36. Investigating Ancient “Bronzes”: Non-Destructive Analysis of Copper-Based Alloys

- Robert H. Tykot, University of South Florida, Tampa

Abstract

Identification of the composition of “bronze” objects—many of which are not in fact bronze—is fundamental for studying the technology and intentions of the maker and the availability of tin and other alloys, and for providing accurate descriptive information for museum displays. There are many methods of elemental analysis, but most require the removal of a sample, which increasingly is not allowed for museum-quality objects. The use of a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (pXRF) avoids this, but unfortunately provides results only on the near surface. Readings may be inaccurate due to heterogeneity caused by the cooling process, degradation/weathering, and cleaning or other preservation treatment.

In this study, a Bruker pXRF has been used to analyze hundreds of copper-based objects from different countries and many museums, and the advantages and limitations of this method are discussed in accordance with the research questions being addressed. These include (1) the initial technological transition from copper to arsenical copper and tin bronze alloys, and later to brass; (2) the availability of the secondary metals; and (3) analyses in American museums to assess authenticity and provide accurate descriptive information for display cases.

X-Ray Fluorescence

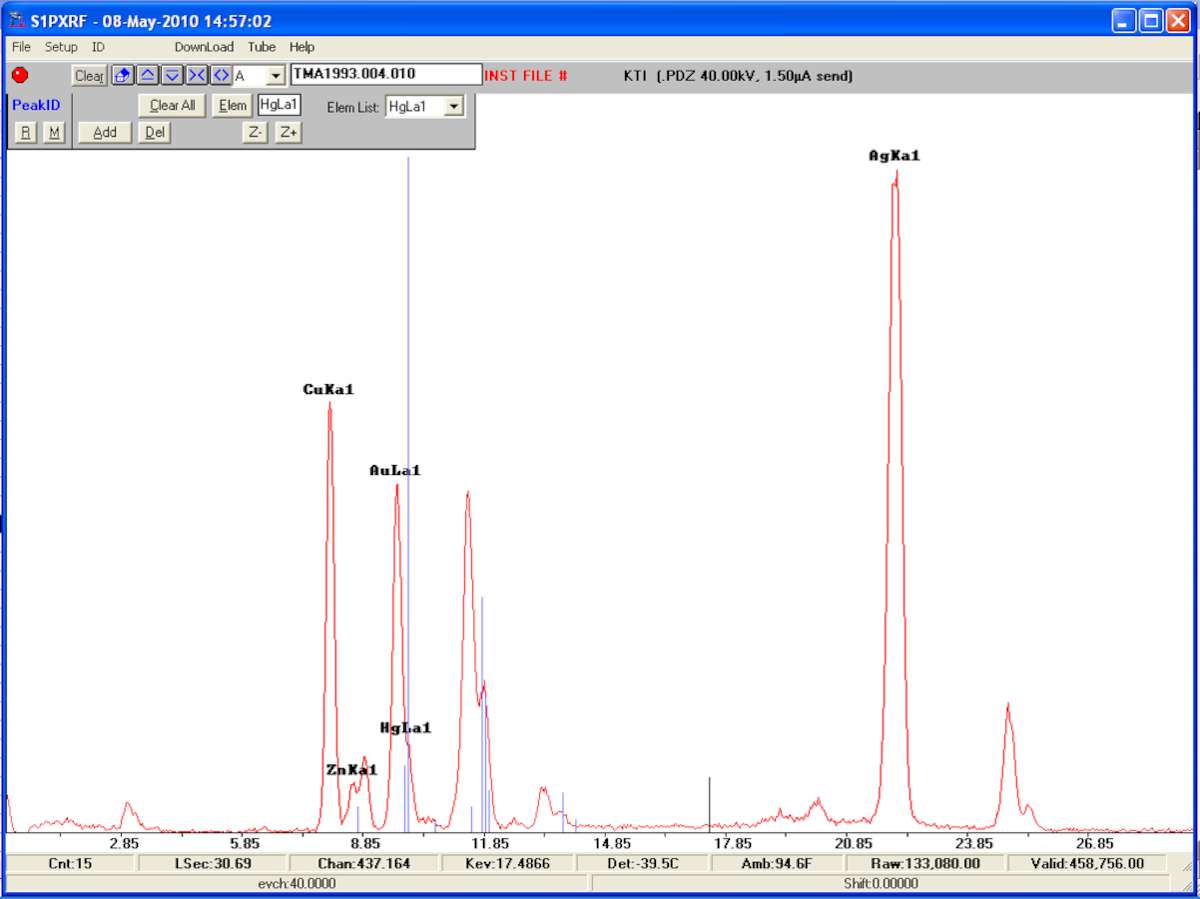

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) is one of many analytical methods used to determine the composition of copper-based metal objects. When used non-destructively, however, care must be taken to understand the principles of this method and thus the significance of the results. XRF analysis involves primary X-rays striking the sample and creating electron vacancies in an inner shell of the atoms; these vacancies are then filled by lower-energy electrons from an outer shell, while producing secondary X-rays. A detector in the XRF instrument measures the energy of these secondary X-rays, which may be identified as coming from specific elements, and the intensity of the peaks, which is proportional to the quantity for each element.1 The depth of penetration of the primary X-rays, and opposite direction for secondary X-rays reaching the detector, are limited to millimeters or less, so that alteration of the metal object’s surface may not quantitatively represent the original composition. Many bronze objects may include more than just copper and tin among the many elements that may be identified (fig. 36.1).

The energy difference between specific atomic shells varies between elements, so that secondary X-rays have characteristic transition energies. The strongest X-ray intensity results from an L-shell electron replacing a K-shell vacancy, and is called Kα, while an M-shell electron replacing a K-shell vacancy is called Kβ. The replacement of L-shell vacancies by M-shell electrons is called Lα. There are also energy differences among the orbitals within each shell, so the X-ray spectra include separate Kα1 and Kα2 lines. There are more L-lines than K-lines for metal elements, and there are substantial energy differences between Lα1, Lα2, Lβ1, Lβ2, and Lγ.

Elemental analysis of copper-based objects requires that the intensity of the primary X-rays be high enough to produce sufficient secondary X-rays for the elements of interest, which for ancient metals include copper (Cu), arsenic (As), tin (Sn), zinc (Zn), lead (Pb), iron (Fe), silver (Ag), antimony (Sb), gold (Au), and mercury (Hg). To quantify the analytical results, filters may be used to reduce the background signal and increase detection limits and precision. For all XRF spectrometers, energy level and intensity are measured by a detector, and the raw data produced may then be calibrated using standards and appropriate software. The standards must also be of copper-based material, as the ability of the secondary X-rays to reach the detector is affected by the composition of the matrix. Standards with a range of values for the other elements (e.g., copper with 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 percent tin; same for lead and others) are also required to produce the most accurate results.

When comparing the different analytical instruments that measure secondary X-rays, there are differences in the size sample that can be accommodated, and the actual area that is analyzed. Scanning electron microscopes and electron microprobes are well known for conducting microanalysis, but in most cases only on small objects that will fit inside the sample chamber. Full-size and desktop XRF instruments analyze a greater area but also have size limitations, while portable XRF spectrometers have no maximum size limit since they are simply held adjacent to the object. While the detection limits of a pXRF may be an order of magnitude less than for regular XRF spectrometers, this does not affect results for major and minor elements in copper-based metal alloys.

Limitations of Non-Destructive Analysis

One important issue to consider is conducting non-destructive surface analyses on potentially heterogeneous samples. Copper-based metals become patinated, and over time may be seriously degraded on the surface, while conservation often involves metallic-based treatments, thus affecting the composition of the object’s surface. When it is not possible to remove a clean sample for elemental analysis, the analysis of multiple spots can quickly reveal if there is significant variability in composition that is not characteristic of the original cast object. Also, the K/L intensity ratios for elements such as tin and copper have fixed values, but these are noticeably altered by corrosion and those spots with irregular values may be excluded. Ideally in such circumstances, it may be permissible to at least clean a small area for reanalysis. Such cleaning is necessary for artifacts known to have been treated with conservation chemicals that contain zinc or other metal elements.

Using a Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometer (pXRF)

Over time, a variety of portable XRF spectrometers have been developed,2 while just in the last decade commercially produced models have been marketed by several major companies. In addition to the limitations of non-destructive XRF on potentially heterogeneous materials, the use of portable XRF spectrometers for archaeological applications has raised some issues about the reliability and comparability of different instruments. In recent years, however, it has been recognized that pXRF spectrometers are as consistent and precise as regular models, and developing calibration for different materials allows for direct comparison with analyses by other analytical methods.3 At this point, the use of pXRF on archaeological metal materials has become widespread, and its regular users have a better understanding of both its potentials and limitations.4

Two different models of the pXRF have been used for the projects discussed in this paper, starting with the Bruker III-V+ in 2007 and the Bruker III-SD in 2012.5 The differences are that the III-SD model uses a silicon drift detector, which is more sensitive and has better resolution than the Si-PIN detector on the III-V+ model. This results in less analytical time necessary per sample and better element identification from the calibration software. For both, the beam size is 5 by 7 millimeters, so that a substantial horizontal area is being analyzed. For the analysis of copper-based metals, a filter made of 12 mil Al and 1 mil Ti was used to enhance the precision of the readings, while settings of 40 kV, 1.5 or 4 μA, and 30–60 seconds were used to provide a full range of metal element peaks with sufficient responses for consistent precise measurements. Experimental testing of the same spot many times has shown that element concentration differences (variation, precision) between analyses are only a fraction of the actual variation in the object.6

Analyses of Copper-Based Alloys

The main purpose of elemental analysis of copper-based metal artifacts is to determine the quantity of elements intentionally included in the alloy. Results obtained from assemblages of copper-based objects may be used for assessing changes in production technology, access to tin and other metals, consistency in alloying different materials (e.g., tools, weapons, jewelry), and recycling practices. Many such artifacts, whether they are tools, weapons, or jewelry, have great artistic and/or archaeological value and are on display in museums. Even for small numbers of objects, analyses provide proper identification and description for both museum exhibits and publications.

One example is a small bronze head (inv. 1984.6) in the collections of Emory University, for which non-destructive analyses were done on three different spots (fig. 36.2). All show that copper is by far the major metal, while the amounts of tin, lead, and silver vary significantly. The crown of hair has much more lead (~14%) and tin (~11%) than the lip area, which has only about 1% lead and 3% tin; neither have any silver. The eye area, however, has about 2–3% silver (and about 4% lead and 7% tin). Several more examples of non-destructive elemental composition research using a portable XRF are presented below.

Bronze Age Sicily

Copper-based artifacts have been infrequently found at Copper-Bronze Age sites in Sicily, whether as tools, weapons, or ornaments, and little if any study has been done on their actual composition. Permission was obtained to conduct non-destructive pXRF analysis on the large collection in the Paolo Orsi Museum in Siracusa, and others in Sicily. Two bowls from the site of Caldare (inv. 16290, 16291) were tested on multiple spots on the inside, outside, and separately attached handles (fig. 36.3). The heavy patina could not be avoided, and the readings for tin on each ranged from 0.7 to 5.7%, and 1.8 to 9.6%. One of the handles had notably more lead (3.0%) and arsenic (0.9%), suggesting a separate initial production process, perhaps with copper from a different source. For a dagger (Caldare inv. 16292), the tin ranges from 1.0 to 7.9% for six spots tested, including a rivet at the base. One spot had a measurable amount of zinc (1.6%), suggesting the use of a preservative. These examples illustrate the limitations of conducting surface analysis on bronzes with heavy patination and/or conservation treatment. Nevertheless, the preliminary results on more than one hundred artifacts analyzed show a great variation in the amount of tin used in the original alloys, which may be explained by tin’s irregular availability in a place so far from any source, and/or the absence of larger-scale production centers and standardized alloying practices.

Viking Age Norway

By the Viking Age, both bronze and brass were widely used. Non-destructive analyses using a pXRF were conducted in the Stavanger Museum, Norway, to test for any patterns and provide information for the museum’s catalogue and display. Among the nearly thirty copper-based objects tested, a cruciform brooch copy stands out as a typical bronze with only tin (9.4%) intentionally added (fig. 36.4). All other items tested were brass, with zinc ranging from just a few percent to more than twenty, and more than half also had tin and/or lead (table 36.1). The range among the percentages for each of these three elements also supports the likelihood of recycling rather than primary production of brass objects.

| Sample | Cu | Zn | As | Pb | Sn | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cruciform brooch | 89.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 9.4 | 0.0 |

| S411 | 73.6 | 24.3 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| S826-1 | 88.1 | 9.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| S826-2 | 80.0 | 16.8 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| S828 | 80.7 | 6.1 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 9.5 | 0.1 |

| S1009 | 86.0 | 11.7 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| S1558 | 80.7 | 16.5 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| S1882 | 85.6 | 8.2 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| S1889 | 88.2 | 9.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| S2095 | 65.6 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 17.4 | 2.6 |

| S2272 | 85.9 | 8.7 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 0.5 |

| S2351 | 77.2 | 19.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| S2552 | 81.4 | 10.4 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| S2820 | 81.9 | 16.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| S2852 | 85.1 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.1 |

| S3162-a | 92.1 | 4.9 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| S3162-b/c | 88.3 | 9.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| S3168 | 82.4 | 11.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| S3237 | 75.8 | 22.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| S3426 | 82.4 | 15.7 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| S3857 | 81.7 | 16.5 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| S4083 | 80.1 | 10.1 | 0.0 | 8.4 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| S4140 | 76.5 | 14.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 7.7 | 0.2 |

| S4690 | 82.5 | 13.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| S7129 | 84.8 | 6.0 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 1.1 |

| S8352 | 84.8 | 9.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| S12295 | 67.8 | 6.2 | 1.0 | 15.9 | 5.3 | 2.5 |

| S12720 | 70.6 | 8.0 | 2.6 | 10.7 | 5.9 | 1.0 |

On-site Analysis in Calabria Using pXRF

In most cases, a sample should be cleaned prior to compositional analysis, to avoid contamination issues. But for copper-based objects, any “dirt” is not likely to affect significantly the proportions of copper, tin, lead, and other metallic elements other than iron. On-site analyses can therefore produce reliable estimated results that may immediately be shared with the excavation team, local officials, and visitors. At the Greek settlement site of Francavilla Marittima in Calabria, Italy, excavations uncovered a burial (grave 14) with what appeared to be copper-based metal artifacts (objects 999‒1000) (fig. 36.5). Analyses were conducted at the site the same day, revealing both to be tin bronzes (11 and 13% Sn) with no arsenic, lead, or zinc added.

Analysis of a Native American Tablet

An incised Native American–style metal tablet was found at the near-contact-period Blueberry site (8HG678) in the Kissimmee Valley of south-central Florida (fig. 36.6). Analyses were conducted to determine whether it had been made by the Belle Glade people using native copper (that is, pure, geologically natural copper), or using smelting and casting technology, which was introduced to North America after European contact. Multiple spot analyses on both sides by pXRF showed virtually pure copper, more so than for typical smelted copper artifacts, which often have some iron, calcium, and other elements left from the slag. It also would have been more likely that the use of European-produced metal would have come from an alloy rather than pure copper.

“Bronzes” in Florida Art Museums

Most of the Greek, Roman, Latin American, and other metal artifacts on display in museums in the United States were acquired through purchase or by donation and not from excavations, so there are questions about their original archaeological context as well as their authenticity. Using a pXRF, nearly all metal artifacts in the Tampa Museum of Art (80 objects, mostly Greek and Roman) and the Orlando Museum of Art (125 South American objects) were analyzed to assess authenticity and in all cases to provide compositional information for display labels and future research.

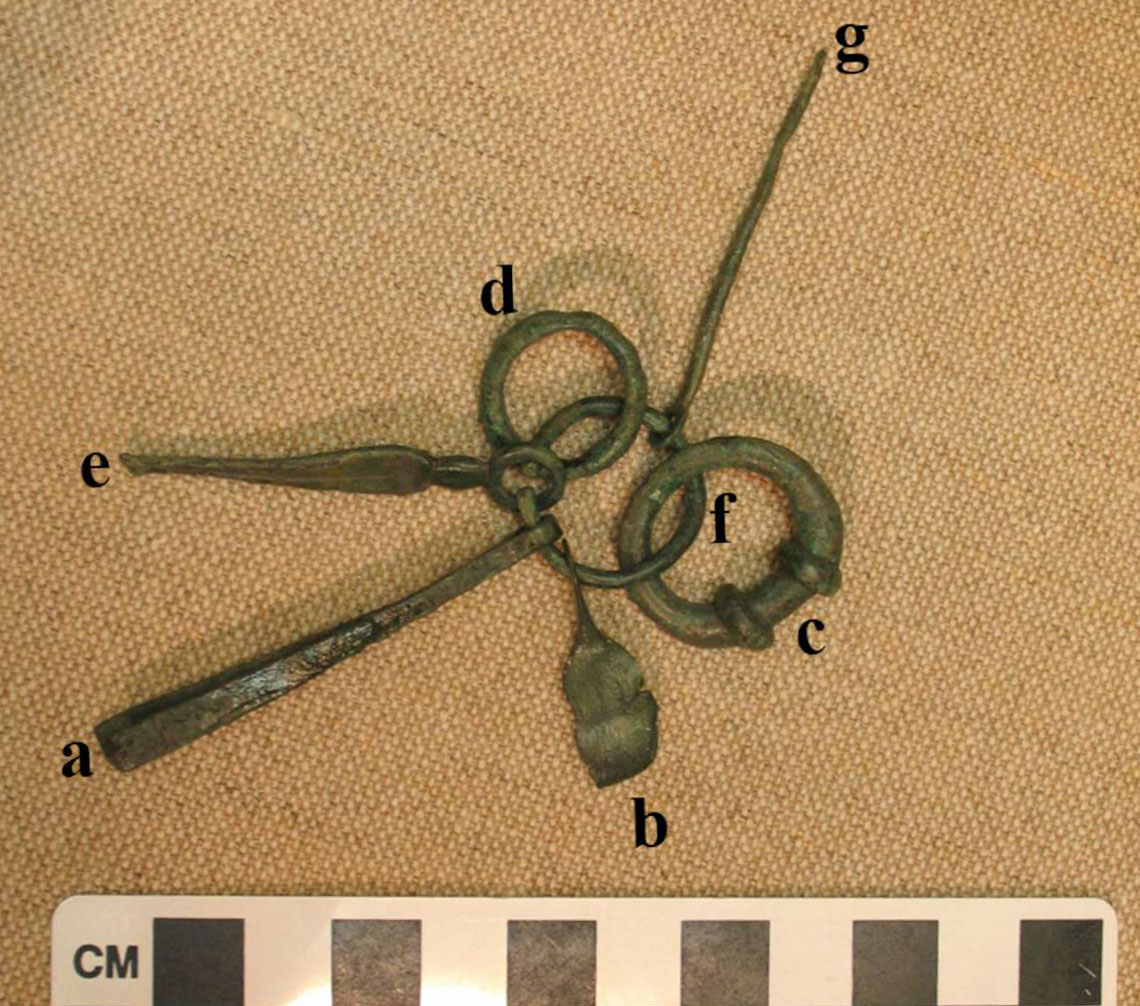

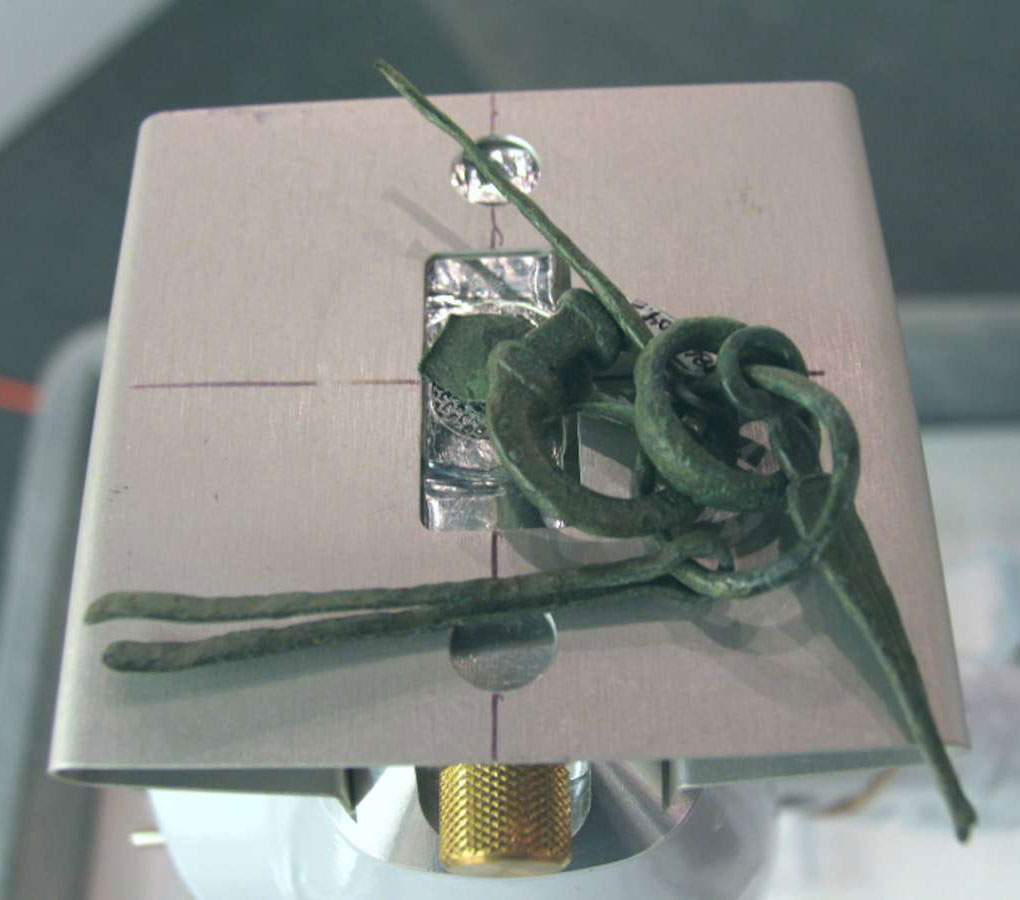

In the Tampa Museum, two northern Greek bracelets (TMA 1996.024.001/2) have consistent values with about 8% tin and 1% lead, which was common in the Iron Age (fig. 36.7b). A Roman “bronze” strigil (TMA 1982.022) has no tin but more than 20% zinc, so it is actually brass (fig. 36.7a). Retesting is planned to check if the zinc may be from a conservation treatment prior to its donation to the museum, but the lack of tin would make it unusual for first-century AD Roman finds. Each of the seven pieces of the chatelaine (TMA 1986.204a‒g), also assigned to about 100 AD, has a substantially different tin composition, and thus may be interpreted as a compilation of separately made items (fig. 36.7c–d). All have high copper and tin, while one has especially high lead content (1986.204e). A “bronze” crossbow fibula (TMA 1993.004.010), assigned to the fourth century AD western Roman Empire at least needs much better labeling, as it includes zinc, gold, mercury, and silver, but no tin (fig. 36.8)!

The Orlando Museum has many metal objects labeled as “gold” but analyses by pXRF show that most are actually alloys, with high percentages of silver and copper as well (OMA 2003.078.1-2) (fig. 36.9a). Many others are listed as tumbaga (Cu-Ag-Au alloy), but contain no gold or silver (table 36.2). Starting in pre-Inca times, depletion gilding—involving acid treatment and oxidation of the surface—was used to make the immediate surface mostly gold, so XRF analyses result in varying concentrations depending on depth. Many other objects in the museum were simply labeled as “copper” or “metal,” with analyses revealing many that are arsenical copper (OMA 2004.104.1-4), fig. 36.9b), and just a few that are bronze (with just 2–3% Sn) (OMA 2004.032) (fig. 36.9c). One artifact, a knife (OMA 2004.074), has a high percentage of zinc, which was not used in Moche (pre-Columbian) times in the Americas, and thus is not authentic (fig. 36.9d).

| OMA No. | Object Description | Cu | Sn | As | Pb | Ag | Au | Fe | Zn | Ca |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002.018 | Botanical frog bead, AD 700–1000, Moche. Gold | 13.2 | 14.6 | 72.3 | ||||||

| 2002.057 | Teeth design mouthpiece, AD 300–700, Moche. Gold | 27.8 | 17.0 | 55.2 | ||||||

| 2003.078.1 | Plume, AD 300–700, Nasca. Gold | 1.9 | 29.8 | 68.3 | ||||||

| 2003.078.2 | Plume, AD 300–700, Nasca. Gold | 4.5 | 23.0 | 72.6 | ||||||

| 2004.029 | Ornament, AD 100–300, Chimu. Copper | 93.0 | 4.1 | 3.0 | ||||||

| 2004.03 | Ring with two birds, AD 1100–1400, Chimu. | 97.4 | 2.6 | |||||||

| 2004.032 | Crocodile tumi, AD 1100–1400, Chimu. Copper/tumbaga | 97.7 | 2.3 | |||||||

| 2004.052 | Tumi, AD 1100–1400, Lambayeque/Chimu. Copper | 90.4 | 5.7 | 2.0 | 1.9 | |||||

| 2004.053 | Tumi, AD 200–700, Lambayeque/Chimu. Copper/tumbaga | 98.1 | 1.9 | |||||||

| 2004.054 | Tumi, AD 200–700, Lambayeque/Chimu. Copper/tumbaga | 98.5 | 1.5 | |||||||

| 2004.071 | Spoon, AD 200–500 | 95.0 | 5.0 | |||||||

| 2004.074 | Top of knife, AD 450–550, Moche. Copper | 46.4 | 1.7 | 8.0 | 35.2 | 8.7 | ||||

| 2004.080.1 | Ear spools, AD 1100–1400, Moche? Copper | 60.4 | 1.0 | 38.5 | ||||||

| 2004.080.2 | Ear spools, AD 1100–1400, Moche? Copper | 42.7 | 0.7 | 56.6 | ||||||

| 2004.096 | Vessel of a figure, AD 200–400, Nasca | 2.4 | 31.2 | 66.4 | ||||||

| 2004.097 | Tweezers, AD 500–800, Nasca. Gold | 3.7 | 24.9 | 71.4 | ||||||

| 2004.104.1 | Metal needle, AD 1000–1500, Chancay | 92.6 | 7.4 | |||||||

| 2004.104.2 | Metal needle, AD 1000–1500, Chancay | 98.1 | 1.9 | |||||||

| 2004.104.3 | Metal needle, AD 1000–1500, Chancay | 95.0 | 5.0 | |||||||

| 2004.104.4 | Metal needle, AD 1000–1500, Chancay | 94.3 | 5.7 | |||||||

| 2004.112.1 | Bird bead, AD 1100–1400, Chimu. Metal | 97.2 | 2.8 | |||||||

| 2004.112.2 | Bird bead, AD 1100–1400, Chimu. Metal | 94.6 | 5.4 | |||||||

| 2004.112.3 | Bird bead, AD 1100–1400, Chimu. Metal | 97.0 | 3.0 | |||||||

| 2004.112.4 | Bird bead, AD 1100–1400, Chimu. Metal | 86.4 | 11.7 | 1.8 |

Etruscan Bronze Mirrors in the Southeast United States

Shiny bronze mirrors were widely produced by the Etruscans, and many have been found in their tombs. Typically decorated on one side and smooth on the other, there are many now in American museums (fig. 36.10a–b). Testing by pXRF has been used to assess the composition for Etruscan mirrors in American museums, as well as to further test the hypothesis that many may be fakes.7 Analyses have been done on more than thirty mirrors in the Smithsonian, Johns Hopkins University, the Walters Art Museum, the Baltimore Museum of Art, Emory University, the Tampa Museum of Art, and the Ringling Museum in Sarasota. Many are known to have been treated with a preservative, but analyzing multiple spots has allowed us to avoid that issue while addressing potential differences between the mirror sides and also with attached decorated handles (fig. 36.10c). From the results obtained, it appears that in earlier Etruscan times, the amount of tin used was similar to that for bronze tools (~8–15%), while by the third century BC there was a big increase in the tin (~20–30%) and therefore the reflectiveness of the mirror. While many of the mirrors in these museums are thought to be fakes, based on their style, only a few have incompatible chemical compositions (with zinc).

a

a

b

b

c

c

Conclusion

The use of non-destructive analytical techniques provides many opportunities for studying bronze and other objects in museums and other places around the world. The examples presented here illustrate some of the specific questions that knowledge of the composition of copper-based materials can answer. The user and readers of their reports, however, must realize that while the precision and accuracy of pXRF instrumental results are high, there remain limitations in the interpretation of the values taken from copper alloys with patinated and degraded surfaces.

Acknowledgments

I appreciate very much the assistance of Robert Bowers on creating copper-based metal calibration curves; colleagues Nancy de Grummond, Martin Guggisberg, Mads Ravn, Renee Stein, and Andrea Vianello for their roles in the case studies presented in this article; and the many officials and museum staff involved in providing permission and access to the objects for these non-destructive analyses. Funding for some of this research comes from Emory University, Florida State University, and the University of South Florida.

Notes

- Ciliberto and Spoto 2000; Pollard et al. 2007; Pollard and Heron 2008; Missouri University Archaeometry Lab 2015. ↩

- Karydas 2007. ↩

- Gliozzo et al. 2010, 2011. ↩

- Dylan 2012; Goodale et al. 2012; Shugar and Mass 2012; Liritzis and Zacharias 2013; Shugar 2013; Charalambous, Kassianidou, and Papasavvas 2014; Dussubieux and Walker 2015; Orfanou and Rehren 2015; Freund, Usai, and Tykot 2016; Garrido and Li 2016. ↩

- Bruker 2015. ↩

- Tykot 2016. ↩

- Tykot, de Grummond, and Schwarz 2012 ↩

Bibliography

- Bruker 2015

- Bruker. 2015. “Tracer Series pXRF Spectrometer” (April 30, 2015). https://www.bruker.com/products/x-ray-diffraction-and-elemental-analysis/handheld-xrf/tracer-iii/overview.html

- Charalambous, Kassianidou, and Papasavvas 2014

- Charalambous, A., V. Kassianidou, and G. Papasavvas. 2014. “A Compositional Study of Cypriot Bronzes Dating to the Early Iron Age Using Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (pXRF).” JAS 46: 205–16.

- Ciliberto and Spoto 2000

- Ciliberto, E., and G. Spoto, eds. 2000. Modern Analytical Methods in Art and Archaeology. New York: Wiley.

- Dussubieux and Walker 2015

- Dussubieux, L., and H. Walker. 2015. “Identifying American Native and European Smelted Coppers with pXRF: A Case Study of Artifacts from the Upper Great Lakes Region.” JAS 59: 169–78.

- Dylan 2012

- Dylan, S. 2012. “Handheld X-ray Fluorescence Analysis of Renaissance Bronzes: Practical Approaches to Quantification and Acquisition.” In Shugar and Mass 2012, 37–74.

- Freund, Usai, and Tykot 2016

- Freund, K. P., L. Usai, and R. H. Tykot. 2016. “Early Copper-Based Metallurgy at the Site of Monte d’Accoddi (Sardinia, Italy).” 41st International Symposium on Archaeometry, Kalamata, Greece, May 15–20. Abstract published in 41st International Symposium on Archaeometry Book of Abstracts, ed. N. Zacharias and E. Palamara, 258–59. Kalamata, Greece.

- Garrido and Li 2016

- Garrido, F., and T. Li. 2016. “A Handheld XRF Study of Late Horizon Metal Artifacts: Implications for Technological Choices and Political Intervention in Copiapó, Northern Chile.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 8:1–8. DOI: 10.1007/s12520-016-0315-2.

- Gliozzo et al. 2010

- Gliozzo, E., R. Arletti, L. Cartechini, S. Imberti, W. A. Kockelmann, I. Memmi, R. Rinaldi, and R. H. Tykot. 2010. “Non-invasive Chemical and Phase Analysis of Roman Bronze Artefacts from Thamusida (Morocco).” Applied Radiation and Isotopes 68: 2246–51.

- Gliozzo et al. 2011

- Gliozzo, E., W. A. Kockelmann, L. Bartoli, and R. H. Tykot. 2011. “Roman Bronze Artefacts from Thamusida (Morocco): Chemical and Phase Analyses.” Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B 269: 277–83.

- Goodale et al. 2012

- Goodale, N., D. G. Bailey, G. T. Jones, C. Prescott, E. Scholz, N. Stagliano, and C. Lewis. 2012. “pXRF: Study of Inter-instrument Performance.” JAS 39: 875–83.

- Karydas 2007

- Karydas, A. G. 2007. “Application of a Portable XRF Spectrometer for the Non-invasive Analysis of Museum Metal Artefacts.” Annali di Chimica 97: 419–32.

- Liritzis and Zacharias 2013

- Liritzis, I., and N. Zacharias. 2013. “Portable XRF of Archaeological Artifacts: Current Research, Potentials and Limitations.” In X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (XRF) in Geoarchaeology, ed. M. S. Shackley, 109–42. New York: Springer.

- Missouri University Archaeometry Laboratory 2015

- Missouri University Archaeometry Laboratory. 2015. “Overview of X-ray Fluorescence” (April 30, 2015). Missouri University Archaeometry Laboratory. http://archaeometry.missouri.edu/xrf_overview.html

- Orfanou and Rehren 2015

- Orfanou, V., and T. Rehren. 2015. “A (Not So) Dangerous Method: pXRF vs. EPMA-WDS Analysis of Copper-based Artefacts.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 7: 387–97.

- Pollard et al. 2007

- Pollard, A. M., C. Batt, B. Stern, and S. M. M. Young. 2007. Analytical Chemistry in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pollard and Heron 2008

- Pollard, A. M., and C. Heron, eds. 2008. Archaeological Chemistry. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Shugar 2013

- Shugar, A. N. 2013. “Portable X-ray Fluorescence and Archaeology: Limitations of the Instrument and Suggested Methods to Achieve Desired Results.” In Archaeological Chemistry VIII, ed. R. A. Armitage and J. H. Burton, 173–95. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society.

- Shugar and Mass 2012

- Shugar, A. N., and J. L. Mass, eds. 2012. Handheld XRF for Art and Archaeology. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Tykot 2016

- Tykot, R. H. 2016. “Using Non-Destructive Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometers on Stone, Ceramics, Metals, and Other Materials in Museums: Advantages and Limitations.” Applied Spectroscopy 70(1): 42–56.

- Tykot, de Grummond, and Schwarz 2012

- Tykot, R. H., N. T. de Grummond, and S. J. Schwarz. 2012. “XRF Analysis of Metal Composition of Etruscan Bronze Mirrors.” Abstract published in Archaeological Institute of America 113th Annual Meeting Abstracts 35: 71–72.