Cy Twombly

Making Past Present

Cy Twombly (1928–2011) ranks among the most prominent US painters to emerge in the 1950s, a period of radical experimentation in American and European art. Combining gestural strokes of paint, broad areas of empty space, and words scribbled in a nearly illegible hand, Twombly’s work can be enigmatic, even perplexing. Making sense of it requires an appreciation of his attitudes toward history, place, and cultural memory.

This exhibition explores Twombly’s art through the lens of ancient Greek and Roman culture, a consistent source of inspiration throughout his career. Twombly avoided centers of modern art like New York, moving to Italy in 1959. There he engaged creatively with the enduring legacy of antiquity, infusing his work with provocative allusions to mythology, poetry, and archaeology. By exploring the classical past, Twombly followed a long tradition in American and European art. His great contribution lay in linking his understanding of ancient art and literature to late-twentieth-century modernist practice, translating historically remote references into a bracingly contemporary artistic idiom.

This exhibition is organized with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Inspirations

Twombly’s engagement with Greek and Roman antiquity was rich and various. He was a reader of ancient texts and a student of mythology, poetry, and philosophy. A frequent traveler and expatriate, he sought out and lived among centuries-old sites, monuments, and artifacts. As an artist, he followed in the footsteps of famous predecessors whose creative dialogues with antiquity conditioned his own. Twombly was intent on marking his place in this tradition, but he did so in an artistic language that was unmistakably contemporary. While aiming to reinvigorate the distant past, his work implicitly acknowledges the huge gulfs of language, culture, and history that separated him from it.

