37. A Scientific Assessment of the Long-Term Protection of Incralac Coatings on Ancient Bronze Collections in the National Archaeological Museum and the Epigraphic and Numismatic Museum in Athens, Greece

- Stamatis C. Boyatzis, Technological Educational Institute of Athens, Department of Conservation of Antiquities & Works of Art, Egaleo, Greece

- Andriana Veve, Technological Educational Institute of Athens, Department of Conservation of Antiquities & Works of Art, Egaleo, Greece

- Galateia Kriezi, Technological Educational Institute of Athens, Department of Conservation of Antiquities & Works of Art, Egaleo, Greece

- Georgia Karamargiou, National Archaeological Museum, Greece

- Elena Kontou, Epigraphic and Numismatic Museum, Athens, Greece

- Vasilike Argyropoulos, Technological Educational Institute of Athens, Department of Conservation of Antiquities & Works of Art, Egaleo, Greece

Abstract

Introduction

Among the main criteria for selecting a coating for cultural heritage metal artifacts are (1) long-term insulation of their surfaces from contaminants due to environmental pollutants and handling; (2) the filtration of light through absorption of radiation; (3) considerable adhesion to the metal surface and elasticity; and finally (4) chemical stability. Ease of application and reversibility are also among the highly sought requirements.

Incralac was introduced by INCRA (International Copper Research Association) in 1964 as a metal protective coating based on the acrylic resin Paraloid B44 (an ethylacrylate –methylmethacrylate copolymer) with benzotriazole (BTA) as a main additive. It has been widely used in conservation as meeting the above requirements.1 In addition to these compounds, small quantities of a stabilizer (i.e., crosslinker) such as epoxidized soybean oil (ESO), as well as hindered amine light stabilizers (HALS) such as Tinuvin 292, are occasionally added for conservation application.2 Long-term for Incralac coating typically means 5 to 8 years according to the manufacturers; however, museums rarely find the time to recoat their objects, and coatings are routinely used for longer periods of time than normally recommended by the manufacturer.

Conservation practice studies have shown that the protection that Incralac offers to outdoor bronze objects is only temporary, as various problems can arise with prolonged use, such as brittleness of the coating and irreversibility with solvents.3 On the other hand, its indoor use appears to result in more enduring protection, as attested by many conservators.

A survey in 20064 found that museums in Greece show a preference for Incralac as a coating for ancient bronze objects in museums. Also, this coating has been routinely applied on both indoor and outdoor bronzes worldwide. As most conservators in Greece attest to its good performance as a long-term coating on ancient bronzes, this study was initiated to better understand the behavior of this coating for indoor bronze collections. Many studies have looked at the stability of this coating, with varying results.5 One major study tested various coatings, such as Incralac (with and without corrosion inhibitors) and BTA, on copper-alloyed panels with accelerated aging (indoor and outdoor conditions), and at outdoor test sites at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, the Swedish Corrosion Institute in Stockholm, and in Tirgu Jiu in Romania.6 The study found Incralac to be one of the best coatings in both outdoor tests and indoor accelerated-aging trials, but the prior application of a corrosion inhibitor such as BTA was found not to have any beneficial effect on the coating’s behavior.

Aims of the Work

This work aims to better understand the condition of Incralac coatings on bronze artifacts on display or in storage at the National Archaeological Museum and the Epigraphic and Numismatic Museum, both located in Athens, Greece, on the basis of year of application and treatment practice. Also, the research tried to correlate the results with artificial aging of Incralac on bronze coupons from different vendors in Greece.

Experimental Section: Materials and Specimens

Solvents: All solvents were Sigma-Aldrich, reagent grade: acetone, methyl-ethyl ketone, dichloromethane.

Coatings and Bronze Coupons: A number of Incralac products were acquired especially for this research from typical distributors throughout Greece that sell conservation materials. For the sake of anonymity, these distributors are referred to below as A, B, C, D, and E.

Bronze coupons (63.81% Cu and 36.19% atom by SEM-EDX analysis) were prepared from larger bronze blocks and were cut into smaller specimens (2.0 x 2.0 x 0.03 cm). Accordingly, they were polished using SiC sandpapers successively with decreasing mesh diameter (P2400 and P4000).

