appearance and a consistent electrical load, and to preserve the remaining fourteen functional original bulbs for future reference.

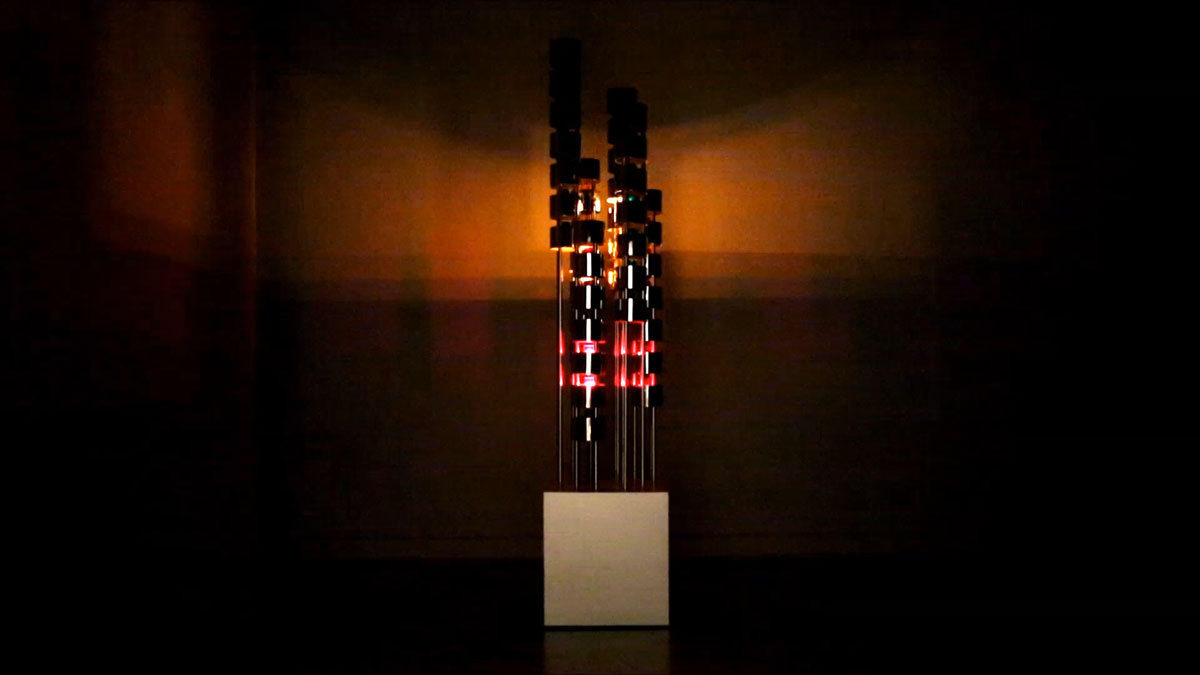

Couleurs sonores (Sound Colors) (1963–79) (fig. 9.3), Vardanega’s design for a futuristic city of skyscrapers, was accessioned in 2013, but, at 4.6m high, it was too tall for the intended gallery and unfortunately could not be included in Cosmic Dialogues. The work had been permanently installed in the artist’s studio and was donated to MFAH by his estate.

Plastic sleeves over clear bulbs create the colored lights, as in Chromatic Spaces, and the sequence is similarly controlled by a music box–like drum hitting a row of switches. These simple mechanical devices often resist obsolescence better than colored bulbs or modern, software-based programming, and the mechanisms were again found to be in very good working order. However, some of the plastic sockets for the bayonet-base bulbs had become brittle with age and light exposure, and three socket cups broke under the pressure of inserting the bulbs. Repairs done with epoxy reinforced with polyester mesh had a tendency to fail, and replacement of all these sockets with a brass version may have to be considered before display. All the bulbs currently work, but more have been purchased for the future.

Martha Boto

The initial examination of Martha Boto’s Déplacements optiques (Optical Displacements) (1967–69) (fig. 9.4) prior to exhibition found that two bulbs were dead. Luckily, Boto and her partner Vardanega seem to have shared materials: the bulbs were of the same type he had used in Chromatic Spaces and were therefore on hand in the conservation lab.

Toward the end of the exhibition, however, Déplacements optiques began to have intermittent problems. The motor would noticeably slow down and make a harsh grinding noise, and then stop making the noise and return to normal speed within a few minutes. After deinstallation, we examined it in the lab, and we discovered that a thick layer of grease had been applied, unnecessarily, to the workings in the gearbox. The motor itself ran smoothly when separated from the gearbox; after the gearbox was cleaned, the object worked perfectly.

Boto’s Optique electronique (Electronic Optic) (1965) runs on 110V and uses E26 screw-base 60W bulbs. Therefore, unlike many other works in the collection, replacement bulbs have always been easily obtainable in Houston, and the object had run reliably through two previous exhibitions. Twelve days after installation in Cosmic Dialogues, however, the motor died.

The original was a Crouzet synchronous motor with a SAPMI Type 835 SYN gearbox with an output of 2 rpm. As a suitable-size 2-rpm direct-drive motor was on hand in the lab—an extra purchased during treatment of the Abraham Palatnik work, discussed below—the original motor and gearbox were both removed and replaced, allowing immediate reinstallation. The original components were saved for future reference. Although some might argue that an element of the object’s integrity is lost by this change in running mechanism, this minor loss is far outweighed by the preservation of the viewer’s experience, which was the primary interest of this group of artists.

Julio Le Parc

The MFAH has two Julio Le Parc sculptures, one from 1960–66 and another from 1968, both titled Continuel-lumière mobile (or Continuous light mobile or Unceasing Light Mobile). They produce a complex, irregular pattern of moving lights on the surrounding walls. Although this pattern appears to be the result of programming, it is actually caused by simple garlands of metal disks strung on monofilament, illuminated from below by incandescent bulbs. The air currents in the room move the disks, and they cast reflections throughout the darkened gallery. We noted during installation that the boxes housing the bulbs got extremely hot, and replacement with LEDs was considered for safety reasons. It was decided, however, that the heat generated by the bulbs contributes to the movement of the disks, and the incandescent bulbs were left in place.

Horacio García Rossi

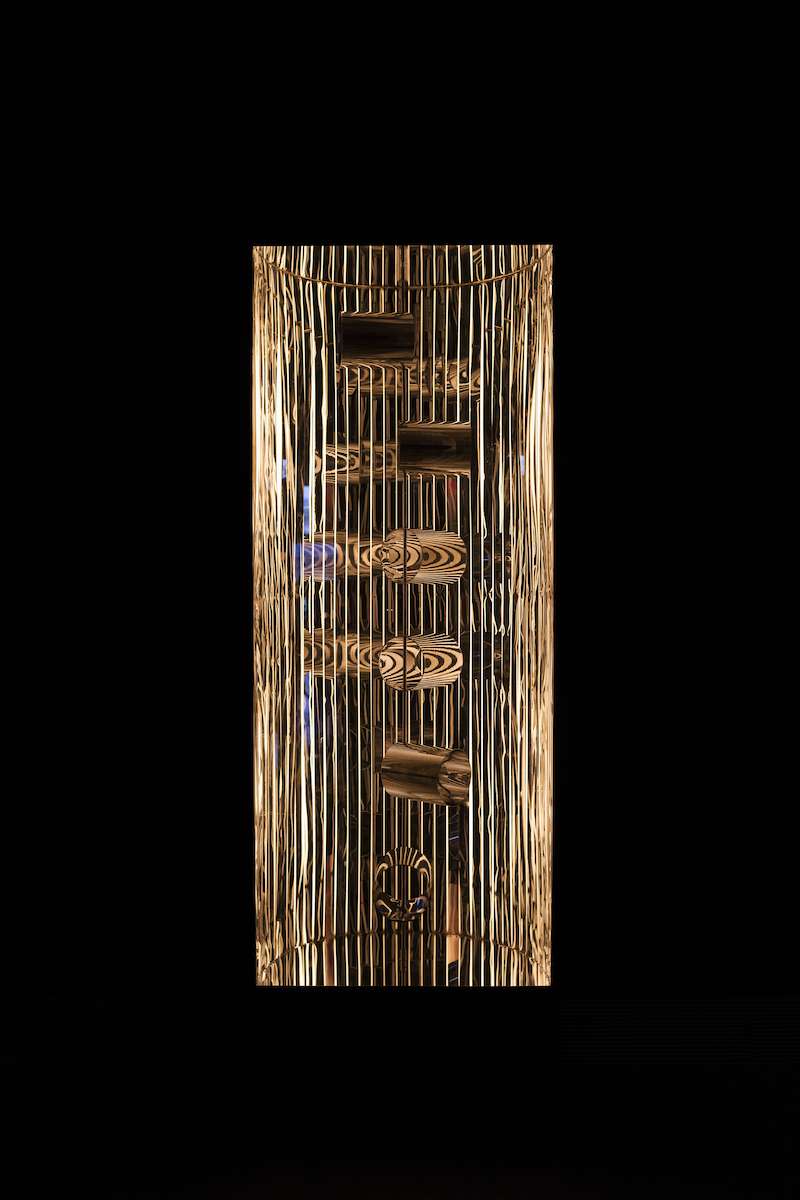

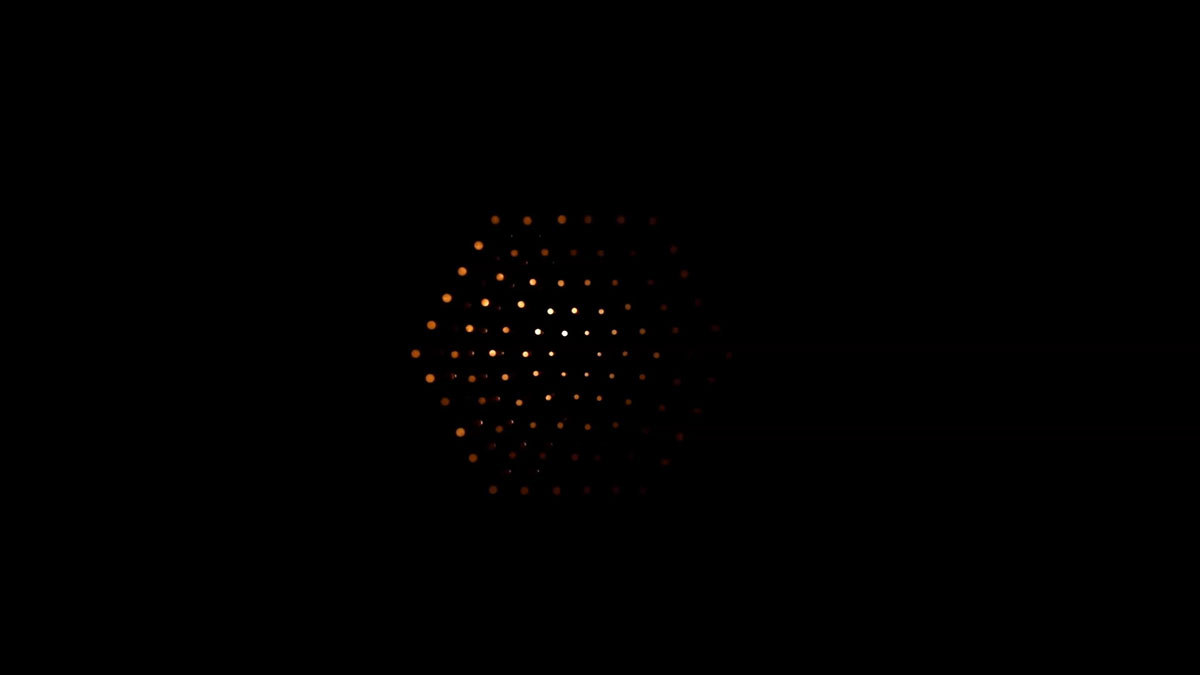

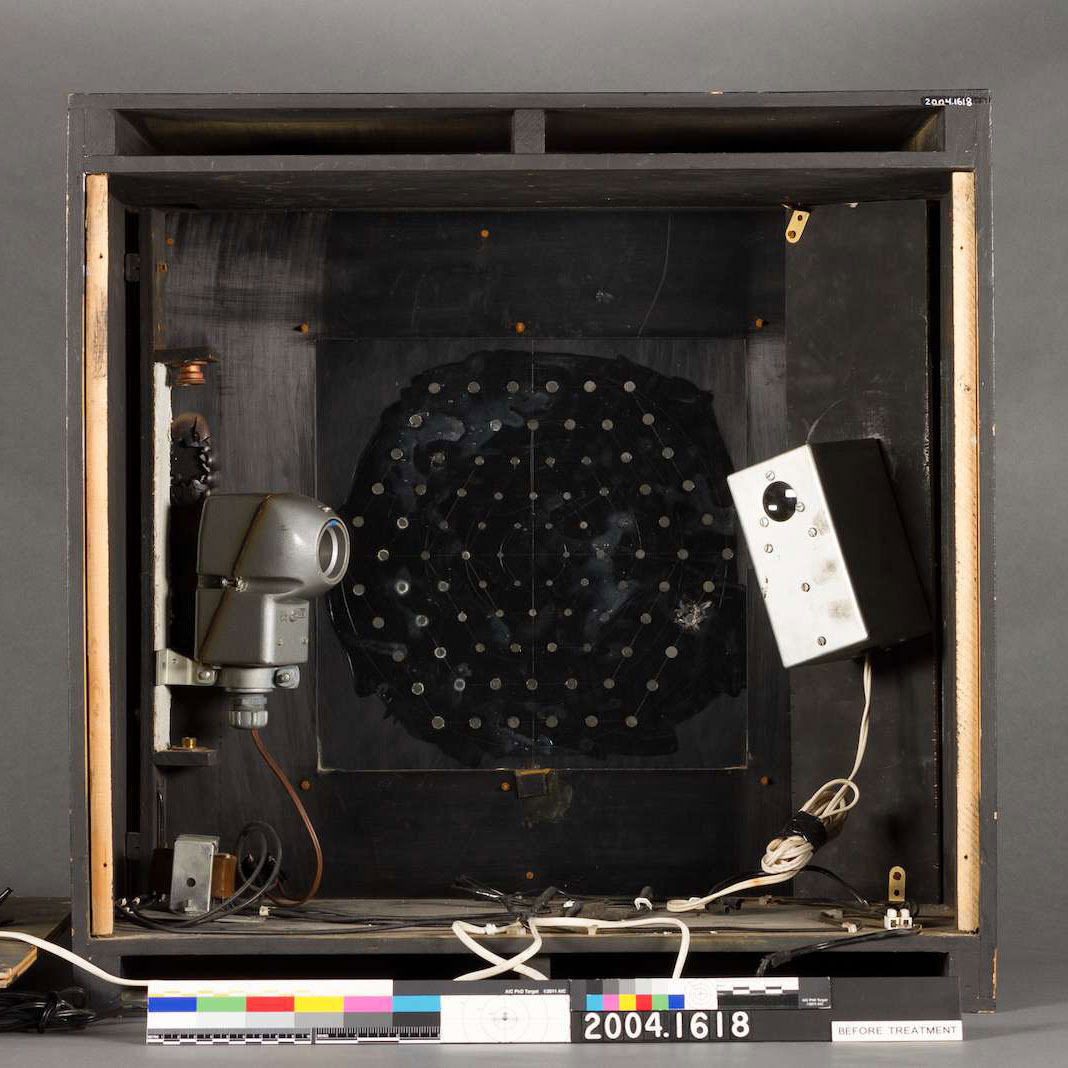

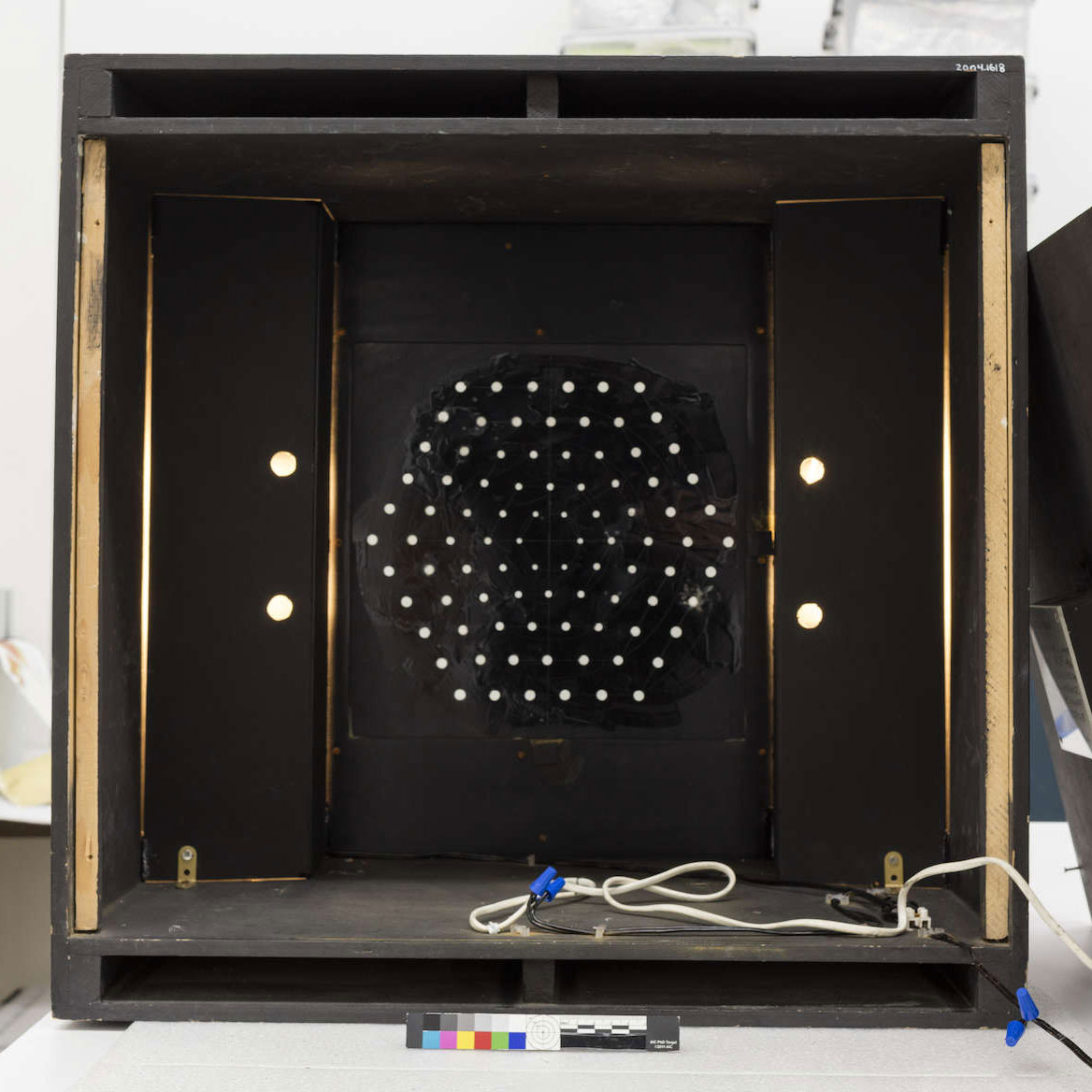

Horacio García Rossi’s Structure à lumière instable no. 29 (Unstable Light Structure No. 29) (1966) (fig. 9.5) had been shown in a previous exhibition just after acquisition, but the lights had since stopped working. There are ninety acrylic rods of different thickness and length on the exterior. Two lights on the inside of the front panel (fig. 9.6a) project light onto the back of the box, on which a wooden disk with a forest of shiny metal squares (fig. 9.6b) is mounted. The disk is turned by a motor, causing the metal squares to shift position on their wires, casting light randomly through the acrylic rods.

