Persia

Ancient Iran and the Classical World

Ancient Iran, historically known as Persia, was the dominant nation of western Asia for over twelve centuries, with three successive native dynasties—the Achaemenid, the Parthian, and the Sasanian—controlling an empire of unprecedented size and complexity. This exhibition, the latest in the Getty Museum’s program The Classical World in Context, explores ancient Iran’s far-reaching exchanges with Greece and Rome. The works on view are vivid expressions of political and cultural identity, showing how these superpowers each constructed their self-image and profoundly influenced that of their rivals.

The Greeks first came into conflict with the Achaemenid Persians in 547 BC, when Cyrus the Great captured western Asia Minor (in present-day Turkey) and subjugated the Greek cities there. Mainland Greece, too, struggled against expanding Achaemenid rule but emerged victorious from a series of invasions in the early fifth century BC. In 334–330 BC, in response to many years of hostilities and the continuing Persian domination of the Greek cities in Asia Minor, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great led his army into Asia and conquered the Achaemenid Empire, establishing Greek control over the region for more than two centuries. During the second century BC, however, the Parthians reclaimed the lands lost to the Greeks, and by the beginning of the first century BC, the Romans replaced the Greeks as the major force in the Mediterranean, becoming the new rival to Persia. In AD 224 the Parthians were overthrown by another Iranian dynasty, the Sasanians, who inflicted many defeats on the Romans before restoring a balance of power that endured until the Arab conquest in in AD 651.

The Achaemenid Empire and the Greeks (550-330 BC)

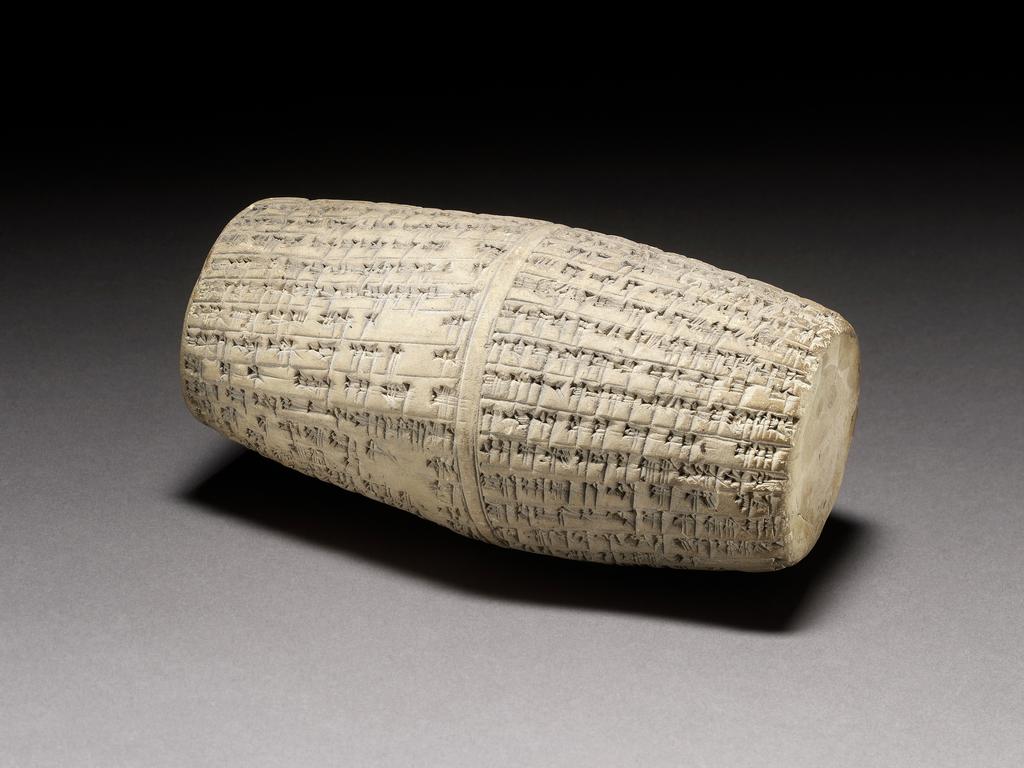

The Persian king Cyrus II, “the Great” (ruled 559–530 BC), renowned by the ancient Greeks and Iranians alike as an illustrious conqueror and skillful ruler, created the largest and most powerful empire of antiquity. In swift succession he captured Media, the dominant kingdom of Iran; then Lydia, which controlled Asia Minor (present-day Turkey); and finally Babylon, from which he inherited authority over most of the Near East. Cyrus’s son Cambyses II (ruled 530–522 BC) added Egypt to Persian territory, and under Darius I, "the Great" (ruled 522–486 BC), the Achaemenid Empire—named for his ancestor Achaemenes—reached the height of its power, claiming allegiance from more than twenty nations stretching from northern Greece to the borders of India. These lands were administered as semiautonomous provinces, whose individual religions and traditions were respected as long as tribute was paid to the king. Darius drew on this mixture of diverse cultures to fashion the distinctive court style seen in the art and architecture of his grand capitals at Susa and Persepolis.

The Greek cities long established on the western coast of Asia Minor resisted Persian demands for submission. A revolt there in 499–494 BC was followed by Persian invasions of the Greek mainland in 492, 490, and 480–479 BC. Against the odds, the combined armies of Athens, Sparta, and their allies were able to defeat the much-larger Persian forces, and pride in these victories became an integral part of Greek self-identity. Although hostilities between Greeks and Persians in Asia Minor continued for much of the fifth century BC, Greeks were highly valued as soldiers, doctors, and artists in the service of the Persian king and his satraps (provincial governors).

