|

|

|

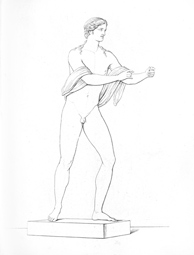

Apollo as an Archer (Apollo Saettante), Roman, 100 B.C.–before A.D. 79. Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei—Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples

|

|

A statue of Apollo in the pose of an archer was one of the first large-scale bronzes to be excavated at Pompeii, Italy. It was found in fragments in 1817 and 1818, centuries after the city was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

As part of a collaboration with the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, the sculpture was brought to the Getty Villa for conservation in 2009. What began as a project to clean the Apollo and ensure its stability for display developed into a rare opportunity to investigate the many stories it could tell.

This exhibition combines scientific and technical analysis with archival research to present the newly conserved Apollo, constituting yet another chapter in its compelling life history.

|

|

|

|

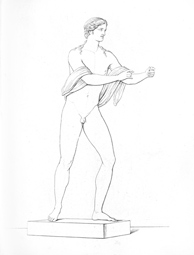

Diana as an Archer (Diana Saettatrice)

Roman, 100 B.C.–before A.D. 79. Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei—Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples

|

|

|

To the Greeks and Romans, Apollo was the god of prophecy, music, and healing. The exhibition also presents a bronze statue of Apollo's twin sister Diana (Artemis to the Greeks), goddess of the hunt. Only the upper part of the original statue survives. It was discovered in the Temple of Apollo at Pompeii in March 1817, just months before the Apollo was found.

Diana's pose, with her arms outstretched to hold a bow and arrow, matches that of the statue of her brother; the two sculptures were likely created as a pair. Unlike the statue of Apollo, this figure preserves its original eyes, which are made of bone for the whites and glass paste for the irises and pupils.

|

|

|

In June 1817 the majority of the Apollo, broken into three pieces, was found just north of the forum in Pompeii, not far from the Temple of Jupiter. (Visit this location on Google Maps.)

The statue remained incomplete until October 1818, when two veteran soldiers were walking along the northern city wall, over 300 meters away from the Apollo's initial findspot. (Visit this location on Google Maps.) Seeing a fox, the men chased it underground, whereupon they came across human bones as well as a group of bronze fragments: the Apollo's missing right foot, its right hand, and parts of its left arm.

Days later, the rest of the left arm was identified amid material that had previously been excavated. The bow and arrow that the Apollo once held have never been found.

Despite these scattered findspots, the statue has long been associated with the Temple of Apollo at Pompeii, based on the similar pose and style of the bronze figure of Diana discovered there in March 1817. Markings on a pedestal that match the Apollo's feet provide evidence for the sculpture's original location in the colonnaded courtyard of the temple. (Visit the Temple of Apollo on Google Maps.)

At the time of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, the temple had been undergoing repairs due to earthquake damage from the preceding years. This may account for the Apollo's discovery some distance away from the sanctuary. The statue may have been moved for safekeeping, or for melting down and reusing the bronze. How its extremities ended up even farther north remains puzzling. Nineteenth-century guidebooks presented a plausible thesis: that people trying to salvage precious materials in the aftermath of the eruption had made off with the bronze fragments, only to meet an unfortunate end themselves.

|

|

|

|

|

Right Eye from a Statue, Greek, 500–100 B.C., marble, obsidian, glass, and copper

|

|

The statue of Apollo was made using the lost-wax technique, which was widely employed in the ancient Mediterranean to produce large-scale bronze sculptures. The process involved creating a working model in wax and casting it in bronze in separate pieces. The resultant metal parts were then joined together, and the assembled statue's surface was finished.

Bronzeworkers sometimes fashioned eyes in different materials to give their figures a more lifelike appearance. A sculpture's head might be cast with empty sockets for the insertion of three-dimensional eyes, like the one shown here. The eye sockets of the Apollo, however, are not hollow, but cast with the head and slightly recessed (see detail). They may have served as backings for shallow inlays—as seen on the statue of Diana as an Archer.

|

|

|

|

|

Digital rendering of the Apollo showing the hole in the back and extent of repairs necessary after casting

|

|

A puzzling feature of the statue of Apollo is a large hole in the lower back. Covered by the sculpted drapery, it only became apparent through study of the statue's X-rays and endoscope photographs.

The hole was intentionally created, but its purpose is uncertain; it may have been an attempt to economize on metal. What is clear is that it caused problems during the casting, for it prevented an even distribution of molten bronze. Concentrated around the gap are numerous metal patches that were used to repair defects on the newly cast bronze. These can be seen on this digital rendering. Blue areas indicate "cold patches," bronze pieces hammered onto the surface. Orange spots are "hot patches," where molten bronze was poured to fill larger flaws.

|

|

|

|

|

The Restored Statue of Apollo, unknown artist, published in 1825

|

|

|

|

When the fragments of the Apollo were found, it was accepted practice to reconstruct the statue. The engraving at right, which is our earliest visual record of the Apollo, shows that its reconstruction was complete by 1825. It also suggests that the hanging ends of the drapery, which were never recovered, were re-created.

The figure was reassembled around an internal iron armature that was inserted through the left leg. Individual fragments were joined together using iron straps secured with brass screws and solder. Some gaps were repaired with pieces of modern metal that were shaped to fit.

The restorers aimed to hide signs of their intervention. The screws would have been visible on the exterior of the statue, which had been extensively cleaned. The final step, therefore, was to produce an overall surface coloring that looked ancient and allowed the screws to blend in with the surrounding metal. The restorers went to great lengths to imitate an ancient patina, applying pigments to create a suitable greenish color.

|

|

|

|

|

Getty Museum conservator Erik Risser working on the Apollo. The drapery shown here is from the later 19th-century restoration.

|

|

The conservation of the Apollo at the Getty Villa, which took place in 2009 and 2010, focused primarily on two objectives. The first was to secure the join at the right ankle, where 19th-century repairs had failed. The second was to address structural concerns regarding the sections of drapery hanging from both arms.

Study revealed that the drapery ends were neither ancient nor from the statue's initial restoration before 1825, but were added during a later phase of work completed by the mid-1860s.

Since their weight compromised the sculpture's stability, they have been removed by Getty conservators and are on view separately in the exhibition. Using archival drawings from the 19th century, the drapery ends have been recreated in epoxy and attached to the statue. Thus the figure now appears as it was displayed in Naples shortly after its discovery.

|

|

|

Situated in the center of Naples, in the 16th-century Palazzo degli Studi, the National Archaeological Museum holds one of the most important collections of classical antiquities, including such renowned sculptures as the Farnese Hercules and the Farnese Bull, as well as the mosaics, frescoes, and statues discovered at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae. The origins of the museum go back to 1777, when King Ferdinand IV conceived of a new institution for the arts in Naples and created the Real Museo Borbonico. The museum continued to grow through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with the incorporation of other collections, as well as finds from the numerous excavations at ancient sites throughout the region.

More information about the National Archaeological Museum in Naples is available on their website. (Website is in Italian.)

|

|

|

The exhibition has been organized in collaboration with the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, and the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei. All photographs of the statue of Apollo are courtesy of the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei.

|

|