Photographer Dorothea Lange's life was marked by a sense of adventure, an ability to trust her instincts, a taste for freedom, and an intense compassion for people suffering misfortunes and injustice. Following her own philosophy of "go in over your head," she created memorable pictures of some of the darkest passages in twentieth-century American history.

Childhood

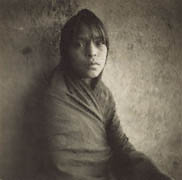

Lange was born in 1895 in Hoboken, New Jersey, the town to which her grandparents had come from Germany during the great wave of European immigration in the mid-1800s. When she was seven years old, Lange contracted polio, a disease that permanently damaged her right leg.

|

||

For the rest of her life she walked with a limp, an experience that some say gave her the empathy for human suffering so evident in her photographic work as an adult. In her own words, "I was physically disabled, and no one who hasn't lived the life of a semi-cripple knows how much that means. I think it perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me." Lange's mother was ashamed of her daughter's limp and urged her to hide her uneven gait if friends were nearby.

Lange's father abandoned the family when she was twelve; her mother then found employment at the New York Public Library in Manhattan. As a young girl, Lange spent a great many truant days in the city walking alone in sometimes threatening neighborhoods, visiting parks and museums, attending free concerts, and going to her mother's library. She developed a way of moving quietly, wearing what she called her "cloak of invisibility." This expressionless and inconspicuous demeanor allowed her to observe people in all sorts of situations and later served her well as she slipped unnoticed through migrant camps, rallies, and labor demonstrations while she photographed.

Early Career

Although Lange began studies to become a teacher after she graduated from high school, she soon announced that she planned to become a photographer. This surprised her family because at that point Lange had no camera and had never even taken a picture. Nevertheless, determined to learn, she found a job as a receptionist and darkroom assistant for portrait photographer Arnold Genthe. Although Lange was not artistically inspired by his flattering soft-focus portraits of women, she said, "I found out there that you can photograph what you are really involved with."

|

||

In 1918, at the age of twenty-two, she left New York to see the world with a friend. A robbery left her penniless in San Francisco, however, and there she stayed to open her own portrait studio within a year.

Her work was not especially innovative, but she was much in demand among the city's wealthy families. Her clients were pleased with the timeless quality of her images, the very element that Lange herself later rejected, saying, "Everything is shut out of many prints but the head—there's no background, no sense of place."

Marriage, Family, and a Deepening Vision

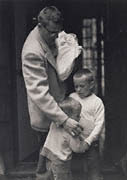

During the 1920s, Lange married the painter Maynard Dixon, had two sons, and began a lifelong struggle to care for her family while developing a photographic career so demanding as to often leave little room for any other pursuit.

|

||

As a young married woman, she remarked in an interview that an artist's wife bore a special responsibility to free her husband from petty, personal concerns. A few years later she openly longed for her own such freedom, having watched from her window fellow photographer Paul Strand go back and forth between home and studio each day, able to concentrate on his work as he pleased. Comparing the situations of male and female artists, she reflected, "There is a sharp difference, a gulf. The woman's position is immeasurably more complicated. What Paul Strand was able to do, I wasn't." Late in life Lange voiced her desire to have even a single year to devote exclusively to photography: "Just one, when I would not have to take into account anything but my own inner demands. Maybe everyone would like that, but I can't."

Although she enjoyed commercial success as a portraitist, Lange pondered how to deepen her own photographic vision. Looking to the work of a friend, photographer Imogen Cunningham, Lange tried making pictures of plants and landscapes while on vacation in 1929. Unhappy with her efforts, she took a walk alone in the mountains and, caught in a sudden storm, had a realization that guided the rest of her life as a photographer: "When it broke, there I was, sitting on a big rock—and right in the middle of it, with the thunder bursting and the wind whistling, it came to me that what I had to do was take pictures and concentrate upon people, only people, all kinds of people, people who paid me and people who didn't."

The Stock Market Crash and the Great Depression

The stock market crash in 1929 and the ensuing depression forced a change in Lange's career. There were fewer clients who could afford her portraits or Dixon's art, and things felt uncertain: "Not that we didn't have enough to eat, but everyone was so shocked and panicky. No one knew what was ahead." To save money, Lange and Dixon each moved into their respective studios and boarded their sons outside the city.

|

||

Lange found herself observing the unemployed people wandering the streets outside her studio. One day in 1933, on an impulse, she went outside to photograph a breadline.

The next day she hung one of the resulting prints, White Angel Bread Line, San Francisco, in her studio: "That's the first day I ever made a photograph actually on the street. I put it on the wall of my studio and customers, people whom I was making portraits of, would come in and glance at them. And the only comment I ever got was, 'What are you going to do with this kind of thing?' I didn't know. But I knew that picture was on my wall, and I knew that it was worth doing."

