8. Preserving Performativity: Conserving the Elusive in Aleksandar Srnec’s

Artwork

- Mirta Pavić

- Vesna Meštrić

Abstract

Srnec and His Luminoplastics

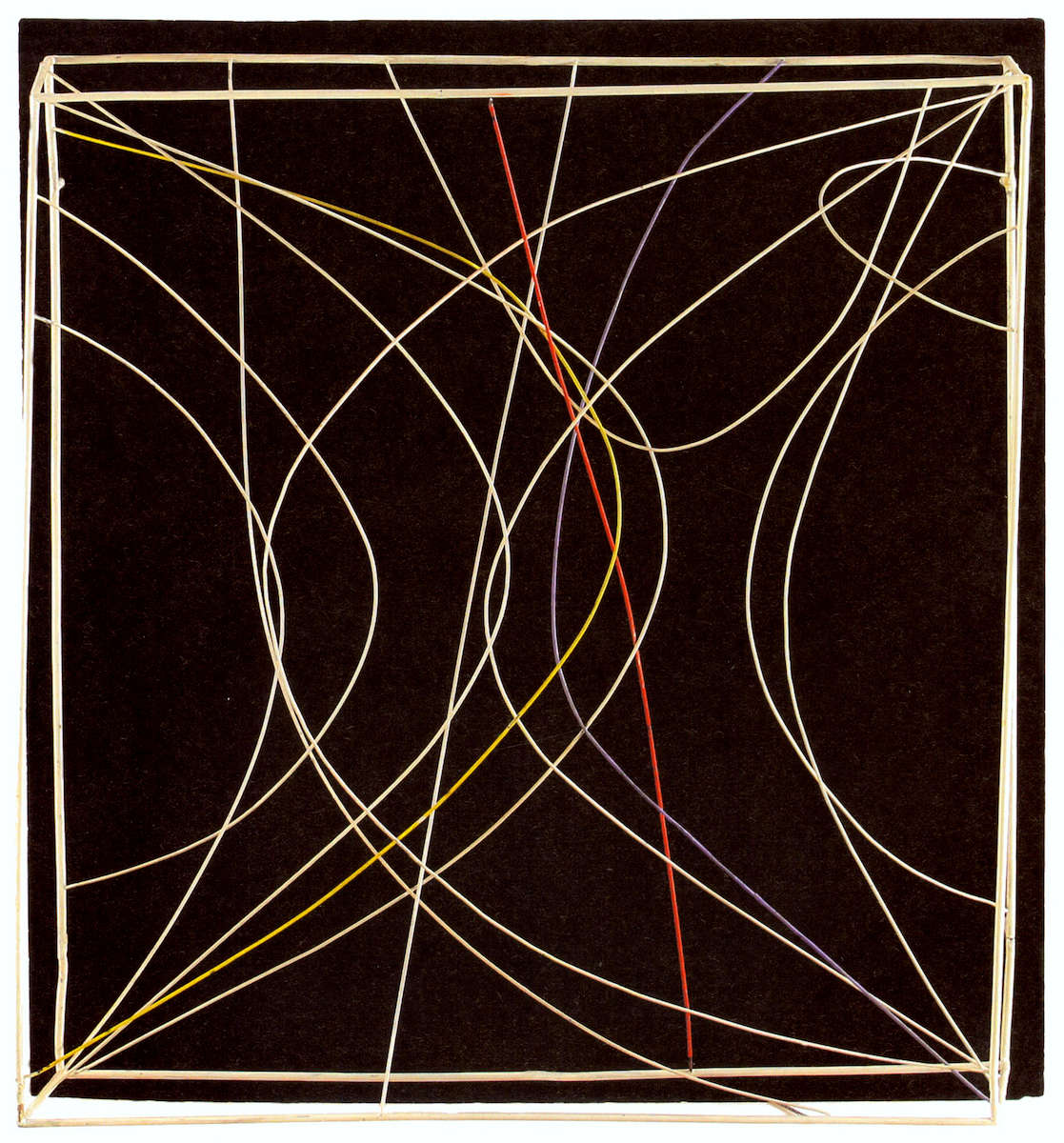

Aleksandar Srnec (Zagreb, 1924–2010) was a prominent Croatian artist whose work developed between 1950 and 1970, a vital period for the arts as well as for international culture, politics, and economics. Srnec was a member of the EXAT 51 group, active in the early 1950s, which sought to introduce experimentation into art and based its activities on the theories and traditions of Russian Constructivism, Bauhaus, and Neoplasticism. EXAT 51 was followed in the 1960s by the New Tendencies movement, which highlighted the need for the socialization and democratization of art and played a crucial role in the development of both the Croatian art scene (then Yugoslavia) and the international art scene. New Tendencies attracted artists who were experimenting with optical, kinetic, and luminokinetic art, in addition to influential scholars of Neo-Constructivist and kinetic art and information theory such as Giulio Carlo Argan, Abraham Moles, Matko Meštrović, and Alberto Biasi.1 Srnec’s creative drive found its basis in research and experimentation and, in 1953, led him to a key achievement of the EXAT 51 period, Space Modulator (fig. 8.1), the artist’s first object to give three dimensions to lines, that is, turning a drawing into a space. Space Modulator holds a special place in Srnec’s oeuvre because it was the first of a series of kinetic and luminokinetic settings, which he constructed and exhibited at New Tendencies shows during the 1960s. There is an obvious link with one of László Moholy-Nagy’s most important luminokinetic objects, Light Space Modulator (1930), but only at the formal level. Moholy-Nagy experimented with light and movement to create ambience, while Srnec, using light and movement, transformed the two-dimensional line motif into a three-dimensional medium.

