Manet and Modern Beauty

La Vie Moderne

The years around 1880 saw the culmination of Manet’s career as his generation’s foremost “painter of modern life,” to borrow a phrase from his friend Charles Baudelaire, a poet and critic. In innovative pictures set at fashionable Parisian locales and staged with models in his studio, Manet sought to characterize the women of his era—and to a lesser extent the men—for posterity. The parisienne, a social type that defined youthful, feminine chic, occupied much of his attention. Sporting up-to-the-minute fashions, the parisienne embodied for Manet the particular beauties of modern life.

Rather than join his younger Impressionist friends in their independent group exhibitions, Manet preferred to showcase his work in the official Salon, where he could reach a massive audience. He also mounted occasional solo shows, most notably in 1880 when he was invited to exhibit in the gallery affiliated with La Vie Moderne, a brand-new fashion and culture magazine. Introducing the public to his provocative cabaret, bar, and boudoir scenes and to his deft pastel portraits, this exhibition marked a new beginning for Manet. Though some critics found his racier subjects morally objectionable, others were happily surprised by his evident talent. Numerous works shown at the Vie Moderne gallery appear in the present exhibition.

Portraits of an Era

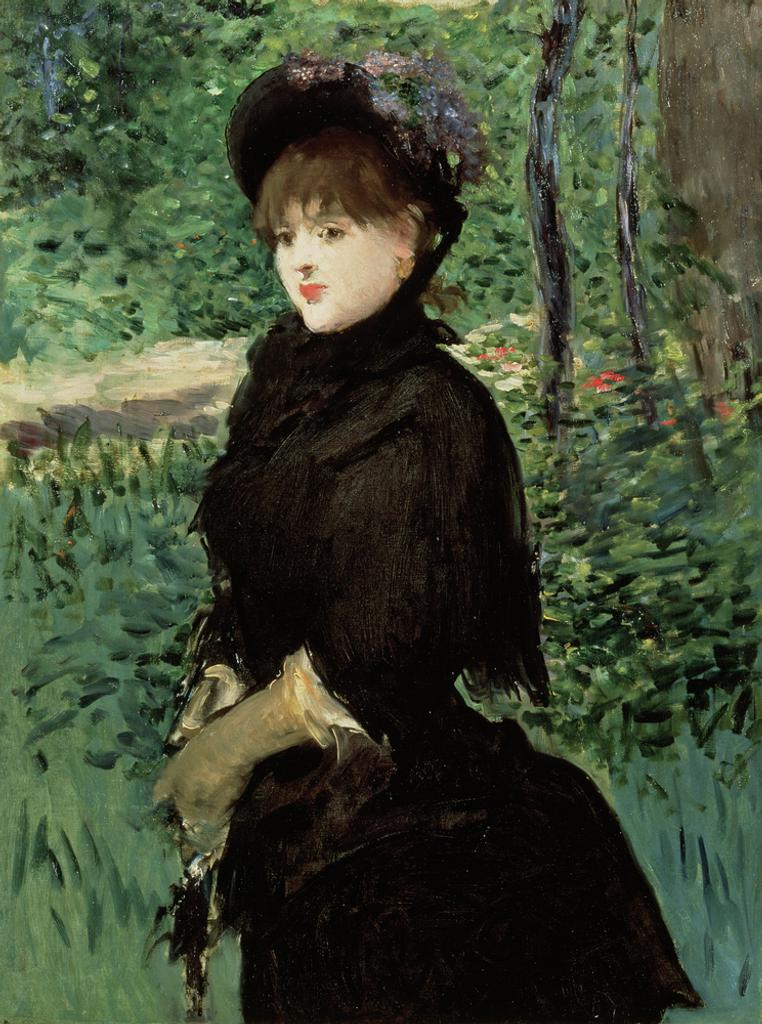

Portraiture was central to Manet’s self-conception as a painter of modern life. Not simply intent on recording individual likenesses, he aimed to capture his epoch by portraying representative social types—the chic parisienne or fashionable dandy, for instance—in their various modes of dress and deportment. Only rarely working on commission, Manet mostly solicited friends and relations to pose for him. Reflecting his extensive social milieu, his sitters ran the gamut from high society to the demimonde, from his intimate domestic circle to the world of the stage.

For Manet—a studio artist who insisted on working from the live model—portraiture posed one of the greatest artistic challenges: “to place a single figure on a canvas, and to concentrate all the interest exclusively on that figure without its losing its life and presence.” Manet aspired to do all this, as he put it, “in a single session.” The sense of vitality, immediacy, and spontaneity that his portraits convey, however, was hard won. Many sessions were required, often with much scraping down and repainting. Manet was notoriously demanding of his sitters and of himself. He felt that his status as an artist for the ages would ride on how well he distilled the historical character of his fleeting moment.

Manet’s Pastels

In the later 1870s, spurred by deteriorating health—and encouraged by the examples of his friends Edgar Degas and Berthe Morisot as well as his student, Eva Gonzalès—Manet took a new interest in the pastel medium. Using dry sticks of pure color did not require the same lengthy and laborious studio procedures as oil painting, and between about 1878 and his death in 1883, the artist turned out close to one hundred pastels. These are generally of modest dimensions, executed not on paper but on prepared linen canvases, which facilitated an unusual range of graphic effects but also sometimes made these works particularly fragile.

Though he produced a number of male portraits, nudes, and genre scenes in pastel, the majority of his pictures in the medium represent stylish young women, often in profile. Indeed, pastel was widely regarded throughout the nineteenth century as a quintessentially feminine medium, a colored powder akin to makeup. When Manet made his public debut as a pastellist at the Vie Moderne exhibition, one critic remarked, “The famous head of the Impressionist school here shows himself in a whole new light, as the painter of elegant women."

The Four Seasons Project

Manet meant his 1882 Salon painting Jeanne, which he also called Spring, to be the first in a series on the four seasons, each one emblematized by a stylish parisienne. Responding to trends in contemporary painting, popular illustration, and fashion advertising, Manet modernized a time-honored subject in European art. Doing away with the conventional symbolic trappings (a dove for spring, fallen leaves for autumn, and so on), he focused exclusively on the model, her chic apparel, and her decorative surround. More than the perennial rhythms of nature, Manet’s principal concern was the modern fashion cycle.

Antonin Proust reportedly commissioned the series, but it is unclear whether Manet intended a series from the outset or developed the idea after Jeanne’s Salon success and Proust’s acquisition of the picture. In any case, Proust undoubtedly encouraged Manet’s late-career interest in decorative painting, since he played an official role in promoting it as president of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Unfortunately, Manet never completed his seasonal cycle, painting only Autumn after Spring. This exhibition reunites the two works for the first time in nearly forty years.

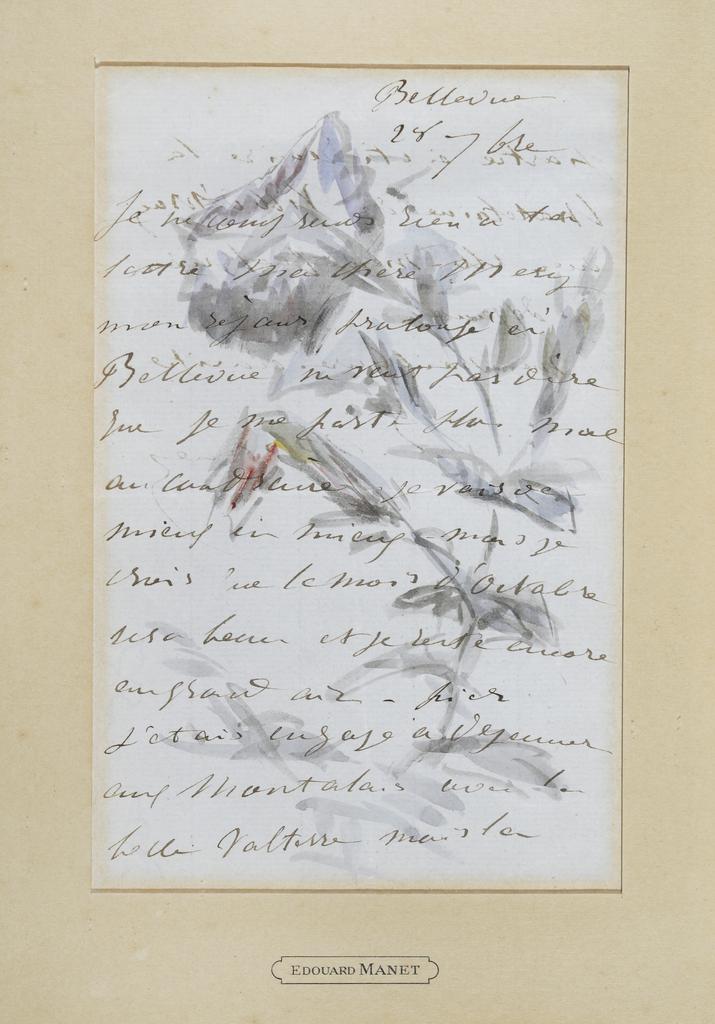

Manet at Bellevue

Tormented by increasing pain and stiffness in his left leg, the artist withdrew to the spa town of Bellevue in June 1880 to undergo a course of bathing treatments prescribed by his doctors. He remained there until November, enduring what would be the first of three periods of medical exile from Paris. Though accompanied by his family, Manet quickly grew lonely and bored with life in the “country,” as he called it, and began to fill the margins of his letters to friends and colleagues back in Paris or on vacation in Normandy with watercolor illustrations: plums, cats, flowers, and so on. Folded into envelopes and sent out into the world, these letters put a smiling face on their author’s isolation and illness.

From a technical standpoint, these works lack the graphite underdrawing generally apparent in Manet’s earlier watercolors, where he used his brush essentially to color in designs constructed with line. In the Bellevue watercolors, the underdrawing seems to disappear, and even complex forms are constructed with the brush alone. Though Manet did indeed draw some of these designs freehand with the brush, a recent comparative study suggests that he traced some of his more intricate illustrations from graphite studies in his sketchbooks, to enhance the illusion of effortless mastery.

Flowers, Fruit, and Gardens

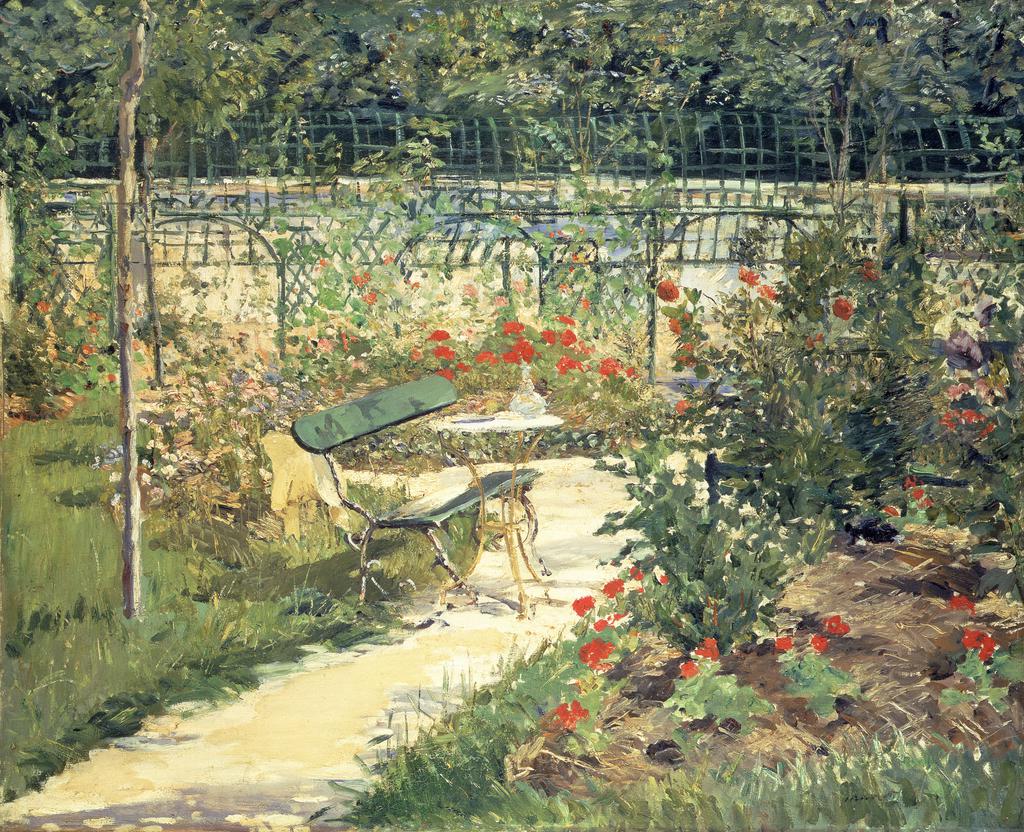

As Manet’s health continued to deteriorate, the painting of flowers, fruit, and garden scenes occupied more and more of his time. He spent his last two summers outside the city, taking rest cures at Versailles in 1881 and at Rueil in 1882. There he painted the gardens of his rental houses and pined for Paris. But even back at home, the compass of his world was shrinking: the progressive paralysis of his left leg confined him to his apartment and his studio just around the corner. He no longer visited friends or frequented cafés. Instead, café life came to him, as friends and acquaintances flocked to his studio to gossip and watch him work.

Some visitors—most famously Méry Laurent—came bearing flowers, which the artist adored and of which he once exclaimed, “I’d like to paint them all.” Paint them he did, turning out more than a dozen floral still lifes, for which he found a ready market among society collectors— though he also gave a few away as tokens of friendship. Unpretentiously arrayed on marble countertops and painted with sparkling vitality, these final still lifes are among the most beautiful pictures in his oeuvre, evidence for his evolution as a painter to the very last.