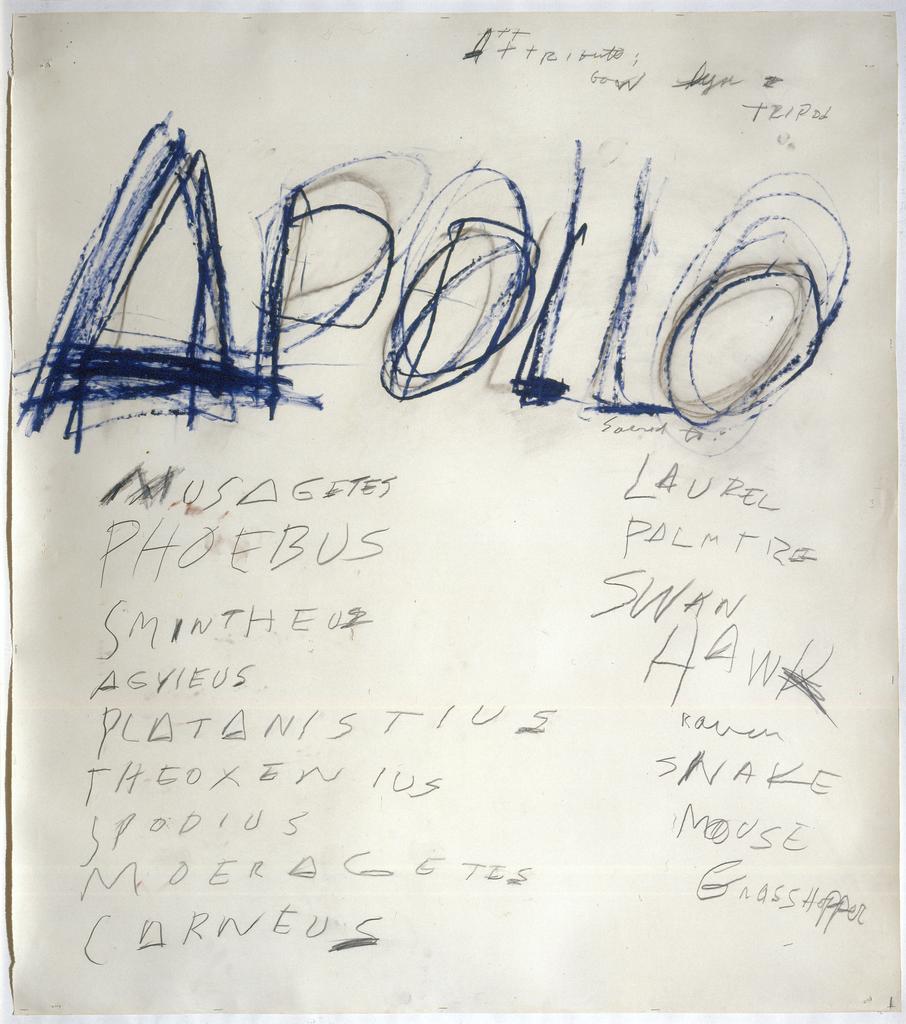

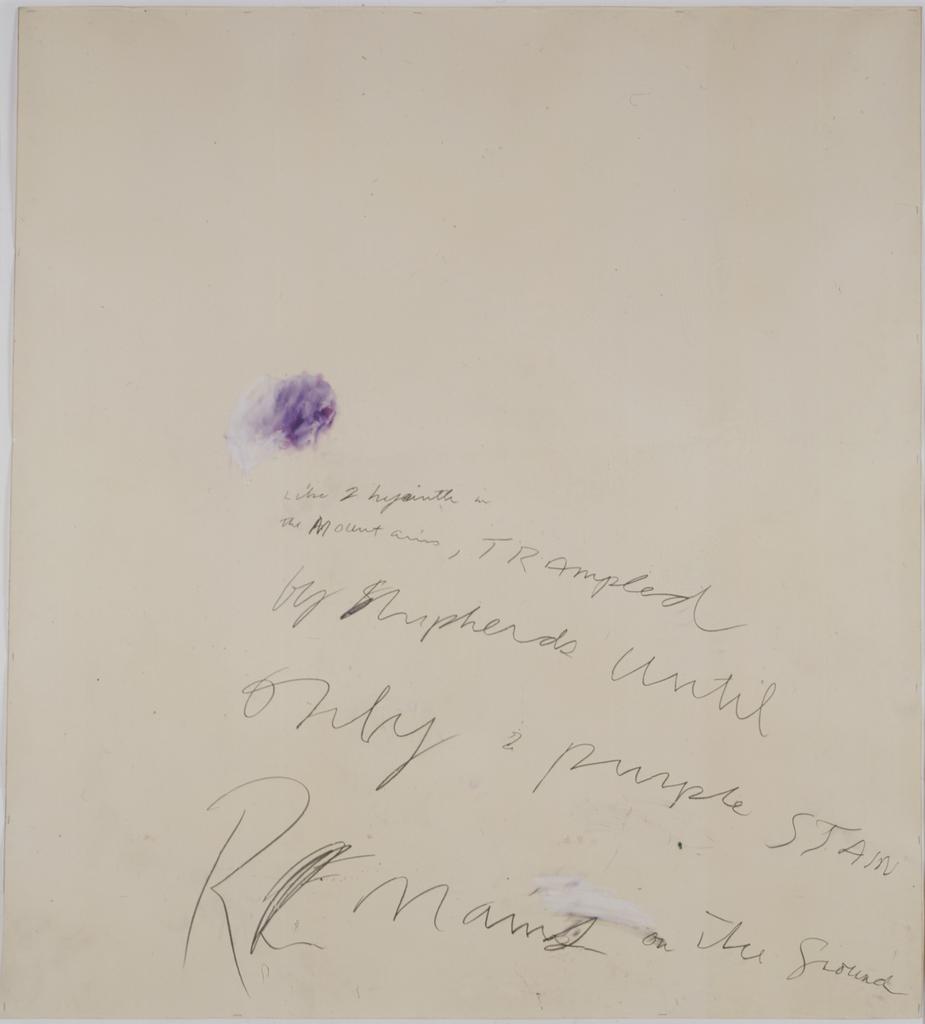

Poetry

Twombly loved ancient Greek and Latin poetry. Reading it (always in English translation) became part of his creative process, and starting in the 1960s he incorporated poets’ names and verse into his work. His was no straightforward literary transcription, however; he leaves us to puzzle over the relationship between free-floating snippets of poems and an abstract vocabulary of graphic scrawls and painterly blotches.

Drifting in and out of legibility, Twombly’s work comes across as elusive, private, and coded, but it also invites the viewer to engage freely and imaginatively, to search for meaning among the scattered signs and gestures. And the temptation is strong, because the world evoked in fragmentary lines by early lyric poets such as Sappho and Archilochos is not coldly remote but alive with urgent passions and desires. It might even be said that this poetic world of the ancients gave Twombly the space to express his own fluid sexuality, however indirectly and ambiguously.

