Elephant, Germany (possibly Erfurt), about 1375-1400, Salvatorberg Bestiary (text in Latin)

The Wormsley Library, England, Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire, Ms. BM3731, fols. 3v-4

Transcript

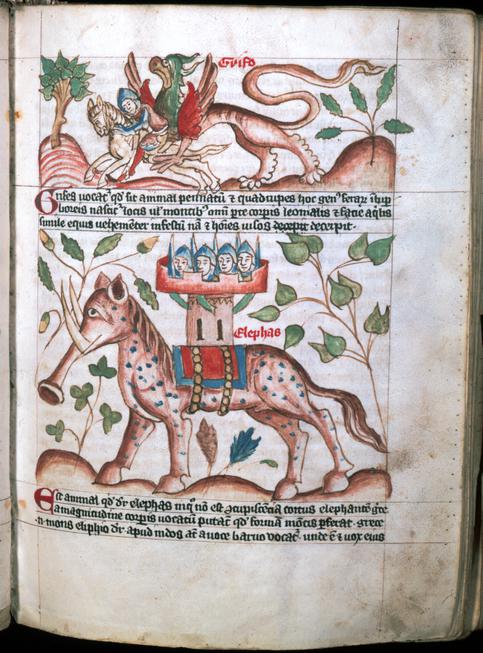

NARRATOR: What a fine medieval elephant we have here. We might think there’s a bit too much creative license taken—with the spots, the trumpet-like trunk, and the small castle holding warriors on its back … But medieval readers knew the basics, even if the overall shape and unlikely details varied across manuscripts. And if you missed the full elephant story before, keep listening.

Few people actually saw a real elephant in the Middle Ages. You couldn’t check the internet or go to a zoo to verify its existence. But you could consult a bestiary to find out all about it.

Elephants were typically depicted as large grey or white beasts with long trunks and straight legs ending in wide, flat feet. Some images were truer to what we now know elephants look like, while others were approximations based on description alone. So they might look like a horse with floppy ears, or a creature whose trunk suggests a trumpet. Often the elephant carries a fortified castle on its back. Fighters could ride in it, waging war against less well-equipped troops.

The elephant conveyed moral messages of kindness toward others, devotion, and spiritual redemption. It was thought that they have no knees and have to sleep propped up against a tree. If the tree breaks, and they fall, a young elephant is the only creature that can raise the toppled elephant to its feet. The young elephant represents Christ, while the rescued adult elephant symbolizes mankind’s redemption from a life of sin.

Elephants were thought to be monogamous. Their sole child is conceived after they visit Paradise and eat from a mandrake tree. Why? Cast as Adam and Eve, elephants reenacted the first sin and subsequent expulsion from the Garden of Eden, as told in the Biblical book of Genesis. To a medieval reader, this tale was a reminder to avoid sin.