4. Conserving Thomas Wilfred’s Lumia Suite, Opus 158

- Carol Snow

- Lynda Zycherman

Abstract

Thomas Wilfred: The Unrecognized Pioneer

Thomas Wilfred (1889–1968) was born Richard Edgar Løvstrøm in Naestved on the island of Zealand, Denmark. In Copenhagen, as a precocious sixteen-year old, he began experimenting with light as an artistic medium, using a cigar box, incandescent light, and colored glass to create colored projections. Later, when he studied painting at the Sorbonne, he expanded his setup to several cardboard boxes, lenses, and a bedsheet screen. His painting instructor discouraged him from pursuing his experimentation with light, directing him toward traditional painting instead; yet Wilfred persevered with his passion undaunted. During his early, experimental years as a light artist, Wilfred supplemented his income by performing medieval music on the archaic, twelve-string archlute; he performed to international acclaim until 1914, when he was called to duty in World War I. After his service, he immigrated to the United States in 1916 to continue his experiments with light art and work out its presentation to the public. By 1919 he abandoned his career as a musician to devote himself to the art of light.

Artists and musicians from the sixteenth through the early nineteenth centuries had dreamed of seamlessly marrying color and sound in a single instrument,1 usually called a “color organ” or, more elaborately, a kaleidoscope, clavier à lumières, Chromola, Optophonic Piano, Sarabet, and Chromopiano, each of which joined music with light projections. Most often, a single performer played the music and coordinated the light, but there are orchestral scores combining light projections and music.2 Like all of the other precursors and presentations by contemporaneous artists who worked with projected light, this presentation relied on at least one performer.3 However, Wilfred’s unique contribution was to present kinetic colored light performances without the music: a silent, purely visual experience.4

By 1919, after years of experimentation, Wilfred invented his own color organ, calling it the clavilux, from the Latin clavi (key) and lux (light), thus “light played by key.” To the traditional seven arts—architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry, dance, and theater—Wilfred added an eighth, lumia, his term for signifying light as its own expressive art form. The light was not in the art; the light was the art.

To Wilfred, lumia, in addition to being a general term for an art form, were compositions played on claviluxes. Wilfred’s clavilux was different from other color organs of the time because it created shapes of colored light by means of reflectors, diaphragms, and stained-glass disks, and the shapes moved silently across the screen.