Incralac coatings were applied to the bronze coupons using a do-it-yourself spin coater at an average of 1000 rpm (measured by a laser tachometer). This way, uniform films of 1.16–1.36 μm thickness were cast from their methyl-ethyl ketone (MEK) solutions (10% w/w) on each coupon.

Artificial Aging Conditions: An artificial aging protocol was employed involving heat, moisture, and UV-visible light to simulate average external conditions on a day-night succession basis. In particular, the following cycles were utilized: Low-to-mid humidity cycle (Cycle 1): 70°C, 60% RH, 7.5 days (UV-vis light was turned on and off every 22.5 min). High humidity cycle (Cycle 2): 70°C, 95% RH, 7.5 days (UV-vis light was turned on and off every 22.5 min).

Analytical Techniques: SEM-EDX analysis was done with a JEOL JSM-5310 system. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of Incralac films were recorded (64 scans, 4 cm cm–1 resolution) using a PerkinElmer Spectrum GX I FTIR spectrometer as follows: (a) reflection-absorption spectra of artificially aged films on polished bronze were recorded using a PerkinElmer fixed angle (approx. 218) reflection accessory; the two mirrors allowed for manual angle optimization to achieve maximum energy throughput. The variability of film thickness in spin-coated bronze coupons was tested with recording FTIR spectra (64 acquisitions using a circular window of 2 mm diameter on the fixed angle accessory) of five different spots on each coupon and the absorbance areas at 1740–1720 cm–1 range were accordingly calculated.

FTIR spectra of corrosion products from museum objects were recorded from detached powder samples, wherever possible, which were accordingly pressed into a KBr disc. Spectra of coatings from museum objects were recorded from their acetone (Merck, Pro-analysis) extracts, which were accordingly applied on clean KBr discs.

Results and Discussion: Incralac Formulations and Artificial Aging

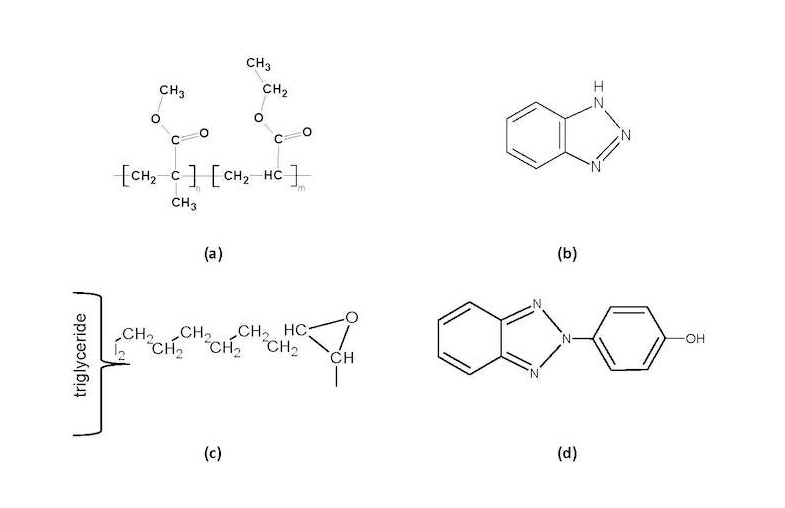

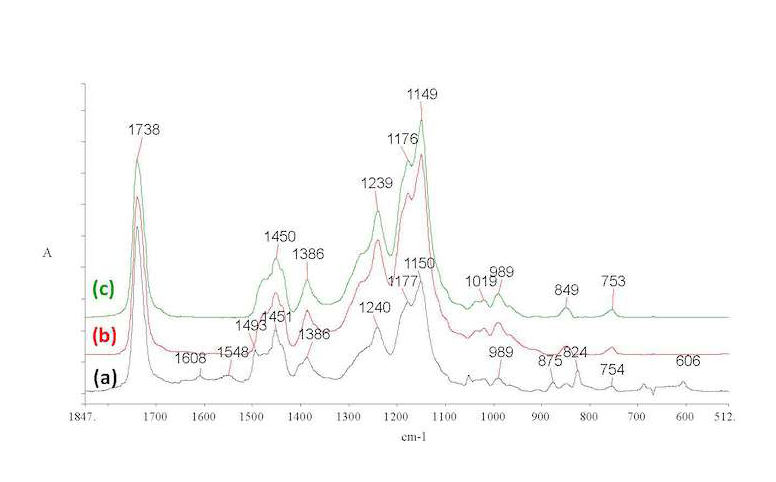

It is crucial to investigate the actual formulations of the materials available in the market, as well as their behavior under simulated aging conditions, before any further analysis is conducted on actual artifacts in order to ensure that results do not vary due to different formulations. Incralac has been formulated as a coating containing acrylic resin (Paraloid B44) as its base component and additives such as BTA or an aryl-substituted derivative. A few other materials are frequently added, such as ESO and Tinuvin 292 (T). Chemical structures of involved materials are shown (fig. 37.1); FTIR spectra of studied Incralac formulations are shown in fig. 37.2a; FTIR peak assignments are given in table 37.2.

It has been previously suggested that Incralac formulations, at least at the acrylic resin level, may vary from supplier to supplier.7 In our investigations, a number of Incralac batches were analyzed with KBr-FTIR and results confirm this suggestion. Figure 37.2a shows the recorded spectra of Incralac products acquired from various distributors in Greece (table 37.1). It can be seen that the basic formulation is similar in most cases, with Paraloid B44 being the base acrylic resin, with main absorptions at 2989, 2953, and 2846 cm–1 (antisymmetric stretching of CH3 and CH2 and symmetric stretching of CH2, correspondingly); 1732 cm–1 (ester carbonyl stretching); 1474, 1449, and 1387 cm–1 (CH2 and CH3 bending); and 1238, 1177, and 1147 (C-O-C stretching).

| Distributor | Base acrylic resin | Additives |

|---|---|---|

| A | Paraloid B44 | Very low amounts of substituted benzotriazole, epoxidized soybean oil |

| B | Paraloid B44 | Substituted benzotriazole, epoxidized soybean oil |

| C | Paraloid B44 | Substituted benzotriazole, epoxidized soybean oil |

| D | Different resin, possibly Paraloid B48N | Substituted benzotriazole, epoxidized soybean oil |

| E | Paraloid B44 | Substituted benzotriazole, epoxidized soybean oil |

| F | Paraloid B44 | Substituted benzotriazole, epoxidized soybean oil |

| Incralac Absorption Maxima (cm–1) | Assignment1 |

|---|---|

| Carbonyl ester harmonic | |

| 2989, 2953, 2846(sh) | vas CH3, vasCH2, vsCH2 in base acrylic resin (Paraloid B44) 2 |

| 2926 | vas CH2 from oil, possibly ESO4 |

| 2875 | vs CH3 (due to presence of t–butyl methacrylate in Paraloid B48N; found in one case, see text) 2 |