The connection between two- and three-dimensional media was to become a distinctive feature of the artist’s work. Srnec called his luminokinetic works Luminoplastics (fig. 8.2), and through them he joined a large group of artists who experimented with space, from pioneers of kinetic art (such as Alexander Rodchenko, Naum Gabo, Vladimir Tatlin, Moholy-Nagy, and Alexander Calder) to his contemporaries (including Nicolas Schöffer, Otto Piene, Bruno Munari, Jesús Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely, Julio Le Parc, and Alberto Biasi, among others) (Citation: Denegri 2004:270 [Denegri, Jerko. 2004. Constructive Approach Art: Exat 51 and New Tendencies. Zagreb: Horetzky.]).

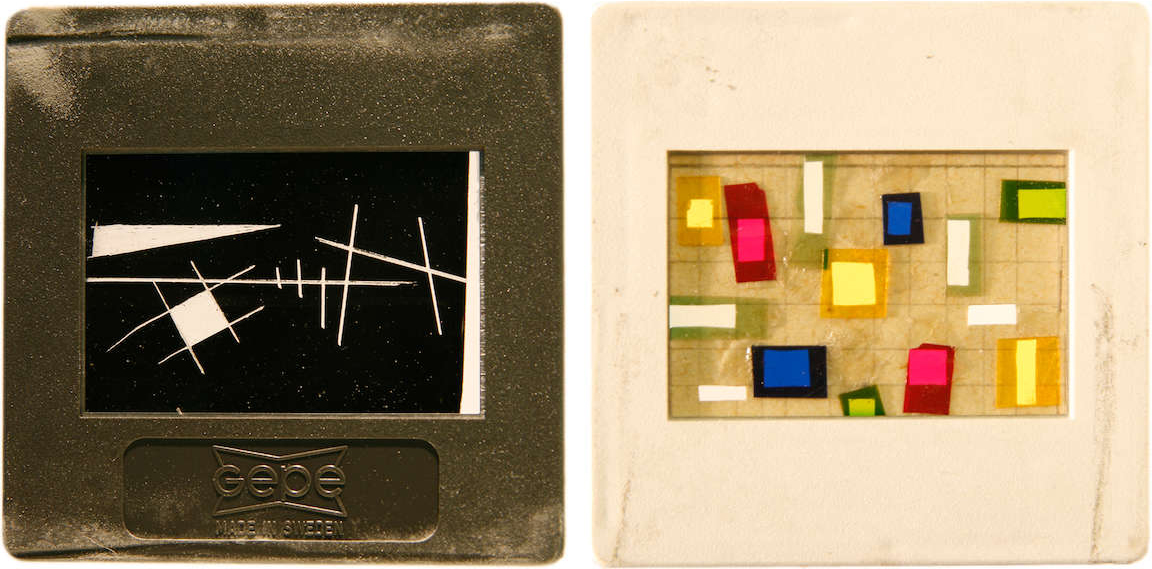

Srnec’s luminokinetic objects in the Museum of Contemporary Art (MSU) in Zagreb consist of combinations of various traditional artistic media and everyday materials. In his optical-kinetic research, Srnec used anything that might contribute to the marvelous play of light and movement, and very often this meant ordinary objects, such as electric motors from sewing machines, metal rods, wires, and projectors. However, Luminoplastic 1 (fig. 8.3), Srnec’s first luminokinetic object, has one element that is quite different from the artist’s other luminokinetic works: a projection of eighty slides (fig. 8.4). The slides were made using various techniques and materials, and a detailed analysis of each slide has shown that these are actually eighty miniature works of art.