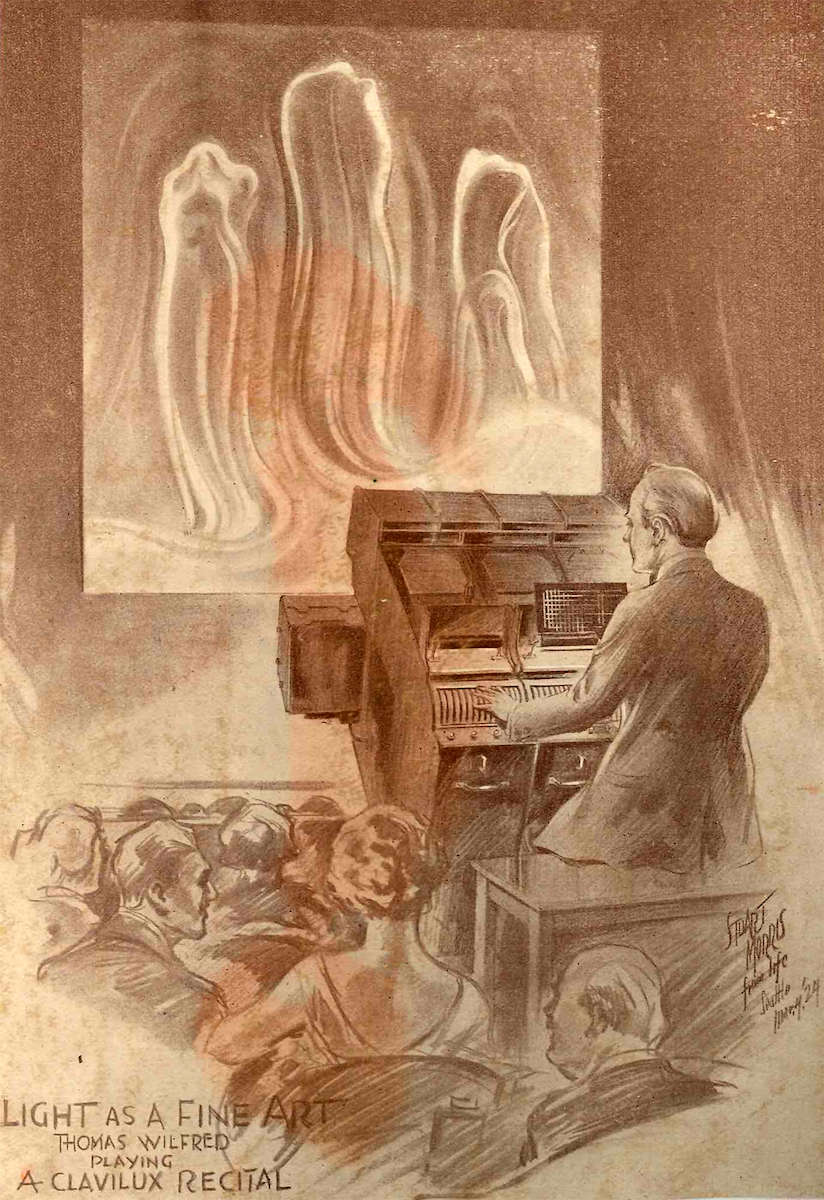

Wilfred had perfected his first clavilux by 1921, and the next year had his first ticketed public performance, at the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York City, which was followed by worldwide tours from 1922 to 1925, to generally favorable reviews (fig. 4.1). Theater and film producer Kenneth Macgowan wrote, “This is an art for itself, an art of pure color; it holds its audience in the rarest moments of silence that I have known in a playhouse” (Citation: Wilfred 1947:250–51 [Wilfred, Thomas. 1947. “Light and the Artist.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 5, no. 4: 247–55.]). His setup at every venue was similar: a large screen placed at center stage, the artist seated downstage at a clavilux console with his back to the audience. Because this was a new art form, the audience members had no preconceived ideas about what they were going to experience, and sitting in silence for an hour, watching something large on a screen, would probably not have been uncomfortable. In 1927—the same year that talking films were first produced—Wilfred positioned himself to the side of the stage behind a curtained enclosure, to allow the audience to concentrate on the visual without the distraction of the clavilux operator.

In the first part of the twentieth century, it would have been unusual to have someone perform in galleries devoted to paintings. And how would such works have entered private collections? Wilfred addressed these thorny issues by developing a clavilux that no longer required an operator for performances. By 1928 Wilfred created his first internally programmed clavilux, a projector that could play lumia compositions by itself. Two years later he founded the Art Institute of Light in New York City as a nonprofit entity for research on lumia. Soon after, an article in the New York Times reported on his invention of a new kind of painting with light as a medium that could be displayed at home like a painting. Wilfred said about the quality and permanence of lumia: “These pictures are built up in three dimensions as a sculptor shapes a statue. They have a depth impossible to attain with oils or watercolors, and furthermore they are imperishable, since the colors are fused in glass.”5 In 1933 Wilfred opened a theater with surrounding studios and laboratories in Grand Central Palace, a performance hall above New York’s Grand Central train station (Citation: Wilfred 1947:251 [Wilfred, Thomas. 1947. “Light and the Artist.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 5, no. 4: 247–55.]).

Wilfred’s Exhibitions

From the 1930s until his death in 1968, Wilfred continued to create and advocate for his lumia as the eighth art form, always feeling unappreciated because museums did not buy his work (with the exception of MoMA’s 1942 purchase), and private collectors, however enthusiastic, were a small group. A 1959 commission for the Clairol headquarters in New York seems to have been his first and last relationship with a corporate collection. In 1967 he showed with Nam June Paik at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York; by this time a new era of time-based media art had begun, but Wilfred, a prime innovator, was neither featured nor given credit for his farsighted inventions.