| 1732 | v C=O in base acrylic resin2 |

| 1604 | v C=C in aromatic ring of BTA3 |

| 1548 | δ NH |

| 1494 | v C=C (aryl ring) |

| 1474 | δ CH2 main chain in base acrylic resin2 |

| 1449 | δ CH3-CH2-O side chain + δas CH3 in base acrylic resin2 |

| 1387 | δs CH3 side chain in base acrylic resin2 |

| 1265 | v C-O in epoxy ring in ESO5 |

| 1238, 1177, 1147 | v C-O-C in base acrylic resin2 |

| 1027 | v C-C-O in base acrylic resin2 |

| 990 | δ Η-C-Η, τ CH3 in base acrylic resin |

| 875 | δoop C-H in substituted aryl ring in BTA3 |

| 848 | δ C-C-CH3 (α-CH3 of EMA in base acrylic resin)2 |

| 824 | δ (CCO) in epoxy ring in ESO5 |

| 753 | δoop C-C=O |

| 688 | Aromatic ring vibration in BTA3 |

| 606 | Triazole ring vibration in BTA3 |

| |

Added quantities of BTA (possibly an aryl-substituted derivative as evidenced by the peaks at 1604, 1548, and 1494 cm–1) and of an epoxy-oil compound (possibly epoxidized soybean oil, based on distributors’ data sheets and the literature, and evidenced by the 2926 and 1265 cm–1 peaks) are also detected. (For FTIR peak assignments, see table 37.2.) In one specific case (distributor A), lower amounts of additives were detected through FTIR analysis than for the other distributors, while in another (distributor D), a different base polymer seems to have been used or added, possibly Paraloid B48N (based on its 2961, 2876 C-H stretching absorption peaks pattern).8 On this basis, it may be hypothesized that some manufacturers or distributors formulate their own Incralac-type products by employing primarily Paraloid B44 (and in one case a different resin) and adding substituted BTA and/or epoxidized soybean oil (ESO); also, addition of other unspecified additive(s) in small quantities cannot be ruled out.

The performance of various Incralac formulations was evaluated through artificial aging of spin-coated films on polished bronze coupons, where accelerated aging simulating day-night sequences was applied in two consecutive overall aging cycles (see Experimental Section for conditions). As seen in reflection FTIR spectra of their films (figs. 37.2b–c), after artificial aging Cycle 1 (see fig. 37.2b) all coupons showed dramatically lower BTA levels as compared to those of the initial materials (see fig. 37.2a), while after Cycle 2, BTA seems to have been completely removed (see fig. 37.2c). Sublimation of the material is a possible explanation as suggested in the literature and may lead to depletion of the anti-corrosion components in the formulation.9 Therefore, the decrease and eventual disappearance of BTA in the coating over prolonged application times is possibly a more significant factor than the aging of the resin material itself.

Investigating the Condition of Incralac in Bronze Museum Objects

Objects from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens: Eight bronze objects from the collection of the National Archaeological Museum were selected on the basis of their previous conservation treatments with Incralac formulations (see object photos in fig. 37.3). In particular, the sample contained a jug (fig. 37.3a, Χ 7934, Greece, fifth century BC); a statuette complex with goddess Isis with Horus (fig. 37.3b, X 1974, Egypt, 26th–30th Dynasty, 600–300 BC); a mirror (fig. 37.3c, Χ 21039, unknown origin); a kyathos (fig. 37.3d, Χ 26175, Greece, end of 7th–beginning of 6th century BC); a ring (fig. 37.3e, Χ 25604, unknown origin); a spiral bracelet (fig. 37.3f, Χ 17166, Greece, possibly Geometric era); a strigil (fig. 37.3g, Χ 8297, Greece, fifth century BC); and a sword (fig. 37.3h, Π 7317, Greece, end of fifteenth–fourteenth century BC).

