Buried by Vesuvius

Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri

The Villa dei Papiri was a sumptuous private residence on the Bay of Naples, just outside the Roman town of Herculaneum. Deeply buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, it was rediscovered in 1750 when well diggers chanced upon its remains. Eighteenth-century excavators battled poisonous gases and underground collapses to extract elaborate floors, frescoes, and sculptures—the largest collection of statuary ever recovered from a single classical building. They also found more than one thousand carbonized papyrus book rolls, which gave the villa its modern Italian name. Because many of the scrolls contain the writings of the philosopher and poet Philodemus of Gadara, scholars believe that the villa originally belonged to his patron, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, father-in-law to Julius Caesar.

The ancient villa fascinated oil magnate J. Paul Getty, who decided to replicate it in Malibu, creating the Getty Villa in the early 1970s. Renewed excavations Herculaneum in the 1990s and 2000s revealed additional parts of the building and narrowed the date of its initial construction to around 40 BC. This exhibition presents significant artifacts discovered in the 1750s, explores ongoing attempts to open and read the badly damaged papyri, and displays recent finds from the site for the first time.

Exhibition checklist and gallery texts

Join the curator on a walkthrough of the exhibition in this video.

Rediscovery

The Roman town of Herculaneum was buried under approximately seventy-five feet of volcanic debris from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Artifacts were sporadically unearthed as early as the fifteenth century, but systematic exploration of the ancient city only began in 1738 under the patronage of the Bourbon king Charles VII.

In the spring of 1750, well diggers in the vicinity of the royal palace in nearby Portici struck a stunning circular polychrome marble floor that once decorated the Villa dei Papiri. Shortly afterward, day-to-day responsibility for excavating the site was entrusted to Karl Weber, a Swiss military engineer in the royal guard. Under his direction, a corps of convicts and conscripts dug a series of shafts and tunnels, battling low light, poor air circulation, and noxious fumes to extract precious antiquities from the villa. Although his superiors were chiefly interested in recovering artifacts to enhance the royal collections, Weber carefully recorded the objects’ findspots and architectural contexts. Work was suspended in 1761 for fear of poisonous gases but briefly recommenced in 1763–64. The villa then remained unexplored for more than two centuries until new excavations were undertaken in the 1990s and 2000s.