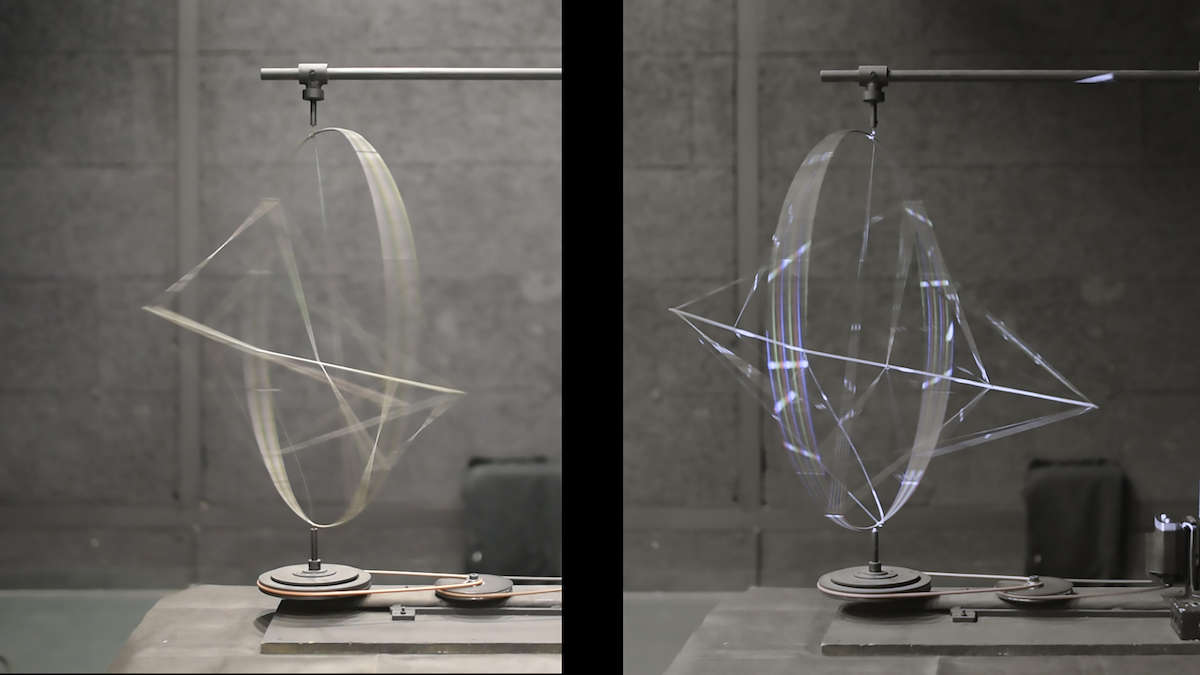

Srnec constructed Luminoplastic 1 between 1965 and 1967, and it is an extremely important work in the development of postwar Croatian art. The idea of Luminoplastic 1 is based on the dimensionality of line, movement, and light, and it represents a visual experience of light that is created in a darkened room. When not in operation, in daylight, it looks completely different (fig. 8.5). Srnec has described assembling the various elements and materials to construct the Luminoplastics as a process of “explaining something to himself.”2 He built the metal construction from wires joined along a rim on a wooden panel; an electric sewing machine motor rotates two plates joined by leather belts (also from a sewing machine), causing the construction to move. Slides are projected onto the rotating metal construction at set intervals. The image projected onto the moving object produces an optical illusion, and it is difficult for the viewer to discern how the work of art actually functions. Therefore, performativity is a key element of Luminoplastic 1, without which the different components have no purpose (Citation: Muñoz Viñas 2010:11 [Muñoz Viñas, Salvador. 2010. “The Artwork Became a Symbol of Itself: Reflections on the Conservation of Modern Art.” In Theory and Practice in the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art, edited by Ursula Schadler-Saubed et al., 9–19. London: Archetype.]). The projection of slides onto a revolving construction dematerializes both the object and its form, so that only the moving images remain: in Luminoplastic 1, only the space and light are important, as they create a dynamic, changing ambience (fig. 8.6).

This work was on display during the opening of the new MSU building in 2009, in the museum’s first permanent collection exhibition since its establishment in 1954.3 The constant use to which Luminoplastic 1 was subjected, eight hours per day, caused several failures in the electric motor and slide projector. The exacting requirements for exhibiting Luminoplastic 1 prompted the museum professionals to analyze the materials in detail and consider strategies for maintenance and display. This required a systematic and interdisciplinary approach as these elements, when becoming part of an art object, change their habitus, their original intent, and are used for a purpose for which they had not originally been intended. Thus, the curators and conservators faced a number of challenges relating to the maintenance and protection of the work, as well as the optimal way of exhibiting it. To approach the conservation decision-making process systematically, it was necessary to understand the object’s history and artistic-historical position as well as its mechanics and materials (metals, rubber, plastic, and photographic media). It was obvious that we would need the assistance of experts in various fields.

The Electric Motor

The first problem was the electric motor that activates Luminoplastic 1, which had originally not been intended to run constantly. In an attempt to prevent further failures, we placed sensors that would activate the motor only when visitors approached the object. However, after a certain period, the motor stopped working. Conservators of modern art are well acquainted with the problem of obsolete technology and, with the goal of preserving the object’s function, it was decided not to adopt a “fetishist” approach (Citation: Muñoz Viñas 2005:90 [Muñoz Viñas, Salvador. 2005. Contemporary Theory of Conservation. Oxford: Elsevier, 49–105.]) to certain parts, because it was inevitable that they would have to be replaced. Srnec had used electric motors produced by the Bagat Company, which was very successful in the former Yugoslavia in the 1960s. Srnec mostly used two types of electric motor: Ruža and Danica. (Interestingly, the company had given women’s names to its various sewing machine models, most of which today sound old-fashioned.) A few years ago, when the electric motor of the second Luminoplastic object developed an irreparable failure, the former head of the conservation department, Zlatko Bielen, succeeded in finding one of these two motor types in a small shop. However, when the motor on Luminoplastic 1 stopped working in 2015, the original Ruža and Danica models were no longer available. An electrical engineer helped with the repair (the coil had burnt out), and it was thought that the motor would have a few years’ life left. Should an alternative to the existing motor be necessary, a replacement with a brushless motor and speed regulator was proposed, although the mechanics would need to be adapted. Also, one of the two leather belts within the construction needed to be replaced, as the material had split and lost elasticity over time, putting extra stress on the motor. We ordered a belt of the same diameter from a sewing machine supply shop, along with a replacement electric motor (for future use, if necessary) that had been made along the same principles as Ruža and Danica but produced in Taiwan.

Slide Projector and Slides: A Time-Based Media Issue

Further analysis of the construction elements showed that the artwork’s slide projector was not the original from 1967, as that one had burnt out during Srnec’s lifetime. On the advice of Srnec’s colleagues, the MSU acquired (around 2006) a new Kodak Ektalite 2000 analogue carousel slide projector, which is still in use today.

