|

The Statue of a God arrived at the Getty Villa for conservation in over 150 pieces. Many of its restoration parts, well preserved in Dresden after their removal from the figure in the 1800s, traveled with it so that they could be conserved and documented as well.

Disassembly and Cleaning

As the first step, conservators disassembled and cleaned all the statue's fragments.

Conservators removed plaster, resin, and lead and iron pins that had been used in previous restorations to hold pieces together. Since these restoration materials can become discolored and damaging with age—resins yellow and metals corrode—they were all removed to preserve the ancient marble. De-restoration also revealed what survived of the original work and what dated to a later period.

|

|

Large parts of the statue's torso and base in the Antiquities Conservation studio at the Getty Villa at the beginning of the restoration work in 2007.

|

|

All parts of the statue were inventoried and cleaned before reassembly began.

|

|

|

As the fragments were being cleaned and old plaster was removed, the statue's ancient construction was fully revealed. The statue was fashioned from two blocks of marble, joined together by a large tenon and mortise carved in the figure's midsection. The drapery around the hips artfully concealed the seam between the two stone sections. Other classical sculptures were constructed using such a technique, but a join of this size is rare.

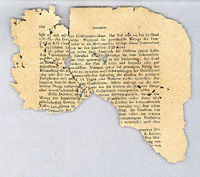

During disassembly and cleaning, conservators also found scraps of paper from a German medical volume on delirium tremens stuffed into two holes—one in the stump of the right arm, the other in the right side of the torso. The holes resulted from the removal of the plaster arm added by Emil Cauer in 1830, and the paper had been inserted to limit the amount of plaster required to fill them. Printed in 1884, the torn page indicates that this phase of restoration was carried out under Georg Treu, director of the Skulpturensammlung in Dresden from 1882 to 1915. Determining the type of plaster used at this point helped conservators understand the sequence of restorations that the statue has undergone since the 17th century.

|

|

Cleaning and disassembly revealed the statue's ancient construction: a carved tenon (the projecting member below) was inserted into a mortise (the cavity above) to join the statue's two halves together.

|

|

This fragmentary page from the 1884 book Delirium Tremens und Delirium Traumaticum was found in two holes in the sculpture during restoration.

|

|

|

Reassembly and Reidentification

Conservators from the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden worked together to reassemble the statue. They used reversible techniques and stable materials (such as stainless-steel pins rather than iron) that will not harm the marble and will make disassembly easier in the future. Fragments were joined into the two larger sections from which the figure was originally constructed, and these were then fitted together.

A workshop was held in Malibu in June 2008 to discuss the sculpture's final determination. Getty and Dresden curators and conservators reviewed the past additions and identities. They felt that the restored ancient core was quite beautiful and needed no further enhancement. Because the original head is lost, it will never be known if the figure is Bacchus or Antinous in the guise of the god. The decision was made not to add any of the former heads or right arms, and to call the statue Bacchus.

|

All images on this page: Statue of a God, Roman, A.D. 100–200, marble, 80 in. high. Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden |