|

|

|

|

The Chimaera of Arezzo (detail), Etruscan, about 400 B.C. Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana—Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze. Photo by Ferdinando Guerrini

|

The Chimaera of Arezzo traces the myth of Bellerophon and the Chimaera—the legendary fire-breathing monster comprised of a lion, a goat, and a serpent—over five centuries of classical art. It features the magnificent Chimaera of Arezzo, a large-scale Etruscan bronze statue on loan from the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. With a selection of pottery, coins, gems, and other objects, the exhibition explores the life and afterlife of an Etruscan icon.

Explore the themes of the exhibition:

Mythology | Iconography | Religion | Discovery | Afterlife

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

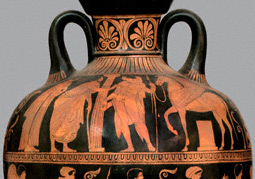

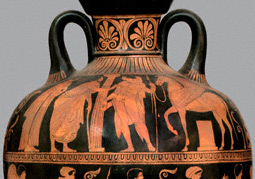

Lucanian red-figured amphora (detail), attributed to the Pisticci-Amykos Group, about 420 B.C. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei

|

|

|

|

First recounted in the epic poetry of Homer and Hesiod in the 700s B.C., the story of Bellerophon and the Chimaera endured for centuries as an allegory—of culture over nature, of spirit over matter, and of right over might.

The young warrior Bellerophon fled his native Corinth (in Greece) after murdering the local tyrant and sought refuge at the court of King Proetus in nearby Tiryns. There the queen, Stheneboea, falsely accused Bellerophon of seduction after he spurned her affections.

Rather than kill a guest, Proetus sent Bellerophon to King Iobates of Lycia (in present-day Turkey) with a sealed tablet instructing that the bearer be put to death. This amphora (storage jar) depicts Bellerophon holding the fateful tablet, as Proetus bids him farewell. Queen Stheneboea looks on from the left, while Pegasus, Bellerophon's famous winged steed, stands to the right.

|

|

|

|

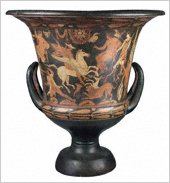

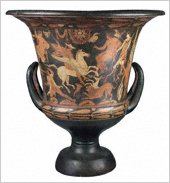

Faliscan red-figured calyx krater, about 370 B.C., terracotta, 18 1/8 in. high x 17 5/16 in. diam. Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome. Immagini della Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell'Etruria Meridionale

|

|

When Bellerophon reached Lycia, King Iobates was reluctant to do away with the youth himself. Certain that Bellerophon would perish, he commanded him to slay the Chimaera, a fire-breathing, triple-headed creature that was ravaging the Lycian countryside.

Riding into battle on his winged horse Pegasus, Bellerophon killed the formidable beast. For his success, he won Iobates' kingdom and the hand of his daughter, Philonoë. Later in life, Bellerophon dared to fly Pegasus to the home of the gods on Mount Olympus, but was cast down for his arrogance. Pegasus lived on as a constellation of stars.

This vessel depicts Bellerophon on his winged mount, hovering just out of range of the Chimaera's deadly flames and hurling a spear at the crouching beast below. It is typical of the colorful painted ceramics produced by the Faliscans, Etruria's closest neighbors.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

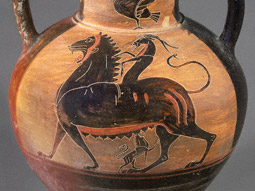

Faliscan olla, 700–650 B.C. Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana—Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze. Photo by Ferdinando Guerrini

|

|

|

|

Bellerophon's victory over the Chimaera was represented in ancient Italian art more than any other heroic exploit.

This vessel has one of the earliest known representations of a Chimaera. Brandishing a spear, a helmeted warrior stalks a composite beast with a curly pelt and a protruding tongue.

Because Pegasus is absent, it is unclear whether this is an illustration of the Bellerophon myth or a generic scene of hunting exotic and imaginary beasts. The lion (at center) and the sphinx (at left)—a hybrid creature with an animal body, wings, and a human head—would have been equally foreign to the Faliscan makers of this vessel.

|

|

|

|

Corinthian black-figured aryballos (detail), attributed to the Chigi Group, about 650 B.C. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

|

|

|

|

More certain depictions of Bellerophon and the Chimaera began to appear on Greek vessels in the early 600s B.C. These and other portable artifacts spread images of the Chimaera across the ancient world.