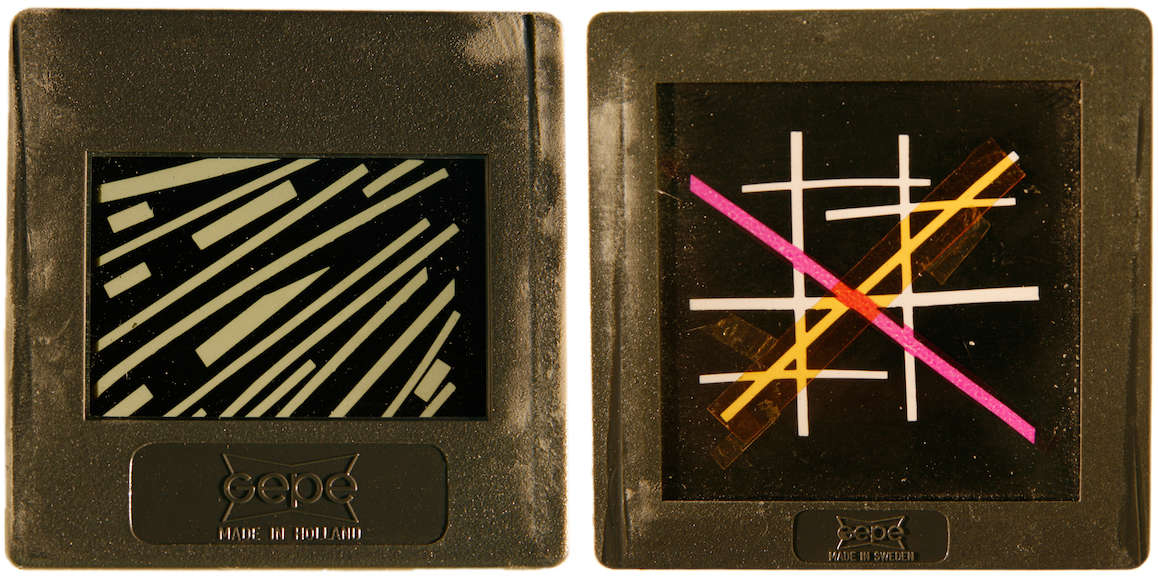

The eighty slides were examined with the assistance of a professional cinematographer,4 which led to several important pieces of information. The slides could be divided into two groups: those produced entirely by photographic means, and those on which the artist had intervened. Technically, they fell into four categories: collages, black-and-white graphic films, black-and-white graphic films with engraved drawings, and standard slides.

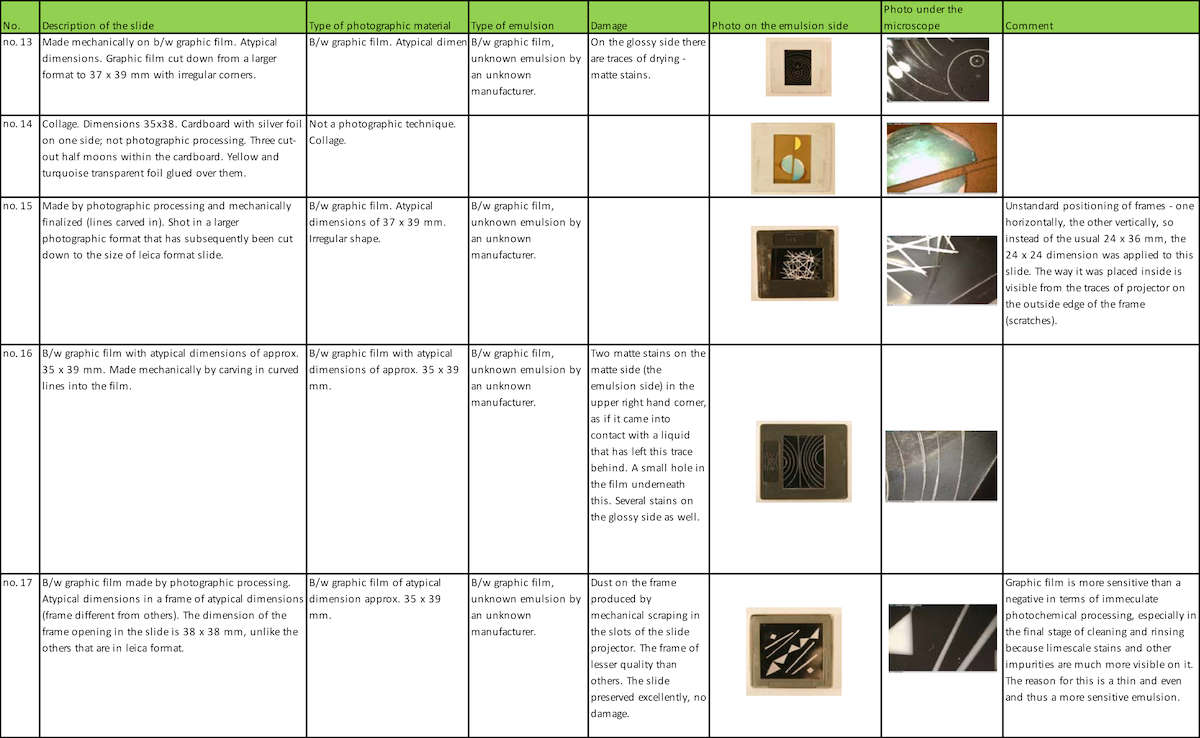

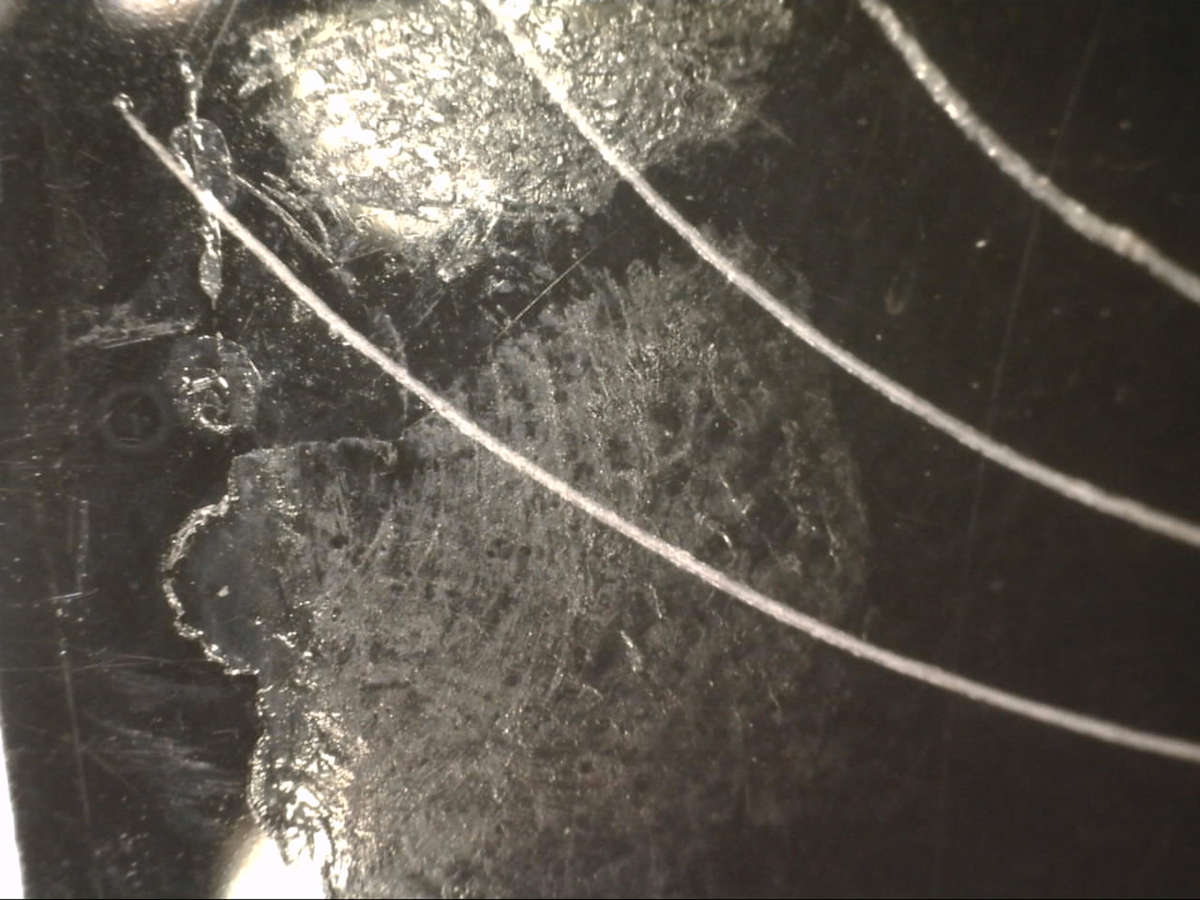

For documentary purposes, we used digital cameras to photograph each slide with its emulsion side face-up, and then examined them, emulsion side up, under a Dino-Lite microscope. The observations were described in detail in an Excel spreadsheet (fig. 8.7), including the condition as found, changes that had already occurred, and the technique and type of photographic material and emulsion used. The most obvious changes were irreversible spots on the emulsion, damage that had occurred because of the high temperatures of the projector’s lamp heat (fig. 8.8). The conservator, curator, and cinematographer decided that it was necessary to make exhibition copies of the slides. Although this decision launched ethical and technical discussions about the right way to proceed, there was immediate agreement that it was necessary to ensure a clear distinction between the originals and the exhibition copies. It is interesting to note that the need to protect the original slides had been acknowledged many years before and, at that time, a suggestion was put forth to make copies. Even setting aside the ethical aspect of this suggestion, it would have been difficult to achieve such a goal due to the imperfections of the originals and the tiny details that should be conserved. At the time, there was a good reason for the proposal.

So we decided to digitize the original slides guided by the premise of the acknowledged necessity of distinguishing between the original and replacement materials. The aim was to protect the originals by using digital files but also to respect the ethical principle of authenticity, “which forms the backbone of traditional conservation theory and practice” (Citation: Van Saaze 2013:36 [Van Saaze, Vivian. 2013. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artwork. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.]), as well as the performativity of this unique work of art. The correct preservation of digital files can markedly prolong the lifespan of an artwork.

Although Srnec did not originally use digital technology, creating analog exhibition copies of the slide-collages would cause a significant problem due to the difficulty of faithfully transferring the collages’ contents and all their details onto reversal film without altering their appearance.