Lange left her studio again and again, photographing striking workers, men sleeping at the doorsteps of unemployment offices, and humble details—like tattered shoes and mended stockings—that told the story of a nation in economic decline. Although Lange had not initially considered herself an artist, in 1934 she had her first show in a gallery, in Oakland. Her work caught the eye of Paul Taylor, an economics professor who wanted to use her work to illustrate an article he wrote. The following year he became director of the California Rural Rehabilitation Administration and hired her to work with him. Together they interviewed migrant workers fleeing the dust storms on the Great Plains and created photo essays combining Lange's photographs, segments of the interviews, and Taylor's analysis. One of their joint projects was published in 1939 as the book An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion.

|

||

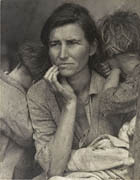

Work for the Farm Security Administration

Lange divorced Dixon in 1935 and married Taylor soon thereafter. Between 1935 and 1939 Lange worked for the Farm Security Administration (FSA; initially named the Resettlement Administration, or RA), which developed programs to help impoverished farmers. The FSA hired photographers to create pictures that supported government assistance for the unemployed farm workers, and it gave enormous latitude to this corps of photographers. Lange took advantage of this freedom to create some of the twentieth century's best-known and most compelling and sympathetic images of people in desperate circumstances.

She documented migrant workers, the unemployed, and rural families, conveying their dignity and spirit in the face of impossibly harsh conditions. Lange preferred to work spontaneously, believing that this method produced more effective images. She also made a point of never giving money or other material assistance to her subjects, feeling that the best way to help them was to publish her pictures and thereby expose their plight to the American government and the general public.

Working Methods

Coming out of the studio-portrait tradition as she did, Lange worked with a large camera on a tripod throughout the 1920s. She continued using large-format cameras when she began working in the field in the 1930s. Her Graflex camera was a large, heavy camera that produced 4-x-5-inch negatives. Lange had to hold it waist-high, looking down, rather than in front of her face and looking straight ahead. Despite her small size and the bulkiness of her equipment, Lange continued to use the Graflex in the field well into the 1940s. Later in life, after suffering long years of illness, Lange picked up a small, fast, lightweight 35 mm camera to document her foreign travels and her extended family in Berkeley.

![]() Video: Dorothea Lange's working method

Video: Dorothea Lange's working method

The War Years

The War Relocation Authority (WRA, the government agency charged with moving some 110,000 West Coast Japanese Americans to internment camps in response to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941) hired photographers to document its program. According to one writer, most of these photographers pictured the internment almost as though it were a pleasant company picnic, leaving out details such as the barbed wire, soldiers, and watchtowers.

|

||

Lange was among the photographers commissioned to record the WRA's activities. She documented many Japanese Americans on the eve of their forced departure to the assembly centers. Later she teamed up with photographer Ansel Adams to take pictures at the Manzanar concentration camp. Although adamant that Japanese Americans were full American citizens and ought to enjoy equal rights, Adams defended the government's actions and tended to gloss over the hardships suffered by Japanese Americans. Lange, however, was unabashedly convinced that the entire episode was "shameful." Referring to some anti-Japanese American billboards she saw in 1942, Lange wrote of "the billboards that were up at the time I photographed. Savage, savage billboards. This is what we did. How did it happen? How could we?" At one point she was so overcome by horror at the wartime incarceration of American citizens that she was unable to photograph at all. When she recovered, Lange went on to gently explain her role to the camp inmates and create images that reflected their strength and pride.

Soon after her WRA work ended, Lange received another government contract, this time to photograph minority groups on the West Coast. She also documented the wartime boom in Richmond, California, whose population and wealth grew with astonishing rapidity while its shipyards were busy making military vessels.

Postwar Projects and Reflections

Starting in the mid-1940s and continuing into the 1950s, Lange's ongoing ulcer-related health problems worsened and left her unable to work for long stretches of time.

|

||

As she gradually recovered, Lange worked on several important projects including intimate photographs of her own family and a moving portrayal of the daily life of a public defender at the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland, California.

Later she traveled with Taylor to Asia, the Middle East, and South America, taking photographs, writing letters, and keeping journals that reveal her constant questioning of her work, criticizing it and reflecting on its meaning. In Korea in 1958, she wrote to a friend, "The pageant is vast, and I clutch at tiny details, inadequate." In journal pages from her trip to Vietnam the same year, she asked herself, "Dorothea, is your photography just something you like to talk about? Does it satisfy your ego?"

In a 1963 journal entry written in Alexandria, Egypt, Lange muses: "A certain repetition grows in one's work. A certain habitual response, or channel of response. One sees one's own 'typical subjects.' The trigger finger operates. The reacting is immediate. . . . Have I now habits of vision? Have I lost flexibility and the ability to encompass the unfamiliar and record it or am I recognizing, deepening and intensifying, establishing the universal in the particular out of inner resources?"

Final Years

One of Lange's last projects was to assemble a portfolio drawn from some twenty-five years' worth of work documenting rural American women. She admired their hardiness, noting, "They are not our well-advertised women of beauty and fashion, nor are they part of the well-advertised American style of living. . . . They live with courage and purpose, a part of our tradition." Lange's compilation of pictures of these "women of the American soil" was published as The American Country Woman.

While working hard on preparations for a retrospective of her work at New York's Museum of Modern Art, Lange succumbed to esophageal cancer in 1965 at the age of seventy. Her last words, recorded by Taylor, were, "This is the right time. Isn't it a miracle that it comes at the right time. It comes so fast!"