Assyria

Palace Art of Ancient Iraq

In the ninth through seventh centuries BC, the kings of Assyria forged the greatest empire the region had known. Its armies conquered lands from Egypt, the eastern Mediterranean coast, and parts of Anatolia (Turkey) in the west to the mountains of Iran in the east. The Assyrian heartland itself lay astride the Tigris River in Mesopotamia, in what is today northern Iraq. Its original capital was the city of Ashur, known by this name since at least the mid-third millennium BC. In the period of the Assyrian Empire, the capital moved successively to Kalhu (Nimrud), Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad), and finally—the grandest city of all—Nineveh.

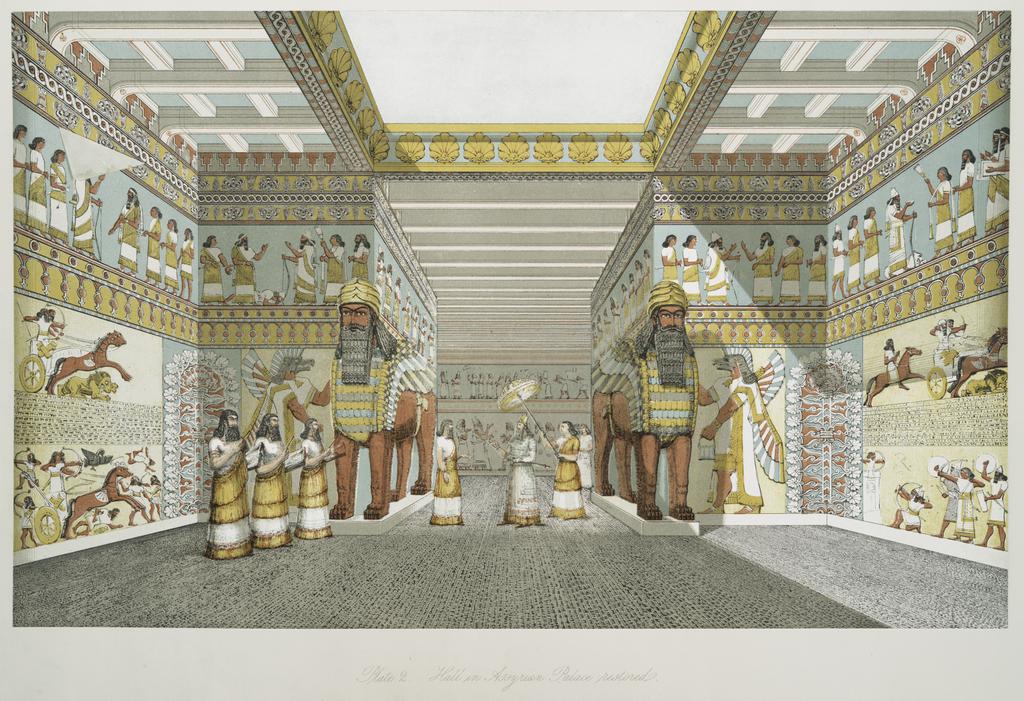

At each of these sites the kings built palaces to glorify their reigns, adorning the walls with superbly carved reliefs in gypsum and limestone. The scenes, which were originally brightly painted, presented an idealized image of the ruler through vivid depictions of battles, rituals, mythological creatures, hunting, building works, and court life.

Kings and their Cities

The reliefs in this exhibition come from the palaces of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) and Tiglath-pileser III (745– 727 BC) at Kalhu, Sargon II (722–705 BC) at Dur-Sharrukin, and the last great Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC) at Nineveh. Together these works, which include some of the masterpieces of Assyrian art, provide a representative overview of the primary subjects, styles, and artistic achievements of Assyrian sculptors.

Assyrian Palaces

Assyrian palaces were imposing complexes that served both as residences for kings and their families and as the venues for official diplomatic and ceremonial functions. Suites of rooms enclosed courtyards and provided royal living quarters, a throne room, reception halls, and spaces for administrative activities. Surrounding gardens and orchards were carefully maintained for the king’s enjoyment.

The Assyrians used mud brick as their primary building material, but the palace facades were often covered in white gypsum plaster that gleamed in the sunlight. Polychrome glazed bricks and wall paintings enhanced the architecture. Colossal stone sculptures depicting winged, human-headed bulls and lions guarded the entrance.

The most important rooms within the palaces were decorated with reliefs carved from gypsum or limestone, which were painted in vivid colors. Scenes in the throne room and reception halls emphasized the king’s military prowess and his status as the all-powerful ruler and builder. The subject matter of the reliefs in the king’s private quarters could include beneficent mythological creatures, rituals, and other subjects.

Sir Austen Henry Layard and Assyria

The British adventurer Sir Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) was the single most important figure in the rediscovery of ancient Assyria, excavating two of its capital cities, Kalhu (Nimrud) and Nineveh, in 1845–51. The reliefs on view in this exhibition, a number them uncovered by Layard, once decorated rooms within those palaces. In 1849 and 1853 Layard published folio-sized illustrations of hundreds of reliefs and other finds in The Monuments of Nineveh. His popular account of the excavations, Nimrud and Its Remains, also appeared in 1849 and quickly became a runaway best seller.