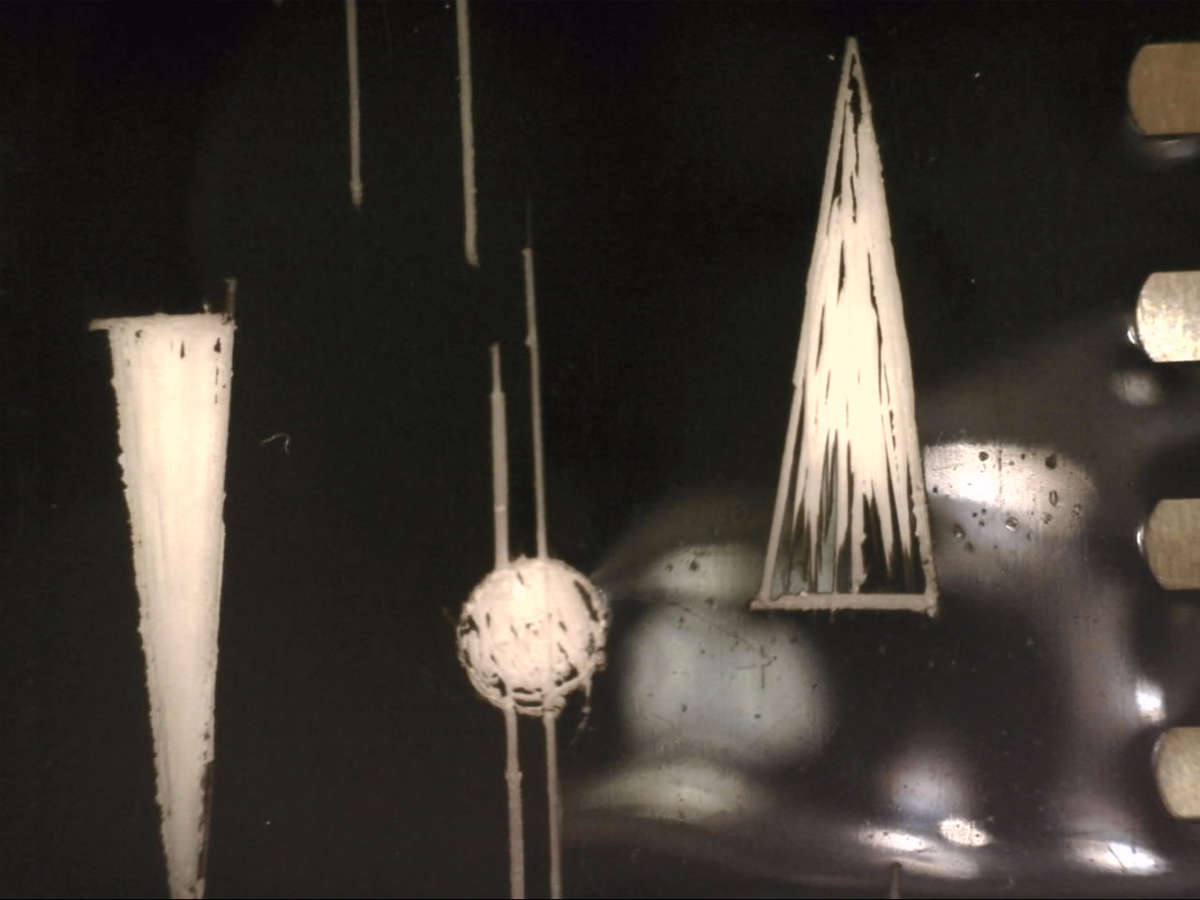

Digitizing the slides led us to the understanding that each one represented a separate work of art, which, had they belonged to another era, might have been called “miniatures.” They are abstract compositions in which one of the main motifs is lines that were created, using an engraving technique—scratching the surface of the film—which can clearly be related to Srnec’s early works from the early 1950s.

This series of compositions, on the border between geometric and lyrical abstraction, is interspersed by slides formed from geometric motifs—circles, triangles, cubes/squares—using a collage technique. These slides, which consist of transparent color film and silver candy wrappers, were difficult to scan due to their fragility, and due to the reflecting silver foil, which appeared black in the digital version. Additional Photoshop intervention was required to regain the appearance of silver foil (which in fact turns black during projection).

Luminoplastic 1 is a luminokinetic object that includes a time-based media element: the slide projection transforms it from a sculpture into a work with a performative aspect and ambience. Allographic art is an art form that is performed in some way, and this is a crucial dimension of Luminoplastic 1 (Citation: Goodman 1976:113 [Goodman, Nelson. 1976. Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Hackett.]). The artist’s hand is present in the slides, particularly those produced using a collage technique, and it is a very important feature of these works, giving them an autographic5 character. However, the secondary use of the slides, as projections in a new context, gives them an allographic character. Each slide is an individual work of art, but the projection has a certain duration, is variable, and gives a new dimension to the luminokinetic object.

Authenticity and change may be interpreted differently for autographic or allographic works of art, so the distinction between the two types of works is important when making conservation decisions (Citation: Laurenson 2006:8 [Laurenson, Pip. 2006. “Authenticity, Change and Loss in the Conservation of Time-Based Media Installations.” Tate Papers 6 (Autumn). Accessed April 1, 2016. http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/06/authenticity-change-and-loss-conservation-of-time-based-media-installations.]).

Scanning the slides on a flatbed scanner produced unsatisfactory results: it did not record all the details and imperfections, thus altering the slides’ original appearance. A rotary scanner was then used. Since the original slides had not been photographed or developed by a professional, they had a number of technical deficiencies that made them unique and reflected Srnec’s hand. This was particularly true where he engraved the film using a sharp object and for the collages made with candy wrappers and fixed with school glue, which had partially lost its adhesive properties. The slides were treated and conserved before the scanning process,6 which produced excellent results.7 While treating the slides, the issue of their order arose, but due to a lack of documentation, they were left in the order in which they were found.

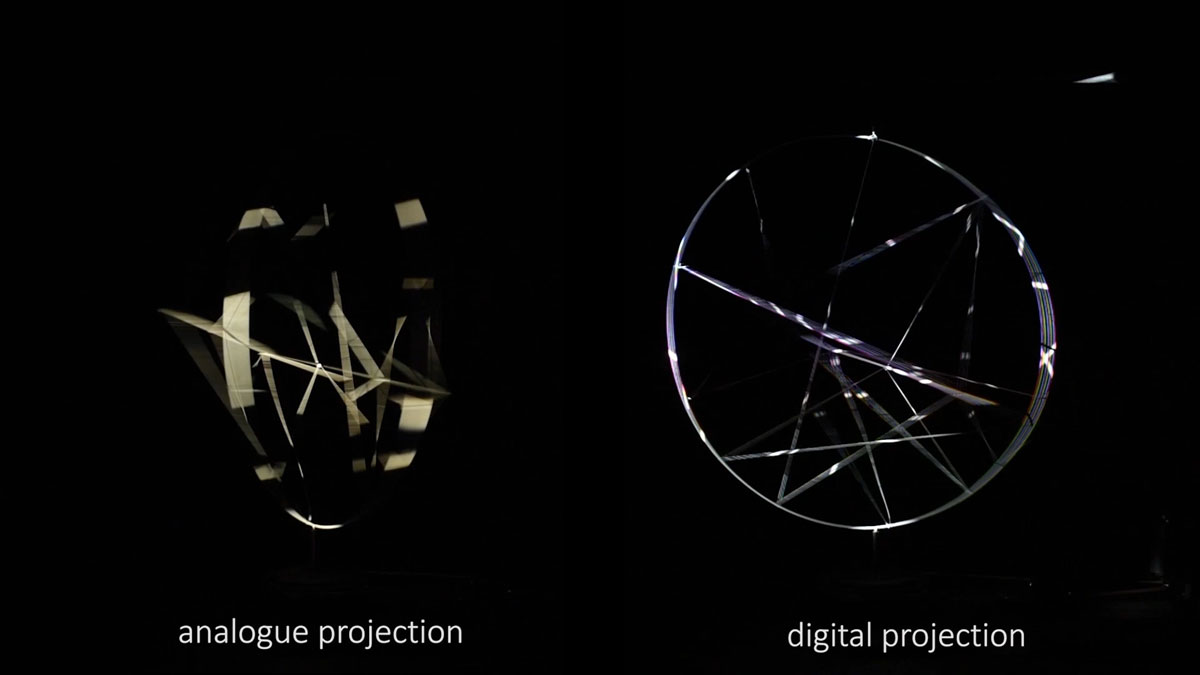

By comparing an analogue projection of the original slides (produced photochemically) and a digital projection of the scanned material, we discovered two differences that revealed two key problems. The first related to the range of colors. The analogue projection had warmer tones as a result of the Kodak projector bulb’s (halogen, tungsten filament) light temperature of 3,200 kelvin, in contrast to the cold, bluish light of the Osram Unishape lamp with Dynamic Dimming (approximately 6,500 kelvin) produced by the Texas Instruments projector, known commercially as DLP (Digital Light Processing) (fig. 8.9). During testing, a relatively acceptable result was achieved using a Kodak Wratten (KW) orange 85B filter. Any filter allows light to pass through it selectively, and this resulted in the visible reduction of some parts of the color spectrum. The KW 85B filter was only successful in the case of the black-and-white slides; for the chromatic slides (the collages), the desired result was not obtained.

The second problem was related to (timed) interruptions in the slide projection, which is a feature of any DPL projector. This technology creates projections in repeated sequences; first the red content of the image, then green, and then blue. When images are projected onto a moving object, the human eye perceives only the order of the red, green, and blue excerpts. This effect is sometimes perceptible even on fixed objects viewed on an ordinary projection screen as a series of separate colors, and the disturbance is known as the rainbow effect (fig. 8.10). When affected by movement, the image is also quite different from that projected by an analogue projector, and therefore needs improvement (fig. 8.11). In contrast to Texas Instruments’ DLP technology, the JVC company has developed LCoS (Liquid Crystal on Silicon) projection technology, which is not affected to the same degree by problems linked to the rainbow effect. This type of projector would achieve the desired result; however, it is expensive, and the MSU is still waiting for funds to purchase it.

Another option would have been to transfer the scanned slides onto film. In this case, the experts at the professional studio where the slides were scanned8 were willing to guarantee success in transferring black-and-white films and classic slides onto film, but could not offer a similar guarantee for the collages, as there was no standard procedure for obtaining absolutely faithful copies.

An additional complication in producing copies of the slides was the fact that the originals were probably not photographed, developed, and archived with an awareness of all the technical norms required to guarantee unquestionable slide quality. The noticeable departure from neutral, achromatic colors (white, gray) in the originals was probably the result of less-than-perfect photography and development; our photographic reproductions of the drawings, therefore, do not show white properly (the lines have a green tinge). Srnec, who was not a perfectionist in the technical sense, was probably not troubled by this departure from exact colors, so it was necessary for us to transfer these details faithfully onto exhibition copies. Each slide copy would be labelled accordingly during the process, so that the copy and the original could be clearly and easily distinguished.

Another option was to film Luminoplastic 1 in operation, and present it so that the nonfunctioning original would be on display next to a projected video of the functioning work. This has become standard practice in museum exhibitions in recent times. However, in that case, our work would have been a documentation of the original.

Considerations under Permanent Revision

Luminokinetic objects create a constantly changing space in which the idea of the artist—that is, the performativity of the artwork—is realized. Since context and function are crucial to their identity, it is difficult to focus solely on the material aspect during conservation and presentation.

The complicated interactions of integrity (Citation: Muñoz Viñas 2005:65–69 [Muñoz Viñas, Salvador. 2005. Contemporary Theory of Conservation. Oxford: Elsevier, 49–105.]), change, and the preservation of authenticity (Citation: Wharton and Molotch 2009:210 [Wharton, Glenn, and Harvey Molotch. 2009. “The Challenge of Installation Art.” In Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths, edited by Alison Richmond et al., 210–20. London: Elsevier, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum.]) require the museum profession to adopt a wide view of basic ethical principles and technical possibilities, so that these exceptional objects retain their true nature (Citation: Caple 2000:62 [Caple, Chris. 2000. Conservation Skills: Judgment, Method and Decision Making. New York: Routledge.]), identity, and accessibility to the public, for this is where their real value lies.