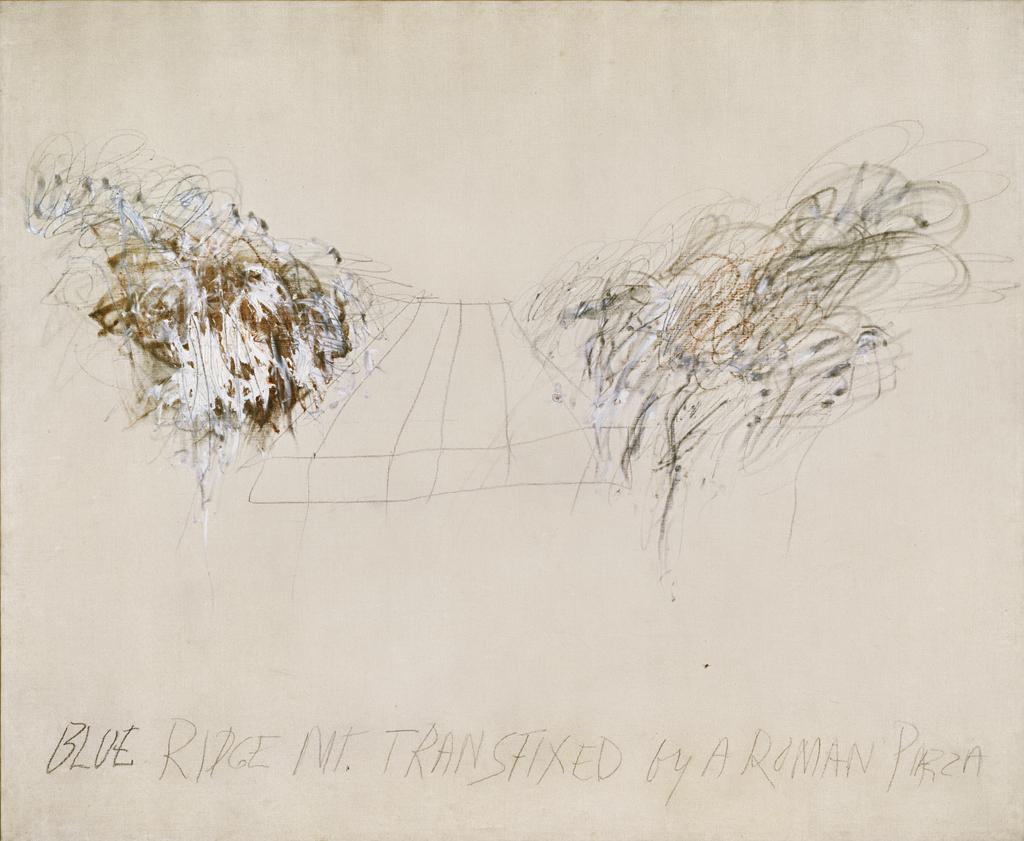

At Home Abroad

Twombly traveled throughout his life, not only in Italy but across Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and central Asia. While he continued to spend months at a time in the United States, in 1959 Italy became his primary residence. He lived first in an apartment in Rome, then moved in 1975 to a sixteenth-century villa at Bassano in Teverina, in northern Italy; from 1994 on, he resided in a villa in Gaeta, on the coast between Rome and Naples.

Travel inspired Twombly’s art, but so did his domestic environments, which were themselves often historical spaces where he lived casually alongside his own work and the antiquities that he passionately collected. His paintings were sometimes described as “rooms,” which viewers could metaphorically enter, while the actual rooms he inhabited call to mind his paintings: whitewashed, spare yet dynamic, replete with references to worlds old and new.

"Roman Classic Surprise"

In 1966 the photographer Horst P. Horst portrayed Twombly, as well as his wife Tatiana Franchetti and son Alessandro, in their Rome apartment for a profile in Vogue magazine, titled “Roman Classic Surprise”. The photos highlighted the artist’s habit of displaying ancient sculptures together with antique furniture, his own art, and the works of his contemporaries, including Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Claes Oldenburg. According to the article, “The apartment is indescribable in terms of decoration, if only because its contents are involved in a continuous process of removal and replacement.” Annabelle d’Huart, who later photographed Twombly’s homes in Rome and Bassano, noted that the “entire environment was exactly like a Twombly painting.”

Sound

Words—names, phrases, excerpts of poetry— form a primary element of Twombly’s work. He once said, “I like poets because I can find a condensed phrase . . . the essence of something.” The graphic notations that abound in his paintings and drawings invite viewers to read aloud and listen as well as to look, making engagement with Twombly’s art a multisensory experience.

In 1951 Twombly met the American modernist poet Charles Olson, who practiced breath-based poetics and sought spontaneity in his writing. For this effect he took the syllable, not the word, as the unit of creation, and he found “breath” in the spacing and page layouts and in the breaking up of a sensible flow of narrative. Just as Olson’s poetry has a strong visual aspect incorporating spaces (silences) and disjunctions, so too does Twombly’s art employ white paint, fragmentation, gaps, sparse surfaces, and erasures.

