14. Commode

- French (Paris), early to mid-1750s

- Attributed to Joseph Baumhauer (French, died 1772; ébéniste privilégié du Roi, ca. 1749)

- White oak veneered with ebony* and a wood identified as service tree*, set with panels of Japanese lacquer on Japanese arborvitae and painted with European lacquer; drawers of white oak; brass and iron hardware and lock; gilt bronze mounts; campan mélange vert marble top

- H: 2 ft. 10 3/4 in., W: 4 ft. 9 1/2 in., D: 2 ft. 3/4 in. (88.3 × 146.1 × 62.6 cm)

- 55.DA.2

Description

The commode has a serpentine front and sides and is raised on four five-sided legs. The entire body of the commode is occupied by two drawers. The upper drawer is fitted with a lock that shoots a bolt that engages with the drawer below. The commode is topped by a slab of campan mélange vert marble, which is cut to conforming shape and edged with moldings above and on its underside.

The corner mounts are composed of foliate scrolls overlaid with a branch of flowers and buds emerging and rising from a calyx. The latter is backed by a whorl of leaves, from which descends a pendant of leaves and berries along the outer edge of the convex scrolled shaft of the mount. A cluster of a flower and three leaves flanks the mount in the area of the calyx. A broad molding extends down the outer edge of the leg to the foot, which is composed of concave and convex foliate scrolls.

The fronts of the drawers are outlined by a broad frame composed of C- and S-foliate scrolls. At the sides and along the top branches carrying leaves, flowers and berries emerge and twine above and below the frame, forming handles above. The central frame, forming a tripartite front, is similarly composed, with leafy branches extending to either side at the base to form handles for the lower drawer. At the upper part of this frame the keyhole pierces a leaf that grows from a short branch that is tied with a crinkled ribbon. The branch is also clasped by foliate C-scrolls at either side, which rise to flank a fanlike arrangement above.

The apron mount, attached to the base of the lower drawer, is composed of a leafy calyx set between two C-scrolls from which extend five leafy branches carrying berries. The lower profile of the front is framed by leafy scrolls that extend, as plain moldings, down the inner edges of the legs. At the junction of each leg with the body of the commode small branches of leaves and berries extend from the leafy frame. The sides are similarly framed, with a leafy cabochon set over the frame at the center of the top and the base. The molding that outlines the lower profile of the commode is centered by a single scrolled leaf. At the junction of the legs with the body a similar small branch of leaves and berries extend from the molding.

The front is veneered with two lacquer panels, the joint between them hidden by the right edge of the central framing mount. A larger panel, covering the left two-thirds of the commode front, shows a rocky shoreline with flowering plants at the left and two waterfowl, aligned at the center of the commode, at the right. Their feet and beaks are painted red, and their plumage is golden. Above, flanking the keyhole escutcheon, two butterflies, painted in gold, were added by a French vernisseur.

A smaller panel, covering the right third of the commode, shows a rocky shoreline from which grow flowering hibiscus trees and carnations. The flowers and some of the leaves on both panels are painted red. The gold-speckled ground is painted with small groups of flowering plants and grass in gold, while waves are represented in the foreground.

The left side of the commode is set with a panel of Japanese lacquer showing a hillock topped by a group of chrysanthemums and grasses (fig. 14-1). At the center front, a lower hillock is topped with grasses. The hillocks and the majority of the flowers and leaves are depicted with gold-sprinkled reddish lacquer. Two leaves and one flower are cream colored. All the petals and leaves are outlined in gold, and the veins of the leaves are similarly portrayed. The foreground is painted with waves. The right side of the commode is set with a panel of Japanese lacquer showing a basket containing hibiscus flowers and leaves and a rising branch of wisteria. The basket is fitted with a tall, rectangular handle. The remaining area of the surface of the commode and the outer surfaces of the legs are painted with imitation nashiji (See “Technical Description” below).

Marks

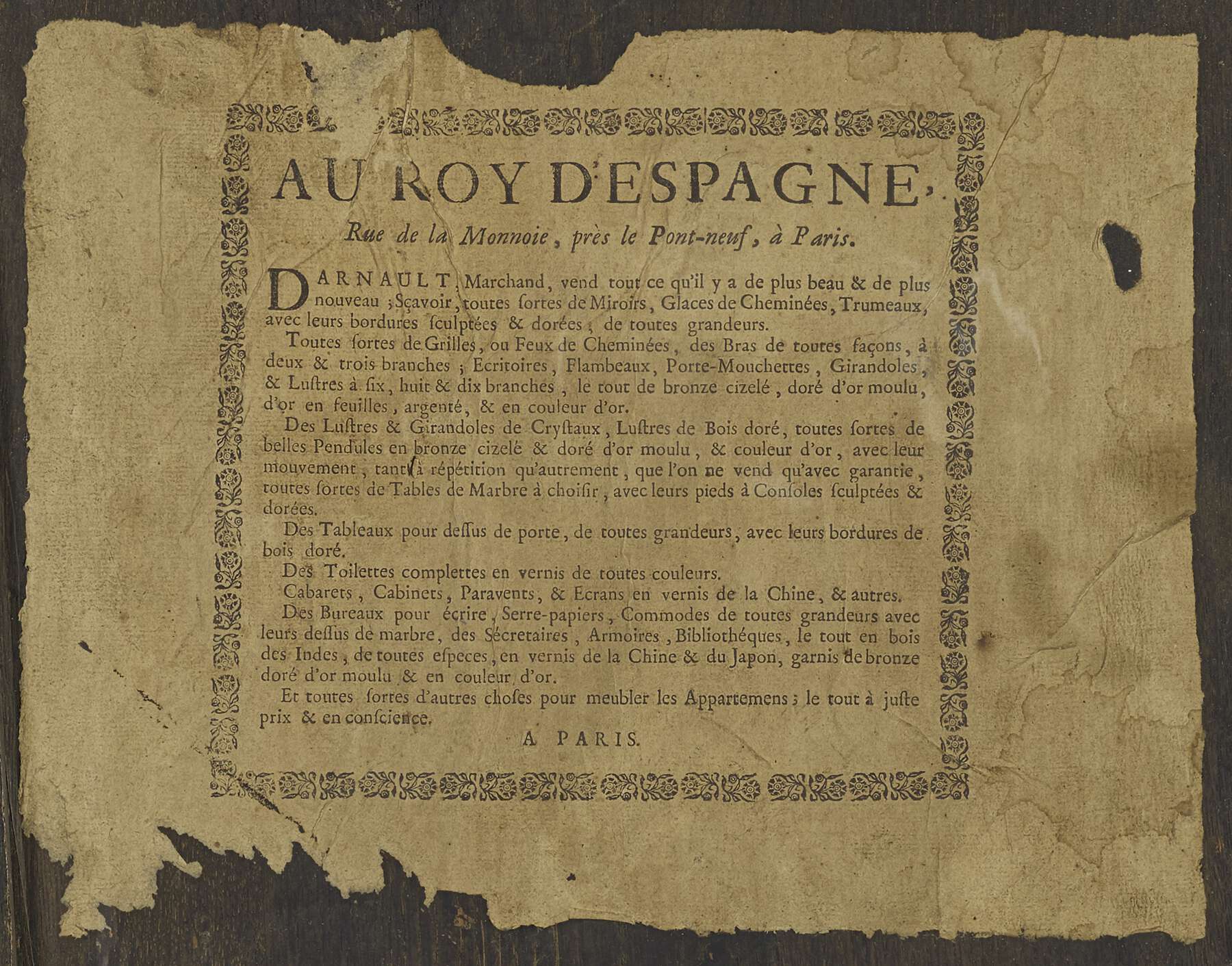

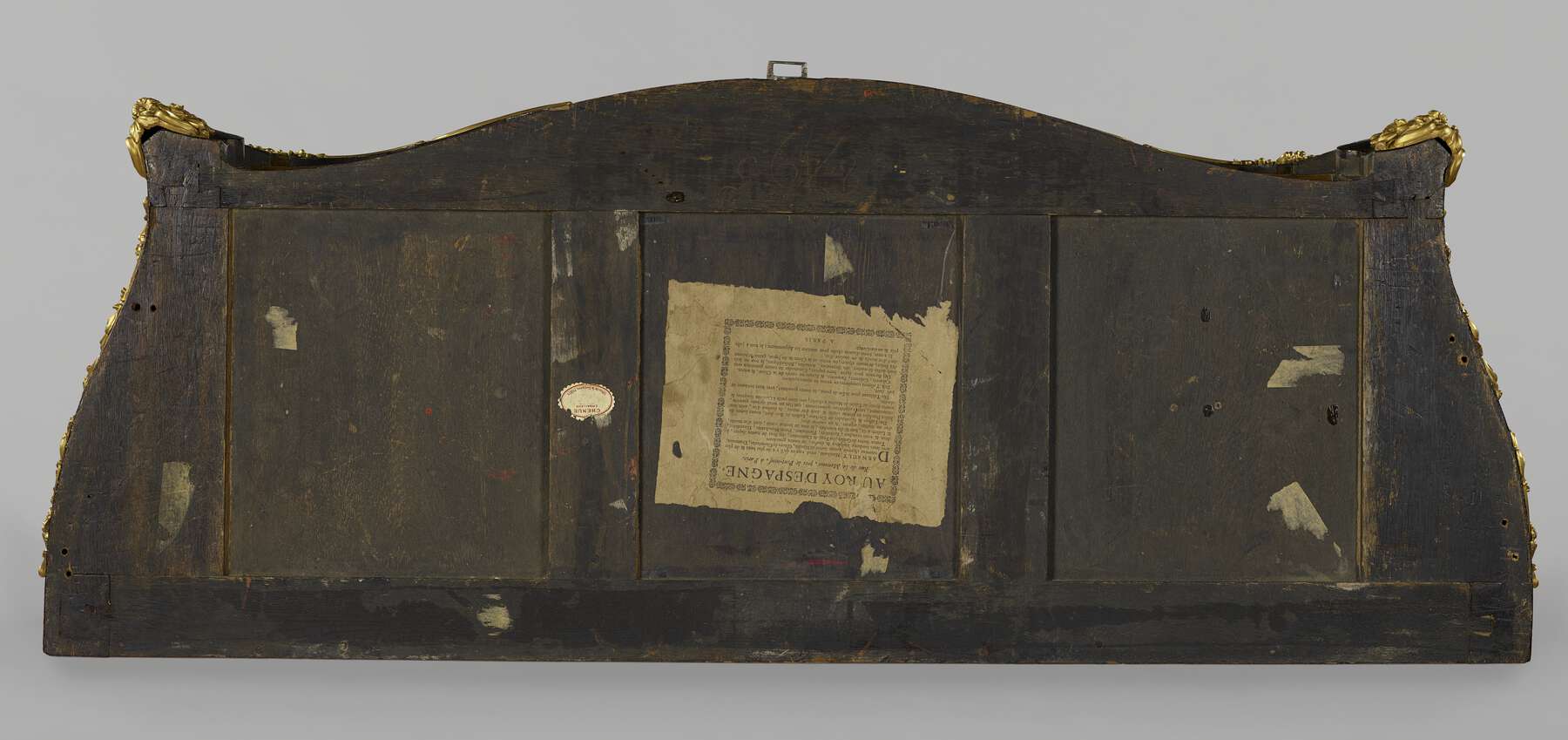

A paper trade label of the marchand-mercier François Darnault, or François Charles Darnault, is pasted on the top of the carcass, and another is pasted underneath (fig. 14-2). Each reads as follows:

AU ROY D’ESPAGNE,

Rue de la Monnoie, près le Pont-neuf, à Paris.

DARNAULT, marchand, vend tout ce qu’il y a de plus beau & de plus nouveau, sçavoir, toutes sortes de miroirs, glaces de cheminées, trumeaux, avec leurs bordures sculptées & dorées, de toutes grandeurs.

Toutes sortes de grilles, ou feux de cheminées, des bras de toutes façons, à deux & trois branches; écritoires, flambeaux, porte-mouchettes, girandoles & lustres à six, huit & dix branches, le tout de bronze cizelé, doré d’or moulu, d’or en feuilles, argenté, & en couleur d’or.

Des lustres & girandoles de crystaux, lustres de bois doré, toutes sortes de belles pendules en bronze cizelé & doré d’or moulu, & couleur d’or, avec leur mouvement, tant à répétition qu’autrement, que l’on ne vend qu’avec garantie, toutes sortes de tables de marbre à choisir, avec leurs pieds à consoles sculptées & dorées.

Des tableaux pour dessus de porte, de toutes grandeurs, avec leurs bordures de bois doré.

Des toilettes complettes en vernis de toutes couleurs.

Cabarets, cabinets, paravents, & écrans en vernis de la Chine, & autres.

Des bureaux pour écrire, serre-papiers, commodes de toutes grandeurs avec leurs dessus de marbre, des secrétaires, armoires, bibliothèques, le tout en bois des Indes, de toutes espèces, en vernis de la Chine & du Japon, garnis de bronze doré d’or moulu & en couleur d’or.

Et toutes sortes d’autres choses pour meubler les appartemens; le tout à juste prix & en conscience.

A PARIS.

Figure 14-2

Figure 14-2A small oval paper label is attached to the upper surface of the commode. It is printed in red, “CHENUE/ EMBALLEUR/ 5 rue de la Terrace, PARIS,” and inscribed in pencil, “Michel” (see fig. 14-6). The top of the carcass is inscribed in red crayon, “8795.”

Commentary

The commode is not stamped with the maker’s name, “JOSEPH,” which was used by Joseph Baumhauer.1 However, it is attributed to this maker because at least six other commodes, four of which bear his mark, exist with almost precisely the same size and form and carry mounts of the same models.

1. A stamped commode veneered with panels of black and gold Japanese lacquer depicting rocky landscapes with villages, in the Jones Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (fig. 14-3).2

2. A pair of stamped commodes veneered with bois de bout marquetry in the Widener Collection at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.3

3. A stamped commode veneered with bois de bout marquetry in the Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio.4

4. An attributed commode veneered with wave-cut marquetry in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor.5

5. An attributed commode decorated with European lacquer in the Budapest Museum of Applied Arts, Hungary.6

Figure 14-3

Figure 14-3The attribution of this commode to Joseph Baumhauer (known simply as Joseph in his time) is further strengthened by the appearance of mounts of the same model on various pieces of furniture stamped or attributed to this master. The elaborate apron mount is found on an attributed commode in the musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, which is veneered with bois de bout marquetry.7 Corner mounts of the same model appear on a curved and stamped bureau plat in the Wrightsman collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,8 and on an apparently unstamped commode sold from the collection of Cécile Sorel in 1928. The latter also bore sabots of the same model.9 The center of the upper part of the framing mount that encloses the escutcheon is found in a similar position on a pupitre à écrire delivered to Count Johann Karl Philipp von Cobenzl, minister plenipotentiary of the Austrian Netherlands, by Lazare Duvaux in 1758.10 Here the mount is without the overlaid leafy branch tied with a ribbon bow.

The Museum’s commode bears two trade labels of the marchand-mercier François Darnault, or François Charles Darnault, pasted above and below the carcass, giving the name of the shop as Au Roy d’Espagne in the rue de la Monnaie. Darnault had moved to this address from his establishment A la Ville de Versailles in the rue Grenier in 1745, leaving his son François Charles in charge of the original business. In 1753 the son moved to the more fashionable establishment and formed a partnership with his father, who died shortly after.11 The label is undated and does not help to date the commode, which, on stylistic grounds, must have been made in the early to mid-1750s and was probably ordered by François Darnault. The marchand-mercier would have supplied the four Japanese lacquer panels that decorate the front and sides of the commode. Two panels form the front, and the seam is hidden by one of the vertical mounts of the inner frame. Two panels of Japanese lacquer of different sizes have been used here by French craftsmen to create a symmetrical composition out of panels that were originally asymmetrical. The Parisian ébénistes used disparate panels of Japanese lacquer to create symmetrical compositions, often of tripartite composition.

At some point, the original black field turned brown and was painted over, quite crudely, with black varnish. This may have been done at the time of the construction of the commode. As was quite common, a French vernisseur may have added some flying insects and extraneous tufts of grass to the front panels, both to hide small areas of damage and, perhaps, to fill the empty areas of the Japanese composition, so alien to European taste.12 The imitation nashiji lacquer found on all the surfaces of the commode not covered with Japanese lacquer is an added refinement that is also found on the works of Baumhauer’s contemporary Jacques Dubois.13 Unfortunately, it appears to have been repainted at least twice. The surface now visible consists of a low-quality varnish with suspended coarse copper flakes. It must have originally been quite bright and sparkling, giving the commode an extra air of luxuriance, in combination with its richly gilt mounts and the fine top of green campan mélange marble, the edge of which is carved with the unusual feature of a double molding above and below.

Provenance

–1955: Sir Alfred Chester Beatty, American, 1875–1968 (London, England), sold through Sir Robert Henry Edward Abdy, fifth Bart., English, 1896–1976, to J. Paul Getty, 1955;14 1955–76: J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, upon his death, held in trust by the estate; 1976–78: Estate of J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, distributed to the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Bibliography

, n.p., ill. facing p. 336; , 135 n. 30; , 81; , 114–15; , 85; , 144–45, ill.; , vol. 1, 152; , 106; , 36; , 452; , 233, 244, no. 236; , 27, no. 29; , 171, pl. 2; , 171, fig. 78; , 16–17, no. 29; , n.p., color pl. 56; , 93–94, 95, figs. 2, 6; , 151–53, fig. 2; , 80–87, 81, fig. 25.

- G.W.

Technical Description

The carcass of the commode is made entirely of flat-sawn white oak (fig. 14-4). The four corner posts run from the floor to the top of the case and are formed of single pieces of wood. Each of the side panels is made of two boards, butt joined, with their grain running horizontally. The upper board on each side is exceptionally wide, measuring almost 40 cm across the grain, while the lower board is much narrower, at approximately 8 cm. The side panels are flat on the interior and shaped in a gentle curve on the exterior. They are approximately 3 cm thick at their widest point and are attached to the front and rear posts with tongue-and-groove joints.

The case back is made using tripartite frame-and-panel construction (fig. 14-5). The horizontal rails attach directly to the rear legs with unpinned mortise-and-tenon joints (nowhere on the case are mortise-and-tenon joints pinned). The upper rail is made of two pieces of wood, one glued atop the other. The upper piece is only a narrow spline of just over 1 cm thickness; this kind of composite rail is anomalous and might be the consequence of an initial measurement error by the cabinetmaker. It is a feature that is not duplicated in the otherwise similar construction of commodes by Joseph Baumhauer at the Victoria and Albert Museum (1013-1882) or the Legion of Honor (1931.112). The three equally sized panels of the back are each made of two boards, butt joined and chamfered on the interior edges, with the grain of the wood running vertically.

The case top is also a tripartite frame-and-panel assembly with equally sized panels, each made from two butt-joined boards arranged with the grain running from front to back; these are also chamfered on their interior edges. The four perimeter rails are attached to the corner posts with single, open-faced dovetails (fig. 14-6). The side rails extend slightly to the inside of the front posts, allowing their lower surfaces to act as “kickers” for the drawer below. The rear rail of the top overlaps the case back assembly and is attached to it with three oak dowels that run downward through the former and into the latter. The medial rails are joined at front and back with unpinned mortise-and-tenon joints.

Figure 14-6

Figure 14-6The case bottom and the dustboard (separating the two drawers) are assembled in a nearly identical fashion, each being a modified tripartite frame-and-panel construction without side rails. The rear rails are set loosely into square-shouldered dadoes in the rear posts. The front rails are attached to the corner posts with horizontal sliding dovetails whose mortises run through the entire thickness of the posts. As usual, the medial rails are joined at front and back with mortise-and-tenon joints. The panels are each made of two or three butt-joined boards, the grain oriented front to back, with edges chamfered on the lower surfaces. As there are no side rails in either the case bottom or the dustboard, the side panels of these assemblies run all the way to the angled sides of the case. These irregularly shaped panels are supported along their front, back, and inner edges in the usual fashion, in grooves cut in the rails. Along their outer edges where they meet the case sides, the panels are completely unsupported. The four internal drawer guides are each made of a single piece of oak, cut to an L-shaped section and glued down onto these side panels. In addition, thin strips of oak are glued to the underside of the side panels of the dustboard, just opposite the guides, to serve as kickers for the lower drawer.

The curved lower edge of the case front and sides runs below the rails of the case bottom; numerous short blocks of oak have simply been glued to the bottom of the rails, the upper portions of the legs, and the bottom of the lower drawer front (fig. 14-7). These were then sawn, rasped, and filed to shape in order to create the desired profile.

The drawer fronts are made in a laminated construction with four rows of upright boards stacked and glued edge to edge to make up the full height of the element. Some rows are composed of single boards, while others contain as many as seven short blocks of wood along their length. The upper edges of both drawer fronts, as well as the lower edge of the upper drawer front, are veneered with ebony. The sides and backs of the drawers are made of single boards and have slightly rounded top edges; they are assembled using standard through-dovetails at the rear and half-blind dovetails at the front. The front dovetails are hidden by curved blocks of wood glued over them to serve as extensions to the drawer fronts (fig. 14-8). The front legs have been rebated along their front edges to accommodate these drawer front extensions. The drawer bottoms are each made of five thin boards, butt joined, with the grain running front to back. They are set into rebates in the bottom of the drawer sides and back, and the joints are covered with a thin strip of oak that serves as the drawer runner.

Wherever Japanese lacquer is not present, the exterior of the commode has been veneered with a wood identified as belonging to the Maloideae subfamily of the Rosaceae. Based on its microscopic and macroscopic features, this wood is likely to be service tree (Sorbus domestica; cormier in French) but could also be pear or perhaps apple.15 All three woods have very smooth grain and were readily available to Parisian cabinetmakers of the period at relatively low cost.16 This veneer has been applied with the grain oriented vertically rather than on the diagonal as was more common.

The commode has one large double-throw lock in the upper drawer that has two bolts operated by a single key. The first bolt rises into the case top, and the second drops simultaneously down through a strike plate (attached to the dust panel) and into the lower drawer front, thus securing both drawers.

