3. Fast and Furious: Operation, Maintenance, and Repair of Chris Burden’s Metropolis II at LACMA

- Mark Gilberg

- Alison Walker

- Richard Sandomeno

Abstract

Introduction

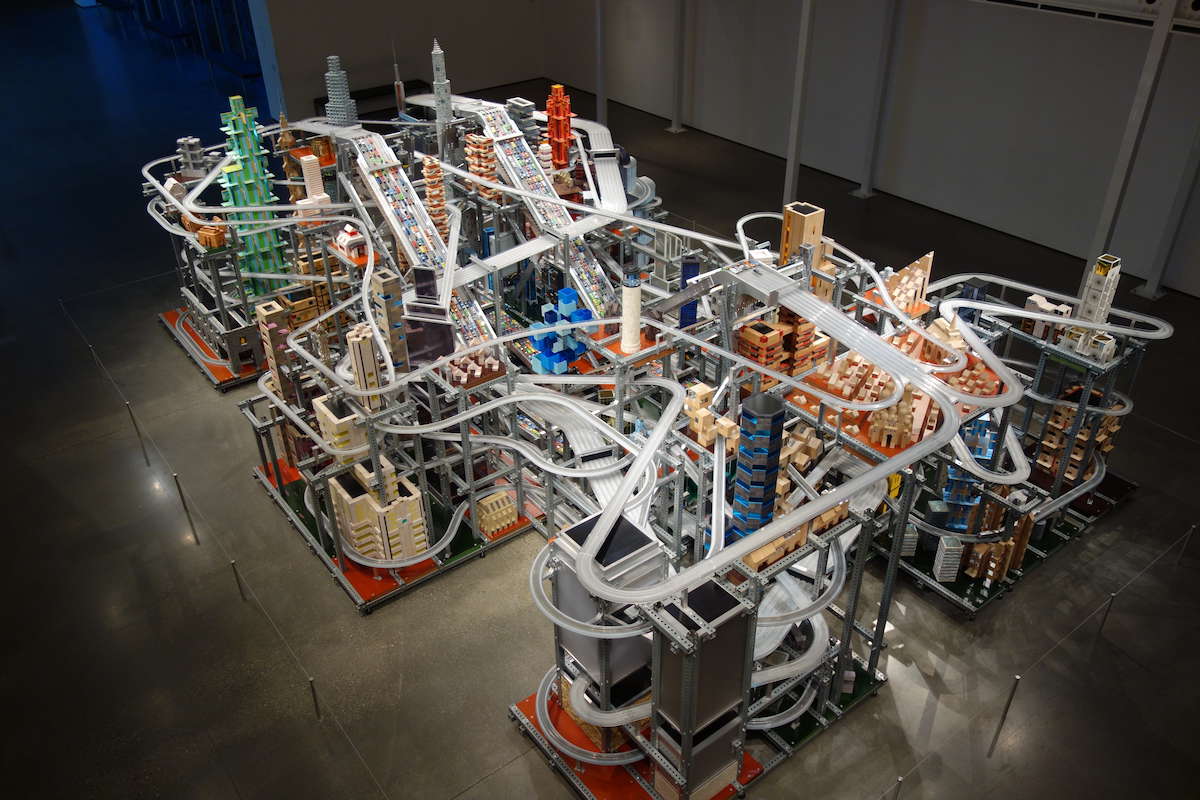

Artist Chris Burden (1946–2015) designed and fabricated Metropolis II (2011), an intense kinetic sculpture modeled after a frenetic modern city (fig. 3.1). Steel tubing (Unistrut) forms a structural grid interwoven with an elaborate system of eighteen roadways, including a six-lane freeway, and HO-scale1 train tracks. Miniature cars speed through the city at 240 scale miles per hour; every hour, the equivalent of approximately 100,000 cars circulates through the sculpture’s dense network of buildings. According to Burden, “The noise, the continuous flow of the trains, and the speeding toy cars produce in the viewer the stress of living in a dynamic, active and bustling 21st century city” (Citation: Schader 2012 [Schader, Susan. 2012. “‘It exists.’ Artist Chris Burden on Metropolis II.” Words & Images (blog). November. http://sschader.blogspot.com/2012/11/it-exists-artist-chris-burden-on.html.]). Burden described its fabrication as a “string and felt tip pen operation”; that is, no computer renderings or plans were used (Citation: Schader 2012 [Schader, Susan. 2012. “‘It exists.’ Artist Chris Burden on Metropolis II.” Words & Images (blog). November. http://sschader.blogspot.com/2012/11/it-exists-artist-chris-burden-on.html.]). The sculpture took five years to build, and the development of the architecture was very organic, with Burden in the studio every day making aesthetic decisions. Purchased by the Nicholas Berggruen Foundation, Metropolis II is on loan through 2022 to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and it has been on display and in continuous operation since January 2012. It took almost three months to disassemble the sculpture and four and a half months to install at LACMA.

