The Late Work

Study for the Portrait of Mäda Primavesi, 1912–13, Gustav Klimt. Graphite. Albertina, Vienna

» See Klimt's Portrait of Mäda Primavesi on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's website.

» See Klimt's Portrait of Mäda Primavesi on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's website.

In 1910 Klimt visited Paris and was influenced by Henri Matisse, among other contemporary French painters. His late portraits of women possess a French-inspired, colorful palette and lively brushwork. The overall background patterns and clothing of the sitters are often similar enough that they appear integrated. He became interested in Chinese and Japanese fabrics and costumes, which helped give rise in his drawings to a vocabulary of rapid-fire circular and comma-shaped pencil strokes.

Klimt never abandoned his intense exploration of the individual figure and its relationship to the flat surface of the sheet of paper. He also continued to crop the figure in allusion to the transitory aspect of life. Concurrent with this new influx of color and broken brushwork, his line work became interrupted and broken in its movement, thereby evolving in its expressiveness and its capacity to capture new dimensions of space and light.

The drawing at right is preparatory for Klimt's only major portrait of a child, Mäda Primavesi. (Klimt also painted a contemporaneous painting of her mother, Eugenia). Klimt drew several studies of Mäda, which are more natural and immediate, even in their forthright gaze, than his drawings of grown women. He is clearly interested in developing a range of girlish poses for the then nine-year-old, from winsome to brazenly self-assertive. In the studies, Klimt depicts Mäda in several poses. She sways forward and clasps her hands; in this one she sits on a high chair and dangles her feet. In the end, he devises a pose of unmitigated confrontation in which she stands frontally with splayed legs, and emphatically occupies the plane of the picture. See the painting on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's website.

Klimt never abandoned his intense exploration of the individual figure and its relationship to the flat surface of the sheet of paper. He also continued to crop the figure in allusion to the transitory aspect of life. Concurrent with this new influx of color and broken brushwork, his line work became interrupted and broken in its movement, thereby evolving in its expressiveness and its capacity to capture new dimensions of space and light.

The drawing at right is preparatory for Klimt's only major portrait of a child, Mäda Primavesi. (Klimt also painted a contemporaneous painting of her mother, Eugenia). Klimt drew several studies of Mäda, which are more natural and immediate, even in their forthright gaze, than his drawings of grown women. He is clearly interested in developing a range of girlish poses for the then nine-year-old, from winsome to brazenly self-assertive. In the studies, Klimt depicts Mäda in several poses. She sways forward and clasps her hands; in this one she sits on a high chair and dangles her feet. In the end, he devises a pose of unmitigated confrontation in which she stands frontally with splayed legs, and emphatically occupies the plane of the picture. See the painting on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's website.

- AUDIO: Albertina Curator Marian Bisanz-Prakken discusses this drawing.

Update Required

To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

Klimt's Sitters

Who were the women seen in Klimt's many portrait paintings and preparatory drawings? They were invariably wives and offspring of wealthy bankers and industrialists living in Vienna and were largely part of the city's Jewish community, and were patrons of Viennese artistic Modernism as championed by Klimt.Eugenia Primavesi (mother of Mäda, at top of page) and her husband owned paintings by Klimt and also financed the Vienna Workshops (Wiener Werkstätte), which manufactured Modernist decorative arts, textiles, and furniture. Serena Lederer and her husband, August, created the most important collection of Klimt paintings and drawings ever assembled. Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein, the daughter of a Jewish steel magnate (and sister of the famous philosopher Ludwig), paid for the Secession Building. Many of these Jewish patrons and heirs who were alive at the dawn of World War II either fled Vienna or perished, with their collections largely dispersed at that time.

Ria (Maria) Munk took her life at age 24 due to a failed love affair. Her grief-stricken parents commissioned Klimt to paint her posthumous portrait. The drawing above is a study for the painting. In it, the model's balletic stance and Klimt's energetic, gossamer pencil lines reach a finely tuned equipoise in this drawing. Ria Munk's parents rejected the finished portrait painting and Klimt transformed it into The Dancer.

The Virgin, 1911–13

Finished at the end of 1912 or the beginning of 1913 at the latest, The Virgin is one of the decisive figural allegories of Klimt's late career. The painting is a summation of Klimt's overarching theme of female erotic dream states, in which he explores its various manifestations over life, from virginity to mature sexuality.» See Klimt's painting The Virgin at the National Gallery in Prague (links to Flickr, image by jaime.silva).

The dominant figure of The Virgin lies at the center of the painting, with her swirling drapery covering her parted legs and her naked arms raised high over her entranced face. Six subsidiary female nudes encircle her. Klimt made many life drawings in order to distill the purest tincture of mood and pose.

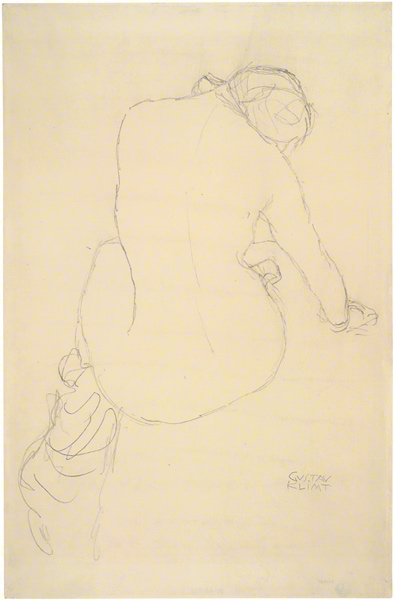

Klimt's preparatory drawings for The Virgin show an emphasis on contoured outlines, and some of the models display relative three-dimensionality and voluptuousness when compared to Klimt's earlier attraction to emaciated female nudes. The undulating contours of the drawings find echoes in the painting, where the interwoven female nudes swathed in drapery and flowers form a kind of bubble, pulsating through the universe.

With each of his drawings for The Virgin, Klimt strove to capture a specific mood. In the drawing above, the mood was one of closure and introversion. The combined sense of physical and spiritual encumbrance is conveyed by the rear-view, sedentary pose, bowed head, and single arm supporting the body's weight. This voluptuous figure is an early study for the emaciated nude in the lower left of the painting.

With each of his drawings for The Virgin, Klimt strove to capture a specific mood. In the drawing above, the mood was one of closure and introversion. The combined sense of physical and spiritual encumbrance is conveyed by the rear-view, sedentary pose, bowed head, and single arm supporting the body's weight. This voluptuous figure is an early study for the emaciated nude in the lower left of the painting.