9. More Than Holes! An Unconventional Perspective of the “Greek Revolution” in Bronze Statuary

- Gianfranco Adornato, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa

Abstract

1. Defining the Severe-Style Period

The artistic revolution in Greek sculpture is generally associated with one fundamental historical event, the Persian Wars; with two of the most important sculptors of the late sixth–early fifth century BC, Kritios and Nesiotes; and with a sculptural group: the Tyrannicides. The chronological span between the end of the Persian Wars—marked by the destruction of the monuments on the Athenian Acropolis (480/479 BC)—and the beginning of the construction of the Parthenon (448/447 BC) is commonly labeled as the “Severe style period” in archaeological literature.1 In this paper I discuss the notion of the artistic revolution in Greek art from an unconventional and entirely neglected perspective: the dowel holes on statue bases. I investigate the archaeological evidence in order to single out and highlight technical improvements in Greek sculpture, which in turn had aesthetic implications.2

As far as I know, Gustav Kramer was the first scholar to introduce the term “Severe style.” In his 1837 contribution on Greek vases, he identified three main phases: the Old style (Alter Styl) up to Olympiad 80 (460 BC); the Severe style (Strenger Styl) to Olympiad 90 (460–420 BC); and the third period, the Beautiful style (Schöner Styl) until Olympiad 100 (420–380 BC).3 It is evident that his classification and chronology do not coincide with the stylistic labels currently adopted in archaeological literature and handbooks.

Since the publication of Vagn Poulsen’s Der strenge Stil in 1937, the term has been used unequivocally to indicate a specific period and style: to Poulsen and those who followed, Kritios, Nesiotes, and the Tyrannicides represented the turning point and the very beginning of a new period and style.4

Ridgway concurred and catalogued the most prominent traits of the Severe style: “the official date of the Tyrannicide group by Kritios and Nesiotes, 477 BC, can therefore be considered the legal birthday of the Severe style.”5 More recently, Stewart defined this cultural and artistic phase and concluded, “the totality of the evidence from the stratigraphy, architecture, pottery, and sculpture of the Acropolis deposits supports the theory that the Severe Style began (just) after the Persian sack.”6 Stewart considers the Tyrannicides “not only the earliest dated monuments in the new style but also themselves revolutionary.”7

Which new and revolutionary stylistic and technical criteria do we find looking at the artistic production of Kritios and Nesiotes in comparison with previous sculptures? And what kind of appreciation of their works of art can we find in ancient literary sources? Furthermore, does the word “severe” correctly translate Greek and Latin adjectives?

2. Signed Bases, Dowel Holes, and Iconography

The names of the artists Kritios and Nesiotes are known from six inscriptions found on statue bases on the Acropolis, three of which are diagnostic for the purposes of this analysis.8 The dowel holes on these bases allow us to reconstruct the poses and schemes of the figures mounted on them and to evaluate their technical novelty. On the top of the pedestal dedicated by Epicharinos (fig. 9.1),9 two dowel holes are recognizable, even though it is not easy to reconstruct the pose of the figure: it stood either with the left foot advanced, to be seen in profile, or with the right foot advanced, facing the viewer. In any case, the figure was standing with both feet on the ground.

On top of the base dedicated by Hegelochos, father and son of Ekphantos (fig. 9.2), two dowel holes placed widely apart make it appear as if the base supported a large-scale bronze figure: it is possible to reconstruct Hegelochos’s dedication as an approximately life-size, striding male warrior in an attacking pose (a pose identical to that of an Athena Promachos).10

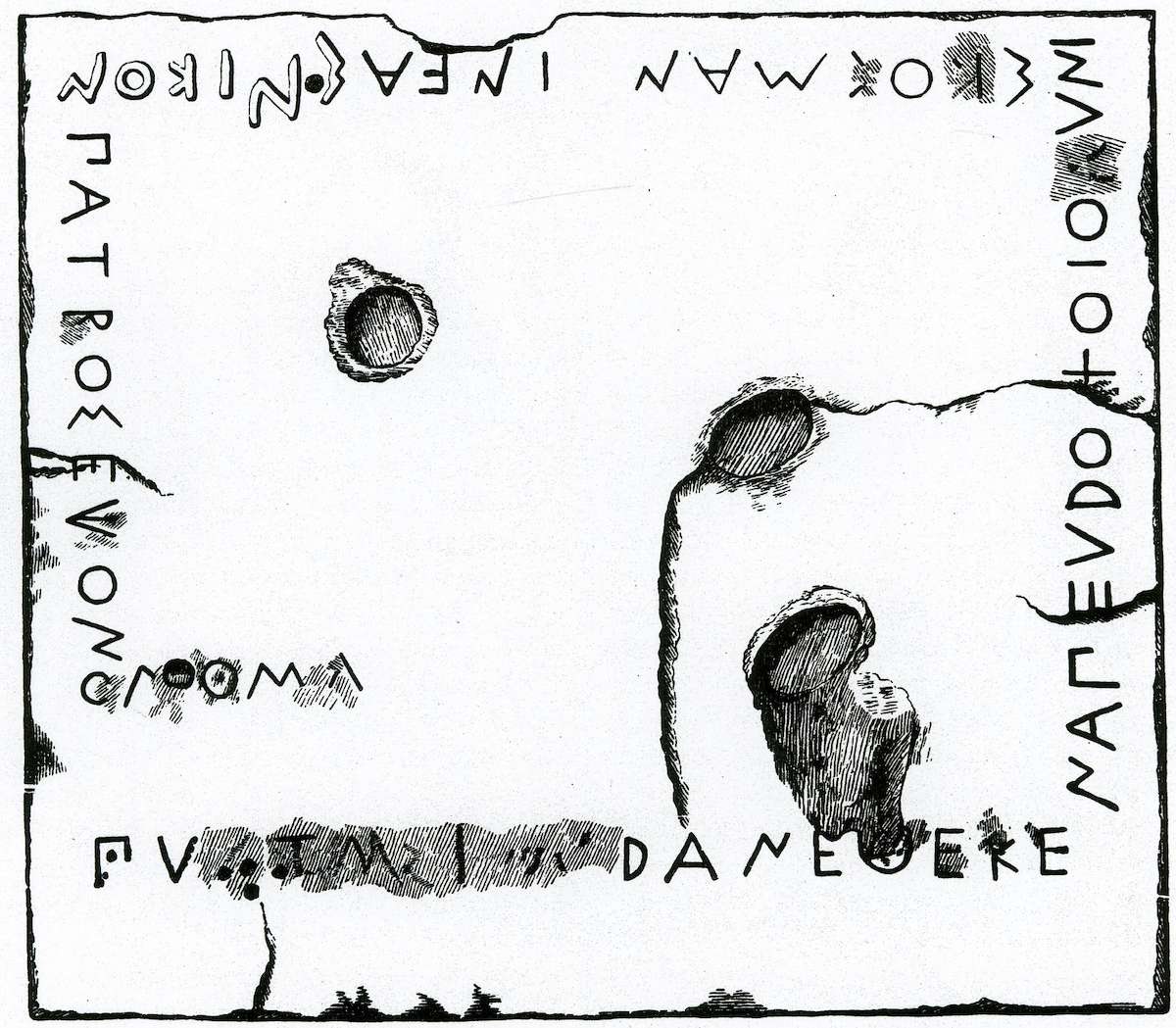

The circular base dedicated by “[ … ]as and Ophsios” (fig. 9.3) presents two long dowel holes on the surface. The shape of the base is not common and it may be that one of the unfinished column drums of the older Parthenon was reused as a pedestal. The position of the dowel holes shows that the bronze statue, a lost bronze Athena,11 stood with its feet close together; the statue was standing and not in motion.

Unfortunately, we cannot evaluate style and technique of those lost sculptures by Kritios and Nesiotes. However, thanks to the presence of the dowel holes on the bases, it is possible to pinpoint some aspects related to the typology and the iconography of the statues. On two monuments, the figure is represented standing with both feet anchored to the ground, according to poses already attested in the sixth century BC. More interesting is the case of Hegelochos’s dedication: the figure was represented with legs spread, like those of the coeval Tyrannicides.

Going back to the initial issues, were the pose and the iconography new and revolutionary in comparison with the sculpture of the (Late) Archaic period? The answer is negative, since Kritios and Nesiotes adopted and exploited typologies that were already in use in different media and at various scales in Late Archaic artistic production. Examples include the imposing Athena Promachos from the Gigantomachy pediment, the Ugento Zeus, and, in small format, a bronze hoplite statuette from Dodona.12 The tradition of this pose is documented on the Athenian Acropolis after 480 BC, as we can see on the small bronze depicting Athena, dedicated by Meleso.13 In sum, the poses and typologies used in the sculptures of Kritios and Nesiotes appear not to be innovative in comparison with previous statues.

The Tyrannicides14—representing the attack by Harmodios and Aristogeiton—are constructed employing a well-established iconography: legs spread, rear foot lifted, torso erect, arm raised, and head held frontally.15 The vehement action of the two protagonists is not reflected in their abdominal muscles—which while precisely detailed are not very natural in terms of rendering movement—or in the position of the heads, which are held straight and facing fixedly forward on muscular necks.16 We have the same impression observing coeval sculptures like the Miletus torso, the statues of athletes from Delos, or the archer from the Acropolis.17

In literary sources, statues made by Kritios and Nesiotes were not highly appreciated. In a rhetorical context, Lucian gives aesthetic evaluations of the “hardness” of the sculptures, mentioning the sculptor Hegias (also called Hegesias) in association with the more renowned figures of Kritios and Nesiotes. In chapter 9 of his Rhetorum praeceptor, the author mentions as exemplary (paradeigmata) exponents of ancient technique (palaia ergasia) Hegias and artists around Kritios and Nesiotes,18 characterizing their works as rigid (apesphigmena), robust and muscular (neurode), hard (sklera), and precisely divided into parts with lines (akribos apotetamena tais grammais).19

Although in modern historiography the two sculptors are considered to be the pioneers of the artistic revolution of the Severe style, in ancient literary sources they are classified among the “hard” (sklera, Lucian). Furthermore, in a well-known passage of the Institutio oratoria by Quintilian (12.10), Hegias’s style is described as “harder and close to Etruscan statues” (duriora et Tuscanicis proxima).

It is interesting to note how the Greek and Latin adjectives associated with the artists of this period (skleros, durus, rigidus) have been rendered in modern translations as severo,20 severe,21 sévère,22 and streng23 in an attempt to put a positive twist on an aesthetic concept that was by no means positive for the ancients. This connotation does not seem to be supported by textual analysis of these adjectives used in other contexts, where they definitely indicated rigidity, fixedness, and immobility.24 According to scholars such as Strocka and Stewart, this wording can be traced back to a formulation suggested by J. J. Winckelmann.25 Reading Winckelmann, however, I realized that he used the adjective streng not to characterize ancient artists but solely in connection with a modern artist; he contrasted the “correct and strict” style (die richtig und streng angegebenen Figuren) of Raphael with the gentler style (die rundlich und sanft gehaltenen Formen) of Correggio.

From a technical and art historical point of view, it is not until the activity of Polykleitos and his “Canon” that we have a clear testimony of interest in the movement of the body and its laws: the inflection of the anatomy, the position of the head, and the movement of the body are all precisely anatomically reflected in the individual parts. That sculptor’s distinction, as we read in Pliny, was to have created statues standing on one leg (proprium eius est uno crure ut insisterent signa excogitasse), breaking with the traditional stance of sculptures characterized by a certain sense of rigidity and immobility of the figure.26 We need only compare works attributed to Polykleitos with other coeval sculptures to visualize and understand his achievements. In his works27 we detect the surpassing of the previous anatomical schema: on the base of Kyniskos of Mantinea (fig. 9.4),28 we find a very peculiar positioning of the lower limbs, with the left foot barely resting on the ground and the right held to the rear with the heel raised. This ponderation (the tension of the figure moving from resting to moving) is found in both the Doryphoros and in the Diadumenos statues. Perhaps due to this new artistic concept and its technical solution, Quintilian reported that Polykleitos’s statues were perceived as lacking stability (deesse pondus putant) compared to those of Pheidias.29 In previous translations, pondus has been rendered as “grandeur, solemnity, majesty”30 and connected to his style and iconography of the statues. Polykleitos was thought, Quintilian continues, to have been less successful in representing the dignity of the gods (deorum auctoritas), and was further alleged to have shrunk from representing persons of mature years, having ventured on nothing more difficult than a smooth and beardless face. I would like to propose an alternative translation of pondus, namely “stability, equilibrium,” to be connected with the new pose and stance “on one leg” (uno crure), as attested in Pliny’s passage (Naturalis historia 34.56).

In order to support this hypothesis, we can look at sculptural evidence. For instance, we can compare the anatomical structure of the Kassel Apollo (believed to be a replica of the Parnopios Apollo) or the Lemnian Athena,31 as passed down through Roman copies, with the Kyniskos statue, as far as we can reconstruct it based on holes for mounting: we find a major difference in balance and stability. The impression gathered from an examination of these statues attributed to Pheidias is one of stable poses and solid bodies, while Polykleitos’s works of art are not well balanced. For this reason, Polykleitos’s statues were not appropriate for the representation of gods.

This comparison allows us to fully comprehend the importance of Polykleitos’s achievement, the final outcome of a long, slow, continuous technical process begun at the end of the sixth century BC, through small but significant formal stages.

This analysis brings me to conclude that significant changes in Greek sculpture are to be detected around that time: it is a transitional period, which seems to include the second quarter of the fifth century BC. I favor a paradigm of continuity instead of a clear-cut division of artistic periods, artists, and styles: the poses, typologies, and iconography of statues of the second quarter of the fifth century BC are inherited from the past. Furthermore, Late Archaic artists of the ancient Mediterranean worked both before and after the year 480 BC (some of them were spared by the Persians!): the case of Kritios and Nesiotes is self-evident in this regard. This experimental phase lasted several decades until the middle of the fifth century: it is with Polykleitos that we detect a significant change, a disruptive innovation in pose and scheme in comparison with the previous artistic production.

This notwithstanding, the notion of a “Severe style period” need not be expunged from handbooks, but we must be aware that we use it as a modern, conventional art historical label, somewhat misleading yet nonetheless useful. Reading ancient sources is very instructive on the perception of aesthetic evaluation and judgments of ancient art and artists and the modern reception of it in the construction of an art historical system. In epigram 62 by Poseidippos of Pella, for instance, there is no distinction between the Late Archaic and Classical periods, between Late Archaic and Classical artists. To him, what happened before Lysippos’s activity is considered as an indistinct entity.32 According to Latin literary sources,33 the art of bronze sculpture proceeds through formal steps and advancement, adopting the scale of hardness and beauty: from the most rigid statues by Late Archaic artists to the less rigid statues by Kalamis, to the beautiful ones by Myron and those more beautiful still by Polykleitos. In this frame of progress and continuity, it must be clear that to the ancients the Severe style as a chronological and stylistic category never existed.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of a wider project on a technical lexicon and art criticism in ancient sources: thanks to a National Research Fund (PRIN 2012), as Principal Investigator I am currently working on a new edition of and commentary on Pliny the Elder’s Books of Art. I am grateful to Jens Daehner for his invaluable comments on the manuscript.

Notes

- See Stewart 1990; Rolley 1994; this chronological span is also labeled as “transition period” (Richter 1951) or “Bold Style” (Harrison 1985), among others. ↩

- A thorough investigation on the development of technique is in Mattusch 2006; see also Adornato 2008. ↩

- Kramer 1837, 101. ↩

- Poulsen 1937. ↩

- Ridgway 1970, 12. Already Poulsen 1937, 116. ↩

- Stewart 2008a, 406–7. ↩

- Stewart 2008b, 608 (my italics). ↩

- Raubitschek 1949, no. 161: the fragment found between 1877 and 1886 west of the Erechtheion contains too few letters to be included in this analysis. No. 161a is not included because the fragment was found in the Agora and contains just a few letters. ↩

- IG I3, 847 = DAA 120; Keesling 2003, 170–72. ↩

- IG I3, 850 = DAA 121; Raubitschek 1949, 128; Keesling 2003, 186–90. ↩

- IG I3, 848 = DAA 160; Keesling 2000. ↩

- Athens, Acropolis Museum, inv. 631: Stewart 1990, 129; Taranto, National Archeological Museum, inv. 121327: Adornato 2010, 318–20; Berlin, Staatliche Museen, inv. Misc. 7470: Stewart 1990, 147. ↩

- Athens, Acropolis Museum, inv. X 6447: Stewart 2008a, 385, 388, 410. ↩

- Naples, National Archaeological Museum, inv. 6009 and 6010; FGrHist 239 A 54; Marm. Par. A, ll. 70–71 (IG 12.5.444, 70–71); Brunnsåker 1971; Taylor 1991. ↩

- De Cesare 2012. ↩

- This is in disagreement with Stewart (1997, 73), who writes that “its revolutionary ‘severe’ or early classic style with its emphatic, powerfully organic, yet still rigorously ordered articulation of the male body did what the archaic style’s calligraphic patterning could not do.” I argue, on the contrary, that the rendering of the joints and muscles is still bound to the formal conventions and traditions of the Late Archaic period. ↩

- Paris, Louvre, inv. Ma 2792: Bol 2005; Delos, Archaeological Museum, inv. A 4275, A 4276, A 4277: Hermary 1984, 8–13, nos. 5–7; Athens, Acropolis Museum, inv. 599: Stewart 2008a, 385, 408. ↩

- On Kritios and Nesiotes: Muller-Dufeu 2002, nos. 576–84; see also Keesling 2000. ↩

- Zweimüller 2008, 240–43. ↩

- Vlad Borrelli 1966. ↩

- For example, Ridgway 1970. On the reception of Archaic style, Hallett 2012. ↩

- Rolley 1994, 320: “C’est sous l’influence des auteurs latins, qui caractérisent les œuvres des sculpteurs de cette période par les qualificatifs durus, rigidus, austerus, que Winckelmann, dans son Histoire de l’art antique de 1764, qualifie de sévère (streng) la sculpture antérieure à Pheidias…. C’est l’étude fondamentale de V. Poulsen qui a imposé l’expression ‘style sévère’.” For Muller-Dufeu (2002, 171): “le style sévère, en référence à la noblesse d’attitude que les artistes donnent alors à leurs œuvres.” ↩

- Poulsen 1937; Bol 2004a; Germini (2008, 19) attributes the concept of hardness solely to Archaic artistic production, in clear contradiction with the literary sources analyzed. See Lapatin 2012. ↩

- For example, Quintilian Institutio oratoria 11.3.76: staring eyes (rigidi oculi); 11.3.82: head held high, neither rigid nor bowed (cervicem rectam oportet esse, non rigidam aut supinam). ↩

- Winckelmann 1764, ch. 4, section 3, part I.C (Engl. trans., see Winckelmann 2006, 231–32); Donohue 1995; Strocka 2002, 120; Germini 2008, 17. ↩

- Pliny Naturalis historia 34.55–56. Fruitful discussion in Leftwich 1995. ↩

- In general, see La Rocca 1979. On the Doryphoros: von Steuben 1990; on the Diadumenos: Bol 1990; Settis 1992; in general, Franciosi 2003 (with bibliography), to be read with the discerning assessments of Di Cesare 2003. ↩

- The attribution of the Kyniskos statue to Polykleitos is based on Pausanias 6.4.11, since the base in Olympia is not signed. On the inscription: Dittenberger and Purgold 1896, 255–58, no. 149. Borbein (1996, 78) rejects the hypothesis that the Westmacott Boy is linked to the Kyniskos base, for chronological reasons; Stewart (2008c, 167, fig. 84), on the contrary, is open to the possibility of the connection. ↩

- Kaiser 1990; Neumeister (1990, 441) links the meaning of pondus to the concepts of auctoritas and maiestas; see Hölscher 2002. ↩

- Pollitt 1974, 422–23; on aesthetic thought in ancient Greece: Porter 2010; Adornato 2015. ↩

- Kassel, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Antikensammlung inv. Sk 1; Bol 2004a, 29–32, and 2004b; Gercke and Zimmermann-Elseify 2007, 44–50; Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Skulpturensammlung, inv. Hm 49; Knoll, Vorster, and Woelk 2011, 121–31, no. 2 (J. Raeder). ↩

- Adornato 2015. ↩

- Cicero Brutus 70; Quintilian Institutio oratoria 12.7–9; Adornato, forthcoming. ↩

Bibliography

- Adornato 2008

- Adornato, G. 2008. “Delphic Enigmas? The Γέλας ἀνάσσων, Polyzalos and the Charioteer statue.” AJA 112: 29–55.

- Adornato 2010

- Adornato, G. 2010. “Bildhauerschulen: un approccio.” In Scolpire il marmo: Importazioni, artisti itineranti, scuole artistiche nel Mediterraneo antico, ed. G. Adornato, 313–41. Milan: LED Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto.

- Adornato 2015

- Adornato, G. 2015. “Aletheia/Veritas: The New Canon.” In Daehner and Lapatin 2015, 49–59.

- Adornato, forthcoming

- Adornato, G. Forthcoming. “The Invention of Classical Style in Sculpture.” In Handbook of Greek Sculpture, ed. O. Palagia. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Beck, Bol, and Bückling 1990

- Beck, H., P. C. Bol, and M. Bückling, eds. 1990. Polyklet: Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik. Frankfurt am Main: Philipp von Zabern.

- Bol 1990

- Bol, P. C. 1990. “Diadumenos.” In Beck, Bol, and Bückling 1990, 206–12.

- Bol 2004a

- Bol, P. C. 2004. “Der strenge Stil der frühen Klassik. Rundplastik.” In Die Geschichte der antiken Bildhauerkunst: II. Klassische Plastik, ed. P. C. Bol, 1–32. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Bol 2004b

- Bol, P. C. 2004. “Die hohe Klassik: Die großen Meister.” In Die Geschichte der antiken Bildhauerkunst: II. Klassische Plastik, ed. P. C. Bol, 123–43. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Bol 2005

- Bol, R. 2005. “Der Torso von Milet und die Statue des Apollon Termintheus in Myus.” IstMitt 55: 37–64.

- Borbein 1996

- Borbein, A. H. 1996. “Polykleitos.” In Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture, ed. O. Palagia and J. J. Pollitt, 66–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brunnsåker 1971

- Brunnsåker, S. 1971. The Tyrant-slayers of Kritios and Nesiotes: A Critical Study of the Sources and Restorations. 2nd ed. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen.

- Daehner and Lapatin 2015

- Daehner, J. M., and K. Lapatin, eds. 2015. Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; Florence: Giunti.

- De Cesare 2012

- De Cesare, M. 2012. “Pittura vascolare e politica ad Atene e in Occidente: Vecchie teorie e nuove riflessioni.” In Arte-Potere: Forme artistiche, istituzioni, paradigmi interpretativi, ed. M. Castigione and A. Poggio, 97–127. Milan: LED Edizioni.

- Di Cesare 2003

- Di Cesare, R. 2003. Review of Il “Doriforo” di Policleto, by V. Franciosi. ASAtene 81: 720–23.

- Dittenberger and Purgold 1896

- Dittenberger, W., and K. Purgold. 1896. Die Inschriften von Olympia. Berlin: Asher.

- Donohue 1995

- Donohue, A. A. 1995. “Winckelmann’s History of Art and Polyclitus.” In Moon 1995, 327–53.

- Franciosi 2003

- Franciosi, V. 2003. Il “Doriforo” di Policleto. Naples: Jovene Editore.

- Gercke and Zimmermann-Elseify 2007

- Gercke, P., and N. Zimmermann-Elseify. 2007. Antike Steinskulpturen und Neuzeitliche Nachbildungen in Kassel: Bestandkatalog. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

- Germini 2008

- Germini, B. 2008. Statuen des strengen Stils in Rom: Verwendung und Wertung eines griechischen Stils im römischen Kontext. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Hallett 2012

- Hallett, C. H. 2012. “The Archaic Style in Sculpture in the Eyes of Ancient and Modern Viewers.” In Making Sense of Greek Art, ed. V. Coltman, 70–100. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

- Harrison 1985

- Harrison, E. B. 1985. “Early Classical Sculpture: The Bold Style.” In Greek Art: Archaic into Classical, ed. C. Boulter, 40–65. Leiden: Brill.

- Hermary 1984

- Hermary, A. 1984. La sculpture archaïque et classique. Vol. 1: Catalogue des sculptures classiques de Délos. Paris: De Boccard.

- Hölscher 2002

- Hölscher, T. 2002. Il linguaggio dell’arte romana: Un sistema semantico. Turin: Einaudi.

- Kaiser 1990

- Kaiser, N. 1990. “Schriftquellen zu Polyklet.” In Beck, Bol, and Bückling 1990, 48–78.

- Keesling 2000

- Keesling, C. M. 2000. “A Lost Bronze Athena Signed by Kritios and Nesiotes (DAA 160).” In From the Parts to the Whole: Acta of the 13th International Bronze Congress, ed. C. Mattusch, A. Brauer, and S. Knudsen, 69–74. JRA suppl. 39.

- Keesling 2003

- Keesling, C. M. 2003. The Votive Statues of the Athenian Acropolis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Knoll, Vorster, and Woelk 2011

- Knoll, K., C. Vorster, and M. Woelk, eds. 2011. Katalog der antike Bildwerke: Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Vol. 2: Idealskulptur der römischen Kaiserzeit. Munich: Hirmer.

- Kramer 1837

- Kramer, G. 1837. Über den Styl und die Herkunft der bemahlten griechischen Thongefässe. Berlin: Nicolai.

- Lapatin 2012

- Lapatin, K. 2012. “Ancient Writers on Art.” In A Companion to Greek Art, ed. T. J. Smith and D. Plantzos, vol. 1, 273–89. Malden, MA, and Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- La Rocca 1979

- La Rocca, E. 1979. “Policleto e la sua Scuola.” In Storia e civiltà dei Greci: La Grecia nell’età di Pericle: Le arti figurative, ed. R. Bianchi Bandinelli, 517–56. Milan: Bompiani.

- Leftwich 1995

- Leftwich, G. V. 1995. “Polykleitos and Hippokratic Medicine.” In Moon 1995, 38–51.

- Mattusch 2006

- Mattusch, C. C. 2006. “Archaic and Classical Bronzes.” In Greek Sculpture: Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods, ed. O. Palagia, 208–42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moon 1995

- Moon, W. G., ed. 1995. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition. Madison: Wisconsin Studies in Classics.

- Muller-Dufeu 2002

- Muller-Dufeu, M. 2002. La sculpture grecque: Sources littéraires et épigraphiques. Paris: École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

- Neumeister 1990

- Neumeister, C. 1990. “Polyklet in der römischen Literatur.” In Beck, Bol, and Bückling 1990, 428–49.

- Pollitt 1974

- Pollitt, J. 1974. The Ancient View of Greek Art: Criticism, History and Terminology. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Porter 2010

- Porter, J. I. 2010. The Origins of Aesthetic Thought in Ancient Greece: Matter, Sensation, and Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poulsen 1937

- Poulsen, V. H. 1937. Der strenge Stil: Studien zur Geschichte der griechischen Plastik 480–450. Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard.

- Raubitschek 1949

- Raubitschek, A. E. 1949. Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis: A Catalogue of the Inscriptions of the Sixth and Fifth Centuries B.C. Cambridge, MA: Archaeological Institute of America.

- Richter 1951

- Richter, G. M. A. 1951. Three Critical Periods in Greek Sculpture. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ridgway 1970

- Ridgway, B. 1970. The Severe Style in Greek Sculpture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rolley 1994

- Rolley, C. 1994. La sculpture grecque. Vol. 1: Des origines au milieu du Ve siècle. Paris: Picard.

- Settis 1992

- Settis, S. 1992. “Fortuna del Diadumeno: I testi.” NumAntCl 21: 51–76.

- Steuben 1990

- Steuben, H. von. 1990. “Der Doryphoros.” In Beck, Bol, and Bückling 1990, 185–98.

- Stewart 1990

- Stewart, A. 1990. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Stewart 1997

- Stewart, A. 1997. Art, Desire, and the Body in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stewart 2008a

- Stewart, A. 2008. “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 1, The Stratigraphy, Chronology, and Significance of the Acropolis Deposits.” AJA 112: 377–412.

- Stewart 2008b

- Stewart, A. 2008. “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, The Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, The Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning.” AJA 112: 581–615.

- Stewart 2008c

- Stewart, A. 2008. Classical Greece and the Birth of Western Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strocka 2002

- Strocka, V. M. 2002. “Der Apollon des Kanachos in Didyma und der Beginn des strengen Stils.” JdI 117: 81–125.

- Taylor 1991

- Taylor, M. W. 1991. The Tyrant Slayers: The Heroic Image in Fifth Century B.C. Athenian Art and Politics. Salem: Ayer.

- Vlad Borrelli 1966

- Vlad Borrelli, L. 1966. s.v. “Severo, Stile.” Enciclopedia dell’arte antica 7: 228–29. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana.

- Winckelmann 1764

- Winckelmann, J. J. 1764. Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums. Dresden: Walther.

- Winckelmann 2006

- Winckelmann, J. J. 2006. History of the Art of Antiquity. Introduction by Alex Potts, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

- Zweimüller 2008

- Zweimüller, S. 2008. Lukian “Rhetorum praeceptor”: Einleitung, Text und Kommentar. Hypomnemata 176. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.