We discuss the exhibition of this contemporary sculpture, focusing on specific maintenance and repair issues—foreseen and unforeseen—that illustrate many of the problems inherent to the acquisition and operation of kinetic works of art. We examine LACMA’s overall philosophy and approach to the operation and maintenance of Metropolis II, including the repair and replacement of damaged parts, in the context of both the artist’s and the owner’s expectations as well as the demands of the museum’s exhibition program. We also focus on the costs associated with the sculpture’s long-term operation and how best to assess the artwork’s condition and predict or anticipate mechanical failure.

Metropolis II

When installed, the sculpture is approximately 6.4m wide by 9.1m long (fig. 3.2); it is approximately 3m tall at its highest point. The main structure of the sculpture breaks apart into nine separate sections, or modules, which connect via telescoping steel tubing (Unistrut). Each module is designed to fit into a shipping container for ease of transport. The core module houses the three conveyor systems, including their motors, conveyor belts, conveyor ramps, and associated control devices that operate the sculpture. Each module has leveling feet (eighty-six total) that are used to calibrate the sculpture and align the tracks on adjacent modules. All car and train tracks bridging adjoining modules, which number more than 100 pieces, must be removed for the deinstallation/installation process.

At any given time, there are 1,200 cars in operation on the sculpture. The ninety-six custom car types—four body types, each type in four colors, and six combinations of detailing within each color scheme—were mass-produced in China after extensive prototyping at Burden’s studio. Each car is die-cast aluminum with a rare-earth magnet embedded in its chassis, and each has front and back rubber bumpers to dampen the impact as the cars run into one another at the bottom of the conveyor ramps. Each of the three conveyor ramps is a six-lane highway, and each has a corresponding conveyor belt with magnets embedded in it (fig. 3.3). When the conveyor motor is on and the conveyor belt is moving, the attraction between the belt and car magnets draws the car to the top of the ramp. Once the car is at the top, the conveyor belt loops away and gravity causes the car to fall down the track until it hits the cars that have stopped at the base of the ramp. It is this push from behind that engages the conveyor belt and draws the car back to the top again.

The speed of the cars is controlled by a series of adjustable brushes installed over the car track. Located at various strategic points along the roadways, particularly near curves, these brushes can be lowered or raised to alter the amount of friction on the car as it passes underneath them.

There are also thirteen electric trains on Metropolis II, eight loops with train sets and five end-to-end trolleys (fig. 3.4). The store-bought trains and trolleys are HO scale (approximately 1:87), and they were specifically chosen by the artist for their aesthetic qualities. Each train track has its own controller, allowing the operator to individually adjust the speed of the trains as specified by the artist. Each trolley track has an optical sensor (a tiny, light-sensitive photocell) at each end. When the moving trolley gets close to the optical sensor, blocking the light, a signal is sent for the trolley to stop and reverse direction.

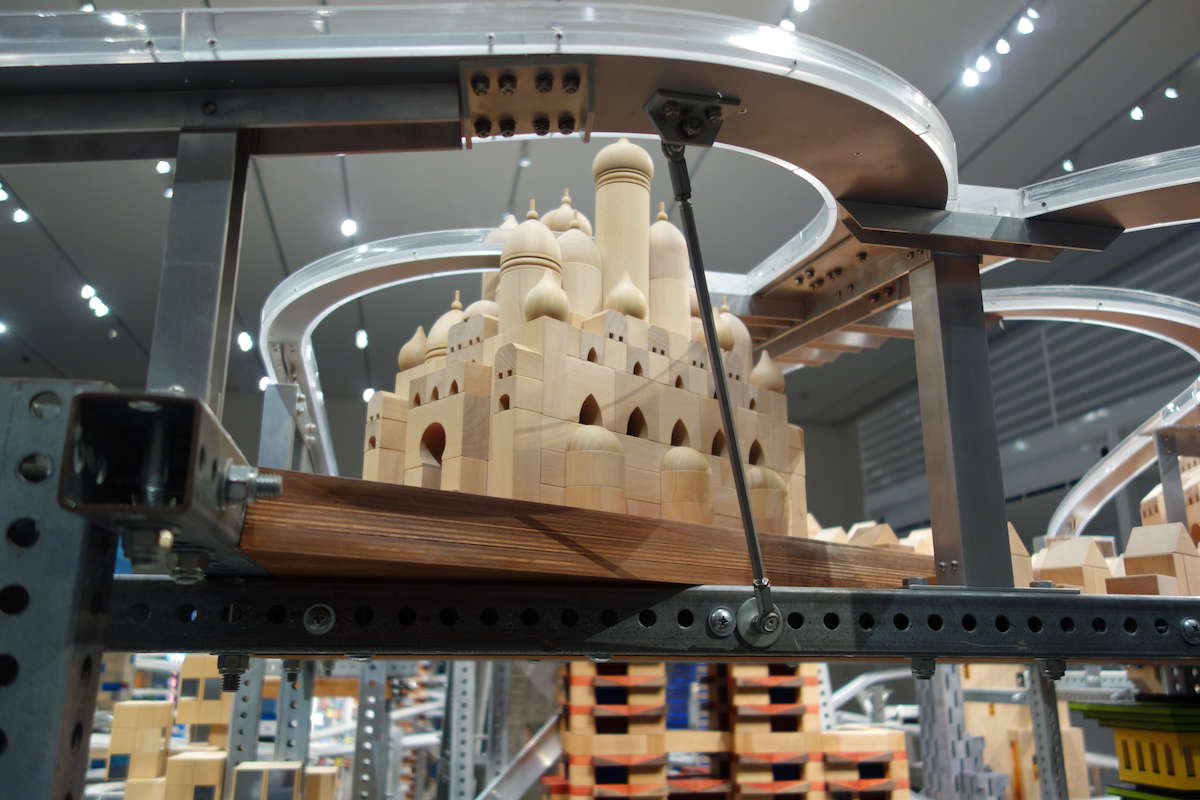

The cars, trains, and trolleys weave through a maze of buildings of varying shapes and sizes. More than 200 buildings made of HABA blocks, Lego blocks, Lincoln Logs, glass tile, stone, and acrylic densely cover the landscape.2 About 80 percent of the buildings are fixed in place, and the remaining 20 percent are partially or completely removable for disassembly/assembly of the sculpture. In general, the smaller buildings are secured with adhesive while the larger structures are bolted in place. All building components that are taller than the conveyor belt are also removable, to allow the sculpture to be packed in a cargo container. While a number of buildings are reminiscent of famous architecture, such as the Eiffel Tower, the Taj Mahal (fig. 3.5), and the Empire State Building, it was never the artist’s intent to present replicas of these structures (Citation: Schader 2012 [Schader, Susan. 2012. “‘It exists.’ Artist Chris Burden on Metropolis II.” Words & Images (blog). November. http://sschader.blogspot.com/2012/11/it-exists-artist-chris-burden-on.html.]).

It should be noted that the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, owns an earlier version of this kinetic sculpture, Metropolis I (2004). It is one-third the size of Metropolis II, with four trains and eighty cars (modified Hot Wheels). Unlike Metropolis II, this version requires two operators and is currently not on view.

Operation

LACMA is the first and, thus far, only venue that has exhibited Metropolis II, and the museum had essentially no data or information to assist us in determining the work’s longevity, the key component of which is its operation. To maximize viewership while minimizing wear and tear on the sculpture, the museum ultimately decided to operate Metropolis II on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays (the busiest days), as well as for holidays and special events. On the regularly scheduled days, the sculpture is operated four times: starting thirty minutes after the museum opens, the sculpture is run every other hour, for an hour. This allows the operator to rest (it is extremely cramped and noisy inside the sculpture), retrieve any cars that jumped the track, answer patrons’ questions, and make notes on the sculpture’s performance. Operating Metropolis II on a schedule was also in keeping with the artist’s desire not to run the sculpture continuously: Burden liked the juxtaposition of chaos and quiet, which mimicked the stop-and-go of life in a major city. Also, the frenetic pace of the cars can be exhausting to the viewer, for even a short time. For this reason, the artist designed a balcony in the gallery for viewers so they could step back from the noise and excitement and observe the sculpture as a whole from a distance.

The operators monitor the movement of the trains and make sure the cars do not jam at any brush over the roadway or at the bottom of the conveyor ramps. Operators share notes on successive days to communicate potential problems with tracks or conveyor belts that require monitoring or repair (fig. 3.6).

The sculpture has a number of built-in safety features, including overload switches (circuit breakers) for each conveyor motor, one photo-eye sensor for each conveyor belt, and one photo-eye sensor for each lower conveyor sprocket. There is also an emergency button that shuts down the entire system.

Care and Maintenance

Proper maintenance of Metropolis II proved critical to its overall operation and function. The entire sculpture is vacuumed once a week to remove dust and debris that has accumulated from the gallery. The sculpture is also inspected frequently to assess wear and identify any issues that may cause a problem in the future.

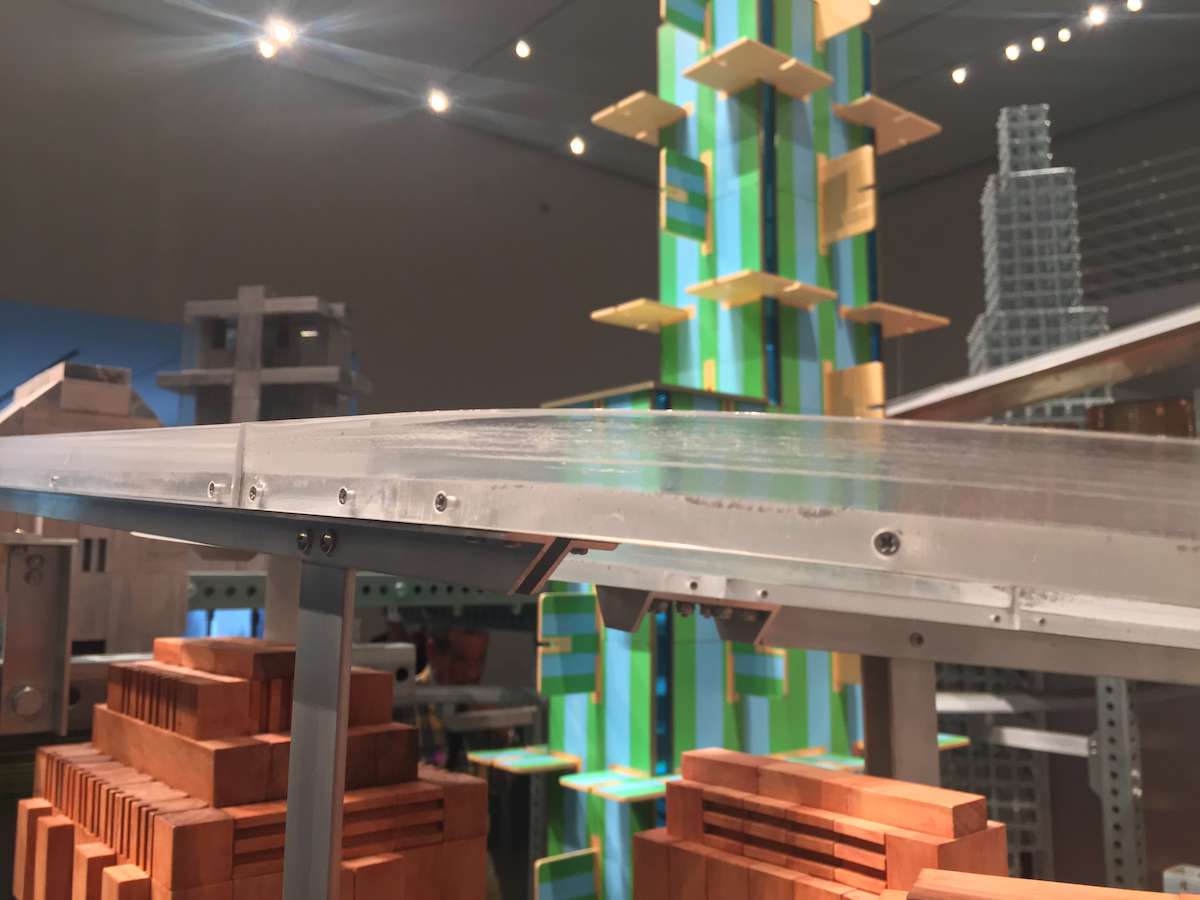

In addition to vacuuming, the plastic car tracks are fastidiously dusted by hand with a super-soft microfiber polishing cloth. As they speed around the track, the cars degrade the plastic, creating grooves in the track and generating a considerable amount of fine white powder. This wear is most pronounced along bends in the track where the cars tend to scrape against and scratch the vertical plastic retaining wall (fig. 3.7). The wear is readily apparent, yet it does not yet seem to have affected the cars’ performance so far. As a preventive measure we have explored how best to undertake the replacement of portions of the track showing the most wear. We have carefully measured and traced individual pieces of track, creating highly detailed templates and computer renderings. We now have the ability to cut sheet material using CNC (computerized numerical control) to the exact size and shape of any specific curve for future replacement.

Though the cars were designed to be robust, they take quite a beating racing down the 19.8m of roadway over and over, approximately 650 hours a year. The cars’ plastic wheels, which are press-fit onto a metal axle, fail most frequently (fig. 3.8). The hole in the wheel eventually bores out from the repetitive rotation, and the wheel itself slides off. There are no spare parts for these custom cars, so damaged parts are replaced by exchanging good parts from other used cars. When repair is no longer possible, the cars are retired to storage and a new car is used. Anticipating that the cars would wear out, the artist gave the collector 12,000 spare cars. Based on the current rate of wear and tear, we estimate that there are just enough spare cars to keep the sculpture operational throughout the loan period.

Like the tracks and cars, the trains require constant cleaning and repair. As dust collects on their wheels, the transfer of electricity from the track to their motor is compromised and causes them to sputter, stall, and/or derail. All dust and debris must be meticulously removed from the train wheel assemblies and gears every week. In addition, each train track must be carefully degreased and cleaned by hand. The motor components wear out with almost constant use. Most commonly, their plastic drive shafts are worn smooth, preventing the train from running at all. Unfortunately, the train sets are not easily replaced, given the artist’s preference for some older models that are no longer commercially available. Over the years, we have resorted to rebuilding the trains and making our own replacement parts. We are experimenting with more durable materials, such as replacing the plastic drive shafts with brass, which greatly increases the operating life of the trains. Even though they have been repaired multiple times, some of the trains have logged more than 2,000 hours of operation—well beyond the average lifetime of a model train.

The trolleys presented a unique problem, which could be traced back to the original fabrication of the sculpture. The sculpture had never been operated for more than 100 hours prior to its installation at LACMA, and it was impossible to predict how the different components of the trolley system would hold up to constant use. We discovered that the trolley circuit boards are not compatible for long-term use with the original controllers/transformer. With permission from the artist’s studio, we replaced some of the controllers with a more robust version.

Typically, the architecture requires little maintenance other than minor repair of loose or fallen building elements, which occurs periodically in response to vibration from the cars. The detachment of individual building blocks is largely due to adhesive failure. On one occasion, a patron fell into the sculpture and broke an acrylic building rooftop. Surprisingly, the damage was isolated to one piece of the roof component, and the patron was not injured. The Nicholas Berggruen Foundation approved immediate repair/replacement, and we were able to complete the work without having to close the sculpture to the public. Using the broken piece as a template, we purchased identical acrylic sheet material from the same vendor that the artist had used, cut into shape, and reassembled with the original detail elements and trimming.

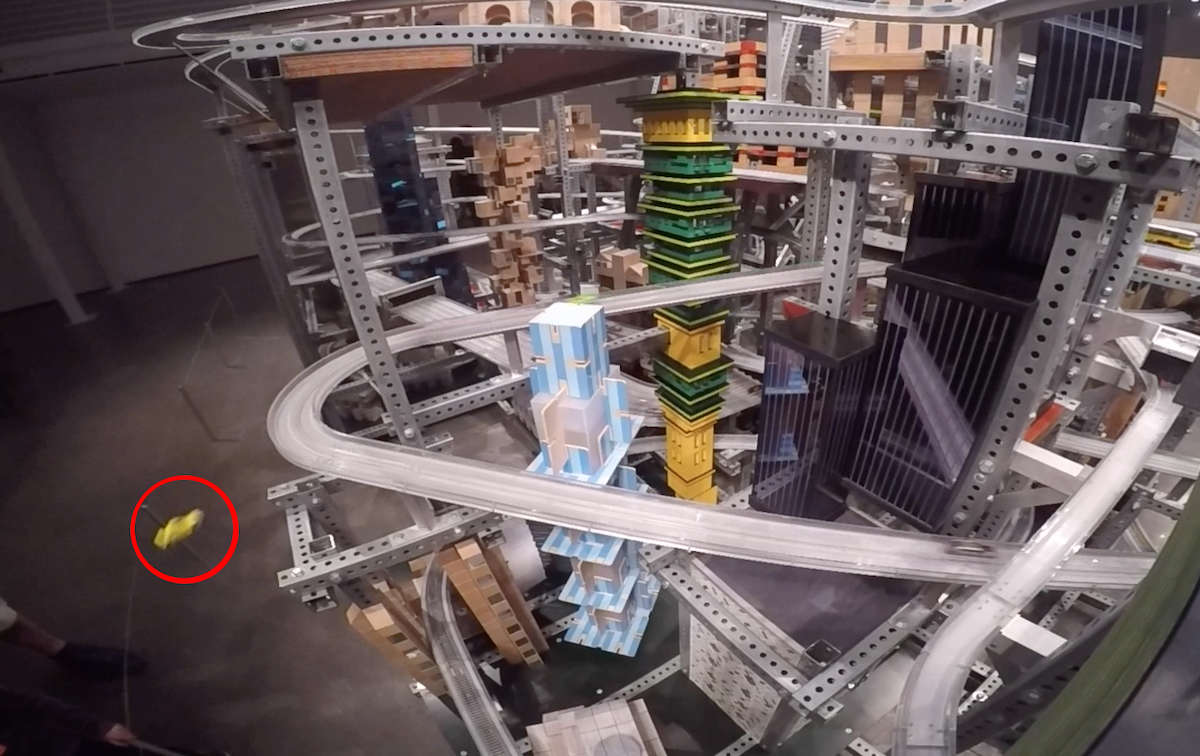

The base layer of the sculpture is composed of colored resin-coated plywood (phenolic). These plywood pieces, anchored within the metal Unistrut grid, fill in about 85 percent of the surface area of the artwork parallel to the gallery floor. As cars fly off the track, they sometimes hit this plywood or a building, leaving a visible dent. In an effort to reduce the number of dents to the base of the sculpture, we installed a GoPro camera3 to film the cars in areas where they frequently jump the track (fig. 3.9). This footage enabled the operator to identify the exact location where cars were coming off the track and which of the four car types fell off most frequently. With this information, we were able to make strategic brush adjustments to slow the cars, keep them on the track, and reduce damage to the plywood and/or buildings.

The motors that drive the conveyor system also require periodic maintenance. Intentionally installed upside down for aesthetic reasons, the oil seals are destined to fail. Because the seals were not designed to handle upside-down pressure, oil has leaked out of the gearboxes and contaminated the rest of the motor. As a precautionary measure, we are gradually replacing the original motors with oil-less motors of the same kind. In addition, as problems arose, we replaced various sensors and overload switches (motor circuit breakers) with more robust industrial versions to improve performance.

Documentation

Because Metropolis II is on loan to LACMA, it is necessary to document the condition of the sculpture over time and account for damaged cars, trains, and trolleys; however, this has also proved critical to assessing the long-term operation and maintenance costs of the artwork. Metropolis II operates almost 650 hours per year, with an average of 554 run hours before a car is retired. Each car is individually numbered, and the oldest car to date has run for more than 1,234 hours. LACMA has retired a total of 5,143 cars since the sculpture was installed in January 2012: 1,758 (in 2012), 1,090 (in 2013), 961 (in 2014), and 1,334 (in 2015). Remarkably, not a single scheduled run of Metropolis II has been missed, although the sculpture has at times been operated without several trains or trolleys. The artist approved operation of the sculpture under these conditions as long as all the cars were functional.

Conclusions

Kinetic sculptures present a range of issues and challenges, some of which are unique to the artwork. Their installation and exhibition is both costly and timeconsuming, and many museums, ill prepared to meet these challenges, frequently underestimate the resources that must be devoted to ensure their proper function and operation. Preventive maintenance is key, though it is important to have a clear understanding of how the sculpture functions, the artist’s intent, and what changes the artist will allow and support as technology changes. The exhibition of Metropolis II has proven successful primarily because LACMA was willing to take a more multidisciplinary approach to its care and preservation, embraced the assistance of the artist’s studio and staff, and allowed professional fabricators and artists to play a large role, under the guidance and direction of the museum’s conservation staff.

Notes

- HO refers to the scale system commonly used in North America for model railroads. ↩

- HABA blocks are a construction toy consisting of small wooden building blocks. Legos are construction toy consisting of small plastic bricks. Lincoln Logs are a construction toy consisting of notched, miniature wooden logs. ↩

- GoPro is an HD-quality video recording camera. ↩

Bibliography

- Schader 2012

- Schader, Susan. 2012. “‘It exists.’ Artist Chris Burden on Metropolis II.” Words & Images (blog). November. http://sschader.blogspot.com/2012/11/it-exists-artist-chris-burden-on.html.