Love

Throughout his career Twombly was drawn to Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans), the goddess of desire and love. His preoccupation came in part from his dedicated readings of translations from the early Greek poets, especially Sappho, who often evoked the deity as both a muse and a tyrant. Twombly broke with the long tradition of representing Aphrodite as the embodiment of ideal female beauty. He preferred to reference her through words—her various names as well as the places where she was worshipped—or through abstract gestures and shapes like trapezoids and rectangles that were perhaps stand-ins for ancient sculptures. While Twombly’s scrawls and layers of mark making and erasure can seem enigmatic, his works devoted to Aphrodite/Venus reveal a visceral sensuality, luring the viewer into his vision of desire, passion, and the violence that forever accompanies the goddess.

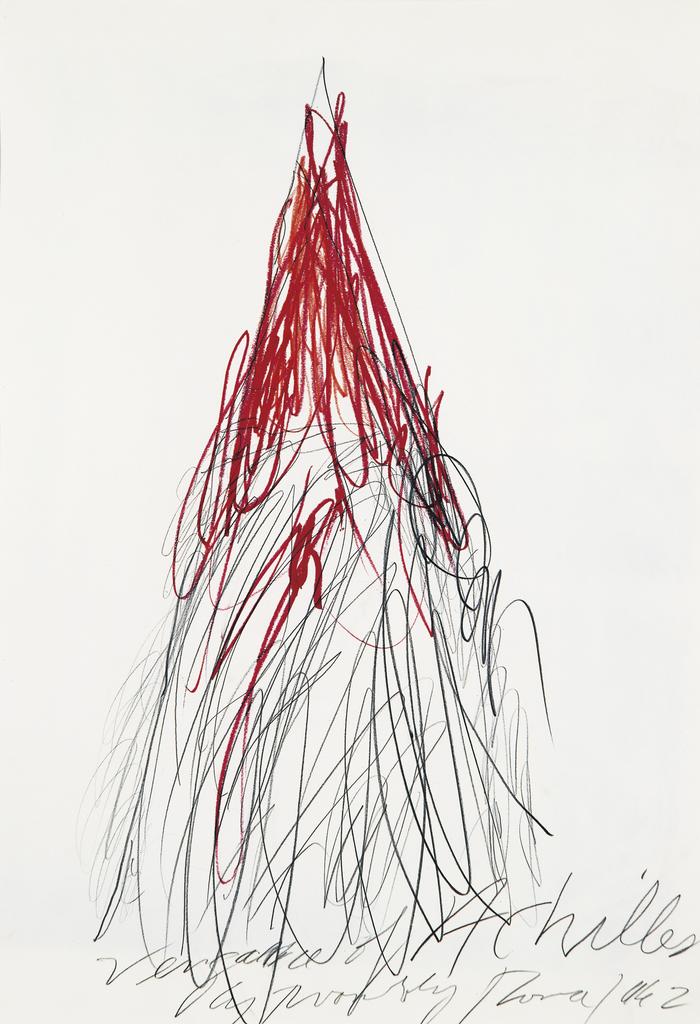

War

The works Twombly dedicated to the war god Mars are thematic counterparts to those he devoted to Venus. Considered together, they raise fundamental questions about the relation between sex and violence, femininity and masculinity, creation and destruction. The selection displayed here refers to murderous power struggles, legendary warriors, and famous battles in ancient history and myth—and resonates with the ancient armor that the artist collected. Twombly’s touchstones were classics like Homer’s epic the Iliad, but he subversively reimagined them, translating their violence through his chaotic, libidinal mark making; the field of painting itself becomes a figurative battlefield. While engaging with the distant past, Twombly’s art pointedly addressed his historical moment, which was marred by political assassinations and the Vietnam War.

In Memoriam

An elegiac strain runs through Twombly’s art, and many works dwell on mortality, transience, time, and memory. His sculptures in particular evoke ancient tomb structures, burial mounds, gravestones, and statue pedestals, yet their small scale, rough construction, humble materials, and lack of site specificity make them as much anti-monuments as monuments. They raise complex questions about the act of memorialization and prompt us to reflect on the possibilities of communicating across time. If much of Twombly’s art is about revitalizing the ancients, about “making past present,” it also confronts the inevitability of present becoming past, with all the effacement, loss, and absence that implies.