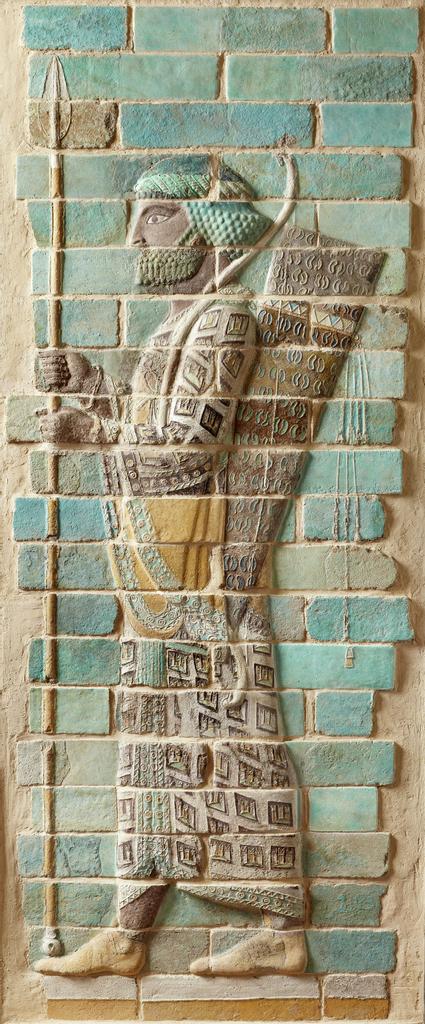

Susa

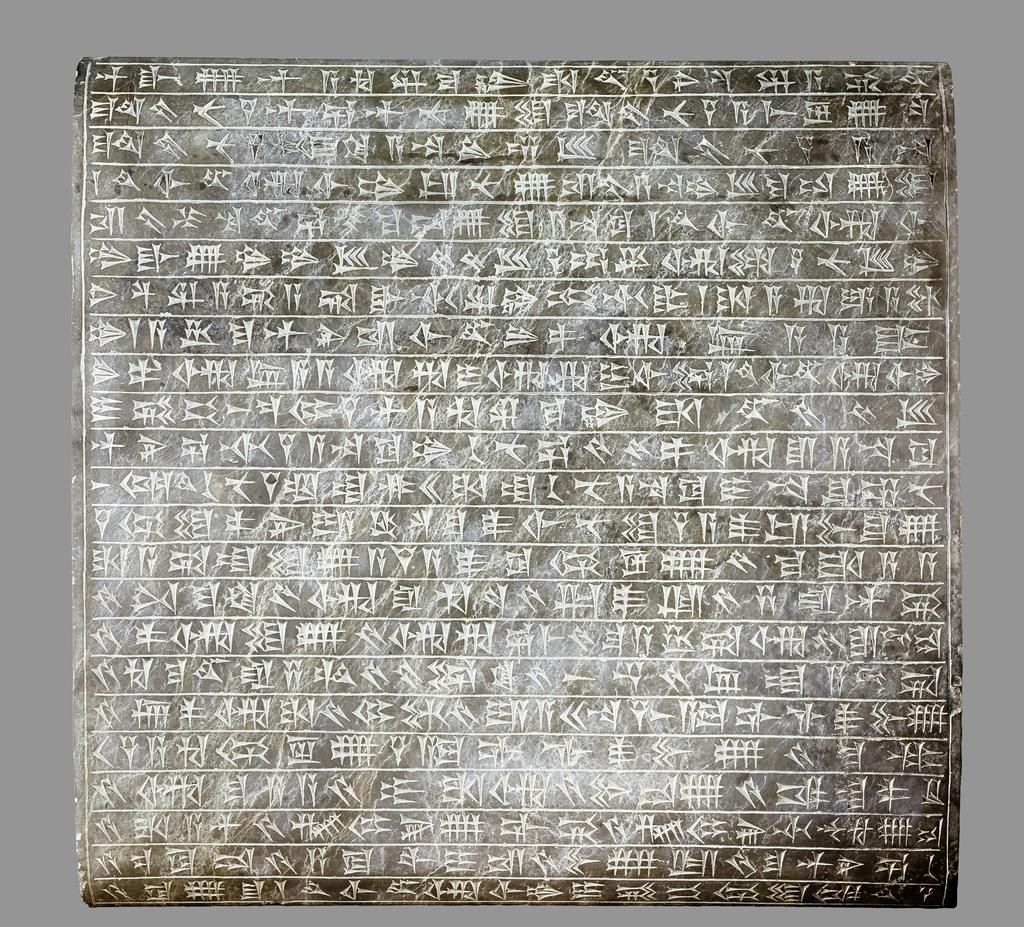

The Achaemenid king Darius I (ruled 522–486 BC) erected a palace complex at Susa (in southwestern Iran), the ancient capital of the Elamites, who had inhabited the region for over two thousand years before becoming vassals of the Persians. As at Darius’s imperial capital of Persepolis, the palace decoration at Susa synthesized traditions and techniques from every part of the empire, reflecting its scope and cultural diversity. A trilingual inscription found there lists the rare materials and specialist craftsmen brought from all the subject nations to create the complex. Although the architecture is poorly preserved today, colorful glazed-brick wall panels survive, depicting lion-griffins, royal sphinxes, and rows of palace guards. They were made by skilled artisans from Babylonia (in present-day Iraq), where there had been a long history of working in this medium, but the images themselves are in the new Achaemenid court style.

Persepolis

Around 518 BC Darius I began to build a new capital, Persepolis (also known as Takht-e Jamshid, in southwestern Iran), which would serve as the ceremonial and courtly center of the Achaemenid Empire. Darius and his successors constructed magnificent palaces, treasuries, and a large audience hall (Apadana) on an enormous terraced platform intended to convey a sense of grandeur and awe. Brightly painted relief sculptures showed the Persian monarch surrounded by his guards and courtiers while receiving delegations of subject peoples bearing tribute—Medes, Elamites, Babylonians, Lydians, Egyptians, and Greeks, among many others. This carefully planned composition glorified the king as ruler of a vast multiethnic empire under the protection of his patron deity, Ahura Mazda.

Achaemenid Luxury Metalwork

The Achaemenid Persian kings drank from ornate gold and silver vessels at their banquets. These valuable objects also served as symbols of power and status, brought to the king as tribute and presented by him as gifts to his loyal courtiers. A distinctive court style was created during the reign of Darius I, with vessels of characteristic shape that included drinking horns and wine jars (called rhyta and amphorae in Greek) decorated with figures of mythical beasts. Shallow cups and bowls (phialai) were the drinking vessel of choice, typically ornamented with embossed lobes and stylized floral patterns.

Gems and Coins from the Western Achaemenid Empire

Personal seals carved from semiprecious stones were used widely within the Achaemenid Empire, impressed into clay as a form of signature. Those produced in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey) display a hybrid Greco-Persian style and typically depict images popular with the Achaemenid aristocracy, including scenes of warfare and hunting.

Coinage was invented by the Lydians in the late seventh century BC and was soon adopted by the Greeks in the region. Although coins did not circulate widely in Achaemenid Iran, they continued to be minted in Asia Minor under the Persian authorities, alongside issues by Carian, Lycian, and Greek cities there. Just before 500 BC, the Persians introduced a new gold coin bearing the image of the king, which the Greeks called a daric after Darius I. Other Achaemenid coins bear portraits of the satraps who governed the various provinces of the empire.