In 1971, three years after Wilfred’s death, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., organized a retrospective exhibition of eleven internally programmed lumia compositions that were completely self-operating in addition to twenty-eight drawings, dating to 1928, that represented technical ideas, individual works, and visionary projects and designs for theatrical projected light settings. A smaller version of the exhibition traveled to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

Nearly forty years after Wilfred’s death, his lumia were shown in the 2005 exhibition Visual Music: 1905–2005 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Wilfred’s final composition, Lucatta, Opus 162, was exhibited alongside works by Lynda Benglis, Robert Indiana, and Jimi Hendrix, to name a few, at the 2005–7 exhibition Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era.6 In 2011 director Terrence Malick used Wilfred’s 1965 composition, Opus 161, in his film The Tree of Life.

At present, there are lumia compositions in collections across the United States, from New Haven to Honolulu, yet only Wilfred’s final work, Lucatta, Opus 162, remains on view as a loan to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; all other extant works have been allocated to museum storage, are in private collections, or have been lost. We express gratitude to passionate lumia collectors and mechanical experts Eugene Epstein and A. J. Epstein, who have saved, preserved, and restored numerous works by Wilfred and made nearly every recent exhibition of Wilfred’s oeuvre possible.

Wilfred and the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Wilfred’s long-awaited major breakthrough in the museum world came in 1942, when MoMA purchased his Vertical Sequence II, Opus 137 (1941),7 his first lumia composition to enter a museum collection. A decade later, MoMA further advanced Wilfred’s career by including him in the exhibition 15 Americans (1952) alongside fourteen other artists: William Baziotes, Edward Corbett, Edwin Dickinson, Herbert Ferber, Joseph Glasco, Herbert Katzman, Frederick Kiesler, Irving Kriesberg, Richard Lippold, Jackson Pollock, Herman Rose, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Bradley Walker Tomlin. An outlier in the exhibition of eleven painters and three sculptors, Wilfred was nonetheless appreciated by some as the only truly original artist in the exhibition (Citation: Turrell 2013 [Turrell, James. 2013. “James Turrell with Alex Bacon.” The Brooklyn Rail, September 4. Accessed August 27, 2016. http://www.brooklynrail.org/2013/09/art/james-turrell-with-alex-bacon.]). In 1961 MoMA acquired a second Wilfred, Aspiration.8 Both are domestically sized, internally programmed lumia compositions shown in wooden cabinets, with small screens (approximately 38 × 38 cm), a far cry from the giant, projected images of the concert stage.