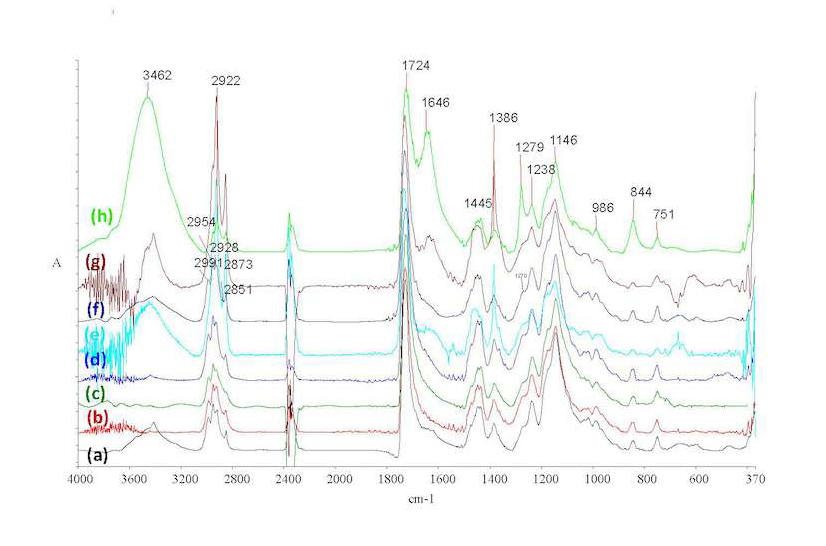

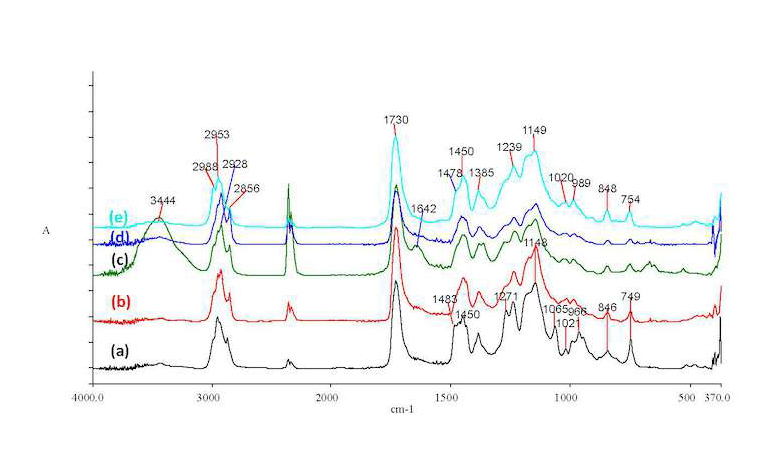

FTIR spectra were recorded from acetone-extracted coating samples (see Experimental Section). As shown in figure 37.4, no BTA could be detected in all cases in the coating, as no characteristic peaks of the component were present; this may be due either to decrease or removal of the additive in a manner similar to that of artificial aging of coated bronze coupons (see above), or to the limited or ineffective extraction of this particular component through the selected solvent during sample collection. In addition, in some cases (objects X 1974, X 21039, and X 8297) the condition of coatings was found to be only slightly changed or totally unchanged compared to the initial condition of the base acrylic resin. However, in other cases (objects Χ 26175, Χ 17166, and Χ 25604), significant formation of hydroxyl absorptions (broad features at 3500–3200 cm–1) indicate oxidation and/or hydrolytic degradation of esters. The latter can be ruled out, as absorption of polyacrylate copper salts at the 1600–1550 cm–1 range10 is not evident. The newly formed band at ca. 1646 cm–1, which was particularly intense in the case of object Χ 17166 (conserved in 1998–99 using Incralac material from distributor E), was assigned to C=C absorptions due to oxidation-induced unsaturation in the acrylic resin backbone; additionally, the dark reddish appearance of this object’s coated surface (see fig. 37.3f) supports this assignment. Relatively high degradation levels were also detected in objects Χ 25604 and X 25175, which were attributed to the same factors. In accordance with the conservation records, it can be assumed that the poor coating performance resulted from the failure to stabilize the object with corrosion inhibitor BTA, rather than being an effect of the coating itself, as material from the same distributor performed better in other cases. This assumption contradicts another study,11 but that study was on test panels and not on real archaeological bronzes as in our case. Stabilization of bronzes using corrosion inhibitor BTA is routinely carried out in Greece prior to Incralac application, and the combined use of BTA and Incralac is highly recommended by conservators in Greece for its effectiveness.

| Registry # | Description | Region and Historical Period | Year of Conservation | Pre-treatment | Application of Coating | Arbitrary grading | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Chemical | Stabilization | Incralac Solvent | Incralac Concentration (%) | Matting Agent | Distributor | SEM Analysis1 | FTIR Analysis of Corrosion Products1 | FTIR Analysis of Coating | Degradation Grading2 | ||||

| X 7934 | Jug | Greece, 5th c. BC | 1979 | Yes | No | BTA | Toluene | ? | Yes | E or F | Cu, Al, Si, Fe, Mg, Ca, S | Calcite, silicates, copper oxides | Low levels of degradation: mainly hydrolytic and depolymerization | 4 |

| X 1974 | Statuette, Isis with Horus | Egypt, 26th–30th Dynasty (600–300 BC) | 1985 | Yes | Yes | BTA | Toluene | ? | No | E or F | Cu, Sn, Pb, Al, Ca, Cl | Copper oxides and hydroxides, traces of organic coating, moisture | No sign of degradation | 0 |

