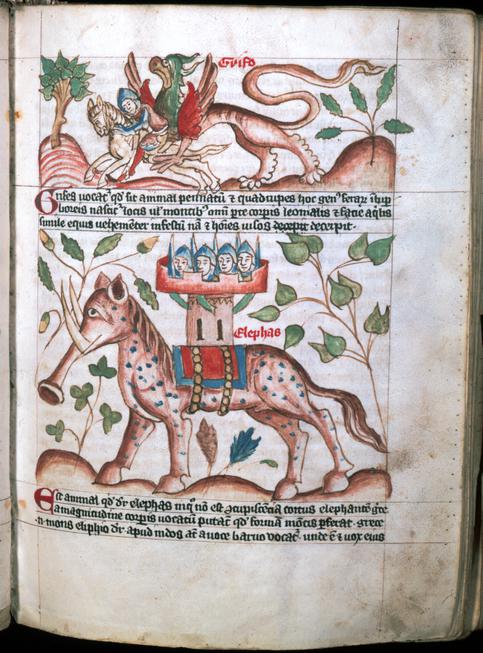

Griffin, Germany (possibly Erfurt), about 1375-1400, Salvatorberg Bestiary (text in Latin)

The Wormsley Library, Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire, Ms. BM3731, fols. 3v-4

Transcript

NARRATOR: What on earth is happening at the top of the manuscript page at right? Well, it’s a man on horseback being seized by a horrific griffin—a man-eating, winged beast with four legs. Back then, people thought that griffins hated horses and would attack them and their unwitting riders, at first sight. If this is news to you, and you’d like to know more, stay on the line...

The griffin is one of those mythical beasts you’d never even want to imagine encountering. The description of its hybrid body parts says it all—an eagle’s head, a lion’s body, wings coated in glossy feathers. It was said that griffins combined the “best” traits of the eagle— “the king of the birds”—and those of the lion—“the king of the beasts.”

Griffins have sharp, powerful claws with which to capture and tear apart humans to feed their young. Claws so strong they can even carry off a live ox. Though terrifying, griffins also had a reputation for being fierce and protective, which is why you see them on many medieval court objects. Griffins appear in church interiors and exteriors and were thought to ward off evil.

In the medieval world, griffins were considered exotic creatures that lived in far-off lands. Their claws and eggs were highly prized for their medicinal value. Supposed griffin claws (usually the horns of real animals such as the ibex) showed up in European church treasuries and court collections, as did griffin eggs (which were typically ostrich eggs). As popular lore would have it, a griffin feather could restore eyesight.

Variations of griffins appeared in many ancient cultures, from the Egyptians to the Persians to the Greeks, among others. Today, you’ll still see them pop up as school mascots.