Potters in Corinth, Bellerophon's hometown in Greece, exported miniature oil containers such as this one throughout the Mediterranean. Here Bellerophon confronts the Chimaera, whose lion head snorts flames. Between the two is a tiny lizard about to fall prey to a bird, just as the Chimaera will succumb to Bellerophon. Below, a hare runs in vain from encircling hounds.

A Greek wine cup made in about 565 B.C. features a distinctive depiction of the scene: the Chimaera fends off the hooves of Pegasus while Bellerophon crouches below, thrusting his spear into the monster's shaggy belly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Etruscan scarab ring, about 400 B.C. The Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. Photo courtesy of Christie's

|

|

To the Etruscans and other Italic peoples, Bellerophon's slaying of the Chimaera seems to have had a religious significance: it may have been seen as a symbolic sacrifice that ensured the hero's successful journey to the afterlife.

Depictions of the myth frequently appear on gemstones, rings, and other objects deposited in tombs, such as a nearly pristine South Italian gold ring probably commissioned to adorn the body of the deceased. This suggests that Bellerophon was viewed as a benefactor or "patron saint," able to travel between worlds and intercede on behalf of the dead.

The Etruscan ring shown here features Bellerophon and the Chimaera engraved on blood-red carnelian, a gemstone that was associated with healing and courage, and which would thus have multiplied the scarab's potency as a protective talisman.

|

|

|

|

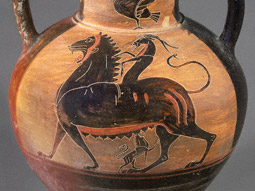

Etruscan black-figured neck amphora (detail), attributed to the La Tolfa Group, about 525 B.C. Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, Basel

|

|

|

|

|

Etruscan artists regularly reworked the myth of Bellerophon and the Chimaera, infusing the Greek narrative with local understandings of the Chimaera's essential nature. In Etruscan culture, monsters were associated with the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, and were sometimes depicted as nurturing mothers.

Here a maternal Chimaera suckles a baby feline that has yet to sprout its additional animal heads. What sort of creature will her cub grow up to be? A likely destiny is illustrated on the reverse side of this vase: a fierce male Chimaera is shown with two appendages, a goat and a snake-tipped tail, both of which belch fire.

|

|

|

|

|

The Chimaera of Arezzo, Etruscan, about 400 B.C. Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana—Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze. Photo by Ferdinando Guerrini

|

|

|

|

The Chimaera of Arezzo—the sole surviving large-scale sculpture representing the battle between Bellerophon and the Chimaera—had a religious function. An inscription written from right to left on the Chimaera's right foreleg reads TINSCVIL ("for Tinia"), marking the statue as an opulent offering to Tinia, the chief god of the Etruscan pantheon. The sculpture was probably commissioned by an aristocratic clan or a prosperous community and erected in a religious sanctuary near the ancient Etruscan town of Arezzo, about 50 miles southeast of Florence.

Hollow-cast in bronze from a wax model, the Chimaera of Arezzo is an outstanding example of the Etruscans' skill in metalwork. Its defensive posture suggests that it was originally part of a larger sculptural group that included Bellerophon and Pegasus.

|

|

|

|

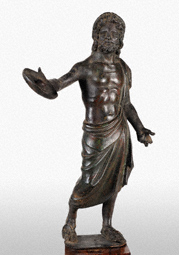

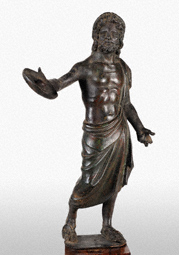

Etruscan statuette of Tinia, 300–200 B.C. Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana—Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze. Photo by Ferdinando Guerrini

|

|

|

|

|

The Chimaera of Arezzo was found along with a cache of small votive bronzes that further attest to the worship of the god Tinia.

This statuette from Arezzo shows Tinia wearing a tubular crown and a mantle. He holds out a phiale (offering dish) for pouring libations, an act performed by worshippers in sacred ceremonies. In his left hand he probably grasped a thunderbolt, symbolizing his authority as a dispenser of divine justice.

A small-scale statuette of a Chimaera likely also served as an Etruscan religious dedication. The small Chimaera bounds forward, its lion and goat heads turned in a hostile stare.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

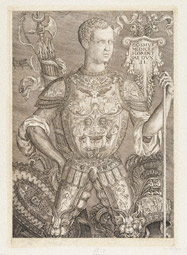

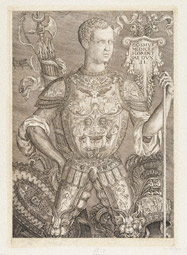

Cosmvs Medices Florentiae DVX II (Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Florence), Nicolò della Casa after Baccio Bandinelli, 1544. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute

|

|

The Chimaera was discovered on November 15, 1553, by workers building fortifications near the San Lorentino gate in Arezzo. Duke Cosimo I de' Medici claimed the sculpture and the accompanying bronzes for Florence and installed them in the Palazzo Vecchio. Like other members of the Medici family, Cosimo was an enthusiastic collector of local antiquities and encouraged the notion that he descended from Etruscan royalty.

Due to its fragmentary state when excavated, the Chimaera of Arezzo was initially misunderstood as a lion. Cosimo's court scholars used Greek and Roman coins in the ducal collection—such as a silver stater with the Chimaera—to reach an accurate interpretation of the statue. Over time, restorers reattached the Chimaera's left front and rear paws.

Cosimo spent evenings in the company of the Florentine goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, cleaning and repairing his prizes with jewelers' tools. Cosimo hailed the artwork as a symbol of his dominion "over all the chimeras," referring to his conquered foes.

The sculpture remained in the Palazzo Vecchio until 1718, when it was transferred to the Uffizi Palace. Since 1870, the Chimaera of Arezzo has made its home at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence.

|

|

|

|

The Chimaera of Arezzo, Theodor Verkruys, in Thomas Dempster, De Etruria regali libri septem (Seven Books on Royal Etruria), 1723–24. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute

|

|

|

The discovery of the Chimaera of Arezzo offered new evidence of Etruscan writing and religious beliefs, which attracted the curiosity of Renaissance historians. A 1582 sketch of the inscription on the foreleg, with a reconstruction of the Etruscan alphabet on the facing page, is the earliest recorded drawing of the sculpture.

The engraving of the Chimaera of Arezzo shown here was published in the first detailed study of Etruscan civilization, written in the early 1600s. By extravagantly praising the Etruscans' inventions and advanced civilization, author Thomas Dempster elevated them over their Roman conquerors and glorified his powerful Florentine patrons.

In this illustration the Chimaera is still missing its tail. The tail was not restored until 1785, when the Pistoiese sculptor Francesco Carradori (or his teacher, Innocenzo Spinazzi) fashioned a replacement, incorrectly positioning the serpent to bite the goat's horn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saint George and the Dragon (detail) in a Book of Hours, Follower of the Egerton Master, about 1410. The J. Paul Getty Museum

|

|

|

|

After virtually disappearing for several centuries, imagery of Bellerophon and the Chimaera rose to prominence again in the late Roman era (after about A.D. 200), when the myth became a popular subject in mosaic pavements.

In the early Christian era (A.D. 300–700), the Chimaera was seen as a manifestation of the devil. Christian images of Saint George mounted on a rearing horse and dispatching a dragon with his lance probably originated in the pagan iconography of Bellerophon killing the Chimaera. In this illumination from a 15th-century manuscript, the military saint's flowing cloak recalls the wings of Pegasus, but the monster is reptilian rather than feline.

Just as Bellerophon represented right over might, Saint George was an icon of the triumph of good over evil.

While Bellerophon lives on in the iconography of Saint George, the Chimaera of Arezzo endures as an emblem of Etruscan artistic achievement. As one of the great treasures of the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, it is a most fitting cultural ambassador in the inaugural exhibition of the J. Paul Getty Museum's partnership with Italy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|