Epicurus and Philodemus

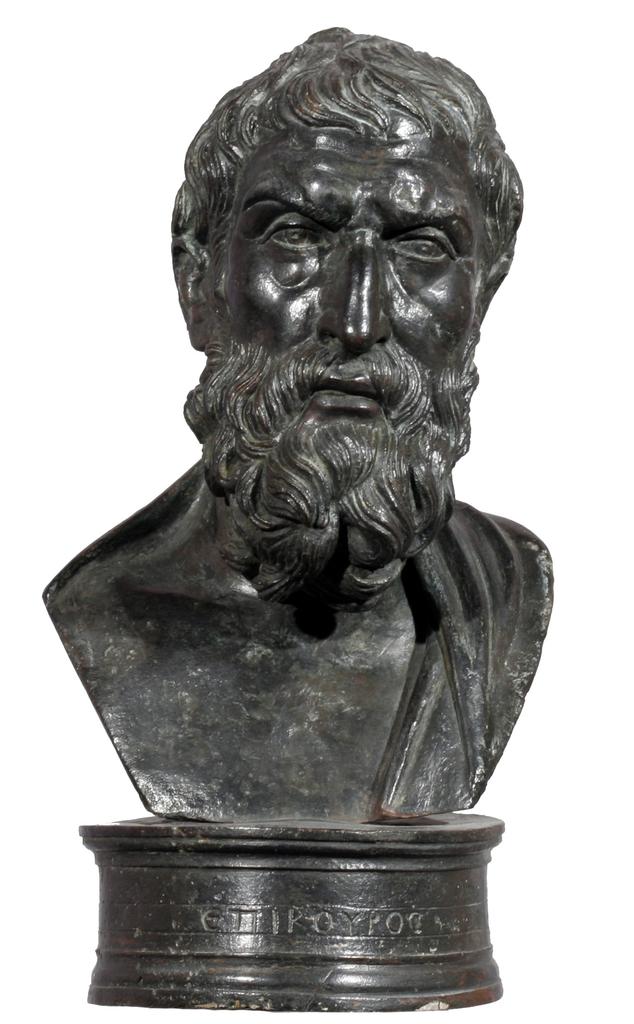

The Athenian philosopher Epicurus (341–270 BC) founded a popular school called the Garden, which recognized pleasure (hedone) as the greatest good. To attain pleasure—defined as a state of tranquility (ataraxia) and freedom from pain (aponia)—he and his followers promoted a life of moderation rather than excess. Epicureans embraced the atomic theories of earlier thinkers, claiming that the material universe is composed of elementary particles subject to constant recombination, causing the eventual and inevitable decay of all matter. They argued that the gods, if they existed, had no interest in the lives of humans and that death was nothing to fear.

Philodemus (about 110–30 BC), born in Gadara (present-day Umm Qais, Jordan), was educated at the Garden in Athens. He later appears to have immigrated to Italy, and his many texts preserved at the Villa dei Papiri are among the most important surviving evidence for Epicurean thought.

The Papyri

The approximately 1,100 papyrus scrolls recovered from the Villa dei Papiri between 1752 and 1754 constitute the only surviving library from the classical world. Although some of the book rolls were neatly stacked on shelves or in cases, early excavators assumed they were logs or carbonized fishing nets. Many were discarded or possibly used as torches. Only when one was dropped and broken, revealing writing within, did their true nature become evident.

Camillo Paderni (about 1715–1781), the first director of the royal museum in Portici, claimed credit for discovering and rescuing the papyri but was also responsible for considerable damage. He sliced the scrolls lengthwise, cutting through their charred outer "bark" to expose the writing. The texts were copied for study and eventual publication, and then the papyri were scraped to reveal additional layers. In 1753 Father Antonio Piaggio, a curator of manuscripts at the Vatican, devised a more successful system. Most of the texts opened to date are Greek philosophical treatises, particularly by Philodemus of Gadara, a follower of Epicurus.