Athenian Pottery

A number of Athenian vases reflect the sense of pride and relief felt by the Greeks after their victories over the tremendous power of the Achaemenid Empire in a series of wars during the early fifth century BC. The painted images attest to shifting perceptions and attitudes, ranging from respect to disparagement, hostility to fascination. A number of Athenian vases reflect the sense of pride and relief felt by the Greeks after their victories over the tremendous power of the Achaemenid Empire in a series of wars during the early fifth century BC. The painted images attest to shifting perceptions and attitudes, ranging from respect to disparagement, hostility to fascination. Some depict Greek warriors defeating Persians, who are alternately shown in flight or putting up a strong fight, while others present Persian life and culture as foreign and exotic. Luxury vessels of Persian form, notably animal-headed drinking horns (called rhyta by the Greeks), also had a marked influence on Athenian vase makers.

Greeks, Romans, and Parthians (330 BC–AD 224)

The Macedonian king Alexander III, "the Great," conquered the Achaemenid Empire in a rapid military campaign (334–330 BC), portraying himself as the liberator of the Greeks in Asia Minor and the rightful king of Persia. After his death in 323 BC, his general Seleucus I (ruled 305–281 BC) eventually seized control of Alexander's eastern territories, including Syria, Mesopotamia, and Iran, and established a dynasty that ruled for more than two centuries. The Seleucid kings viewed themselves as the heirs of the Achaemenids and first governed from the ancient centers of power at Babylon and Susa. They founded many new Greek cities throughout the region, and Hellenistic Greek culture made a marked impression on the Iranian and other local nations, which would soon reassert political authority.

