- Gallo-Roman, from Saint-Romain-en-Gal, France, AD 150–200

- Stone and glass tesserae, 385.9 cm × 457 cm

- 62.AH.2.1–.36

Provenance

This mosaic was discovered in 1899 in a Gallo-Roman villa at Saint-Romain-en-Gal in southern France, located on the right bank of the Rhône, near Lugdunum (present-day Lyon).1 The site was a suburb of Vienne, one of the main centers of mosaic production in the region. C. Grange, the owner of the property on which the mosaic was found, reportedly uncovered in the same area at least two more mosaics, which he unsuccessfully attempted to sell to various museums and ultimately reburied.2 In 1911, two businessmen, Albert Vassy and Claudius Guy, became aware of the earlier excavations and purchased the property specifically to recover and sell the mosaics. In 1912, they re-excavated and lifted the Getty mosaic together with two additional pavements.3 There is no record of the whereabouts of the Getty mosaic following its removal, but one of the other two mosaics was acquired by the British Museum in 1913, and it is likely that the Getty mosaic was offered for sale at the same time.4 Subsequently, records of the Joseph Brummer Archive indicate that the mosaic was owned by the Brummer Gallery twice: in 1927, when it was purchased from one Widinger (or Weidinger), possibly Desire Weidinger of St. Cloud, and sold the following year to William Randolph Hearst, and in 1941, after Hearst’s death.5 J. Paul Getty purchased the mosaic in 1949 and donated it to the J. Paul Getty Museum in 1962.6

Commentary

A bust of Orpheus wearing a Phrygian cap decorates the central emblema (1.9 × 1.9 meters) of this mosaic.7 The head is framed by a hexagon and bordered by six additional hexagons containing a variety of reclining animals, including a bear, a goat, a male lion and a female lion, and two other felines. This honeycomb pattern is itself enclosed by a large hexagon within a circular guilloche border. Geometric shapes—a diamond within a rectangle—fill the six spaces left between the hexagonal animal panels. The entire composition is bordered by a square frame with personifications of the four Seasons in the corners: Summer occupies the upper left; Fall is in the lower left; Winter is in the lower right; and Spring is in the upper right.8 A 1912 photograph shows the floor in situ (fig. 8), including the pattern of intersecting black-and-white circles inset with crosses (also in the Getty’s collection) that surrounded the emblema. In the corners of this geometric background are four small rectangular panels depicting birds within frames composed of triangles.9 The outer border of the floor is decorated with a guilloche bordered by a meander pattern.

Orpheus, the mythical musician and poet from Thrace, was famous for his descent into the Underworld to retrieve his dead wife, Eurydice. The scene most frequently represented in Greek and Roman art, however, is the moment when every living creature gathered around Orpheus; the music from his lyre was so divine that it enchanted not only the wild beasts but even the rocks and trees of Mount Olympus.10 The event, often depicted with Orpheus holding his lyre and surrounded by numerous animals, appears in two different iconographic traditions: narrative, with all of the figures interacting in a single space, and allusive, with Orpheus and the animals in separate compartments, usually incorporated in a larger geometric design. The Getty’s mosaic exemplifies this latter, so-called multiple decor design, a local style composed of a grid-like framework filled with a series of related figures or scenes. This type of mosaic was especially popular in the upper Rhône valley in the second century AD, and the majority of examples have been found at Vienne.11

