Opening Remarks: The Kinetic Collection at the Museo del Novecento, Milan

- Iolanda Ratti

The cultural milieu in Milan during the late 1950s and early 1960s was extremely lively. Lucio Fontana’s spatial research influenced artists such as Piero Manzoni, Enrico Castellani, and Agostino Bonalumi, as well as groups that sought to upset traditional art practices not only in terms of media but also by stressing the role of the spectator in giving significance to the artwork.

In 1959 Giovanni Anceschi, Davide Boriani, Gianni Colombo, and Gabriele Devecchi met at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera and formed Gruppo T (where T stands for “time”). They started producing works together, and these where exhibited for the first time in Miriorama 1, organized in January 1960 at Galleria Pater in Milan.

The term miriorama, from the Greek myrio (meaning “an endless quantity”) and orao (to see), is the title of the group’s manifesto, written in October 1959 and presented for the Galleria Pater exhibition. The manifesto asserts that reality is an expression of the variable perception of space and time. The traditional idea of art is overtaken: artworks have to be realized in the same material as reality. Movement shall therefore represent a continuous variation in terms of space and time and also reflect the rapid improvement of technology.1

The group’s first environmental artwork, Grande oggetto pneumatico, was produced in 1959 and exhibited in Miriorama 1. Composed of seven long polyethylene balloons, it occupied the entire space of the gallery. The shape of the artwork changed constantly because the balloons were alternately inflated through an air nozzle and because the visitors had to move them to walk through the space.

From January to February 1960, the Galleria Pater hosted four solo exhibitions (Miriorama 2 through Miriorama 5), seen as a progression of and follow-up to the first show, each dedicated to a member of the group: Boriani, Devecchi, Colombo, and Anceschi. The second group show, Miriorama 6, was organized in March 1960, and it was the first time Grazia Varisco was a member of Gruppo T.

In 1962, when Gruppo T participated in the exhibition Arte programmata: Arte cinetica, opere moltiplicate, opera aperta at the Olivetti showroom in Milan, Umberto Eco defined the group as “kinetic” and “programmed.”2 Artists introduced the use of new industrial materials and objects in their works, such as plastic, polystyrene, electric motors, UV lights, and strobe lamps. The aim of their research was to invite the public to interact with the art, creating a new relationship between visitors, artwork, and exhibition space.

Gruppo T continued its collaborative activities until the end of the 1960s, establishing relations with European groups researching the idea of movement, such as ZERO in Düsseldorf and Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) in Paris, and trying to deconstruct the traditional art system. An ending point of the group’s activity could be considered 1968, when Colombo won first prize at the Venice Biennale. From the beginning of the 1970s each artist followed his or her own path, often with interesting experimentations in the field of design.

The history of Milan’s municipal collections of twentieth-century art dates to the beginning of the century and includes acquisitions, donations from private collectors, and long-term loans. Yet it was only in 2010 that the Museo del Novecento opened as a permanent venue that provides a narrative for Italian art from the avant-garde to the present, with a focus on Milan. When the committee started planning the new museum in 2008, it dedicated a section to programmed and kinetic art that included space for Gruppo T, which was not yet represented in Milanese institutions. Important artworks referencing the visual-kinetic research from the late 1950s had entered the museum’s collections from the 1970s through the 1990s; Colombo’s Strutturazione pulsante (1959), Enzo Mari’s Struttura no. 386 (1957), Bruno Munari’s Aconà biconbì (1964–67), and Dadamaino’s Oggetto ottico dinamico no. 1 (1963) were especially significant acquisitions.

The collaboration of artists, collectors, and archives (specifically the Archivio Gianni Colombo) was essential to attract long-term loans and achieve a panorama of Gruppo T’s work. It was also fundamental for the re-creation of some of the group’s environmental works from original documents such as drawings and plans and with the direct supervision of the artists. Anceschi’s Ambiente a shock luminosi (1964), Boriani’s Ambiente stroboscopico no. 4 (1967), Devecchi’s Ambiente-Strutturazione a parametri virtuali (1969), and Colombo’s Topoestesia (Tre zone contigue—Itinerario programmato) were re-created in Milan in 2010.3 These facsimiles provided a better understanding of the boundaries between a kinetic object and a kinetic space, and they enabled research and analysis of the reaction and interaction of the public with the work of art.

Conservation Issues

Kinetic artworks present considerable conservation and maintenance challenges and, beyond the specificities of individual cases, permanent display is the first matter to be considered. The Museo del Novecento is open seventy hours a week, and thirteen hours each on Thursdays and Saturdays. Artworks on view are activated for long periods, and this causes stress to lights and motors, especially to original motors that had not been designed for long-term use. To address the issue, sensors and timers were installed so that the works are activated only when visitors are present and only for about one minute. While this has considerably reduced the need for extraordinary interventions by technicians, wear and tear remain the primary conservation issues, especially after many years of display.

The Museo del Novecento’s approach thus far has been that of preserving the original components by preemptively replacing them with new ones, even when the originals still work. In this case, the overall “authenticity” of the artwork is potentially preserved, since its original components, such as motors or rubber drive belts, are intact, functional, and available for a possible future reconstruction.

This approach was used during the restoration of Colombo’s Strutturazione pulsante, a work composed of rectangular modular polystyrene panels combined orthogonally; behind the panels, a motor-driven system of slats produces the alternating movement of the panels (fig. 0.1). In conjunction with a cleaning of the polystyrene parts, the museum decided, with the approval of the Archivio Gianni Colombo, to replace the two still functional but very fragile plastic silicon belts (from the late 1950s) with new belts. The original belts were preserved in the archive, so the artwork could possibly be rebuilt with its original components in the future.

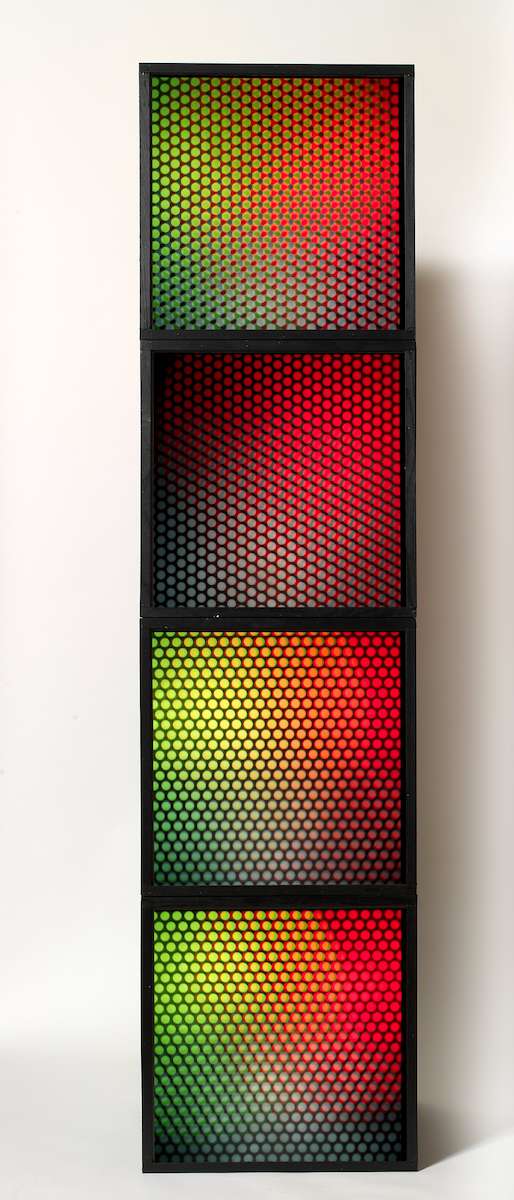

Preventive substitution was also adopted for Anceschi’s Struttura tricroma (1964), a work composed of four motorized cubes and three halogen lamps. The back projection, made by the lamps, creates a regular pattern of colored circles on the “screen” of the cubes’ faces (fig. 0.2). The four electromechanical 220V motors—one for each cube—were constantly under stress because the rotating blades, which produce the movement of the colored circles, were too heavy. The blades have been preventively replaced with new blades that are lighter in weight.

So far, the museum has limited its substitution of components to those that can be considered “tools” necessary for the artwork’s function but not “constitutive” of the artwork’s aesthetic value. For display, the focus is on the historical value of the object and respect for its components. Other specific conservation strategies, such as emulation, have been adopted for environmental installations. Although the 2010 reconstruction of Anceschi’s Ambiente a shock luminosi (fig. 0.3) followed the original drawings of 1964 in terms of space and general setup, the artist and the curator decided during the planning process to use strobe lights, which did not exist when the work was conceived. This choice was made because the artist preferred the public’s response to the environment rather than a reconstruction completely faithful to the original.

Preserving kinetic artworks also requires interdisciplinary teamwork: the knowledge required to understand these works often goes beyond the traditional training of curators and conservators. Since its inception, the Museo del Novecento has collaborated with Attitudine Forma, a company providing technical services for contemporary art that, since 1996, has worked with the most important museums and institutions in Italy, as well as with several international artists. The company, and in particular Roberto Dipasquale, was involved in the production of the museum’s environments and is in charge, together with the collection curator, of the monitoring and preventive conservation program.

Exhibiting these “spaces/environments” also has a consequence in everyday museum life. Some issues that don’t directly relate to the artworks’ state of conservation nevertheless enter the realm of preservation, as they can change the perception of the work or alter the artist’s intention. If, in traditional artworks, issues of safety and accessibility may not be an immediate concern, they play a role in kinetic environments, where visitors must sign a release form before entering a space that could be dangerous for those with heart conditions or epilepsy. Accessibility is an issue when the disabled are unable to enter the space.

Being partner and host of the Keep It Moving? Conserving Kinetic Art symposium was a particularly important occasion for the Museo del Novecento. It was an opportunity to share knowledge and open a dialogue with many institutions worldwide that, every day and with immense professionalism, face similar problems. And, as it turns out, have very similar discussions on if, and how, to keep it moving.

Notes

- “Quindi, considerando l’opera come una realtà fatta con gli stessi elementi che costituiscono quella realtà che ci circonda, è necessario che l’opera stessa sia in continua variazione” (Considering the artwork as a reality made with the same elements that constitute the same reality surrounding us, it is necessary that the artwork itself be in continuous change). “Consideriamo la realtà come continuo divenire di fenomeni che noi percepiamo nella variazione” (we consider reality as an ongoing series of phenomena that we perceive within the variation itself). Gruppo T, Miriorama 1, Manifesto, Galleria Pater, Milan, 1960. ↩

- Olivetti, founded in 1908 in Ivrea, Italy, was one of the first companies to produce typewriters and, at the end of the 1950s, the first computers in Italy. For a bibliography on the relationship between Olivetti and Gruppo T, see Sergio Morando, ed., Almanacco letterario Bompiani (Milan: Bompiani, 1961); Umberto Eco, “Arte programmata: Arte cinetica, opere moltiplicate, opera aperta,” in Arte programmata: Arte cinetica, opere moltiplicate, opera aperta (Milan: Officina Arte Grafica Lucini, 1962), the catalogue for the exhibition curated by Bruno Munari. Arte programmata was shown in different venues from 1962 to 1965: Olivetti showroom, Milan, May–June 1962; Olivetti showroom, Venice, July–August 1962; Gallery La Cavana, Trieste, December 1962–January 1963; Goppinger Galerie, Düsseldorf, June–July 1963; Royal College of Art, London, May–June 1964; Loeb Student Center, New York, July–August 1964; Florida State University, Tallahassee, October–November 1964; Columbia Museum of Art (South Carolina), January–February 1965; and the University Art Museum, Andrew Dickson White House (Ithaca, New York), March–April 1965. See also Marco Meneguzzo, Enrico Morteo, and Alberto Saibene, eds., Programmare l’arte: Olivetti e le neoavanguardie cinetiche (Monza, Italy: Johan & Levi, 2012), the catalogue of the exhibition held at Olivetti showroom, Venice, August–October 2012, and at Museo del Novecento, Milan, October 2012– February 2013. ↩

- Giovanni Anceschi’s Ambiente a shock luminosi was realized for the first time in 1964 for the exhibition Nouvelle tendance at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Pavillon de Marsan, Louvre. It was rebuilt in Milan in 1983 for the show Arte programmata e cinetica 1953/1963: L’ultima avanguardia, and in 2005 for the exhibition Gli ambienti del Gruppo T: Le origini dell’arte interattiva at Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (GNAM), Rome. The environments were always destroyed after the shows. Davide Boriani’s Ambiente stroboscopico no. 4 (1967/2005) was first conceived in 1967 for Paris V Biennale (Ambiente stroboscopico no. 3) and rebuilt (in the original version) in 2005 for the exhibition OP ART at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. It is on long-term loan from VAF Foundation. Gabriele Devecchi’s Ambiente-Strutturazione a parametri virtuali was first realized in 1969 at Galleria Il Diagramma, Milan, and later reinstalled many times with significant variations. The original 1969 version was re-created in 2005 for Gli ambienti del Gruppo T at GNAM, Rome, and at Museo del Novecento in 2010. Gianni Colombo’s Topoestesia (Tre zone contigue—Itinerario programmato) (1964–70) was realized for the 1964 exhibition Nouvelle tendance at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Pavillon de Marsan, Louvre, dismantled after the show, and not reconstructed until 2010 at Museo del Novecento. See Iolanda Ratti, Denis Viva, and Marina Pugliese, Arte programmata e cinetica in Museo del Novecento: La collezione (Milan: Electa, 2010), 285–97. ↩