By asserting the distinction between originals and exhibited copies, which in the case of Luminoplastic 1 was guaranteed by the use of a new medium, the traditional approach was respected; that is, subjecting the work of art only to strictly necessary and minimal changes during conservation, preserving its integrity. Although the experience of observing interpretations in an old medium is quite different from doing so with today’s new media (for example, analogue vs. digital projection), any divergence that results from transforming works into digital media can be justified when one respects the traditional distinction between the original material and the use of additional material for conservation and restoration. Luminoplastic 1 is nonetheless a unique physical object and, as with many other kinetic works, its materials and construction are firmly associated with the period in which it was made. As objects age, they create challenges and debates regarding their identity.

As a multimedia artist, Srnec was motivated by creative curiosity, saying, “I have given most of my works to friends. I did not see any value in them. Value for me was explaining something to myself.”9

The interpretative role of museum professionals who are entrusted with showing a work of art is undeniable. With contemporary art, there are moments when the conservator and curator become participants in the artist’s intentions, as Vivian van Saaze explains:

Rather than being a facilitator or “passive custodian,” the curator or conservator of contemporary art can be considered to be an interpreter, mediator or even a (co-)producer of what is designated as “the artist’s intention” (Citation: Van Saaze 2013:33 [Van Saaze, Vivian. 2013. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artwork. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.]).

This highlights the responsibility that all museum professionals have in deciding how to show a work of art so that its meaning is interpreted faithfully.

Notes

- Citation: Kolešnik 2012 [Kolešnik, Ljiljana. 2012. “Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern Art.” In Socialism and Modernity: Art, Culture Politics 1950–1974, edited by Ljiljana Kolešnik, 107–80. Zagreb: Institute of Art History, Zagreb, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb.]. The robustness of this period in art led to five exhibitions entitled New Tendencies held in Zagreb between 1961 and 1973, organized by what is today the MSU. In fact, some of the museum’s most important holdings are the works of art and archive documentation produced by the New Tendencies participants. ↩

- Srnec, in Gordana Brzović and Kristina Leko’s documentary Aleksandar Srnec (2000), 57 min. ↩

- The MSU was originally the Gallery of Contemporary Art, and it was housed in a baroque palace with a rather small space (400 m2) used only for temporary exhibitions. The new building finally provided appropriate space for the permanent display. ↩

- The authors are grateful to Krešo Vlahek for his expert assistance. ↩

- Citation: Goodman 1976:113 [Goodman, Nelson. 1976. Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Hackett.] calls art forms such as painting and etching “autographic” arts: “a work of art is autographic if and only if the distinction between original and forgery of it is significant; or better, if and only if even the most exact duplication of it does not thereby count as genuine.” ↩

- Technical characteristics: scan resolution 660 dpi. ↩

- The rotational scanner creates high-quality files with resolutions ranging from 2,400 to 9,600 dpi, in contrast to flatbed scanners, which can reach a maximum resolution of 1,200 dpi. A digital file scanned on a rotational scanner deviates only minimally from its template. ↩

- Skaner Studio, Stubička 49, Zagreb, Croatia. ↩

- Srnec, in Gordana Brzović and Kristina Leko’s documentary Aleksandar Srnec (2000), 57 min. ↩

Bibliography

- Ashley-Smith 2009

- Ashley-Smith, Jonathan. 2009. “The Basic of Conservation Ethics.” In Conservation Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths, edited by Alison Richmond et al., 6–21. London: Elsevier, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum.

- Bek 1969

- Bek, Božo, ed. 1969. Tendencije 4: Zagreb, 1968–1969. Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. Exh. cat.

- Caple 2000

- Caple, Chris. 2000. Conservation Skills: Judgment, Method and Decision Making. New York: Routledge.

- Denegri 2004

- Denegri, Jerko. 2004. Constructive Approach Art: Exat 51 and New Tendencies. Zagreb: Horetzky.

- Goodman 1976

- Goodman, Nelson. 1976. Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Kolešnik 2012

- Kolešnik, Ljiljana. 2012. “Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern Art.” In Socialism and Modernity: Art, Culture Politics 1950–1974, edited by Ljiljana Kolešnik, 107–80. Zagreb: Institute of Art History, Zagreb, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb.

- Laurenson 2006

- Laurenson, Pip. 2006. “Authenticity, Change and Loss in the Conservation of Time-Based Media Installations.” Tate Papers 6 (Autumn). Accessed April 1, 2016. http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/06/authenticity-change-and-loss-conservation-of-time-based-media-installations.

- Muñoz Viñas 2005

- Muñoz Viñas, Salvador. 2005. Contemporary Theory of Conservation. Oxford: Elsevier, 49–105.

- Muñoz Viñas 2010

- Muñoz Viñas, Salvador. 2010. “The Artwork Became a Symbol of Itself: Reflections on the Conservation of Modern Art.” In Theory and Practice in the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art, edited by Ursula Schadler-Saubed et al., 9–19. London: Archetype.

- Van Saaze 2013

- Van Saaze, Vivian. 2013. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artwork. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wharton and Molotch 2009

- Wharton, Glenn, and Harvey Molotch. 2009. “The Challenge of Installation Art.” In Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths, edited by Alison Richmond et al., 210–20. London: Elsevier, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum.