William Blake: Visionary

Introduction

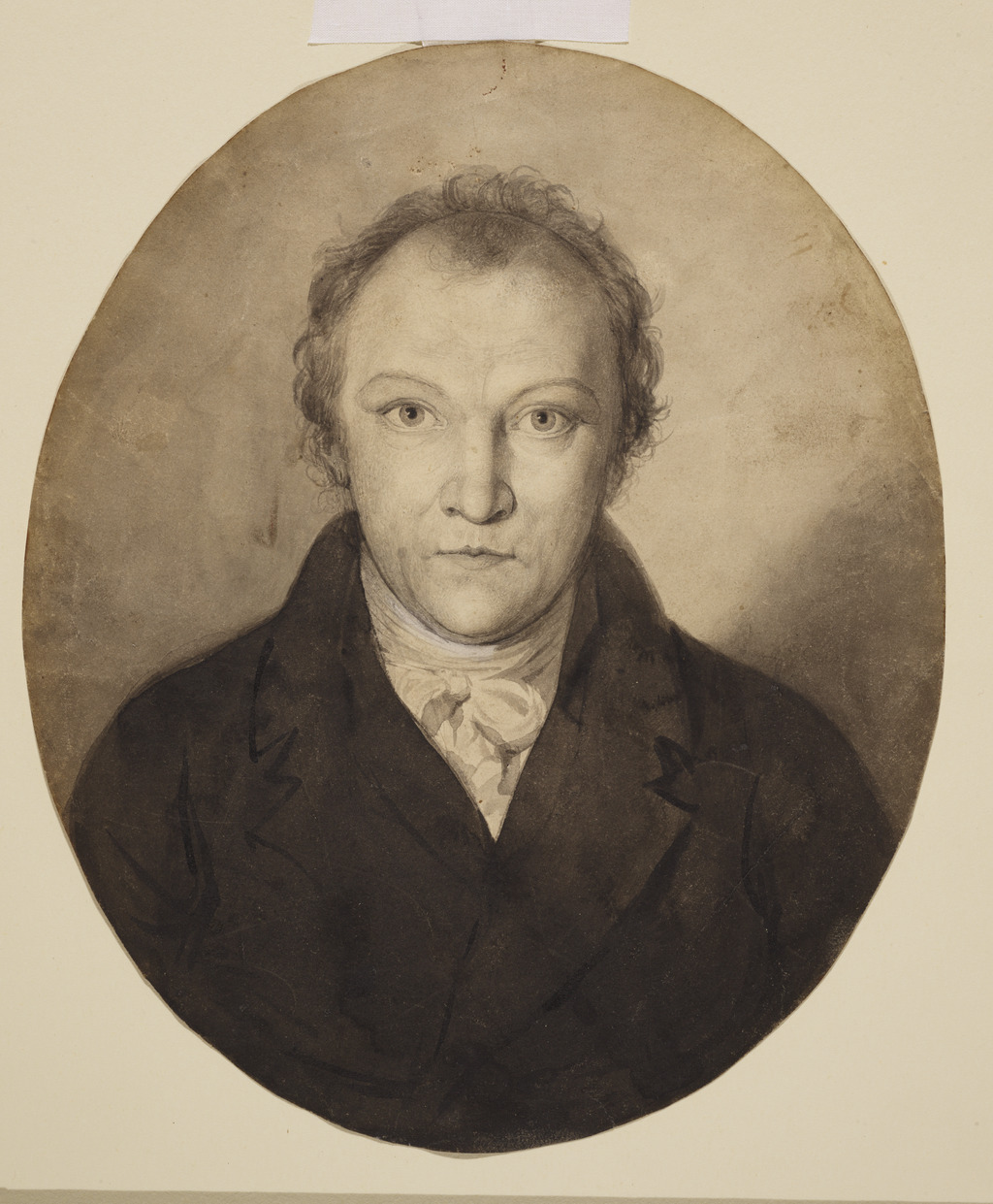

Now widely celebrated for his boundless imagination and unique vision, the printmaker, painter, and poet William Blake (British, 1757–1827) spent his life in relative obscurity. Beyond his traditional printmaking work, he employed innovative graphic techniques to combine his poetry and images. In this way he responded to the revolutions, political and economic repression, wars, and social unrest of his turbulent era, often veiling his criticisms in a complex and deeply personal mythology to avoid persecution by the British government. This exhibition explores themes in Blake’s life and career through some of his most acclaimed works, which have perplexed, delighted, and astonished for over two hundred years.

Professional Printmaker

London was a booming center for publishing in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While printmaking was a lucrative profession, it was also competitive and cutthroat. To succeed, one needed not only exceptional skill in printmaking techniques but also the ability to collaborate effectively with artists and publishers.

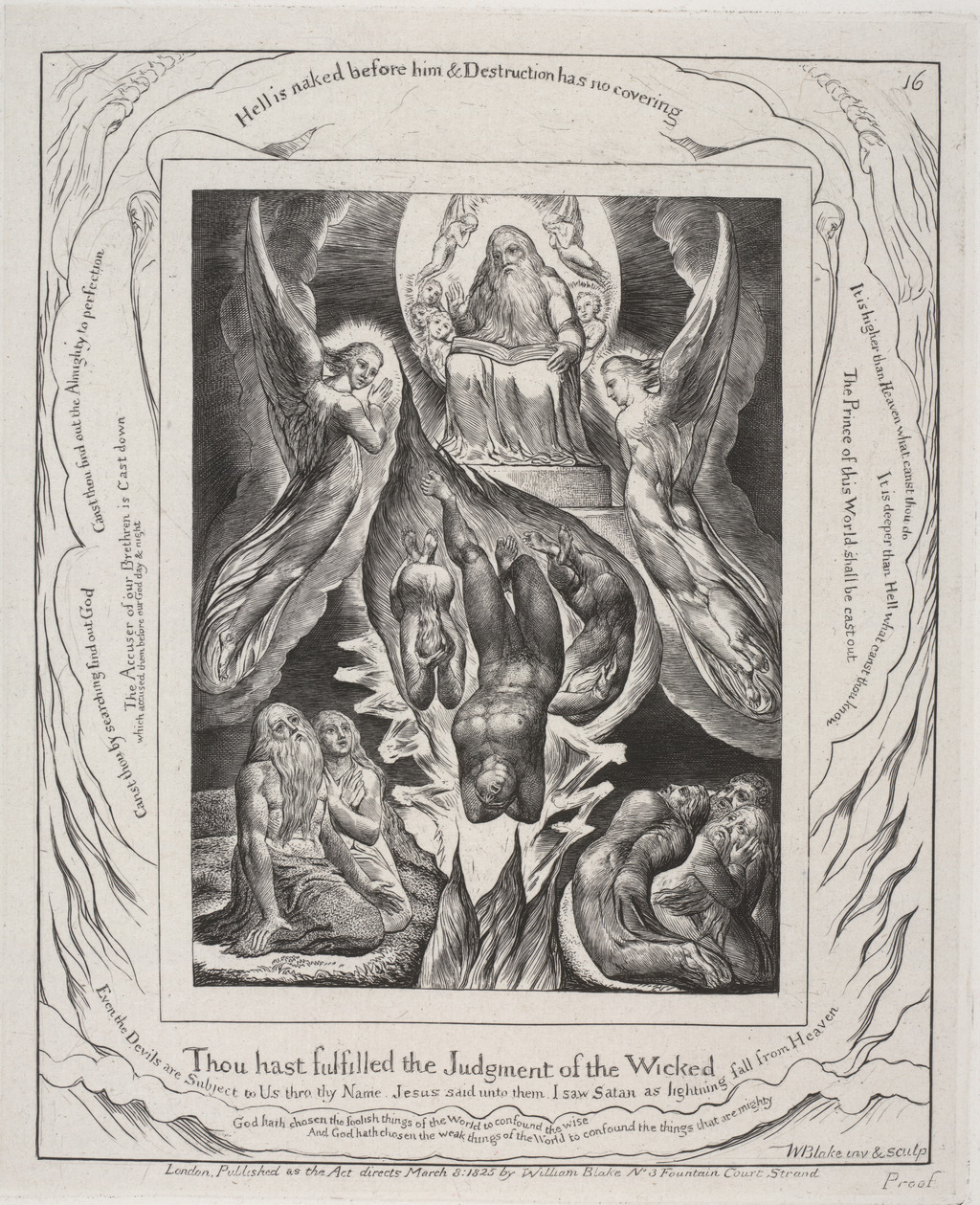

Throughout his life Blake’s main source of income was his printmaking. At first he specialized in producing prints based on images created by others. In the 1790s he began to receive commissions to design and engrave his own pictorial inventions responding to other authors’ texts. These projects allowed him a degree of creative freedom, but he still had to meet his customers’ expectations or risk losing business.

Independent Artist

Throughout his career, Blake was eager to break with his craftsman background and establish himself as an independent artist. He enrolled in the Royal Academy of Arts in 1779 and, following the conventions of the time, derived inspiration primarily from English history and literature as well as from the Bible.

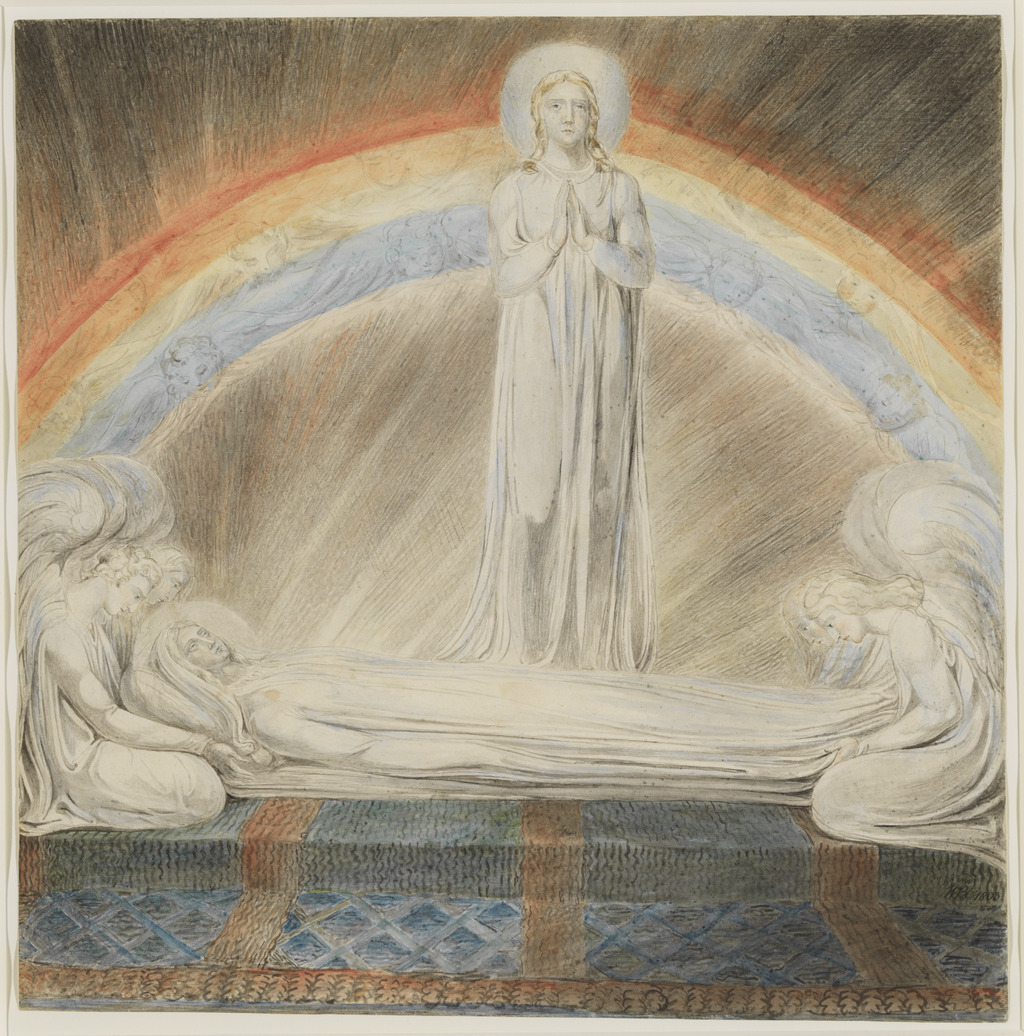

Yet despite his efforts, Blake failed to achieve commercial or professional success. Audiences favored images that were literal renderings of their textual sources, while Blake produced deeply personal commentaries on the underlying themes instead. Perhaps more importantly, Blake refused to work in oil paint, which was the most common, prestigious, and lucrative means of artistic expression. He associated oil painting with the muddying of forms, preferring tempera, watercolor, and printmaking, often reinforcing the contours with dark, definite lines.

Inventor

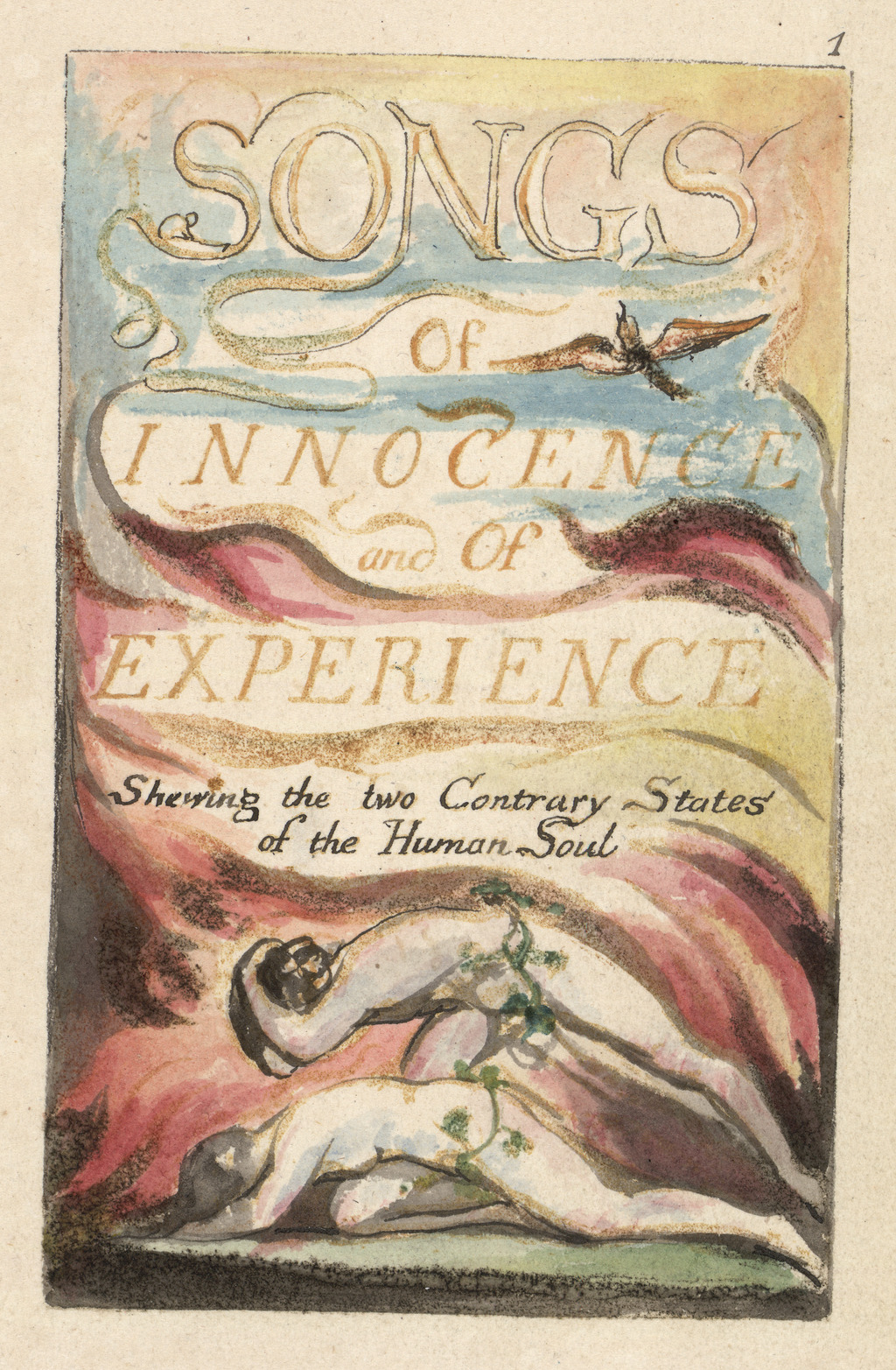

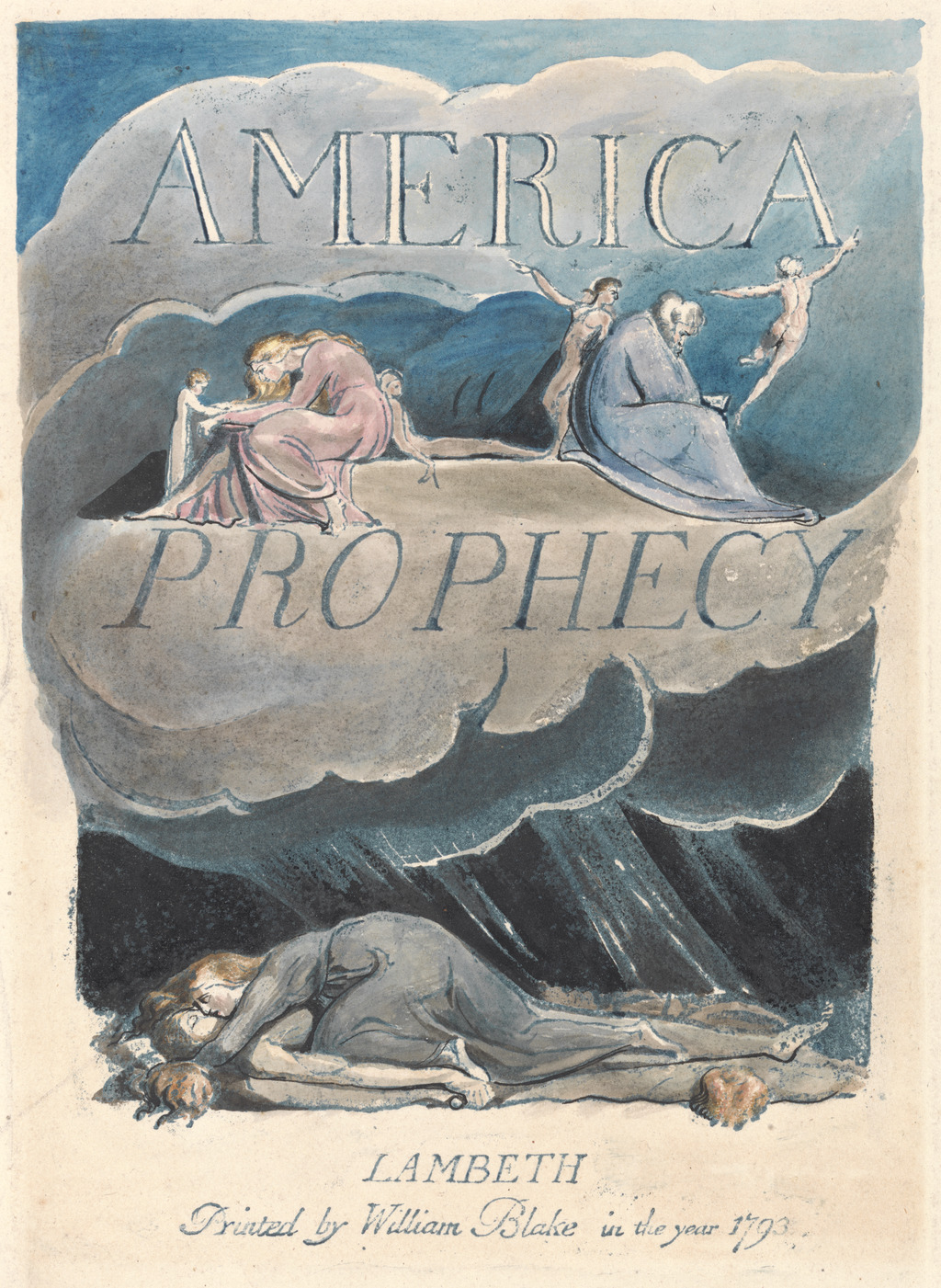

In an advertisement that appeared in 1793, Blake proudly claimed to have invented a new printmaking technique. His method, which he developed around 1788, is called relief etching, and is in fact an adaptation of traditional etching.

Relief etching allowed Blake to combine the arts of painting and poetry easily and effectively. By writing and drawing on a copper plate as if working on paper, he could print both text and image at the same time from a single matrix. Blake used relief etching almost exclusively to publish his own richly illustrated poetry. He referred to these publications as “illuminated books.”

Produced in multiple copies, the books can differ significantly in their organization and appearance, as Blake often changed the order of plates and varied the colors of ink used for printing and hand-tinting. Scholars identify each unique copy with a letter, such as “Copy A” and “Copy B.”

British Art World

In Blake’s day, the Royal Academy of Arts in London dominated the British art world. Founded in 1768, the institution aimed to elevate artistic production and taste by training students and organizing annual exhibitions. As the Academy promoted grand, historical paintings in the style of revered old masters, artists who aspired to greatness turned to the Bible, history, literature, and ancient Greek and Roman mythology for subjects.

Though Blake made many disparaging comments about the British art establishment, he longed for recognition from it. He formed meaningful and lasting relationships with fellow artists, some of whom had considerable influence on his style. Those closest to him even supported Blake by introducing him to potential patrons and commissioning works from him.

Visionary

Blake saw London convulsed by news of Britain’s defeat in the American Revolution in the 1780s, and by reports of bloodshed and social upheaval during the French Revolution in the 1790s. He lived in an era of British colonial expansion and experienced the anxiety caused by Napoléon Bonaparte’s aggressive military campaigns across Europe and beyond in the early 1800s.

Deeply engaged with the events of his day, Blake responded by creating a series of “prophetic books.” In these publications he commented on contemporary history but concealed his subversive views (for which he could have been imprisoned or hanged) with a self-constructed mythology. Blake conveyed his ideas on the page through words and images, using primarily his relief-etching technique. He avoided censorship by self-publishing these works.