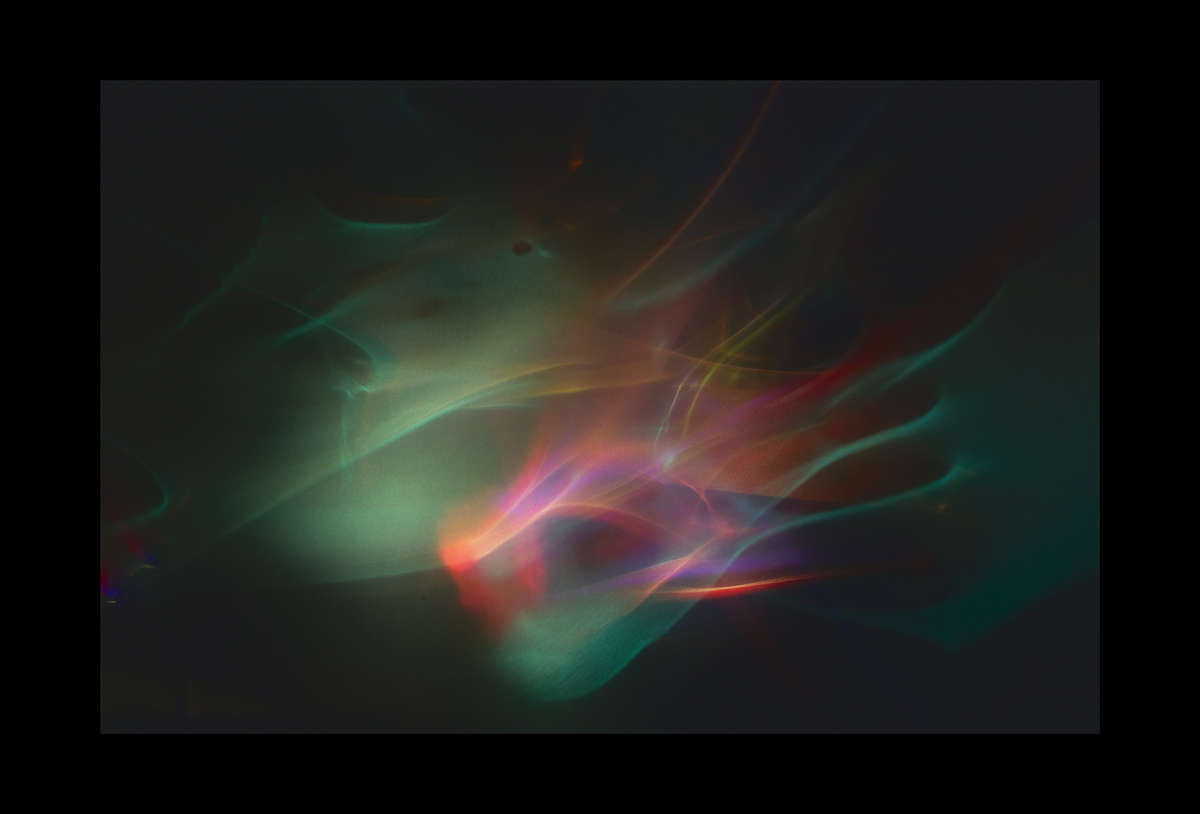

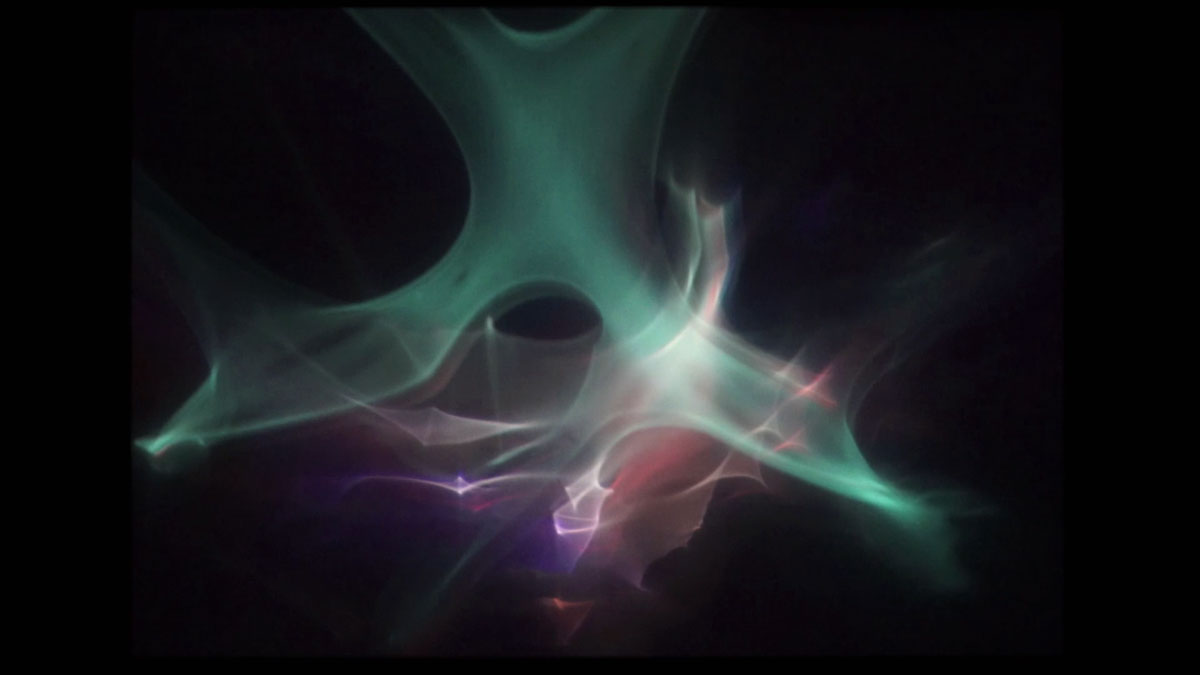

In 1963 MoMA again supported Wilfred by commissioning a new installation for its thirty-fifth anniversary and 1964 reopening of renovated and expanded galleries designed by Philip Johnson. In a return to the lumia as large works suitable for public spectacle, Wilfred created his magnum opus, Lumia Suite, Opus 158 (fig. 4.2).9 In a custom-designed, 3.6 × 4.8 m room painted dark gray, viewers sat on custom benches centered before a 2.4 × 1.8 m screen with a rear-projected moving-light spectacle. The installation was a favorite of the public, and it ran nearly continuously for seventeen years.

When MoMA closed its galleries for the 1981–84 expansion of its campus, Lumia Suite was dismantled and carefully stored. (fig. 4.3). It remained in storage until December 2014, when the Yale University Art Gallery requested Lumia Suite for its 2017 exhibition Lumia: Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light, in which fifteen kinetic light works dating from 1928 to 1968 would be on view. Having Lumia Suite in working order was essential; without it, there would be no exhibition.

Resurrecting Wilfred’s Lumia Suite, Opus 158

After unpacking the numerous crates and boxes sent by MoMA to Yale in early 2015, eighty-five items, ranging from Wilfred’s tools to spare sheets of mica, were catalogued into the database and tracked with barcodes. It took days to sort the main components for Lumia Suite from the spare parts and hardware, but it led to a better appreciation of Wilfred’s foresight in guaranteeing that his lumia would last into the future. In correspondence to MoMA, Wilfred stated: “It will probably be a long time before any of the spare items will be needed, and by that time the manufacturers may have changed their models and replacements may take a long time.”10 The Rosetta stone among all of the items was Wilfred’s technical manual, written for the museum conservator at MoMA and staff of the Art Institute of Light, without which the resurrection of Lumia Suite would not have been possible (Citation: Wilfred 1964 [Wilfred, Thomas. 1964. “Lumia Suite, Op. 158 by Thomas Wilfred 1964. Lumia Composition in 3 Movements: A technical manual on the projection instrument rendering the composition, as installed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City during June and July, 1964.” Museum Collection Files, Thomas Wilfred, Lumia Suite, Opus 158. Department of Painting and Sculpture, Museum of Modern Art, New York.]).

A thorough condition assessment of the main components was performed: vertical projector, horizontal projector, reflector tower, elliptical convertor, two ultramarine flood lamps, lamp control unit, and the actuator. An important part of this assessment was checking the condition of the 1960s electrical wiring and testing the electrical components. A multimeter, an instrument that measures electric current, voltage, and resistance, was used to check all switching devices, motors, and fans. The electrical components of Lumia Suite looked good, including the hazardous asbestos wiring and mercury switches. Minor physical damage was discovered—the color wheel on the vertical projector was bent out of plane and the adhesion of some electrical tape had failed—but otherwise Lumia Suite was in robust condition.