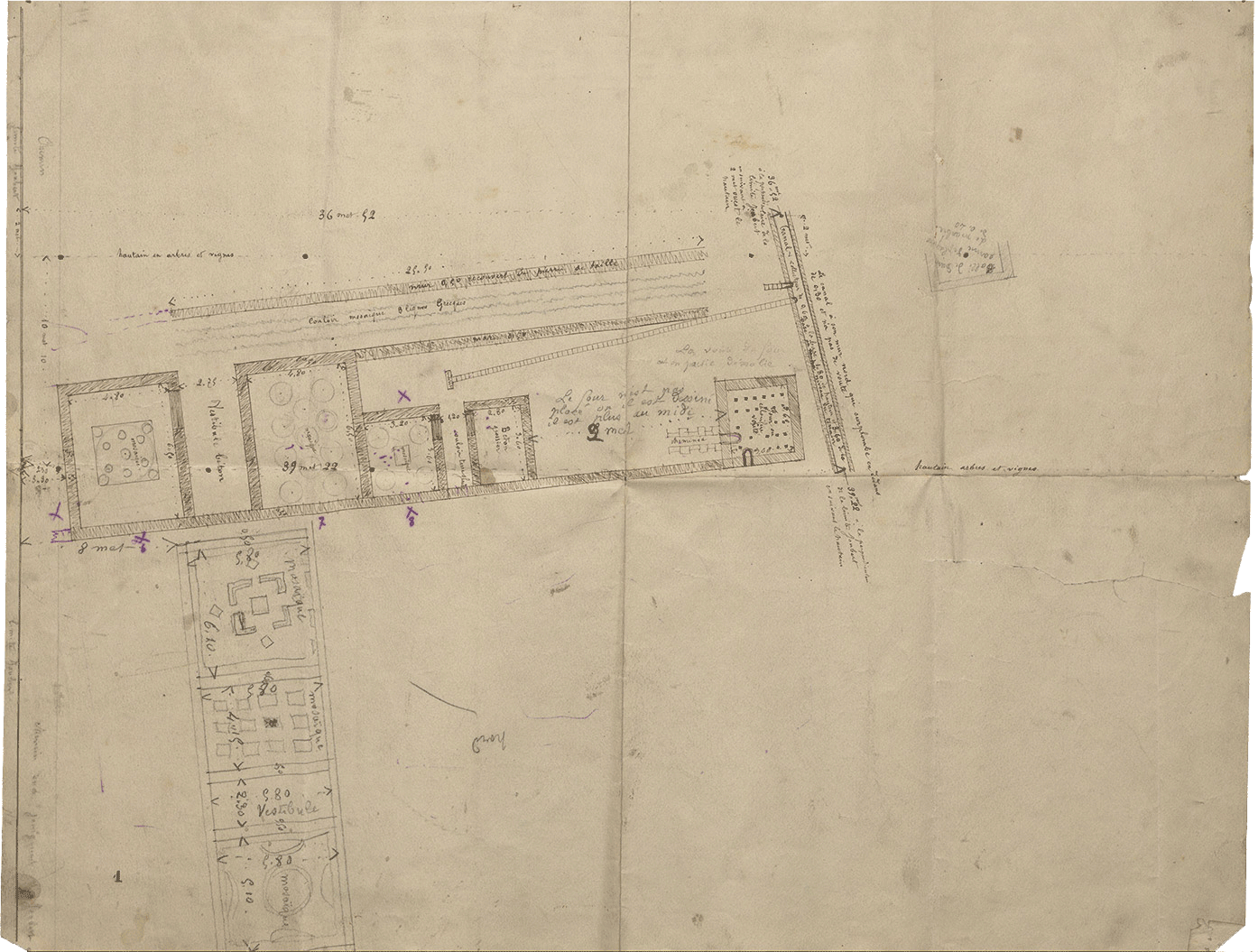

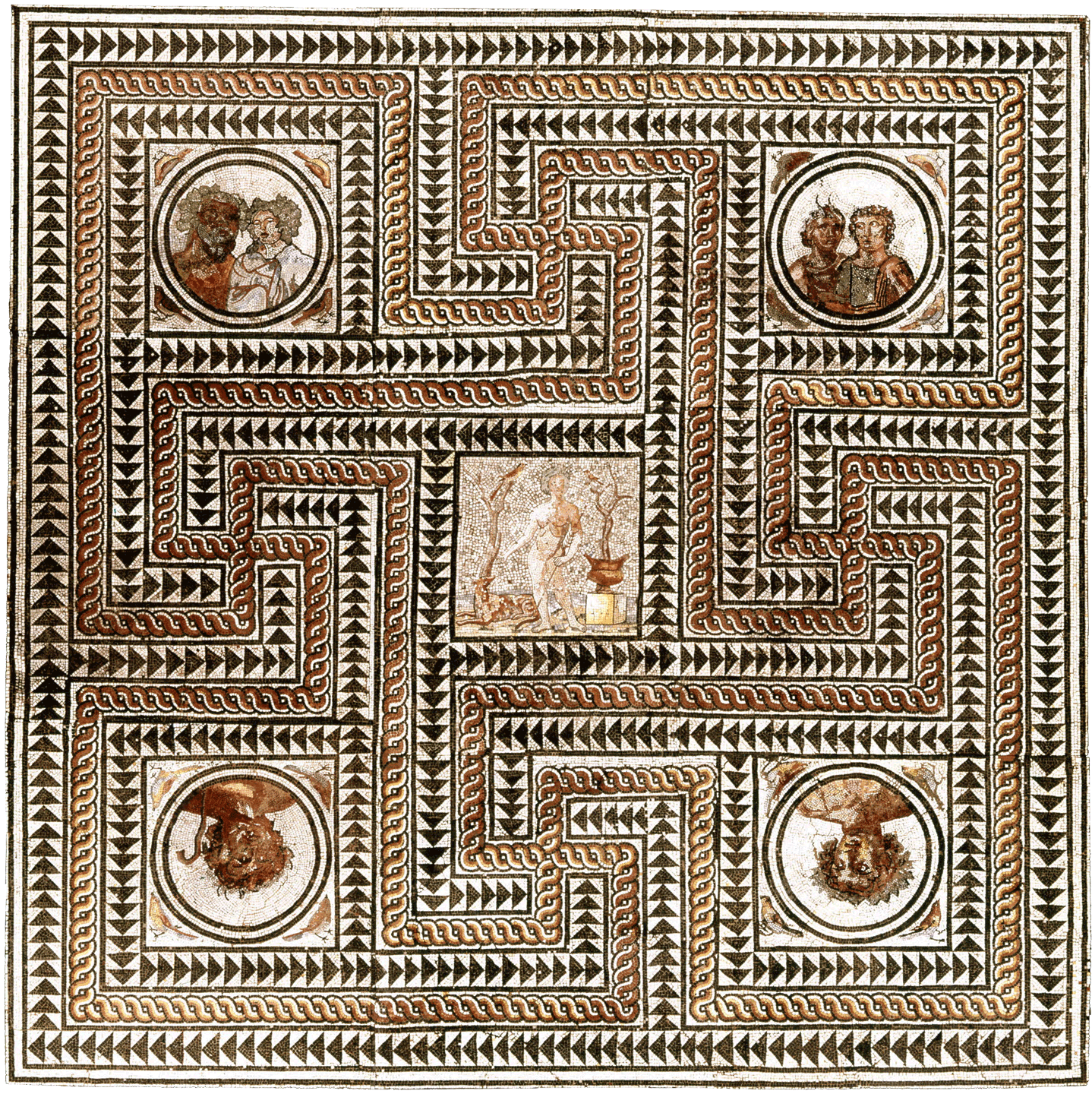

The Getty Museum’s Orpheus mosaic was one of seven elaborate mosaic floors discovered in the same villa at Saint-Romain-en-Gal. The plan of the building, known only in a sketch preserved in the Joseph Brummer Archives, shows a series of rooms accessed by a corridor (fig. 9).12 Three of the mosaics, including the Orpheus, were found in 1899.13 One of these, now in the British Museum (fig. 10), is composed of several busts set within an intricate geometric design of interlacing swastikas composed of triangle patterns and guilloche bands. The central emblema, a modern restoration depicting Silvanus, originally represented Dionysos holding a thyrsus (staff topped with a pinecone) and a krater. Four roundels in the corners contain busts of Silenus and a maenad, Pan and a maenad, a satyr, and Dionysos.14 The third mosaic discovered in 1899, now in the Musées de Vienne, is decorated with ornamental geometric and floral patterns arranged in hexagons and two kantharoi in circular medallions.15 Investigations of the same property in 1902 uncovered four additional mosaics.16 The most elaborate of these displays a central image of Hylas and the Nymphs (fig. 11).17 Like the Getty mosaic, this figural scene is relatively small in comparison to the larger geometric patterns, which are surrounded by a series of half circles and spandrels decorated with shells and floral motifs. The other three mosaics were more fragmentary. One preserves a centerpiece with two birds perched on an amphora; the second is a small piece with a rectilinear pattern and a guilloche; and the third consists of a corner depicting a female head, possibly a Season, with a series of floral patterns in squares running along one edge of the mosaic.18

Although some of the mythological themes represented in the mosaics of this Gallo-Roman villa are related—Orpheus was associated with the origin of the mysteries of Dionysos in Thrace, and Orpheus and Hylas joined the expedition of the Argonauts—without a complete plan or detailed description of the villa itself, it is difficult to identify an iconographic program or to understand the relationship between the mosaics and the architectural spaces they decorated.

Comparanda

A series of additional multiple decor mosaics from Vienne resembles the Getty mosaic in theme and composition.19 One mosaic pavement also from Saint-Romain-en-Gal similarly depicts Orpheus in a square emblema in the center, but the surrounding honeycomb pattern with animals covers the entire floor instead of being set within a geometric background.20 Another example composed of octagons in an arrangement comparable to the Getty mosaic was found in the House of Orpheus in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) at Vienne, where it decorated the frigidarium of a private bath.21 Indeed, the motif of Orpheus and the animals was popular on mosaics throughout the Roman Empire.22 A variation of the type—a black-and-white mosaic divided into nine intertwined circles with Orpheus in the center—comes from Santa Marinella, near Civitavecchia, on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea, northwest of Rome.23 One of the closest comparisons, however, was discovered at Thysdrus (present-day El Djem) in Tunisia.24 Here a central medallion decorated with a bust of Orpheus in an octagonal frame is surrounded by eight additional octagons, each containing a tondo with a different reclining animal; four smaller squares between the compartments hold birds. In a similar composition from Bararus (present-day Henchir-Rougga, near El Djem), the figures occupy a series of circular wreaths arranged in a grid pattern.25

Condition

A photograph in the archives of the Musées de Vienne, presumably taken in 1912, shows the mosaic in situ but already cut into sections for removal.26 At that time, it was reportedly reinforced with concrete and divided into twenty-two pieces for transport.27 During the treatment of the mosaic that took place before it entered the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, many details were restored, including the animals and the shoulder of Orpheus. The Season in the upper left corner is a modern restoration based on the original, which was preserved in situ.

Bibliography

De Villefosse 1899, 102–3; Bizot 1899, 1–2; Bizot 1903, 1; Lafaye 1909, no. 219; Vassy and Guy 1913, 628–32; Le Moniteur Viennois 1913, 2; La dépêche de Lyon, 1913; Le Progrès, 1913, 1; Lyon republicain, 1913; Fabia 1923, 99; Hammer Galleries, New York 1941, 329, lot 563; Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York 1949, lot 863; Getty and Le Vane 1955, 83–84, 153, 247–48; Stern 1955, 69, no. 5; Langsner 1958, J14; Getty 1965, 20, 82–83; Stern 1971, 130–35, fig. 10; Vermeule and Neuerburg 1973, 52–53, no. 112; Lancha 1977, 72–73, fig. 29; Lancha 1981, 229–32, plates 126–27, no. 373; Armstrong 1986, 143, fig. 10; Lancha 1990, 111–12, no. 52.

-

The discovery of the mosaic was first published in de Villefosse 1899, 102–3, which reported the mosaic as having been found at the nearby site of Sainte-Colombe. Early newspaper articles, however, describe Saint-Romain-en-Gal as an enclave of Sainte-Colombe, possibly accounting for the confusion. For more on this identification, see Stern 1971, 131–35. ↩

-

Grange’s farmer, M. Prost, discovered the mosaic while working in a vineyard on the property. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, no. 219. Vassy and Guy 1913, 628–32, indicate that the mosaic was uncovered and removed in 1912. ↩

-

The British Museum purchased one of the mosaics in 1913 (inv. no. 1913, 1013.1). ↩

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, has digitized the Brummer Gallery Records, now available online on the museum’s Thomas J. Watson Library website; see Digital Collections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brummer Gallery Records, http://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p16028coll9. Catalog cards recording purchase and sale information show that the mosaic was owned once under the number P4136 and once as N5207. The Hearst estate sold the mosaic in 1941 at the Hammer Galleries, New York, lot 563. ↩

-

The Brummer estate sold it in 1949 at Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, lot 863. ↩

-

Fragment no. 62.AH.2.13. ↩

-

According to Lancha, who dates the mosaic to AD 150–200; see Lancha 1981, 229–32, no. 373. ↩

-

Lancha identifies the birds as a partridge, a duck, a pheasant, and a magpie; see Lancha 1981, 230. ↩

-

For an in-depth examination of the image of Orpheus in Roman mosaics, see Jesnick 1997. ↩

-

For a general discussion of the multiple decor style, see Dunbabin 1999, 74–76, with additional references. ↩

-

Although the original catalog card for Brummer Archive number P4136 does not appear in the online collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, supplemental material linked to the record includes a hand-drawn plan of the excavations that indicates the locations of the mosaics. Henri Stern, in his summary of the history of the mosaics, records that the original architectural plan, now lost, was made by the architect M. Rambaud; see Stern 1971, 124. ↩

-

Vassy and Guy 1913, 628–32; and Lafaye 1909, nos. 219, 220, 221. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, no. 220; Vassy and Guy 1913, 631; Stern 1971, fig. 1; and Lancha 1981, 232–36, plates 128–30 (images of the mosaic before restoration), no. 374, which dates the mosaic to AD 150–200. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, no. 221; Vassy and Guy 1913, 629–31; Stern 1971, fig. 12; and Lancha 1981, 236–39, plate 131, no. 375, dated to AD 150–175. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, nos. 222,1 and 2, 223, 224; Vassy and Guy 1913, 628–32. According to Vassy and Guy, a poorly preserved mosaic decorating the floor of the corridor, featuring a “simple Greek” design, was left in situ at this time. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, no. 224; Vassy and Guy 1918, 628; and Lancha 1981, 241–44, plates 132–33, no. 380, dated to AD 175–200, now in the Musée Gallo-Romain de Saint-Romain-en-Gal. Hylas, who sailed with Herakles and the Argonauts, was carried off by nymphs when drawing water from a spring (as in the version by Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 1.1207–1239). Although the subject of Hylas and the Nymphs was frequently depicted in Roman art, this is the only known example from Gaul. ↩

-

Birds on amphora: Lafaye 1909, no. 222,1; and Lancha 1981, 244–45, plate 124a, no. 381 (Musée de Grenoble). Rectilinear pattern: Lafaye 1909, no. 222,2; and Lancha 1981, 245, plate 124b, no. 382 (Musée de Grenoble). Female head: Lafaye 1909, no. 223; and Lancha 1981, 246–48, plate 135, no. 383 (Musées de Vienne). ↩

-

For a similar composition, see Lafaye 1909, no. 217. Found in 1894 in Sainte-Colombe, this design also consists of a square emblema with a honeycomb pattern set within a geometric background, but an image of Venus is in the center. This mosaic was originally identified as the Orpheus mosaic in the Getty Museum; the report by M. Stothart on this misidentification is published in Stern 1971, 131–33. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, no. 201 (repeated as no. 242); Stern 1955, 68–69, no. 4; Stern 1971, 138, fig. 15, a reconstruction of the mosaic, which was discovered in 1822 in a vineyard in Montant and then destroyed in a fire in 1968; and Lancha 1981, 226–29, plates 124–25, no. 372, which dates the mosaic to the early third century AD. ↩

-

Lafaye 1909, no. 181 (repeated as no. 233); Stern 1955, 69, no. 6; and Lancha 1981, 89–93, plates 34–37, no. 282, which dates the mosaic to the end of the second century AD. The mosaic was found in 1859 in the southeast corner of the Campus Martius. ↩

-

See Stern 1955, 68–77, for a catalogue of forty-seven mosaic floors from all areas of the Roman Empire with the subject of Orpheus and the animals. (The Getty mosaic is no. 5.) ↩

-

Stern 1955, 70, no. 15, with additional references, dates the mosaic to no later than the second century AD. Stern includes two other variants on the type, with Orpheus completely separated from the animals; see Stern 1955, 73–74, no. 28 (La Chebba, Tunisia) and no. 32 (Tanger, Algeria). ↩

-

Foucher 1960a, 8–11, plates 1, 2, end of the second century AD, from the Bir Zid district. ↩

-

Slim 1987, 210–11, no. 78 (now in the El Djem Archaeological Museum), late second or early third century AD. ↩

-

See Stern 1971, fig. 10 (photograph no. 1454 in the archives of the Musées de Vienne), probably taken in 1912, when the mosaic was uncovered for the second time. ↩

-

Vassy and Guy 1913, 631, specify that of the three mosaics removed, the Orpheus was reinforced with cement to preserve it for future examination. ↩