| Education | ||

| Exhibitions | ||

| Explore Art | ||

| Research and Conservation | ||

| Bookstore | ||

| Games | ||

| About the J. Paul Getty Museum | ||

| Public Programs | ||

| Museum Home

|

December 16, 2008–May 3, 2009 at the Getty Center

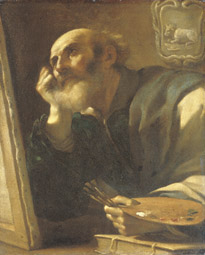

This exhibition tells the extraordinary story of a small group of artists who changed the course of art history. In the decades after the deaths of the great Renaissance masters, such as Raphael and Michelangelo, the art of painting was thought to have gone into steep decline. But then, in the late 16th century, the Carracci family of painters from Bologna burst onto the scene with tremendous energy and vitality, raising art to new heights. Their heroic achievement set standards that were to remain authoritative for more than 200 years. Here a selection of key works by the Carracci and several generations of their pupils and followers brings this artistic triumph to life. For them, the visible world became their principal source of inspiration, and nature was their teacher. Painting was about to enter a new era of creativity and lavish patronage, resulting in the glories of the Baroque age. |

||||||||||||||||||||

The Carracci Family Four hundred years ago the Carracci family of painters was as famous as Raphael or Caravaggio. Two brothers, Annibale and Agostino, and their cousin Ludovico challenged the artistic establishment of their day and revolutionized the art of painting. The academy they established in their workshop in Bologna influenced artists of the next generation, including Guido Reni, Domenichino, and Francesco Albani (all represented in this exhibition). |

||||||||||||||||||||

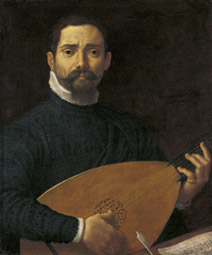

Portraiture This exhibition includes portraits by four of the greatest Bolognese artists—Annibale and Agostino Carracci, Guido Reni, and Guercino. None of them specialized in portraits, yet they possessed the gift of imbuing their works with an acute psychological insight and arresting authenticity that other painters of their day could rarely match. The young Annibale Carracci's skill at portraiture came in handy when he served as his own police sketch artist: he was so successful at recording the faces of some thieves who had attempted to rob him and his father that the men were soon caught and punished. |

||||||||||||||||||||

The Ideal versus the Real Should painters represent objects exactly as they appear, or should they aim to enhance the natural world in order to depict timeless perfection and ideal beauty? These two opposing views profoundly marked the artistic world of 17th-century Italy. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Guercino Because of his congenital squint (in Italian, guercio), Giovanni Francesco Barbieri became known as Guercino. He never studied with the Carracci, but he was deeply influenced by their theory and practice. In 1621 the Bolognese pope Gregory XV recognized Guercino's talent and summoned him to Rome to paint his papal portrait. The artist moved to Bologna after the death of Guido Reni in 1642 created new opportunities for him there. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Painting on Copper To protect their works from the ravages of time, artists have always looked for materials that promise permanence. Toward the end of the 16th century, copper plates came into use as a new support for painting. Bologna was one of the major centers of this technique. The copper was hammered or rolled into sheets about one-eighth of an inch (3 mm) thick. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Crespi's Seven Sacraments The seven sacraments (Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Confession, Extreme Unction, Ordination, and Matrimony) are understood by the Roman Catholic Church as a visible form of God's invisible grace. These rites were part of the everyday life of any 18th-century Catholic. Giuseppe Maria Crespi's series The Seven Sacraments—each painting representing one sacrament—is one of the greatest achievements of 18th-century painting. The artist presented the sacraments as he witnessed and experienced them himself, in contemporary dress, without idealization. |

||||||||||||||||||||

One Story, Three Painters Joseph, the hero of this biblical story (Genesis 39), was sold into slavery by his brothers. His new master, Potiphar, a minister of the Egyptian Pharaoh, promoted the diligent young man to overseer of his household. The handsome Joseph attracted the attention of Potiphar's wife, who pressed him to share her bed, undeterred by his repeated refusals. One day she found him alone in the house. Clutching his cloak, she pleaded with him once again to yield to her desire. Joseph fled, leaving his cloak in her hands. When Potiphar came home, his humiliated and vengeful wife accused Joseph of attempted rape, using the cloak as evidence. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||