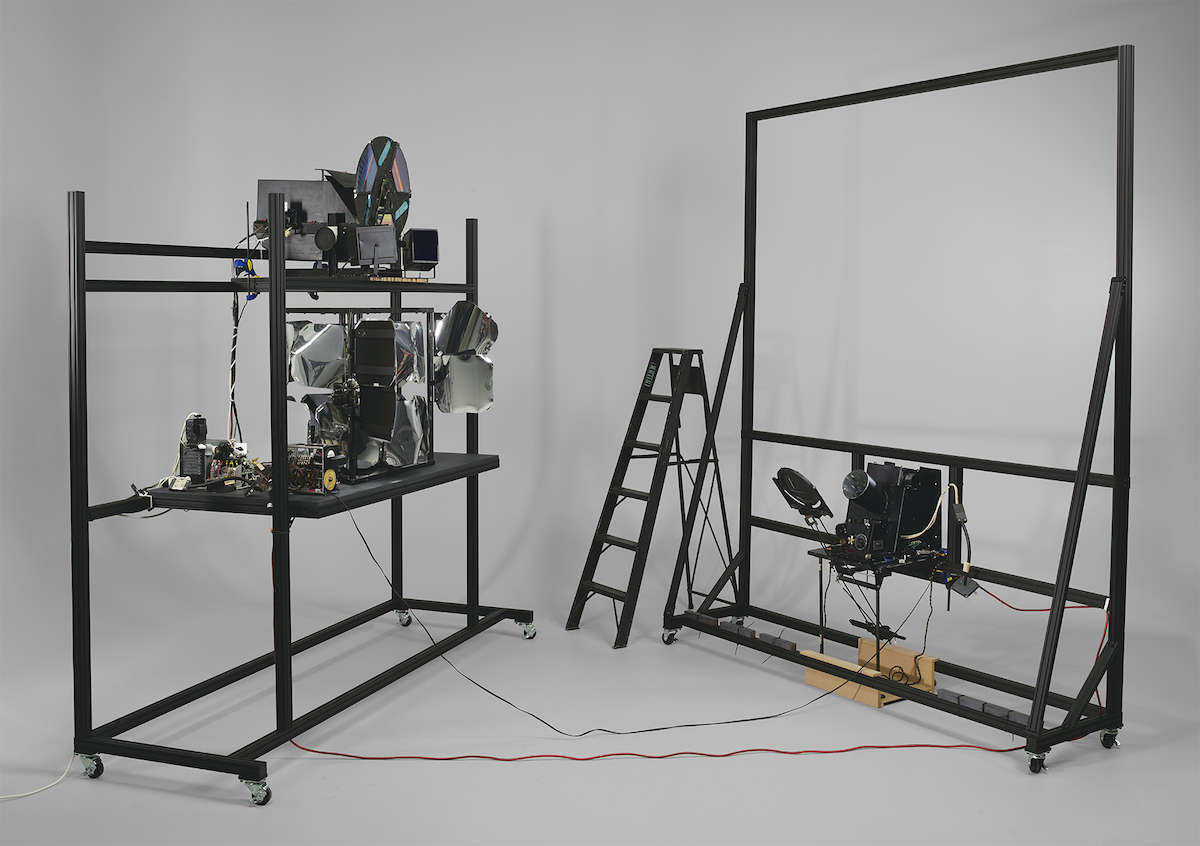

The next phase of the project was the design and construction of a portable system to replace MoMA’s original projection room, which had been built with lumber, drywall, and a firewall. Again, Wilfred’s meticulous descriptions, along with his scale drawings (¼ in.:1 ft. and 1 in.:1 ft.), allowed for accurate reconstruction and reassembly (fig. 4.4). A T-slotted, anodized matte-black (to prevent light reflections), extruded aluminum track system was chosen to provide two lightweight, adjustable, and mobile framework systems to replace the opposing walls in the projection room. While the 80/20 aluminum frames were being fabricated, treatment of the components proceeded.

All main components were cleaned, as per Wilfred’s instructions: glass was cleaned with alcohol (ethanol), and the aluminum reflectors were cleaned with a soft brush. The metal, glass, and theater-gel color wheel for the vertical projector was carefully put back in plane through gentle clamping. As it turned out, very little treatment was required, and our intent was to keep all original parts as long as they were safe to reuse.