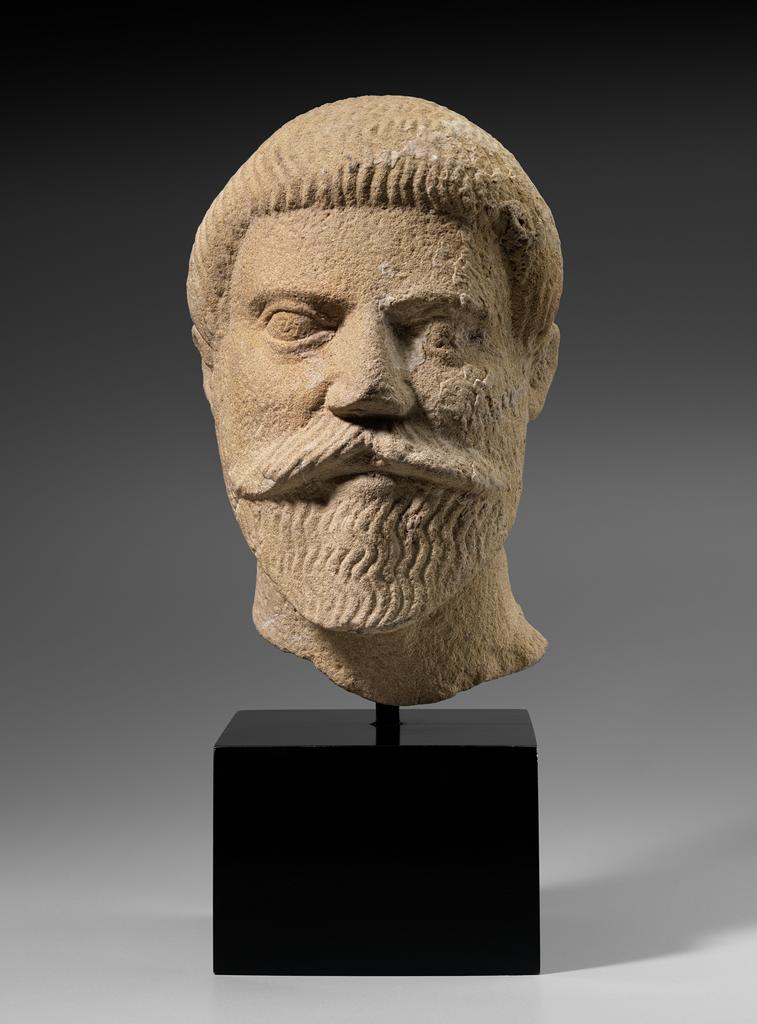

Around 247 BC the Iranian king Arsaces I created an independent state in the region of Parthia, in northeastern Iran. His successors, known as the Arsacids, quickly expanded their territory at the expense of the Seleucids, taking control of all of Iran and much of Mesopotamia by the mid-second century BC. The Parthian Empire became the dominant state of the Near East, ruling over a number of regional kingdoms for nearly five hundred years. It was also the primary rival of Rome, the new superpower in the Mediterranean, with the borderlands of Mesopotamia being a frequent battleground. Parthian art is highly eclectic, displaying a mixture of Greek, Mesopotamian, Achaemenid Persian, and nomadic Iranian influences

Parthian Silver

The Parthian aristocracy used sumptuous silver wine vessels as symbols of status in their ritualized banquets, continuing an Achaemenid Persian courtly practice that had been adopted by the Seleucid Greeks. The rhyton (Greek for “flowing vessel”), an ornate drinking horn terminating in the forepart of a wild animal, had long been traditional in Iran and was especially popular on these occasions. The vessels on view here are stylistically Greek, but inscriptions added to the rims name Parthian owners.

Iran and Roman Religion

A number of new religious cults found converts in the Roman Empire during the first three centuries of imperial rule. One particularly popular religion centered on the worship of the solar deity Mithras, derived from the Iranian god Mithra, whose ceremonies were celebrated by groups of men in elaborate initiation rituals. The Romans understood little of the authentic Iranian tradition and created their own complex mythology, today mostly lost except for the images preserved in the sculpture and paintings that decorated the many Mithraeums (temples to Mithras) from Britain to Syria. In these pictorial representations, the god is typically shown in Persian dress, heroically sacrificing a heavenly bull. The central idea of a creative sacrifice that sustains the cosmos was an Iranian element without parallel in the Greco-Roman world.

The Iranian priests known as Magi had long been viewed by the Greeks and Romans as possessors of ancient knowledge and advisers to the Persian kings. In the biblical Gospel of Matthew, they travel from the East bearing gifts for the infant Jesus, whom they proclaim king of the Jews. In early Christian art, they are shown dressed in trousers and peaked caps to indicate their Eastern origin.

Coins and Ornaments of the Seleucid and Parthian Empires

Beginning with Arsaces I (ruled about 247–217 BC), Parthia’s first king and the founder of the Arsacid dynasty, all the Parthian kings issued coins reflecting their authority. Following the model of Seleucid Greek coinage, Parthian coins always display an image of the ruling monarch on the obverse (front). Although Arsaces I was depicted in the attire of a Persian satrap (provincial governor), Parthian coins were initially Greek in style, bearing Greek inscriptions and often showing the king wearing the diadem of Greek monarchs. Over time, however, they lost their Greek appearance and became highly stylized, with barely legible inscriptions, manifesting a political intent to express a more distinctively Iranian identity.

The Parthians grew wealthy through lucrative trade networks and produced luxurious jewelry inlaid with semiprecious stones. The use of garnets followed Greek fashion, while turquoise was popular in Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia.

Texts from the Seleucid and Parthian Empires

Both the Seleucid and the Parthian kings faced the challenge of ruling a large territory in which many languages were used for a variety of purposes. Beyond the heartland cities of Persepolis and Susa (where Elamite was widely in use), Aramaic had been the principal bureaucratic language of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and it was still sometimes employed under the new Greek rulers. Greek language and institutions, which were introduced to the region by the Seleucids, survived under the Parthians. In the ancient temples of Mesopotamia, priests continued to write in the Babylonian and Sumerian languages. The numerous clay tablets found in temple archives, especially at Babylon and Uruk, include many mathematical and scientific texts, astronomical observations, and royal decrees and dedications.

The Sasanain Empire and the Romans (AD 224–651)

In AD 224 the Parthian Empire was overthrown by Ardashir I, king of Persis (in southwestern Iran), the historical heartland of the Persians. Ardashir established the Sasanian dynasty, named for his ancestor Sasan, which would rule Ērānshahr—"the empire of the Iranians”—for over four centuries. The Sasanians created a new Iranian self-image with distinctive trappings of kingship and splendid royal art, a more centralized administration, the founding of many cities, and an aggressive military policy. Ardashir’s son Shapur I achieved a series of victories over the Romans, culminating in the capture of Emperor Valerian himself in AD 260. The Roman Empire soon revived and, with the conversion to Christianity in the fourth century, moved its capital east to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey), where it later became known as the Byzantine Empire. Despite near constant warfare, the two great empires recognized the advantages of maintaining a balance of power and were often allied in fighting mutual enemies. The rise of the Arabs under the banner of Islam, however, brought an end to the Sasanian Empire in AD 651.

Displays of power and propaganda produced by the royal courts in Iran, Rome, and Constantinople included prestigious gifts of swords, gold and silver vessels, jewelry, and garments, which were presented to aristocratic supporters and foreign dignitaries. Such exchanges between empires allowed artistic influences to flow in both directions. Even after the collapse of Iranian political control, the glory of the Sasanians was well remembered in the courts of the new Arab rulers and throughout Central Asia and China, celebrated in art, poetry, and ceremony.

Sasanian Drinking Vessels

The ritualized drinking party known as the bazm affirmed the high status of aristocratic men in Sasanian society. Precious metal vessels were used, including tall ewers for pouring wine, shallow bowls, and drinking horns. They were decorated with a variety of figures, such as animals alluding to the hunt, and women with food, flowers, and birds symbolizing the pleasures of the feast.

Sasanian Royal Vessels

Silver and gold vessels produced in Sasanian court workshops often served as prestigious royal gifts. Finely worked plates, cups, and bowls portraying the king and his family were presented to favored subjects in recognition of their loyalty and as symbols of high status.

The King as Hunter on Sasanian Plates

The image of the Sasanian king as an invincible hunter was the favorite decorative motif on silver plates produced in court workshops and presented to loyal followers. Owning such a plate was a great honor and marked its possessor as one who had a special relationship with the king.

Greek Myths on Sasanian Plates

Scenes of Greek myth circulated widely in Iran following Alexander the Great’s conquest of the region in the fourth century BC. Works decorated with such images continued to flow to the Sasanian royal court from Rome and Constantinople. These silver plates show how Greek mythological motifs were reinterpreted by Sasanian craftsmen, who may have sometimes misunderstood their original meaning.

Sasanian Gems, Medallions, and Coins

Seals carved from semiprecious stones were widely used throughout the Sasanian Empire by individuals, priests, government officials, and the royal court. Impressed into clay, the seals’ images served as signatures on documents. Some of the finest examples bear a portrait of the owner, attesting to the individual’s high status. The Sasanians issued an extensive series of coins in gold, silver, and bronze to facilitate trade, civic and military expenses, and taxation. The coinage is significant for providing stylized portraits of all the kings, each with a distinctive crown and an identifying inscription. The portraits appear on the obverse (front), while the reverse typically depicts a fire altar flanked by standing figures.

Minority Religions in the Sasanian Empire

Although Zoroastrianism served as the Sasanian state religion, other faiths had a

significant presence in the empire.

Judaism

Jewish communities had existed in Mesopotamia since the eighth century BC and had considerably increased in size with exiles from Jerusalem after the Babylonian destruction of the Temple there in 587 BC. In the Sasanian period, Judaism was officially recognized by the royal authorities. Religious academies were established at several cities, most notably Nahardea and Pumbedita on the Euphrates River (in present-day Iraq), where the formal study of the Talmud developed.

Christianity

Christianity made inroads in Mesopotamia at an early date, and by the beginning of the Sasanian period, there were already around twenty bishops in the region. The conversion of the Roman Empire, as well as Armenia and Georgia, to Christianity in the fourth century brought the Sasanian Christians into conflict with the authorities, who suspected them of disloyalty. But in AD 410, under the enlightened rule of Yazdgird I, the religion was officially sanctioned.

Manichaeism

Around AD 240 a doctor from Babylon named Mani created a new religion that sought to unite the teachings of Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and other religions through a doctrine that saw a stark division between the good realm of light and the evil realm of darkness. Manichaeism taught a rigorous behavioral code of ethics that would enable the individual to identify with the forces of light and goodness. Through a highly organized structure of bishops and presbyters, who employed illustrated books of Mani’s teachings, the religion spread quickly. Mani himself was welcomed by the Sasanian royal court for a time but eventually fell from favor and was executed in AD 274 or 277. Persian-speaking disciples carried the religion to Central Asia and China, where it found its most long lasting success.