The light fixtures were reused parts from electric-eye systems, one of which still had its label: “Berkeley Dynamic, Burlingame, California, 1981.” Before purchase by the MFAH, this work had only one owner, California sculptor Benbow Bullock, so the Berkeley Dynamic fixture must have been installed by Bullock. Four severely charred holes on the inner acrylic layer behind the front panel do not correspond in location to these fixtures, indicating that the original configuration was considerably different.

We contacted García Rossi’s family for information but received no reply. Working on a theory that the original light source had been four bare incandescent bulbs, replaced by Bullock with a safer alternative after a fire, we tested a substitute system of four 60W-equivalent LED bulbs aligned with the burn marks. This created far too much even light inside the box, resulting in all the acrylic rods in front being solidly illuminated, with almost none of the flickering necessary for the required “unstable” effect. The two pieces of asbestos-lined wood used by Bullock to mount the projector fixtures seemed likely to be recycled elements of the original arrangement, providing a baffle to reduce the light; however, without concrete evidence, we could not make changes to the object. Instead, we found replacement bulbs to display the object running as originally received.

Shortly before installation, we finally succeeded in contacting García Rossi’s family and arranged a visit by Domitille d’Orgeval, a French art historian who is intimately familiar with García Rossi’s work. She judged that the object’s appearance with the electric-eye fixtures was acceptable for display, but also contacted a friend of the artist, Alejandro Marcos, who has worked on similar objects for French collectors. He provided sketches of the two styles of baffle used by García Rossi, which confirmed that the pieces of wood used by Bullock as a mount, one with two circular cutouts, were indeed very likely part of the original arrangement. He also said that the bulbs would have originally been 40W incandescent, which he has been replacing with LEDs in his own treatments.2 The validity of Marcos’s sketch was confirmed by later examination of a smaller work in the same series owned by Houston’s Sicardi Gallery, which was found to have similarly shaded bulbs.

After Structure à lumière instable no. 29 was deinstalled, we used Marcos’s sketch as a reference for treatment. The replacement LED bulbs3 greatly reduced the amount of heat generated, so we eliminated the asbestos lining and substituted four-ply mat board for the original wood (for convenience) (fig. 9.6c). The visual result when the object was turned on was somewhat brighter and livelier, with the flickering fully restored (see fig. 9.5).

Abraham Palatnik

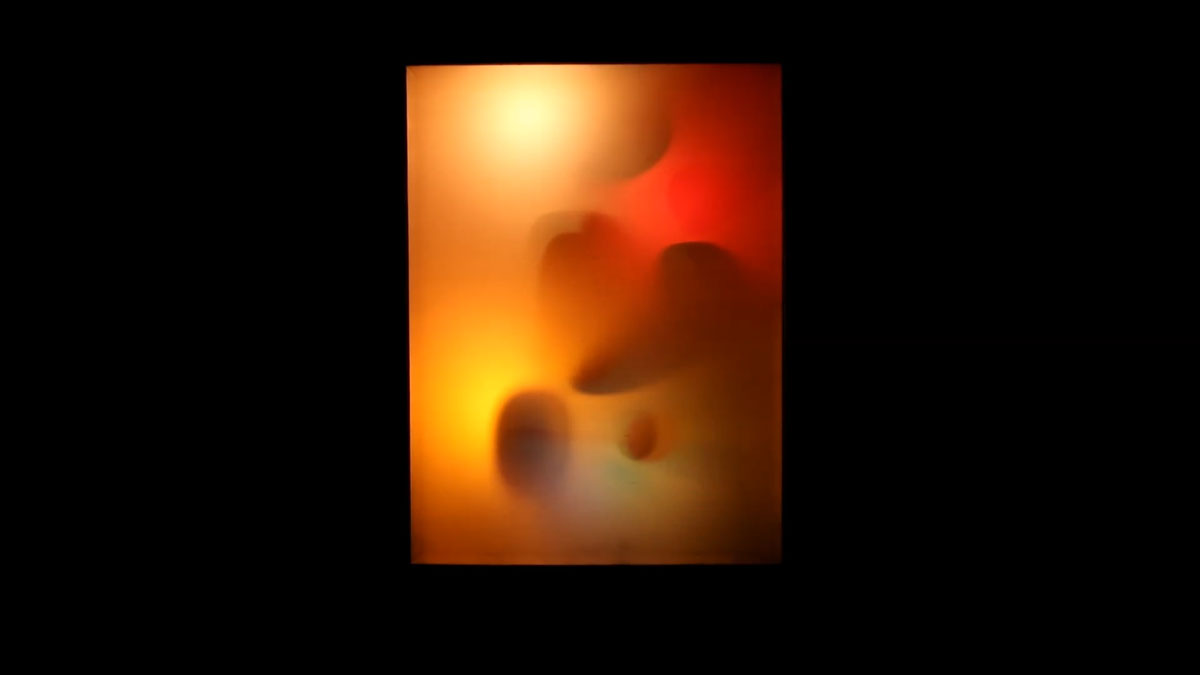

In Brazil, Abraham Palatnik, an artist and engineer of Russian descent, abandoned traditional painting after seeing artwork made by schizophrenics, which he felt surpassed his own efforts despite their lack of formal training (Citation: Osorio 2004:97 [Osorio, Luiz Camillo. 2004. Abraham Palatnik. São Paolo: Cosac Naify.]). Seeking to connect more directly to the subconscious, he made his first kinetic work in 1949, in which colored lights are diffused through a plastic screen and shaded by moving cardboard shapes. The museum owns a 1962 version, Aparelho cinecromático (Chromo-kinetic set) (fig. 9.7).

Twenty-five colored and clear frosted bulbs inside Aparelho cinecromático turn on and off in a programmed sequence, while black cardboard shades move in front of the bulbs, casting shadows and obscuring lights (fig. 9.8). Some of the bulbs no longer functioned. When Palatnik visited the museum before this work was shown in the 2007 exhibition Dimensions of Constructive Art in Brazil: The Adolpho Leirner Collection, we discussed the problem of bulb replacement, because the bulbs were no longer made in the same color tones. We decided to replace the nonfunctioning bulbs with locally sourced colored bulbs for the exhibition, but the new bulbs produced noticeably less saturated colors. Some of the old bulbs are almost certainly replacements, but there is no documentation of the original color configuration, so the condition of the object upon accessioning is being used as the benchmark. Palatnik himself was unconcerned about the exact color of the bulbs or the replacement of any parts. During the 2015 treatment, we colored replacement bulbs with glass paints4 using an airbrush to mimic the saturation of the older ones. The surviving old bulbs were removed for future reference.

Since then, we have explored Philips’s Hue system5 as a possible alternative to the painted bulbs. According to the manufacturer, these wireless-connected LED lights can create sixteen million different colors. Testing has shown that this is not yet the case: none of the color matches was as good as the painted replacements in value, hue, or saturation. Also, the Hue bulbs created a white center to the cast light that the old bulbs did not. Such “smart” bulbs will probably be useful to conservators in the future, however, as technology improves.

