10. Polykleitos and His Followers at Work: How the Doryphoros Was Used

- Kyoko Sengoku-Haga, Tohoku University, Honshu, Japan

- Sae Buseki, Tohoku University, Honshu, Japan

- Min Lu, Tencent Technology Co. Ltd., Shenzhen

- Shintaro Ono, The University of Tokyo

- Takeshi Oishi, The University of Tokyo

- Takeshi Masuda, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Japan

- Katsushi Ikeuchi, Microsoft Research Asia, Beijing

Abstract

Introduction

For more than a century, arguments have been made both for and against the identification of the Doryphoros with the “Canon” of Polykleitos without a definitive conclusion being reached. Although the most important information is Pliny’s famous phrase, it also is the cause of controversy. He writes: “Polyclitus … et doryphorum viriliter puerum fecit. quem canona artifices vocant, liniamenta artis ex eo petentes veluti a lege quadam …” [“Polykleitos made … and a Doryphoros, a virile-looking boy. He also made a statue which artists call the ‘Canon’ and from which they derive the basic forms of their art, as if from some kind of law.”] (Naturalis historia 34.55).1

Since the connection between the two sentences is rather abrupt, Jahn suggested it be read as “doryphorum viriliter puerum fecit [et] quem canona artifices vocant,” namely, “the sculptor made the Doryphoros and this very statue was called the ‘Canon’ by artists.” It is strange that the subject of such an important and influential work is not mentioned, given that, judging from the number of Roman copies, the Doryphoros was Polykleitos’s most famous work. This reading has therefore been supported by some2 but rejected by others.3 Furthermore, even to the broadly accepted identification of the “doryphorum viriliter puerum” with the Doryphoros type (fig. 10.1), an objection has been raised recently.4

In this confused situation, we need to reflect again on the series of Roman copies, possibly attributable to the great sculptor: first, the famous (so-called, if necessary) Doryphoros, known to us through more than sixty copies; second, the Diadumenos mentioned by Pliny in the passage cited above as the most costly work of the sculptor, copies of which we have only two (and some more head copies); third, three (or four) Amazon types, each of which was created by Polykleitos, Pheidias, or Kresilas. We also have some types of statues that might originate from disciples or followers of the great master. Of course these pieces of evidence have been available for a long time, but with the help of new technology we have the possibility of obtaining from them some substantial new data.

Methodology5

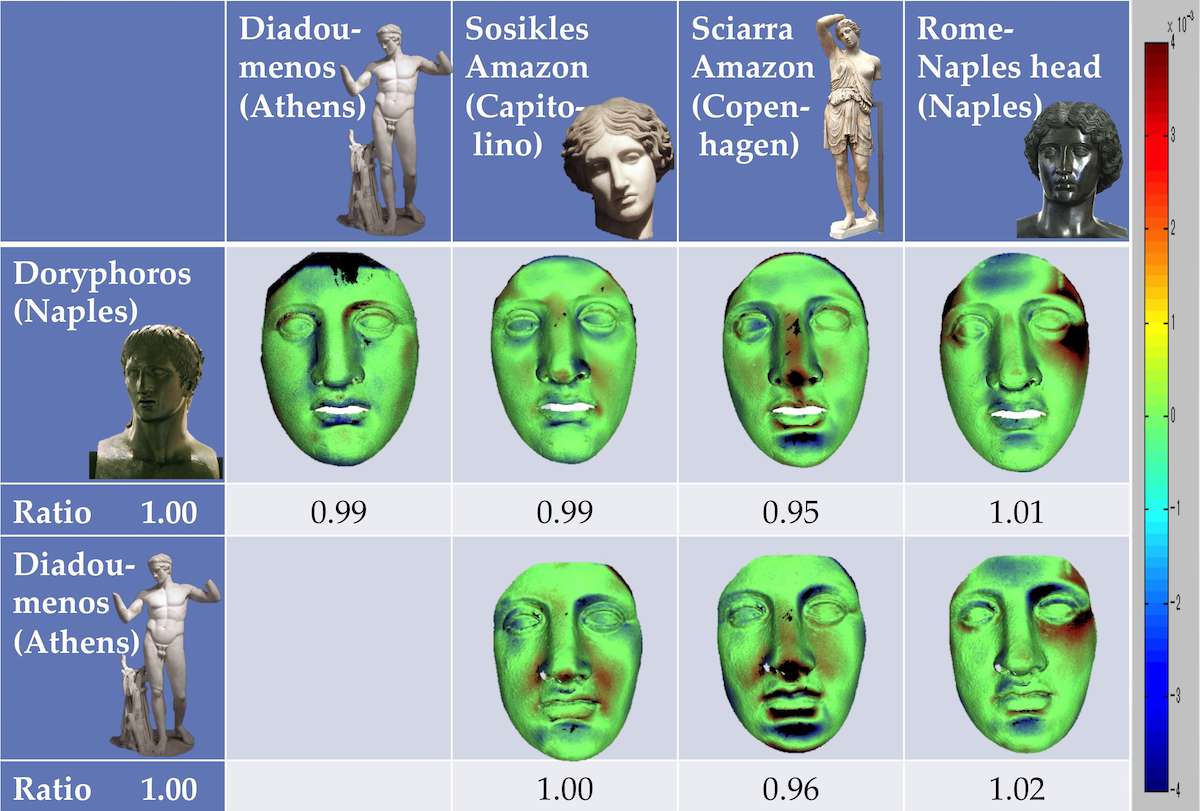

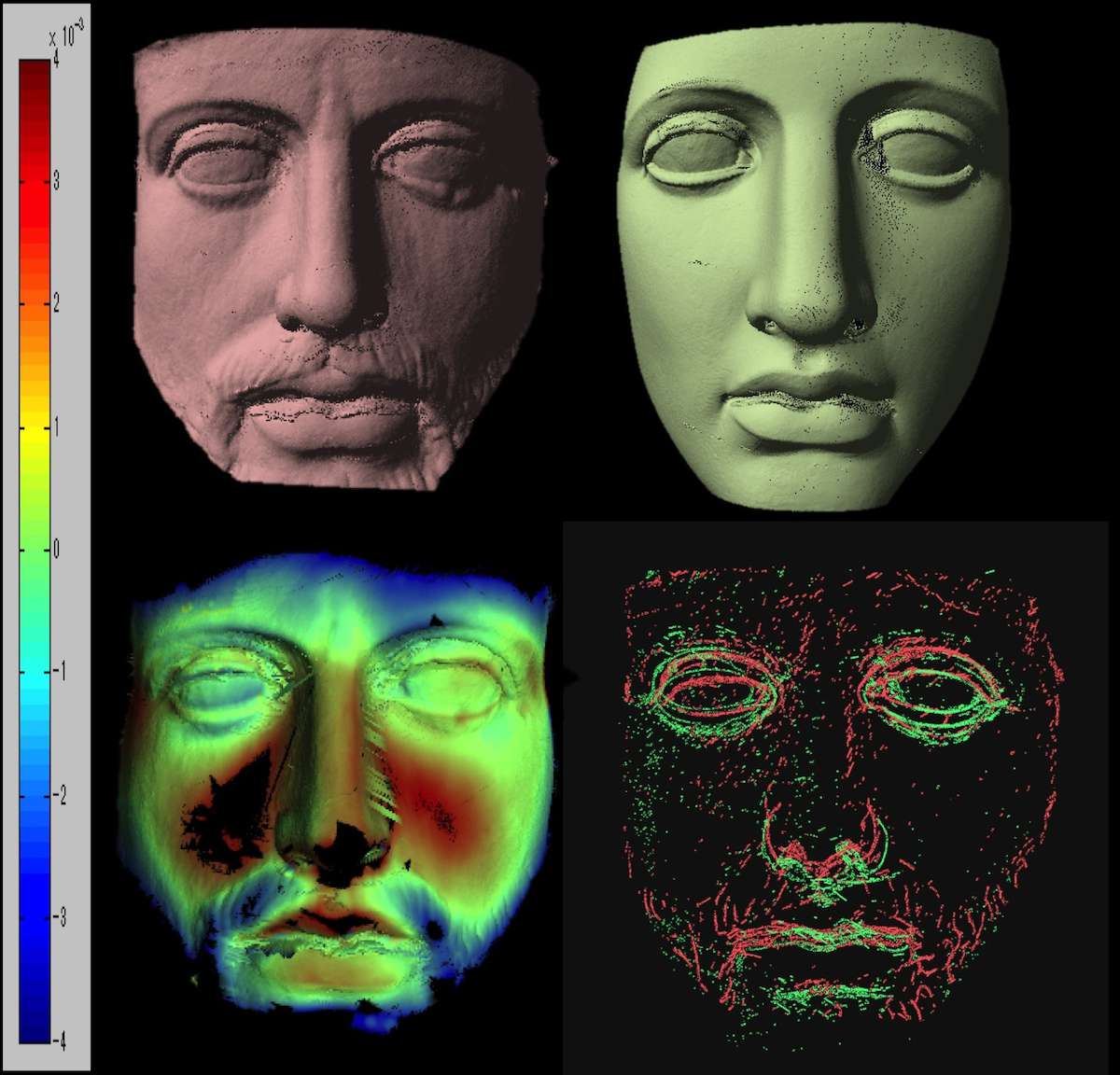

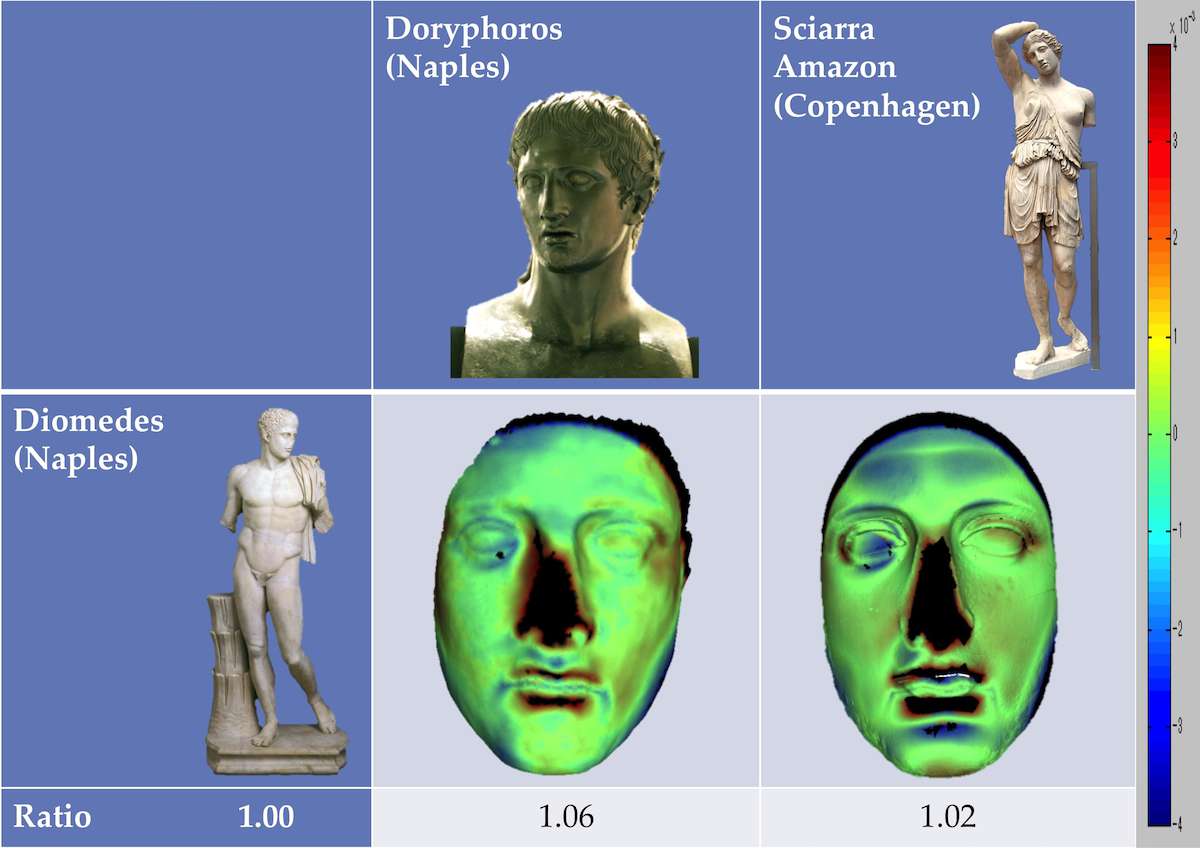

We first scanned each work (or its modern plaster casts in Munich) with a 3D laser scanner with an accuracy of ±50 μm and created a very precise 3D model. From two of the models to be compared, a pair of corresponding parts are cut out, normalized in scale if necessary, and aligned together. To clarify the distances of the gap between the two parts, two means of visualization are devised (see fig. 10.5). One is color-mapping, in which the distances of the two forms are plotted and visualized with a color-code. The threshold of the color-mapping is to be defined: in most cases, 4 millimeters (⅛ in.) so that we can recognize 1 millimeter differences. A perfect match (0 mm distance) is colored green; +1 mm yellow; +2 mm orange; –1 mm light blue, and so on. The distances over 4 millimeters are colored black. If the image is colored all green, it means that the shapes of two compared objects are identical. The second visualization method is valley-line drawing, which is useful for distinguishing gaps of important points and lines, such as eyes, eyelids, nose features, and mouths.

1. Reliability of Roman Copies

It is well known that many Roman sculptures are copies of famous Greek masterpieces, but at the same time it has been pointed out that even the mechanically carved “exact” copies are not exact in any real sense. The traditional method of Kopienkritik has revealed that Roman copies are variable in their forms, especially in their limbs, in some cases to a great extent. Still, it is too early to discard the reliability of those copies. In the case of bronze copies, you may easily imagine that they reproduce exactly their original forms, because they are replicated in the molding and casting processes. Marble copies too maintain their original forms, more or less, because in the first century BC sculptors began to carve marble copies mechanically, using instruments and/or compasses by means of which theoretically they managed to reproduce “exact” marble copies.6

But how “exact” are the marble copies?7 In the case of two almost complete copies of the Doryphoros—one excavated in the Palaestra of Pompeii (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, inv. 6011, see fig. 10.1) and the other conserved in Minneapolis (Institute of Fine Arts)—they don’t match at all when they are compared as a whole. But compared separately in body parts, they match better. Maybe it is because the copy-makers, when they took plaster casts of the original bronze statues, took molds part by part. It was also noticed that the detailed parts, such as heads, hands, and feet (or toes) match better. Obviously they were copied more accurately than the arms and legs.

Additionally, four copied heads of the Doryphoros—the bronze herm by Apollonios (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, inv. 4885, fig. 10.2) and the marble herm (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, inv. 6412), both found in Herculaneum, and the two statues above mentioned—were compared. It was noted that, while their forms are copied quite accurately, they differ among each other in scale. The head of the statue from Pompeii is bigger than the other two marble copies by 3%; this difference may be because the back of its head is not finished and therefore the scales were not calculated correctly. The bronze head, by contrast, is about 2% smaller than the other two; this difference is probably attributable to the casting process: the size of a bronze copy always becomes smaller, since clay shrinks when it dries and bronze shrinks when it cools.

With the 3D shape comparison method, it has been proven that regarding detailed parts of statues, such as heads, feet, and hands, the “exact” copies are in fact incredibly precise and their deviations are in most cases within a few millimeters.

2. The Doryphoros Reused in Polykleitos’s Own Works

Having checked the reliability of “exact” copy heads, we should go back to the fifth century BC to discuss the originals of Polykleitos: the Doryphoros, the Diadumenos, and one of the three (or four) Amazon types.8

The first two male statues are variously dated,9 but scholars agree at least on one point: the Doryphoros was created at least a decade earlier than the Diadumenos, because the latter has softer facial features, more natural wavy hair, and a more melancholic overall expression. However, the 3D comparison reveals that the face of the Diadumenos from Delos now in Athens (National Archaeological Museum, inv. 1826) and that of the bronze Doryphoros herm from Herculaneum now in Naples have surprisingly close shapes, while the former is 1% smaller than the latter (fig. 10.3). It is true that the areas between the brows and the eyelids, the nose sides, and the lip contours indicate gaps of more or less 1 millimeter. Actually, the Delian Diadumenos has the swelled upper eyelids, the slightly closed eyes, the slim nose line, and its lip contour is less marked; these differences cause the different expressions of the two heads. Some of them may be due to the Late Hellenistic sculptor who copied the Diadumenos statue around 100 BC on Delos, but that should not be the only factor causing the difference. As Pliny said, the two original statues were actually different in style and the Diadumenos was “softer” than the Doryphoros. There are small gaps to be sure, but the overall coincidence of the shapes of the facial features is more noteworthy: the position and shape of eyes, noses, and the upper lips are almost the same. If Polykleitos had modeled the two heads independently, this closeness would not have occurred. We may safely suppose that he reused the model of the Doryphoros to create the Diadumenos, using the indirect lost-wax casting method. Thus, he kept a clay model of the Doryphoros in his workshop. Later, to create a new work, he took molds of this model, at least of the face, and then added some small changes and remodeled the hair to create a new clay model, the Diadumenos, which he fired to make durable.

Polykleitos also created an Amazon statue in competition (or, more probably, in collaboration) with other contemporary sculptors to dedicate it in the sanctuary of Artemis at Ephesos (Pliny Naturalis historia 34.53). Three or four Classical Amazon types are known, but scholars have not arrived at an agreement on the type to be attributed to Polykleitos.10

We tried 3D shape comparison for three Amazon heads (the Sosikles-type head in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, inv. 1091; the Sciarra type in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek in Copenhagen, inv. 1658; and the bronze head of Rome–Naples type, often attributed to the Mattei type, in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, inv. 4889) with the works of Polykleitos: the bronze herm of the Doryphoros from Herculaneum in Naples and the Diadumenos from Delos in Athens.11 The results were quite clear (see fig. 10.3). While the comparisons with the Sciarra type and the Rome–Naples type show some black areas, the comparison with the Sosikles type has almost no black area. They are as close as the pair of the Doryphoros and the Diadumenos and, between the two statues, the Sosikles type is closer to the Doryphoros than the Diadumenos. We can conclude that the gap between the heads of the Doryphoros and the Sosikles Amazon are within the range of works from one model. This is quite strong evidence to affirm that the Sosikles type was created by Polykleitos, reusing the model of his Doryphoros.

3. Kresilas

Since most scholars agree with the attribution of the Mattei type (either with or without the Rome–Naples head type) to Pheidias,12 the remaining one, the Sciarra type, is to be attributed to Kresilas. He was a native of Kydonia in Crete but was active mainly in Athens.13 Probably around 430 BC, he collaborated with Polykleitos on the group of Amazons at Ephesos and inevitably should have been influenced by the greater sculptor; his Amazon shows the same head inclination and a hairstyle similar to (but less naturalistic than) that of Polykleitos. However, these similarities are superficial and do not originate from the reuse of Polykleitos’s model, as has been shown by the 3D shape comparisons (see fig. 10.3). This is understandable because Kresilas was an independent sculptor and did not belong to Polykleitos’s workshop.

Although he was less renowned than Polykleitos, Kresilas made a highly regarded portrait of Pericles (Pliny Naturalis historia 34.74). Pausanias (1.28.2) saw Pericles’s portrait near the Propylaia of the Acropolis in Athens without mentioning the sculptor’s name. Excavations on the Athenian Acropolis have unearthed a statue base on which the name of Kresilas was inscribed as a sculptor, but without the name of Pericles.14 However, a portrait type of Pericles is attested in several Roman marble copies, two of which are inscribed with Pericles’s name.15 All these pieces of evidence—Pliny, Pausanias, the Acropolis base, and marble copies—seem to refer to a single work: Kresilas’s portrait of Pericles erected on the Acropolis. Still, we are not absolutely certain about its identification.

At first glance, the Sciarra Amazon and the Pericles portrait don’t look alike at all. While the Sciarra Amazon has an idealized female head, the Pericles is male with a beard, a mustache, and sagging cheeks. Besides, the nose of the Pericles herm in the British Museum is restored. Keeping all these obvious differences in mind, we dared to compare the Sciarra head in Copenhagen and Pericles head in the British Museum (fig. 10.4).16 In the image of the color-mapping visualization (fig. 10.5, left below), wide areas of the above-mentioned parts (the nose, the cheeks, and the mustache area) are colored in blue, red, or black; that is, their 3D shapes differ by more than 4 millimeters. However, using the valley-line visualization, we ascertained that the eye forms match perfectly and that the positions of nose and mouth are the same (fig. 10.5, right below), indicating that the Sciarra Amazon has the same facial features as the Pericles portrait. Although the results were not firm enough to prove the sculptor’s reuse of his own model, they support at least the attribution of both works to the same sculptor, Kresilas.

4. The Doryphoros Reused in “Diomedes”

In addition to the statuary types whose originals have been attributed to Polykleitos himself, there are several Classical statue types that more or less recall his style. Scholars have debated whether they are works by one of his disciples or simply influenced by his works, judging from the fidelity to the great master’s principles of body structure.17

The so-called Diomedes, known from one replica from Cuma (Naples, National Archaeological Museum, inv. 144978, figs. 10.6–7) and another in Munich (Glyptothek, inv. 304), is one of such statues.18 Its pose and the modeling of the torso are very close to those of the Doryphoros, except for the left foot positioned slightly farther to the left. The biggest change is the direction of the head, which turns strongly to the opposite side to gaze at something. Some scholars attribute it to the circle of Polykleitos, but others prefer to attribute it to Kresilas based on its similarity with Pericles’s head and the leg position identical with the Sciarra Amazon.19

To determine its relationship to Polykleitos or to Kresilas, we compared the face of Diomedes in Naples to the bronze Doryphoros herm in Naples and the Sciarra Amazon in Copenhagen, using 3D imaging. The results show a clear discrepancy with the Sciarra Amazon and a similarity to the Doryphoros (fig. 10.8). In both cases, the nose parts are black because that of Diomedes is broken. While the eyes and the mouth of the Sciarra Amazon are out of position, the eyes of the Doryphoros are in exactly the same place. It is true that Diomedes’s mouth is smaller, in a slightly higher position, and its cheeks are slimmer than those of the Doryphoros; this can be explained as a modification of the mouth shape and an addition of the short beard on Diomedes’s cheeks. The rest of the image is colored green, indicating that the gap between the surfaces is almost zero. As a whole the shape of Diomedes’s face is quite similar to that of the Doryphoros, which suggests that the sculptor of Diomedes did not merely imitate the pose and the style of the Doryphoros, but he used the Doryphoros as his model. He was not Kresilas but rather a sculptor to whom the model of the Doryphoros was available.

Who could use the Doryphoros model? In the later period, copy-makers took plaster casts from bronze statues displayed in public spaces,20 but in the Classical period such an operation is not likely. Most probably, the “Diomedes sculptor” was one of Polykleitos’s disciples who worked in his master’s workshop. It is true that the Diomedes sculptor, in addition to making some modifications to his master’s model, tried another solution for the balance and proportion of the male body. As is often the case of an excellent disciple, he deviated from his master.

Conclusion

We have asserted that the model of the Doryphoros was reused not only by Polykleitos himself but also by another sculptor, most probably one of his disciples. Interestingly, so far as we have discerned, the later works are always smaller in scale than the Doryphoros. Taking into account that the face of the bronze Doryphoros is around 2% smaller than those of the other two marble copies, we can calculate that the Amazon Sosikles and the Diadumenos are around 3% smaller than the marble Doryphoros, and the Diomedes statue, around 7% smaller than it.

This scaling-down may be explained as shrinkage of the clay model. Theoretically, if Polykleitos kept a clay model of the Doryphoros in his workshop, to create another work he would have taken a mold from the Doryphoros model and, modifying some details, created a new clay model. Before casting in bronze, the sculptor should have dried and baked the new model to increase its durability, thus inevitably the model’s size was reduced. In the case of his disciple, if he kept a new Doryphoros model in his own workshop, this reproduction should have always been smaller than the original Doryphoros model.

Adopting the indirect lost-wax casting technique, probably from the beginning, Polykleitos intended the model of the Doryphoros to be reused. Remembering that the Doryphoros is almost 2 meters (158 in.) tall, larger than normal statues of athletes and heroes, a question comes to mind: did Polykleitos create the Doryphoros larger expecting to scale it down when reusing it for other works? Being a skilled sculptor, Polykleitos would have anticipated this shrinkage. If that is the case, we might call the Doryphoros the “Canon,” created for the purpose of being “cited” in other works by Polykleitos and other artists. Then Pliny’s phrase, cited earlier, should be read in the way proposed by Jahn: “Polykleitos made a Doryphoros, which artists call the Canon and from which they derive the basic forms of their art.”

Since we have proved the reuse of the Doryphoros’s face model and the shrinkage in size of the faces in only a few samples, our conclusion is still preliminary. Nevertheless, we are at least certain of the great potential of the method of the 3D shape comparison in the study of ancient sculpture.

Acknowledgments

For generous permission and kind assistance during the scanning, I am particularly grateful to Dr. Ingeborg Kader, museum management and chief keeper of the Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke München; Dr. Teresa Elena Cinquantaquattro, then superintendent of the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei; and Dr. Valeria Sampaolo, then director of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. I am also deeply grateful to my colleague Todd Enslen for revising my manuscript. This work is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23320040, 16K02262, and Microsoft Research CORE 12 Project.

Notes

- Translation by Pollitt 1990, 75. ↩

- Jahn 1851, 315–16; Furtwängler 1893, 422; Hafner 1997, 10–18 with n. 10. ↩

- Pollitt 1990 (see n. 1 above); Stewart 1990, 264, T62; DNO 1234. ↩

- Franciosi 2003. ↩

- For technical details, see Zhang et al. 2013, 58–59. (The preliminary results regarding Polykleitos’s Amazon, on p. 60 of that paper, are to be corrected. See Sengoku-Haga et al. 2015.) ↩

- Pfanner 1989. ↩

- In detail, see Sengoku-Haga et al. 2015, 205–7. The 3D data of the Minneapolis Doryphoros were obtained through the scan of a plaster cast conserved in the Museum of Classical Statues in Munich. ↩

- In detail, see Sengoku-Haga et al. 2015, 207–14. ↩

- Stewart 1990 (Doryphoros ca. 440 BC, Diadumenos ca. 430 BC); Borbein 1996 (Doryphoros 450–440 BC, Diadumenos ca. 420 BC). ↩

- Bol 1998 (with a catalogue of replicas). ↩

- For details, see Sengoku-Haga et al. 2015, 210–13. The 3D data of the Sciarra type Amazon in Copenhagen were scanned from a plaster cast in the Museum of Classical Statues in Munich. ↩

- Except for Weber (1976; 2008), who attributed the Mattei type to Kresilas. As for the Rome–Naples type, attribution to Pheidias is supported by von Steuben (Helbig4 no. 2261). In contrast, Bol (1998, 187, no. I.26) put this head type into the variant of the Sciarra type, and Mattusch (2005, 278) calls it a “Polykleitan” head. Weber (1976), Raeder (1983, 77–78, no. I.64), and Boardman (1985, 217), preferred the Petworth head as belonging to the Mattei type. ↩

- As for Kresilas, see Vierneisel-Schlörb 1979, 79–93; Rolley 1999, 149–52; Vollkommer 2001, s.v. Kresilas (M. Weber); DNO II, 337–50. ↩

- IG I2 528; Raubitschek 1949, no. 131. ↩

- See Richter and Smith 1984, 173–75. ↩

- We scanned plaster casts in Munich. ↩

- For example, Linfert 1990; Rolley 1999, 42–51. ↩

- Admitting the strong influence of the Doryphoros, many scholars denied the relationship of the Diomedes sculptor to Polykleitos’ workshop, based on its departure from the Canon in its structure. Stewart 1990, 168; Stewart 1995, 251–53; Linfert 1990, 289. See also n. 19 below. ↩

- Attribution to Kresilas: Furtwängler 1893, 311–25; Vierneisel-Schlörb 1979, 79–93; Weber 2008, 11. ↩

- Lucian Iuppiter tragoedos 32–33. ↩

Bibliography

- Boardman 1985

- Boardman, J. 1985. Greek Sculpture: The Classical Period: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Bol 1998

- Bol, R. 1998. Amazones Volneratae: Untersuchungen zu den Ephesischen Amazonenstatuen. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Borbein 1996

- Borbein, A. H. 1996. “Polykleitos.” In Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture, ed. O. Palagia and J. J. Pollitt, 66–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DNO

- Der Neue Overbeck (DNO): Die antiken Schriftquellen zu den bildenden Künsten der Griechen, ed. S. Kansteiner et al. 5 vols. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Franciosi 2003

- Franciosi, V. 2003. Il “Doriforo” di Policleto. Napoli: Jovene Editore.

- Furtwängler 1893

- Furtwängler, A. 1893. Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik. Leipzig and Berlin: Giesecke & Devrient.

- Hafner 1997

- Hafner, G. 1997. Polyklet, Doryphoros. Revision eines Kunsturteils. Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch.

- Jahn 1851

- Jahn, O. 1851. “Zu Plinius.” RhM 9: 315–20.

- Linfert 1990

- Linfert, A. 1990. “Die Schule des Polyklet.” In Polyklet: Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik, ed. H. Beck, P. C. Bol, and M. Bückling, 240–97. Frankfurt: Philipp von Zabern.

- Mattusch 2005

- Mattusch, C. C. 2005. The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculpture Collection. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Pfanner 1989

- Pfanner, M. 1989. “Über das Herstellen von Portäts.” JdI 104: 157–257.

- Pollitt 1990

- Pollitt, J. J. 1990. The Art of Ancient Greece: Sources and Documents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Raeder 1983

- Raeder, J. 1983. Die statuarische Ausstattung der Villa Hadriana bei Tivoli. Frankfurt am Main and Bern: Peter Lang.

- Raubitschek 1949

- Raubitschek, A. E. 1949. Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis: A Catalogue of the Inscriptions of the Sixth and Fifth Centuries B.C. Cambridge, MA: Archaeological Institute of America.

- Richter and Smith 1984

- Richter, G. M. A., and R. R. R. Smith. 1984. The Portrait of the Greeks. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Rolley 1999

- Rolley, C. 1999. La sculpture grecque. Vol. 2: La période classique. Paris: Picard.

- Sengoku-Haga et al. 2015

- Sengoku-Haga, K., Y. Zhang, M. Lu, S. Ono, T. Oishi, T. Masuda, and K. Ikeuchi. 2015. “Polykleitos’ Works ‘from One Model’: New Evidence Obtained from 3D Digital Shape Comparisons.” In New Approaches to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, ed. A. Patay-Horváth, 201–22. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Stewart 1990

- Stewart, A. 1990. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. 2 vols. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Stewart 1995

- Stewart, A. 1995. “Notes on the Reception of the Polykleitan Style: Diomedes to Alexander.” In Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition, ed. Warren G. Moon, 246–61. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Vierneisel-Schlörb 1979

- Vierneisel-Schlörb, B. 1979. Klassische Skulpturen des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Glyptothek München, Katalog der Skulpturen 2. Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Vollkommer 2001

- Vollkommer, R., ed. 2001. Künstlerlexikon der Antike, 2 vols. Munich and Leipzig: K. G. Saur.

- Weber 1976

- Weber, M. 1976. “Die Amazonen von Ephesos.” JdI 91: 28–96.

- Weber 2008

- Weber, M. 2008. “Neues zu den Amazonen von Ephesos.” Thetis 15: 45–56.

- Zhang et al. 2013

- Zhang, Y., M. Lu, B. Zheng, T. Masuda, S. Ono, T. Oishi, K. Sengoku-Haga, and K. Ikeuchi. 2013. “Classical Sculpture Analysis via Shape Comparison.” In 2013 International Conference on Culture and Computing, 57–61. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6680331/.