Palmyra

Loss and Remembrance

The ancient city of Palmyra (“Place of Palms”), well situated at an oasis in the Syrian desert, flourished in the first centuries of our era. An earlier, pre-classical settlement there, “Tadmor in the wilderness,” is mentioned in the Bible as a foundation of King Solomon. Palmyrans grew rich through the caravan trade transporting silk, spices, gems, slaves, and other commodities between the Mediterranean and Persia, India, and as far east as China. In AD 267, Queen Zenobia led Palmyra in a revolt against the Romans; the city won brief independence but was sacked by Emperor Aurelian five years later.

Grand temples, colonnaded streets, and richly decorated communal tombs attest to Palmyra’s period of great prosperity under nominal Roman rule. The funerary portraits featured in this exhibition display details of dress, jewelry, and other attributes that reveal the distinctive cultural mix of the city’s Greek, Roman, and Parthian (ancient Iranian) inhabitants.

Though the monuments of Palmyra survived for millennia, the site has suffered greatly in the current Syrian civil war, which has resulted in thousands of deaths and the deliberate destruction of buildings and artifacts. The works presented here date from a time of seemingly greater cosmopolitanism and tolerance.

THE CLASSICAL WORLD IN CONTEXT

This exhibition is devoted to ancient peoples who encountered and engaged with the Greeks, Romans, and Etruscans. It highlights the connections between civilizations and explores how cultures developed through artistic, social, and political interactions. All but one of the sculptures on display have been lent by the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. Most were acquired by its founder, the Danish brewer Carl Jacobsen (1842–1914).

PALMYRAN PORTRAITURE

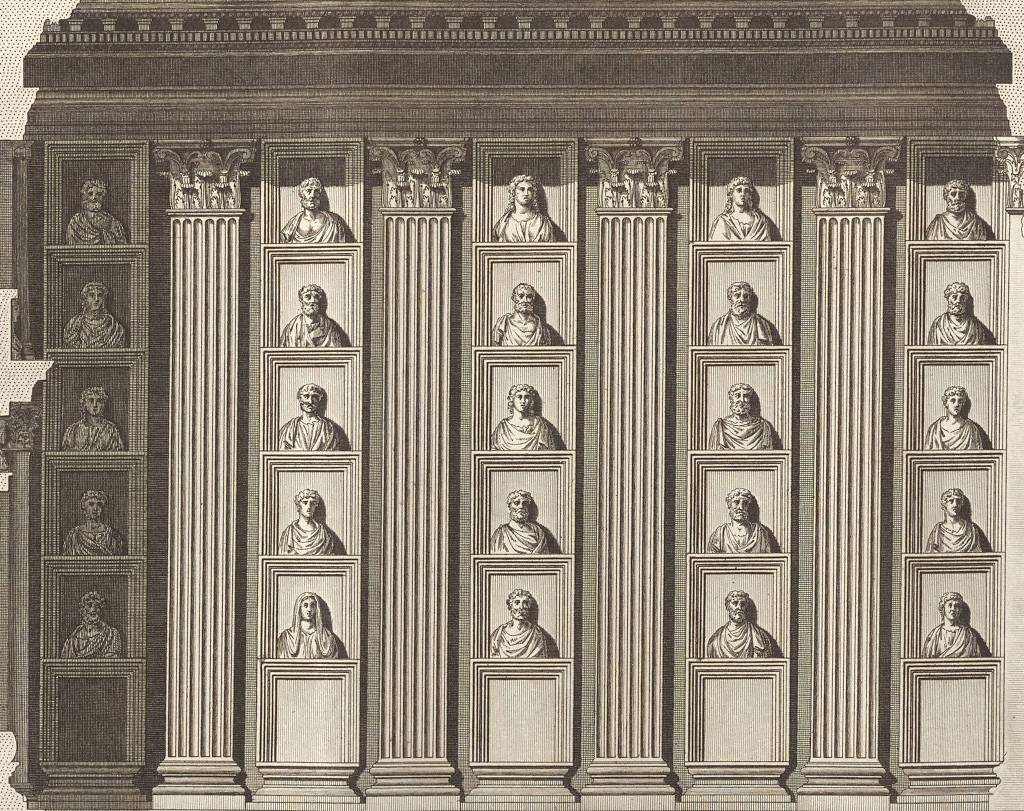

Inspired by Greek and Roman customs, Palmyrans erected statues honoring important citizens. Most surviving sculptures from the site, however, are funerary reliefs commemorating the dead. These images, carved from local limestone and then brightly painted, were arranged in rows within monumental tombs. There, they sealed loculi (individual burial niches) within towers; hypogea (underground chambers); and mausolea (temple-like structures), all of which contained hundreds of graves and vast galleries of multi-generational family portraits. Most reliefs bear inscriptions in Palmyran Aramaic. These express grief for the loss of the deceased, name family members, and often provide lengthy genealogies.

Some also include a precise date of death. These dates, reckoned according to the ancient Seleukid calendar, which began on October 1, 312 BC, help to establish the chronology of the over-three-thousand portraits currently in collections around the world. The Palmyran holdings of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, the source of all but one of the sculptures displayed here, are the largest outside of Syria.

FUNERARY RELIEFS AND PALMYRAN IDENTITY

Male and His Sons(?), AD 190–210, limestone. Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, Stanford Family Collection, Palo Alto JLS.17200 (left) and Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen IN 2775

Palmyran funerary portraits depict the deceased gazing forward, dressed in fine clothes. Men usually wear tunics and Greek-style cloaks; their professions are rarely indicated, though priestly status is sometimes noted. In early reliefs, women hold a distaff and spindle for working wool—traditional symbols of feminine virtue. With time, female portraits display richer jewelry and changing hairstyles, likely reflecting growing wealth from trade connections, as well as evolving fashions.

Although Palmyran reliefs present their subjects with idealized, generic features and neutral expressions, they nonetheless reveal deliberate and individualized choices. Those who commissioned and carved them selected from a repertoire of gestures, hairstyles, clothing, jewelry, and other meaningful attributes. In commemorating the dead, they sometimes also included representations of other family members. Palmyran portraits, while less naturalistic than contemporary Roman sculptures, likewise honor the deceased and embody familial aspirations and communal values.

PALMYRA TODAY

The buildings of Palmyra have inspired Western artists and architects since the late 1600s, when British merchants “rediscovered” the city. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980, Palmyra was attacked in 2015 and 2017 by the so-called Islamic State, which deliberately destroyed most of its best-preserved monuments. This iconoclasm was compounded by the brutal execution of many contemporary Palmyrans, including Khaled al-Assad, the retired director of antiquities and guardian of the site for more than forty years. The group also circulated videos of the smashing of statues in museums and has looted artifacts and sold them on the black market to fund its activities. Although Palmyra was retaken by Syrian government and Russian forces in 2016 and again in 2017, many of the temples, tombs, and other magnificent monuments that stood for centuries have now been reduced to rubble.