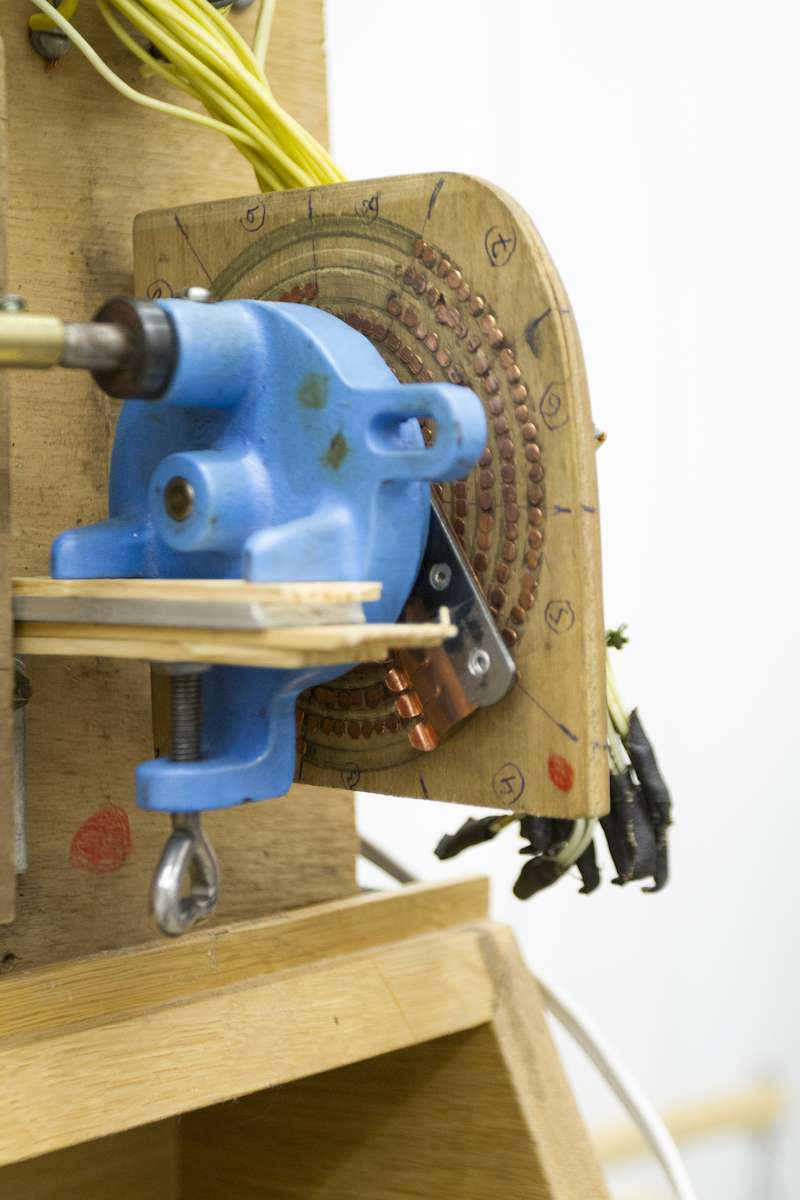

Other issues that have arisen include the wearing away of the copper comb, a critical element that makes the electrical connection from the power source to the various wires for the bulbs (fig. 9.9). When the comb does not meet the circuit board, some bulbs do not light as they should, and sparks occur as the current jumps that short distance. In 2014 the comb had worn away to such an extent that it was necessary to replace it with a replica cut from copper sheet. The replacement comb became noticeably worn during the 2015 exhibition, which suggests it will have to be remade quite frequently. The copper elements on the circuit board are also wearing away, and this will need to be addressed in the future.

The motor, which moves both the cardboard paddles and the copper comb, is the other main problem. By 2009 the original 2-rpm SAPMI Type 392 motor had stopped working and needed to be replaced urgently for a loan. We could not find a 110V 2-rpm motor of suitable size in time, so we substituted a 24V 1-rpm motor plus transformer, intending to find a more appropriate motor in the future. The half-speed replacement motor also ran in the opposite direction to the original motor, requiring the removal of two gears that Palatnik had used to reverse the direction of movement. The resulting output is therefore at the correct speed and in the correct direction, but the means of achieving it is different. The alteration in the location of the circuit board caused by the subtraction of the two gears might be considered ethically problematic, as a change to the artist’s original design for the mechanism. However, it eliminated a true weak link in the design, reducing the likelihood of future breakdowns that might damage other parts of the object, and it produced a functional object from a nonfunctional relic. During the 2014 treatment, the 1-rpm motor was replaced with a 2-rpm alternative,6 restoring the object’s original speed while maintaining the newly simplified version of the drive shaft.

Gyula Kosice

The work of Slovakia-born Argentinean artist Gyula Kosice is similarly science-focused, with a particular emphasis on space travel—in 1944 he declared that “Man is not to end his days on Earth” (Citation: Kosice 1944 [Kosice, Gyula. 1944. “La aclimatación artística gratuita a las llamadas escuelas.” Arturo: Revista de artes abstractas 1 (Summer): n.p.]) and commenced a decades-long project imagining hydraulics-powered living environments for humans in space. Kosice’s iconic installation La ciudad hidroespacial (The Hydrospatial City) (1946–72) (fig. 9.10) is kinetic only in the sense that the hanging “habitats” move slightly with the air currents in the room. However, we have had to replace many elements on the wall-mounted Constelaciones no. 1–6 (Constellations no. 1–6), molded acrylic light boxes backlit with fluorescent tubes. The sockets and ballasts are reaching the end of their lives, and currently available components are slightly different in shape, making replacement far from straightforward. Late in life, the artist replaced the lights on his older works with LED strips when they developed problems. At what point should the MFAH abandon the troublesome fluorescents and follow suit? The quality of the light would undoubtedly change, eliminating the characteristic flickering of fluorescents.

As the components of light-based kinetic artworks become technologically obsolete and irreplaceable, their conservation has a challenging future. In some cases it may become impossible to maintain functionality along with every aesthetic aspect of the original experience. If the artist’s practice involved updating the technology of his earlier works, should the conservator imitate this? Or are visible changes only acceptable when it becomes impossible to keep the original lights operational? Thus far the MFAH has not taken such drastic steps for purely preventive reasons, but an upcoming loan of eight of these works, including The Hydrospatial City, may precipitate a reevaluation. Releasing these artworks to be operated under the stewardship of another institution has caused some concerns about preservation.

A work by Jean Tinguely displayed in a nonoperational state, while lacking a vital element of its original meaning and beauty, can still be appreciated for its form (Citation: Gagneux 2007:16 [Gagneux, Dominique. 2007. “Doit-on entretenir le mouvement d’une oeuvre cinétique?” Coré: conservation et restauration du patrimoine culturel 19 (December): 13–18.]). In contrast, the nature of the works discussed above generally precludes static display: some are not much more than a plain box when they are not functioning. Additionally, fetishizing the physical material and its connection to the artist over functionality is not in keeping with the philosophy of most of these artists, who explicitly described their works as industrial, scientific projects. In one of its manifestos, the GRAV group actually condemned the “cult of personality” of the individual artist in favor of the concept and the experience (Citation: GRAV 2004:513 [GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel). 2004. Reprint of the manifesto “Transformer l’actuelle situation de l’art plastique,” 1961. In Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America, edited by Héctor Olea and Mari Carmen Ramírez, 513. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.]). Showing a video of the object in operation, next to the static original, is sometimes a good option for unreliable kinetic artworks. However, video is a less satisfying substitute for an immersive, light-based work, as the alteration to the appearance of the surrounding walls and space is entirely lost in the flat plane of a video monitor. Instead, at the MFAH, parts are replaced and repaired as needed, with limits on running time to reduce that necessity as much as possible.

During Constructed Dialogues: Concrete, Geometric, and Kinetic Art from the Latin American Art Collection in 2012, five of the electric works ran constantly during the day, and one could be activated by the visitor. In Cosmic Dialogues in 2015, the six works with more robust mechanisms were run constantly, and three were activated by a single motion sensor. In retrospect, all of the works should have been turned on by individual motion sensors. The breakdown of the motor in Boto’s Déplacements optiques served as a sharp reminder that works long considered robust are not immortal. In addition, the different states of the works confused both guards and visitors. The single motion sensor was not ideal, as it undermined the individuality of the works and, on a practical level, caused the security staff to stand in the doorway of the room rather than at its center, to avoid constantly activating the works. Separate proximity sensors for each object would allow a more contemplative viewer to experience a work for an extended period, while reducing runtime overall. This may be implemented in future installations.

The expanding role of MFAH conservators in the display of these objects has been an interesting exercise in compromise and collaboration. In the past, these objects have been worked on by the artist’s friends and relatives, museum electricians, handy registrars, and preparators. All of these individuals have valuable expertise to contribute, and we continue to seek their assistance. But the conservator is better placed to collate this expertise, weigh the suggestions of all parties, and document all action undertaken. Preparing these artworks for permanent galleries offers further opportunities to develop best protocols for display while maintaining functionality.

Notes

- Orbitec E10 230V 15W. Don Schnapp Specialty Bulbs, 2600 Pope Canyon Road, Saint Helena, CA, 94574. Don Schnapp has since retired. ↩

- Alejandro Marcos, in discussion with the authors, April 2015. ↩

- LED bulbs, soft white A19 450 lumens, 2,700K, 40W equivalent, manufactured by Philips USA. Supplied by Home Depot, Atlanta, GA, 30339-1834; http://www.homedepot.com/p/Philips-40W-Equivalent-Soft-White-A19- LED-461145/206783826. ↩

- Vitrea 160 Glass Paints, manufactured by Pébéo. Supplied by Dick Blick Art Materials, P.O. Box 1267, Galesburg, IL, 61402-1267; http://www.dickblick.com/items/02950-1109/. ↩

- Philips Lighting B.V. “Meet Hue.” Philips, accessed July 28, 2016, http://www2.meethue.com/en-us/productdetail/philips-hue-white-and-color-ambiance-starter-kit-a19. ↩

- 2-rpm motor, counterclockwise synchronous geared Autotrol PX-300. Manufacturer: Autotrol. ↩

Bibliography

- Gagneux 2007

- Gagneux, Dominique. 2007. “Doit-on entretenir le mouvement d’une oeuvre cinétique?” Coré: conservation et restauration du patrimoine culturel 19 (December): 13–18.

- GRAV 2004

- GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel). 2004. Reprint of the manifesto “Transformer l’actuelle situation de l’art plastique,” 1961. In Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America, edited by Héctor Olea and Mari Carmen Ramírez, 513. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- Kosice 1944

- Kosice, Gyula. 1944. “La aclimatación artística gratuita a las llamadas escuelas.” Arturo: Revista de artes abstractas 1 (Summer): n.p.

- Osorio 2004

- Osorio, Luiz Camillo. 2004. Abraham Palatnik. São Paolo: Cosac Naify.

- Popper 1968

- Popper, Frank. 1968. Origins and Development of Kinetic Art. London: Studio Vista.

- Ramírez 2004

- Ramírez, Mari Carmen. 2004. “A Highly Topical Utopia: Some Outstanding Features of the Avant-Garde in Latin America.” In Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America, edited by Héctor Olea and Mari Carmen Ramírez, 1–15. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- Rossi 2012

- Rossi, Cristina. 2012. “Imágenes inestables: Tránsitos Buenos Aires-Paris-Buenos Aires.” In Real/Virtual: Arte cinético argentine en los años sesenta, edited by María José Herrera, 47–67. Buenos Aires: Asociación Amigos del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

- Suárez 2007

- Suárez, Osbel. 2007. “The Logic of Ecstasy.” In Lo[s] cinético[s], edited by Osbel Suárez and Eugenio Fontaneda, 243–47. Madrid: Artes Gráficas Palermo.