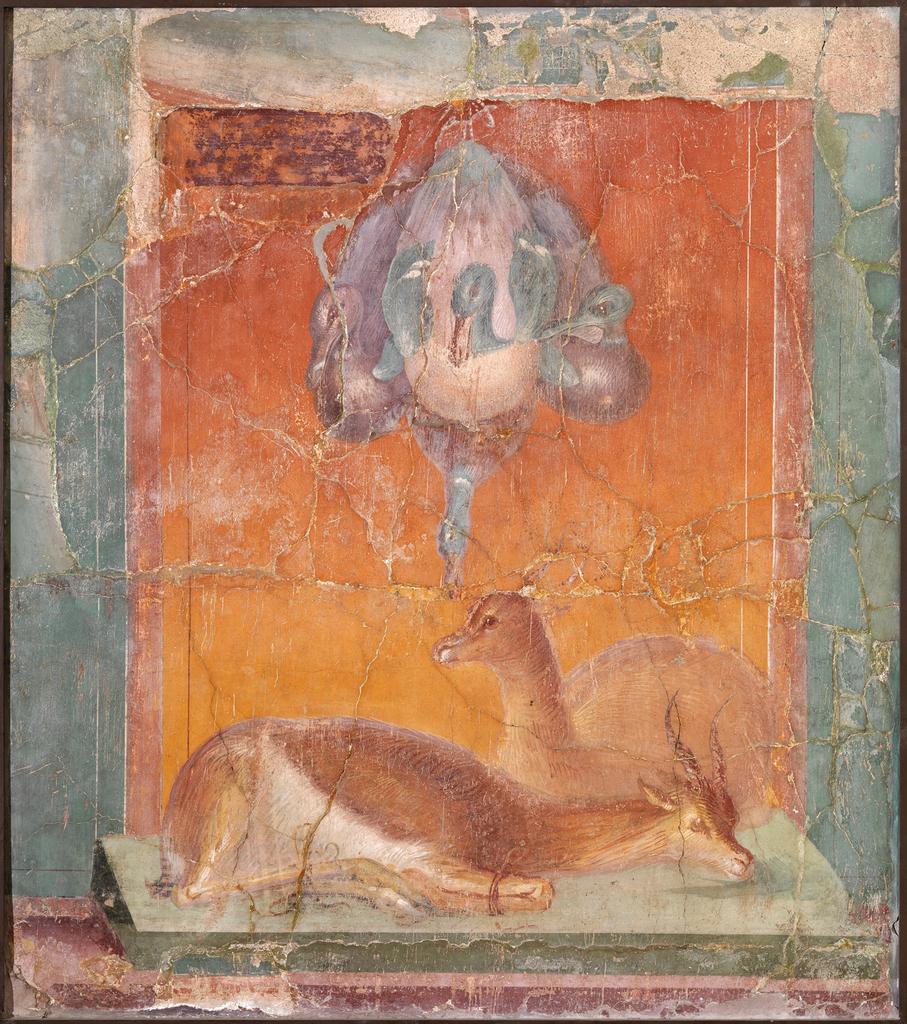

Otium: A Life of Cultured Leisure

For wealthy Romans, otium, or leisure, presented a chance to forget the concerns of city life, to abandon worry about politics or business (negotium), and, according to the Roman author Pliny the Younger, to set aside the need to dress formally in a toga. A seaside estate such as the Villa dei Papiri was the perfect place for an escape of this kind. Its owners could host elaborate banquets where guests were surrounded by art, sating both their gastronomic and their intellectual appetites. They could read poetic and philosophical texts that provided pleasure and stimulated learned debate. Gardens, fountains, and long walkways invited visitors to pause and discuss the sculptures of gods, heroes, famous statesmen, and men of letters that decorated the grounds. Many Roman villa owners styled parts of their luxurious residences after ancient Greek spaces, where they could display their erudition and philhellenism (admiration for Greek culture). Pliny and others considered the pursuit of otium in their villas essential to a more honest and inspirational life.

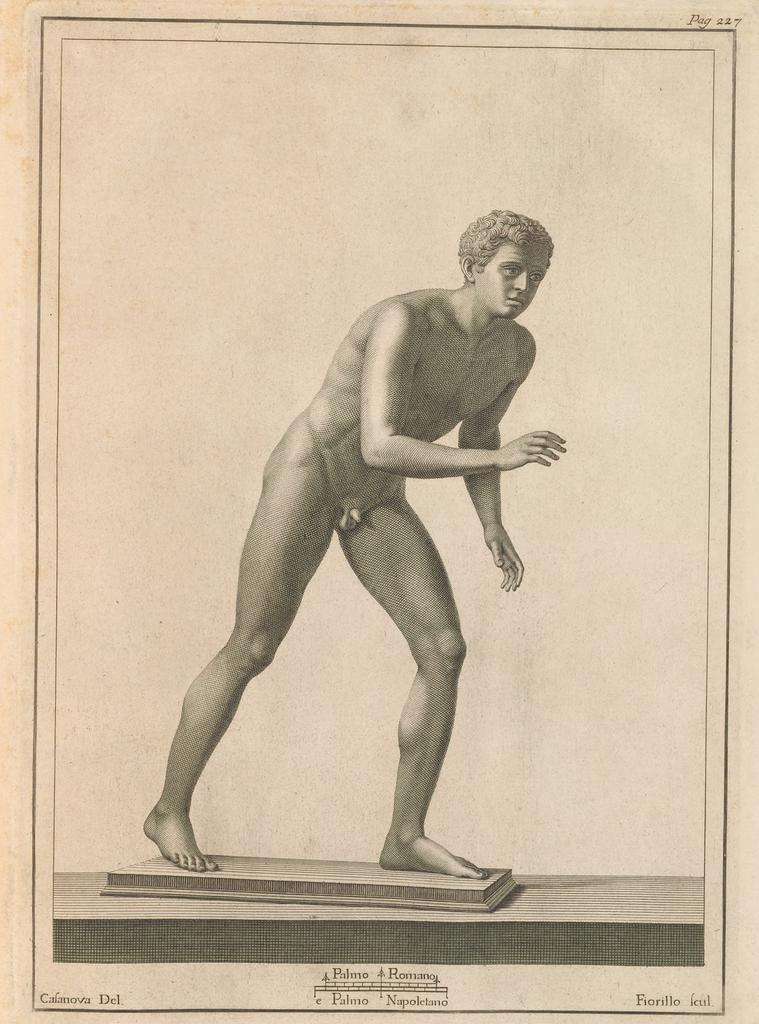

The Antiquities of Herculaneum Exposed

Eight sumptuous volumes containing over six hundred engravings were produced in the series Le antichità di Ercolano esposte (The Antiquities of Herculaneum Exposed), published between 1757 and 1792. Although forty such tomes were planned, only five on paintings, two on bronze sculptures, and one on lamps and candelabra were completed.