| Χ 21039 | Mirror | ? | 1991 | Yes | No | BTA | Toluene | ? | No | E or F | Cu, Pb, Al, Si, Fe, Ca | Copper oxides, malachite | Very low levels of degradation | 1 |

| Χ 26175 | Kyathos | Greece, end of 7th – beginning of 6th c. BC | 1998 | Yes | No | BTA | Toluene | 8–10 | Yes | A | N.A. | N.A. | Low levels of degradation: mainly hydrolytic and depolymerization; also signs of bio-degradation (formation of nitrates) | 4 |

| Χ 25604 | Ring | ? | 2000 | Yes | No | No | Toluene | 8–10 | Yes | E | N.A. | N.A. | High levels of degradation: mainly hydrolytic and depolymerization; also signs of bio-degradation (formation of nitrates) | 5 |

| Χ 17166 | Kringle | Greece, possibly Geometric period | 1999 | No | Yes | No | Toluene | 8–10 | Yes | E | N.A. | N.A. | Significantly high levels of degradation: mainly hydrolytic and depolymerization | 9 |

| Χ 8297 | Strigil | Greece, 5th c. BC | 1997 | Yes | No | BTA | Toluene | ? | Yes | E | Cu, Sn, Al, Ca , S, P, Si | Malachite, organic coating residue | Very low levels of degradation | [BLANK] |

| Π 7317 | Sword | end of 15th–beginning of 14th c. BC | 2003 | Yes | No | No | Toluene | 8–10 | No | A | Cu, Sn Al, Si, Fe, Ca, As, S, P | Malachite | Low levels of degradation | 3 |

| ||||||||||||||

| Group | Description | Region/Historical Period | Year of Conservation | Pre-treatment | Application of Coating | Arbitrary grading | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Chemical | Stabilization | Coating Thickness (μm) | Coating Layers | Incralac Solvent | Incralac Concentration (%) | Matting Agent | Distributor | FTIR Results | Degradation Grading2 | ||||

| A | Coin | Byzantine | 2002 | Yes | No | BTA | 1.5 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | Second layer, only | D | Very low levels of degradation | 1 |

| B | Coin | Greek Imperial | 1997 | Yes | No | BTA | 2 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | Yes | C | Low levels of degradation | 2 |

| C | Coin | Hellenistic | 1992 | Yes | Yes | Noi | 2 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | Yes | E | Significant degradation mainly due to oxidation | 5 |

| D | Coin | Ancient Greek and Greek Imperial | 1987 | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | Yes | E | Low levels of degradation | 2 |

| E | Coin | Late Roman and Byzantine | 1982 | Yes | No | ? | 3 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | No | E | Very low levels of degradation | 1 |

| A | Coin | Byzantine | 2002 | Yes | No | BTA | 1.5 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | Second layer, only | D | Very low levels of degradation | 1 |

| A | Coin | Byzantine | 2002 | Yes | No | BTA | 1.5 | 2 | Toluene | 10–15 | Second layer, only | D | Very low levels of degradation | 1 |

Objects from the Epigraphic and Numismatic Museum, Athens: Selected coins originating from several archaeological periods and categorized according to their conservation treatments (between 1982 and 2002) were investigated (fig. 37.5; table 37.3–4). They were categorized as follows: Byzantine (group A, conserved 2002), Greek Imperial (group B, conserved 1997), Hellenistic (group C, conserved 1992), Ancient Greek and Greek Imperial (group D, conserved 1987), and Late Roman and Byzantine coins (group E, conserved 1982). It was not possible in every case to detach powdered samples from the coin surface for analysis. Therefore, the analysis was only based on FTIR spectra of the extracted coating using the method described in the Experimental Section. In all cases, little or no BTA was detected, while minor amounts of ESO were found through the epoxy-ring absorption at 1265–1270 –1 absorption (fig. 37.6). Moreover, in this case, too, oxidative degradation of the coating materials was evidenced through the 1642 cm–1 absorption due to oxidation-induced unsaturation, that is, formation of C=C; this was found to be more intense in the case of Hellenistic coins (group C) conserved during 1992 using Incralac acquired from distributor E. From the data in table 37.4, it can be inferred that the poor performance of the coating can be attributed to lack of stabilization of coin surfaces (with BTA) after chemical cleaning as well as possible surface morphology issues such as pitting and cracks in the specific object.

Conclusions

Scrutiny of the conservation records, visual inspection, SEM-EDX analysis, and FTIR analysis of the studied objects resulted in a comprehensive assessment of the condition of the objects’ surfaces, including their coatings. The results from the National Archaeological Museum are listed in table 37.3, while those of the Epigraphic and Numismatic Museum are in table 37.4. It can be seen that in specific cases from both museums, a combination of factors—the product purchased from distributor E, the application method in combination with the treatment practice (i.e., mechanical treatment and stabilization of bronze surface or chemical treatment), and the preservation state of the objects—resulted in poor coating condition. FTIR spectra of extracted coating material in these cases showed oxidative degradation, which resulted in deeply yellowed coating (as evidenced by visual inspection). The fact that in other cases the product from the same distributor (E) performed better leads to the conclusion that pre-treatment of bronze surface by immersing the object in BTA solution helped to form a thin protective film of a copper-BTA complex, which improved the coating’s performance.12 However, it has not been shown whether the absence of BTA in the investigated solvent-extracted coatings is responsible for the overall coating performance at any level. At this point, reflection-absorption FTIR spectroscopy performed in situ and non-destructively on the artifacts’ surfaces could yield a more conclusive assessment; in this study, however, this was not possible. The decision to coat or not to coat museum bronze artifacts is left to the conservator, who must decide the best protocol based on the conditions of the museum environment and handling of the objects. Our study tried to highlight that coating changes may occur long-term and may not yet be visible to the naked eye. Since the conclusion of this study, the conservators of the National Epigraphic and Numismatic Museum have decided to discontinue use of any coatings on their coin collection. Conservators from the National Archaeological Museum still use Incralac coatings on their bronzes, and attest to its good performance relative to other types of coatings.

Notes

- Madsen 1971, Scott 2002, Brostoff 2003. ↩

- Erhardt et al. 1984, McNamara et al. 2004. ↩

- Scott 2002, Craine, Severson, and Merritt 1992, Brostoff 2003, McNamara et al. 2004, Bierwagen, Shedlosky, and Stanek 2002. ↩

- Argyropoulos et al. 2008. ↩

- Brostoff 2003, Erhardt et al. 1984, McNamara et al. 2004. ↩

- Scott 2002, 390. ↩

- Brostoff 2003. ↩

- Lazzari and Chiantore 2000. ↩

- Madsen 1971. ↩

- Boyatzis et al. 2012, Gotoh et al. 2000. ↩

- Scott 2002, 390. ↩

- Madsen 1971, Brostoff 2003. ↩

Bibliography

- Argitis et al. 1998

- Argitis, P., S. Boyatzis, I. Raptis, N. Glezos, and M. Hatzakis. 1998. “Post-Exposure Bake Kinetics in Epoxy Novolac-Based Chemically Amplified Resists.” Micro- and Nanopatterning Polymers, ACS Symposium Series, 706, ed. H. Ito, E. Reichmanis, O. Nalamasu, and T. Ueno, 345–57. Washington: ACS Publications.

- Argyropoulos et al. 2008

- Argyropoulos, V., M. Giannoulaki, G. P. Michalakakos, and A. Siatou. 2008. “A Survey of the Types of Corrosion Inhibitors and Protective Coatings Used for the Conservation of Metal Objects from Museum Collections in the Mediterranean Basin.” In Strategies for Saving Our Cultural Heritage: Papers Presented at the International Conference on Conservation Strategies for Saving Indoor Metallic Collections (CSSIM), Cairo 25 February–1 March 2007, ed. V. Argyropoulos, A. Hein, and M. A. Harith, 166–70. Athens: TEI.

- Bierwagen, Shedlosky, and Stanek 2002

- Bierwagen, G. P., T. J. Shedlosky, and K. Stanek. 2002. “Developing and Testing a New Generation of Protective Coatings for Outdoor Bronze Sculpture.” In Proceedings 28: 2002 Athens Conference on Coatings Science and Technology, July 1–5, 2002, Vouliagmeni (Greece), 289–96. Athens: Institute of Materials Science.

- Boyatzis, Ioakimoglou, and Argitis 2002

- Boyatzis, S., E. Ioakimoglou, and P. Argitis. 2002. “UV Exposure and Temperature Effects on Curing Mechanisms in Thin Linseed Oil Films: Spectroscopic and Chromatographic Studies.” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 84(5): 936–49.

- Boyatzis et al. 2012

- Boyatzis, S. C., A. M. Douvas, V. Argyropoulos, A. Siatou, and M. Vlachopoulou. 2012. “Characterization of a Water-Dispersible Metal Protective Coating with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry, and Ellipsometry.” Applied Spectroscopy 66(5): 580–90.

- Brostoff 2003

- Brostoff, B. L. 2003. “Coating Strategies for Protection of Outdoor Bronze Art and Ornamentation.” PhD diss., Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Craine, Severson, and Merritt 1992

- Craine, C., K. Severson, and S. Merritt. 1992. “Prospects for the Long-Term Maintenance of Outdoor Bronze Sculpture: The Shaw Memorial Nine Years after Cleaning and Coating.” In Abstracts, 20th Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Buffalo, NY, June 4–7, 1992, 30. Washington: AIC.

- De la Rie 1992

- De la Rie, E. R. 1992. “Stability and Function of Coatings Used in Conservation.” In Polymers in Conservation, ed. N. S. Allen, M. Edge, and C. V. Horie, 62–81. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Derrick, Stulik, and Landry 1999

- Derrick, M. R., D. Stulik, and J. M. Landry. 1999. Infrared Spectroscopy in Conservation Science. Scientific Tools for Conservation Series. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Erhardt et al. 1984

- Erhardt, D., W. Hopwood, T. Padfield, and F. N. Veloz. 1984. “Durability of Incralac: Examination of a Ten-Year-Old Treatment.” In Preprints, ICOM Committee for Conservation, 7th Triennial Meeting, Copenhagen, 10–14 September, 1984, ed. D. de Froment, 22.1–3. Paris: ICOM.

- Gotoh et al. 2000

- Gotoh, Y., R. Igarashi, Y. Ohkoshi, M. Nagura, K. Akamatsu, and S. Deki. 2000. “Preparation and Structure of Copper Nanoparticle/Poly(acrylic acid) Composite Films.” Journal of Materials Chemistry 10(11): 2548–52.

- Griffiths and de Haseth 2007

- Griffiths, P. E., and J. A. de Haseth. 2007. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Horie 2010

- Horie, C. V. 2010. Materials for Conservation: Organics Consolidants, Adhesives, and Coatings. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ioakimoglou et al. 1999

- Ioakimoglou, E., S. Boyatzis, P. Argitis, A. Fostiridou, K. Papapanagiotou, and N. Yannovits. 1999. “Thin-Film Study on the Oxidation of Linseed Oil in the Presence of Selected Copper Pigments.” Chemistry of Materials 11(8): 2013–22.

- Lazzari and Chiantore 2000

- Lazzari, M., and O. Chiantore. 2000. “Thermal-Ageing of Paraloid Acrylic Protective Polymers.” Polymer 41(17): 6447–55.

- Madsen 1971

- Madsen, H. B. 1971. “Further Remarks on the Use of Benzotriazole for Stabilizing Bronze Objects.” Studies in Conservation 16(30): 122.

- McNamara et al. 2004

- McNamara, C. J., M. Breuker, M. Helms, T. D. Perry, and R. Mitchell. 2004. “Biodeterioration of Incralac Used for the Protection of Bronze Monuments.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 5: 361–64.

- Merklin 2002

- Merklin, G. 2002. “Infrared Spectrometry of Thick Organic Films on Metallic Substrates.” Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy, ed. J. M. Chalmers and P. R. Griffiths. Vol. 2: Sampling Techniques, 1033–43. New York: Wiley.

- Scott 2002

- Scott, D. A. 2002. Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Stuart 2004

- Stuart, B. 2004. Infrared Spectroscopy Fundamentals and Applications. Chichester: Wiley.