With the aluminum frameworks ready to receive the components, and the components ready to be installed, reassembly could proceed (fig. 4.5). The components were placed in their precise locations relative to one another, and their electrical connections were made following Wilfred’s wiring diagrams and explanations. At this stage, there was still no way of knowing if the contacts and communications among all parts would still work as a unified whole. The wiring within the walls at MoMA had included a main electrical panel, but to simplify the exhibition’s installation at the Yale University Art Gallery and its subsequent appearance at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (October 2017–January 2018), heavy-duty extension cords were used for the initial setup. Because this work was being done in the conservation laboratory of the new Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage at Yale, the most up-to-date electrical codes had been used, following the National Electrical Code (NEC) as part of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), as well as elevated requirements from the Yale Environmental Health and Safety Department. Problems were unlikely because the alternating current (AC), 120V power supply of the 1960s had been upgraded to a much higher level of safety in the 1970s. Regardless, the nearby circuit panels were monitored and a fire extinguisher was kept next to Lumia Suite while the main components were plugged in.

The technical manual described the importance of the timing and synchronization of all components, so although brief tests were conducted on individual components, the installation was not plugged in for any length of time until all components were wired together as per Wilfred’s instructions. Once completely connected, Lumia Suite was plugged in simultaneously using one extension cord for the light bulbs and lamps and one extension cord for all motors and fans. That way all components were synchronized and followed precisely the twelve-minute cycle comprising the three movements: horizontal, vertical, and elliptical. The only components that needed to be replaced during the electrical setup were one small potentiometer that controlled the motion of the elliptical convertor and one 5 amp fuse in the lamp control unit, both still readily available. A thermal check with a FLIR ONE camera attachment for smartphones confirmed that the source of the greatest heat was the 1,000W beacon bulb in the horizontal projector (fig. 4.6).

In the technical manual, Wilfred describes the precise type of 1,000W beacon bulb (now obsolete) that must be used, and the alignment of its tungsten filament. The loan agreement with MoMA stipulated that the few remaining original light bulbs, including the extras they have from 1964, not be used during the exhibition. After searching for available alternatives and testing new technologies such as LED and halogen 1,000W bulb equivalents, it was decided that a more exact replica could only be obtained by hand manufacturing. Dylan Kehde Roelofs, an incandescent light artist who trained as a chemical glass blower, was invited to Yale to consult on this issue. Roelofs first produced a much smaller wattage bulb in the Yale chemical glassblowing laboratory and believed, after some research and development, that he could produce a suitable 1,000W bulb matching as closely as possible the filament of the original General Electric 1M/T 20 P/AB bulb (fig. 4.7). He created two prototypes bulbs within a few months. The first prototype was kept burning for more than 500 hours, and was then put on a timer that turned it on and off every thirty minutes, as it is the on/off cycle that causes the most wear on tungsten filaments. After an additional 300 hours of burning, the clamp device holding the bulb failed and the bulb fell and broke on the concrete floor. Microscopic examination of the filament, however, revealed it was still burning when it broke: blue tungsten oxide (W18O49) crystals, which form around 700˚C, were evident. The tests far exceeded all expectations of the handmade bulb’s performance, and twenty more light bulbs were ordered at a cost of $250 per bulb.

Because the original Colorwall 30 rear projection screen provided by the Trans-Lux Corporation was deteriorated, yellowed, and brittle, a replacement screen had to be made. It is possible that the original was made from natural latex. Trans-Lux has agreed to search its archives and try to find a suitable replacement. New materials are available that increase the sharpness of the image and angle of focus, qualities that may be necessary in museum-gallery lighting conditions, where some ambient light is required for visitor safety. Research into rear projection screens continued as this paper went to press, but during treatment a sheet of high-density polyethylene was used for a temporary screen (fig. 4.8).

A critical part of any treatment of kinetic art is documentation that includes high-resolution video. The Yale University Art Gallery is planning to do additional still-image and video documentation once an acceptable new screen is chosen. Simultaneous with the high-resolution video, several twelve-minute cycles of the work will be captured using multiple video cameras. Behind the screen, video cameras will film the mechanics of the various moving parts that create the projected image. Though Wilfred may not have approved of our revealing the interior kinetic components that produced his lumia, this may be the only opportunity to document Lumia Suite, Opus 158 from the inside out (fig. 4.9).

