|

This exhibition explores portraits in illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages (about A.D. 500–1500).

In contrast to modern portraiture, which strives to capture the accurate likeness of a specific person, medieval portraiture was primarily valued for its ability to express an individual's social status, religious convictions, or political position. Medieval portrait painters, rather than reproducing the precise facial features of their subjects, often identified individuals by depicting their clothing, heraldry, or other objects related to them. The goal of medieval portraiture was to present a subject not at a particular moment in time, but as the person wished to be remembered through the ages.

Like most medieval portraits, this image of Saint Blaise was created without even a written description of the subject's appearance. The artist concentrated his efforts on recording Blaise's forceful gaze and psychological intensity. The image may have been intended to inspire religious devotion, arresting the viewer's attention and bringing the subject to life.

|

|

|

There are almost no physical descriptions of Christ or any of the other holy figures who appear so frequently in medieval books and paintings. Artists invented these portraits by necessity, cleverly using facial types, costumes, and objects to help identify each figure. Christ, for example, appears with a cross in his halo, and the well-dressed noblewoman Saint Catherine appears with the sword that beheaded her. Saints became so commonly associated with these objects, or "attributes," that they were instantly recognizable to medieval viewers.

Some medieval portraits were renowned for their miraculous origins. The best known of these was a portrait of Christ that was said to have been produced when a pious woman named Veronica wiped Christ's face before his crucifixion. When she removed the cloth she found it imprinted with a perfect likeness of Christ's features.

In this image of Veronica displaying the cloth (called the sudarium), Christ's face appears to hover before the folded cloth, emphasizing its miraculous nature.

|

|

|

In this illumination from The Life of the Blessed Hedwig, a biography of Hedwig of Silesia (1174–1243), the saint looks solemnly out at the viewer, clutching a beloved ivory statue of the Virgin and Child.

Draped over Hedwig's arm is a pair of soft boots, which remind the viewer that she always went barefoot in imitation of Christ's apostles. Hedwig's lace-trimmed robe signifies her status as an aristocratic wife and mother before she became a nun.

The book's patrons, Duke Ludwig and his wife, commissioned this book to honor Hedwig, their revered ancestress. They are shown as small figures on either side of Hedwig. The portrait was intended to serve as an object of veneration not only for her descendents but also for the book's viewers.

|

|

|

Author portraits are one of the oldest categories of portraiture. In the Middle Ages, the purpose of such portraits was to affirm that the author's work was trustworthy. Some author portraits featured the writer hard at work, while others portrayed the writer accompanied by an object recalling some important aspect of the text. Portraits of artists only became common toward the end of the Middle Ages, when the development of observational portraiture introduced a new subject: the artist painting from a live model.

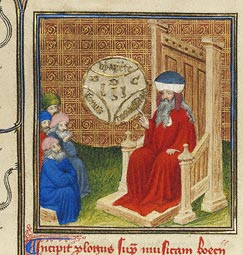

The scholar and philosopher Boethius wrote Concerning Music in the 500s. It was considered to be so authoritative that it continued to be used in universities for over a thousand years. This illumination from the early 1400s shows Boethius dressed as a medieval professor and occupying a chair that symbolizes academic authority.

Instead of the traditional author portrait of a writer working industriously, this image shows Boethius teaching his concepts to a group of students. He gestures to a diagram of musical theory that floats before him—a physical manifestation of the mysteries and intricacies of music. The attention and respect accorded to Boethius is reflected in the wide-eyed faces of his students, one of whom leans on his hand, lost in rapt contemplation.

|

|

|

|

|

Saint Luke Painting an Image of the Virgin (detail) in a book of hours, Workshop of the Bedford Master, about 1440–50

|

|

|

|

Saint Luke's profession as a portraitist is not mentioned in the Bible, but medieval legend credited him with painting a perfect likeness of the Virgin. Artists of the 1300s were the first to depict Luke as a painter, and many artists' guilds adopted him as their patron saint.

Here, Luke puts the finishing touches on a bust-length portrait of the Virgin, framing Mary's features with a heavy blue veil against a pure gold background on a small, round-topped panel.

This portrait type is based on icons ("likeness" in Greek), which were imported from the eastern half of the Roman empire, known as Byzantium, during the later Middle Ages. Because they looked very different from western European portraits, icons were thought to be exceptionally old and were often attributed to Saint Luke himself.

|

|

|

In medieval manuscripts, most portraits of living people had a religious function, showing the subject—often the owner or donor of a book—in prayer before Christ or a saint. Such portraits collapsed time and space, enabling people to imagine themselves before their favorite saints, where they could ask directly for help or guidance. Such portraits heightened the devotional experience book owners felt while saying their prayers.

These portraits were often conventional rather than realistic, so artists included coats of arms or other clues that helped identify the subject.

This illumination is found in the Gualenghi-d'Este Hours, the personal prayer book of Italian courtier Andrea Gualengho and his wife, Orsina d'Este. They are shown kneeling before Saint Bellinus along with two sons, probably from a previous marriage. Andrea's puffy cheeks, dark hair, and distinctive profile contribute to an exceedingly lifelike portrait.

As portraits like this one became more realistic through the late Middle Ages, patrons also demanded a plausible setting: here the donors adopt a respectful pose before the saint, but they also occupy the same space and are the same size as Bellinus. Andrea's whole family is expensively dressed, so that the image presents both their religious devotion and their very earthly riches.

|

|

|

A man kneels in prayer before the Virgin and Child (depicted on the facing page in the manuscript). He is accompanied by a woman who holds his coat of arms (later painted over). The man's personal mottoes, "Vie à mon desir" (Life according to my desire) and "Plus que jamais" (More than ever), appear in the margin.

These elements helped to identify the subject as Simon de Varie and to confirm his status as a pious member of the nobility. It is the startlingly lifelike portrait by Jean Fouquet, however, that powerfully conveys De Varie's identity.

The delicate brushwork reveals why the portrait's artist, Jean Fouquet, enjoyed acclaim even during his lifetime for his abilities as a portraitist. A contemporary wrote that the artist's "penetrating vision enabled him to render a perfect likeness," an assessment that modern viewers can still appreciate.

|

|