This lavish publishing project began in 1755 when King Charles VII engaged fifteen scholars to initiate the Royal Herculanean Academy of Archaeology, dedicated to the study of discoveries from around the Bay of Naples. The king also hired twenty-five artists to make drawings and engravings of the finds. The print run for the series was limited, and the prime minister decided who would receive the coveted volumes. One Neapolitan diplomat complained that the greatest burden of his office was responding to the unending requests for these books.

An Ancient Sculpture Gallery

The rooms and gardens of the Villa dei Papiri were populated by approximately ninety sculptures in bronze and marble. Busts and full-length statues depicted mythological figures, athletes, rulers, statesmen, poets, and philosophers. Several of the sculptures are examples of well-known statue types, and some can be identified by inscriptions preserved on other, similar works. Many of the subjects, however, remain uncertain. Portraits of eminent figures of the Hellenistic period (323–31 BC) seem to predominate, rather than notables of the Classical period (480–323 BC) featured in other ancient collections. This may reflect the villa owners’ interests in Hellenistic philosophy and politics. The arrangement of the sculptures also appears to have been programmatic, presenting particular groupings that invited viewers to compare the accomplishments and failings of the subjects as well as the artistic styles of the works. Of course, visitors would not have taken in all the statuary at once, and alternate routes through the villa would have engendered different experiences.

The Pan Group and Nearby Sculptures

The marble sculpture of the woodland god Pan having sex with a she-goat was discovered in the Villa dei Papiri in 1752. It immediately became notorious and was long off-limits, viewable only in the vaults of the royal palace at Portici by special permission of the king. Its subject matter, objectionable to many, was often contrasted with its refined carving.

Explicit imagery was common in antiquity, and Roman art and literature make frequent references to sexual pursuit and conquest. Some modern commentators have interpreted this sculpture as evidence of the Romans’ reverence for the generative power of sex. Others have seen it as a satire on the bestial nature of all men.

As many of the sculptures in the villa seem to have been grouped thematically, it is tempting to link this work with three busts found nearby. The Macedonian king Demetrios Poliorketes is depicted with horns, like Pan, and was famously dissolute. Another bust represents the Greek poet Panyassis of Halikarnassos. Could these works have been part of an ancient display punning on Pan?

New Discoveries

Exploration of the Villa dei Papiri was abandoned in 1764. Its tunnels were backfilled and its precise location underground was forgotten despite the ever-growing fame of its contents. Renewed interest in the site in the 1980s led to limited excavations in the 1990s and 2000s, which brought to light a portion of the building’s atrium as well as lower levels that were unknown in the eighteenth century. Among the new discoveries were rooms with colorful mosaic floors and spectacular frescoed walls and stuccoed ceilings. Finds also included a seaside pavilion and swimming pool, where archaeologists recovered two marble sculptures and luxurious wood and ivory furniture components. These recent excavations helped clarify the chronology of the villa, which is now thought to have been built around 40 BC, with the seaside pavilion added around AD 20. Ongoing research continues to advance our understanding of the initial finds from the site.

The Getty Villa and the Villa dei Papiri

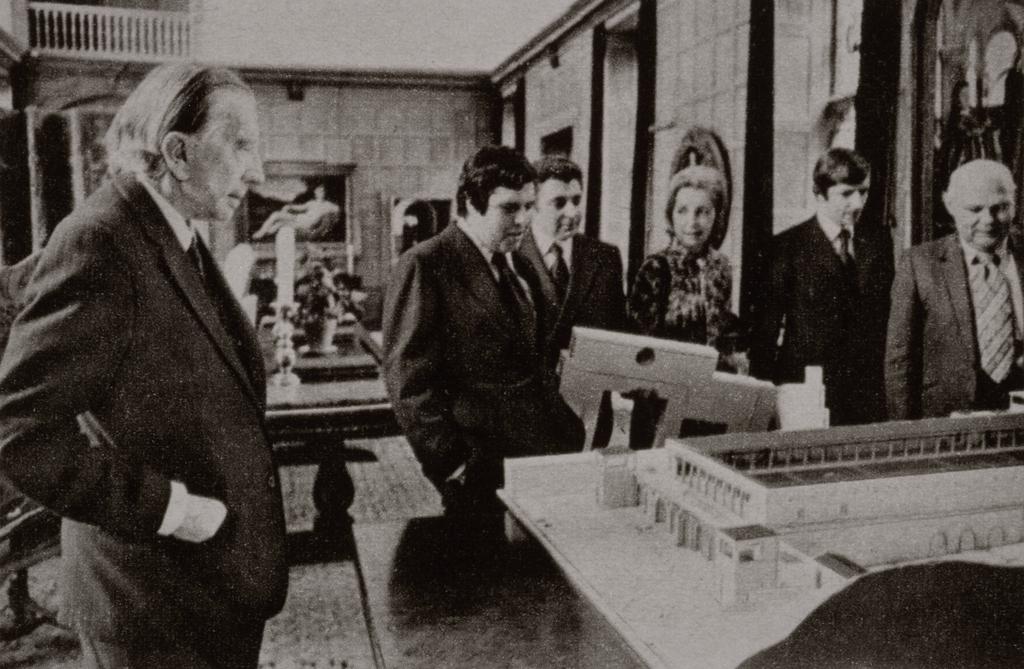

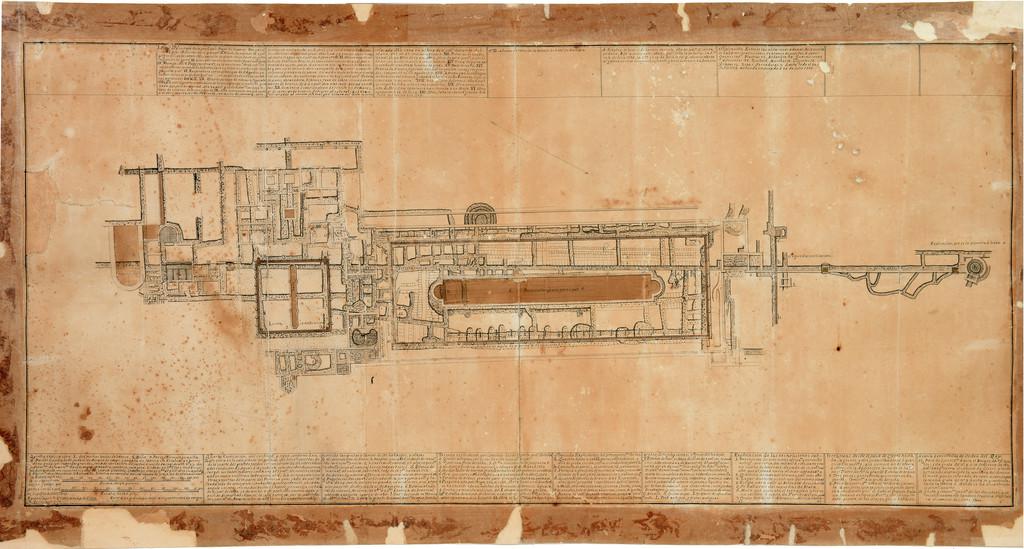

J. Paul Getty began acquiring art in the 1930s, and by the late 1960s his collection had outgrown his Spanish-style ranch house in Malibu. He decided to build a new museum as a replica of the Villa dei Papiri, deeming it an appropriate setting for his Greek and Roman antiquities. Because the original building at Herculaneum was inaccessible underground, Getty’s architects relied on Karl Weber’s eighteenth-century plan and employed elements from other ancient structures discovered around the Bay of Naples.

Re-creating the Villa dei Papiri appealed to Getty because of its association with Julius Caesar through his father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the villa’s supposed owner. Getty often compared himself to ancient Roman rulers, writing in his autobiography, "I feel no qualms or reticence about likening the Getty Oil Company to an 'Empire'—and myself to a Caesar" (As I See It, 1976). He also fancied himself the reincarnation of the emperor Hadrian, a fellow art collector and villa owner. Although Getty, unlike Hadrian, did not live in his villa, his reconstruction was a key component in his attempts to refashion himself from a Midwestern businessman into a European aristocrat.

English Translation of the Legend of Karl Weber's Excavation Plan of the Villa Dei Papiri