Wilfred’s groundbreaking contribution to kinetic art and time-based media is finally being reevaluated through a long-awaited retrospective in 2017 and the scholarly consideration that accompanies such an endeavor. The exhibition would be impoverished without the inclusion of Wilfred’s magnum opus, Lumia Suite, Opus 158. Our conservation and restoration of the physical and electrical components of this masterwork allow it to be safely exhibited for the first time in more than three decades, and the small upgrades ensure that the installation can be enjoyed long into the future.

Materials and Suppliers

Extruded aluminum: manufactured by 80/20 Inc., https://www.8020.net; distributed by AIR, Inc., http://airinc.net/8020-extrusion.

Handmade tungsten-filament incandescent light bulbs: Dylan Kehde Roelofs, http://www.incandescentsculpture.com.

Coiled tungsten filaments: R. D. Mathis, Long Beach, CA, http://www.rdmathis.com.

Infrared camera for smartphone: FLIR ONE, http://www.flir.com.

Notes

- For a chronology of the idea and its various incarnations, see “Color organ,” Wikipedia, accessed November 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_organ. ↩

- Most notable among these is Russian composer Alexander Scriabin’s synesthetic symphony Prometheus: The Poem of Fire (1915), re-created in February 2010 by Anna Gawboy, a doctoral candidate at the Yale School of Music and scholar of Scriabin. See Yale Broadcast & Media, “Scriabin’s Prometheus: Poem of Fire,” 2010, accessed November 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3B7uQ5K0IU. ↩

- Film is excluded because it is not a direct projection of colored light. ↩

- Alice Armstrong, “Explorations in Light: Affinities of Color and Music,” American Arts Quarterly 26, no. 1 (Winter 2009), available online at Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center, accessed November 2016, http://www.nccsc.net/legacy/explorations-in-light. Wilfred was vehemently opposed to using music in his lumia: “Mr. Wilfred’s clavilux has no connection with electronic instruments designed to transcribe sound or musical chords into color. ‘The musical analogy is a lost cause,’ he says. ‘Sound and color are simply not equivalents.’” See Grace Glueck, “New Art Display ‘Plays’ On and On,” New York Times, July 11, 1964, 22, in which Glueck interviews Wilfred and reviews his Lumia Suite, Opus 158, commissioned for the Museum of Modern Art. ↩

- “New Kind of Painting Uses Light as Medium,” New York Times, December 8, 1931, 34. ↩

- Organized and presented by the Tate Liverpool, the exhibition traveled to the Kunsthalle Schirn Frankfurt, Kunsthalle Wien, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. ↩

- MoMA accession number 166.1942. ↩

- MoMA accession number 133.1961. ↩

- MoMA accession number 582.1964. ↩

- Thomas Wilfred, letter to MoMA curator Dorothy Miller, January 6, 1965. Museum Collection Files, Thomas Wilfred, Lumia Suite, Opus 158. Department of Painting and Sculpture, Museum of Modern Art, New York. ↩

Bibliography

- Farmer 1920

- Farmer, Virginia. 1920. “Mobile Colour: A New Art.” Vanity Fair (December): 53, 116.

- Turrell 2013

- Turrell, James. 2013. “James Turrell with Alex Bacon.” The Brooklyn Rail, September 4. Accessed August 27, 2016. http://www.brooklynrail.org/2013/09/art/james-turrell-with-alex-bacon.

- Wilfred 1947

- Wilfred, Thomas. 1947. “Light and the Artist.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 5, no. 4: 247–55.

- Wilfred 1964

- Wilfred, Thomas. 1964. “Lumia Suite, Op. 158 by Thomas Wilfred 1964. Lumia Composition in 3 Movements: A technical manual on the projection instrument rendering the composition, as installed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City during June and July, 1964.” Museum Collection Files, Thomas Wilfred, Lumia Suite, Opus 158. Department of Painting and Sculpture, Museum of Modern Art, New York.