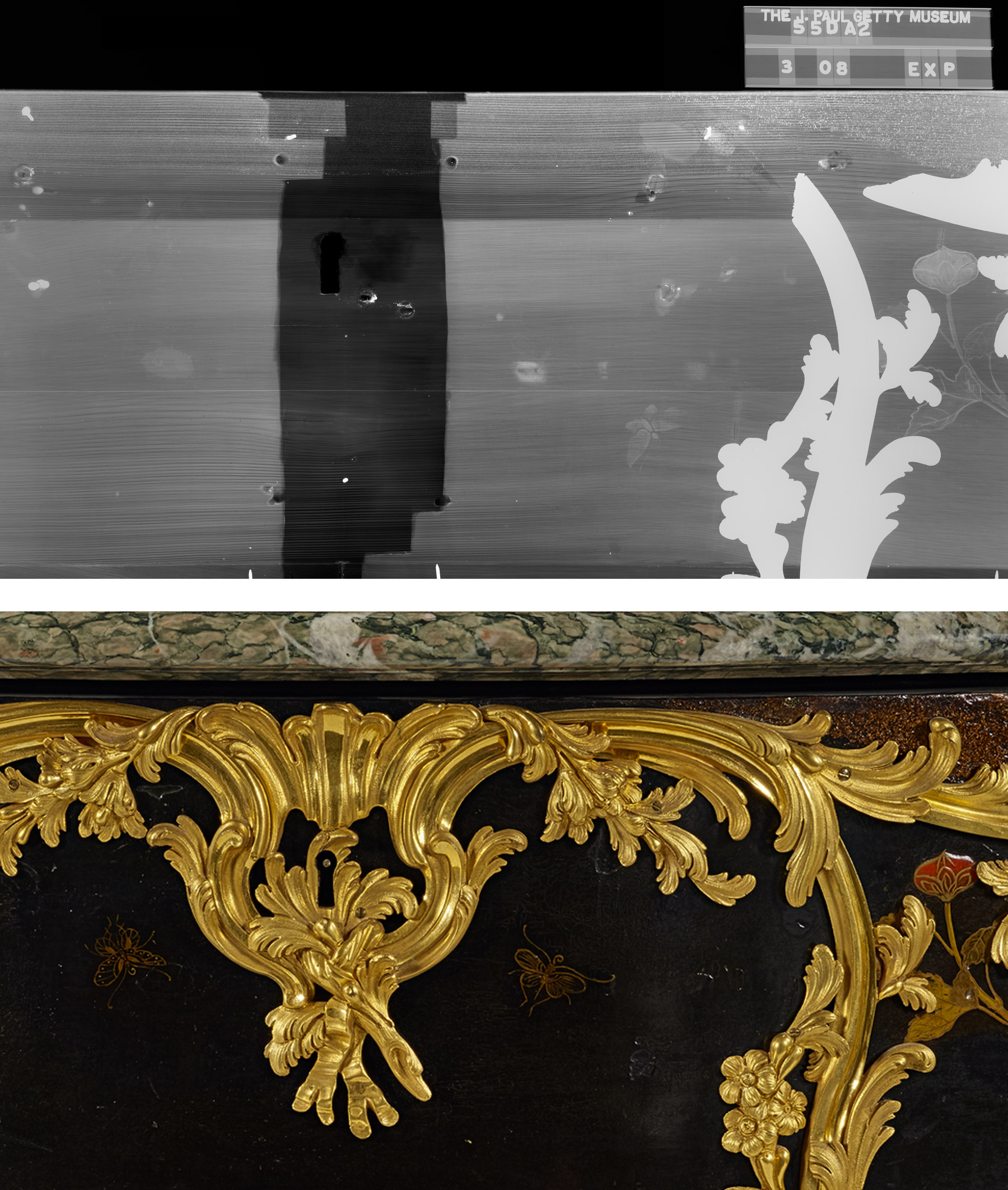

The commode features panels of Japanese lacquer that have been applied to the drawer fronts and to the sides of the case. On the drawer fronts, two separate panels of raised (or takamakie) lacquer have been arranged in an unusual manner to create a very symmetrical composition out of panels that were originally asymmetrical. X-radiography clearly shows that the first panel covers the left two-thirds of the drawer fronts, with floral designs on the left and ducks and butterflies on the right. The second panel, half the size of the first, covers the right third of the drawer fronts (fig. 14-9).

Figure 14-9

Figure 14-9The panels on the front of the commode were almost certainly taken from the tops of a matched pair of Japanese cabinets dating to the second half of the seventeenth century. The larger panel on the left of the Museum’s commode would have been nearly the entire top of one of the cabinets, while the panel on the right was only one-half of the top of the matching cabinet (whose decoration would have been a near mirror image of the first).17 The unused half of the second cabinet’s top panel would likely also have had a pair of birds. The current whereabouts of this half-panel are unknown, but it is intriguing to imagine that Darnault may have saved it for use in another, subsequent, commission. Pairs of preserved Japanese cabinets showing very similar compositions and with appropriate dimensions are at Temple Newsam (fig. 14-10) and Christie’s lot 272, sale 5538, December 16, 2008, in Paris. Lacquerwork that is extremely similar in technique and design to the Getty’s commode (perhaps even from the same workshop) can be found applied to the lower half of a nineteenth-century French secrétaire, also at Temple Newsam (fig. 14-11).

Figure 14-10

Figure 14-10 Figure 14-11

Figure 14-11The two panels on the sides of the commode are also Japanese lacquer, though they are unrelated in style or technique to each other or to the panels on the front. These panels are cut to shape so that the seams between the panels and the French aventurine surrounding them are hidden behind the gilded bronze mounts. Both panels are decorated in flat (or hiramakie) style lacquer whose size and compositions suggest that they might have come from the interior surfaces of cabinet doors. The panel on the right is a fine example of so-called kodaiji-style decoration in which gold leaves with black veins are juxtaposed with black leaves with gold veins.

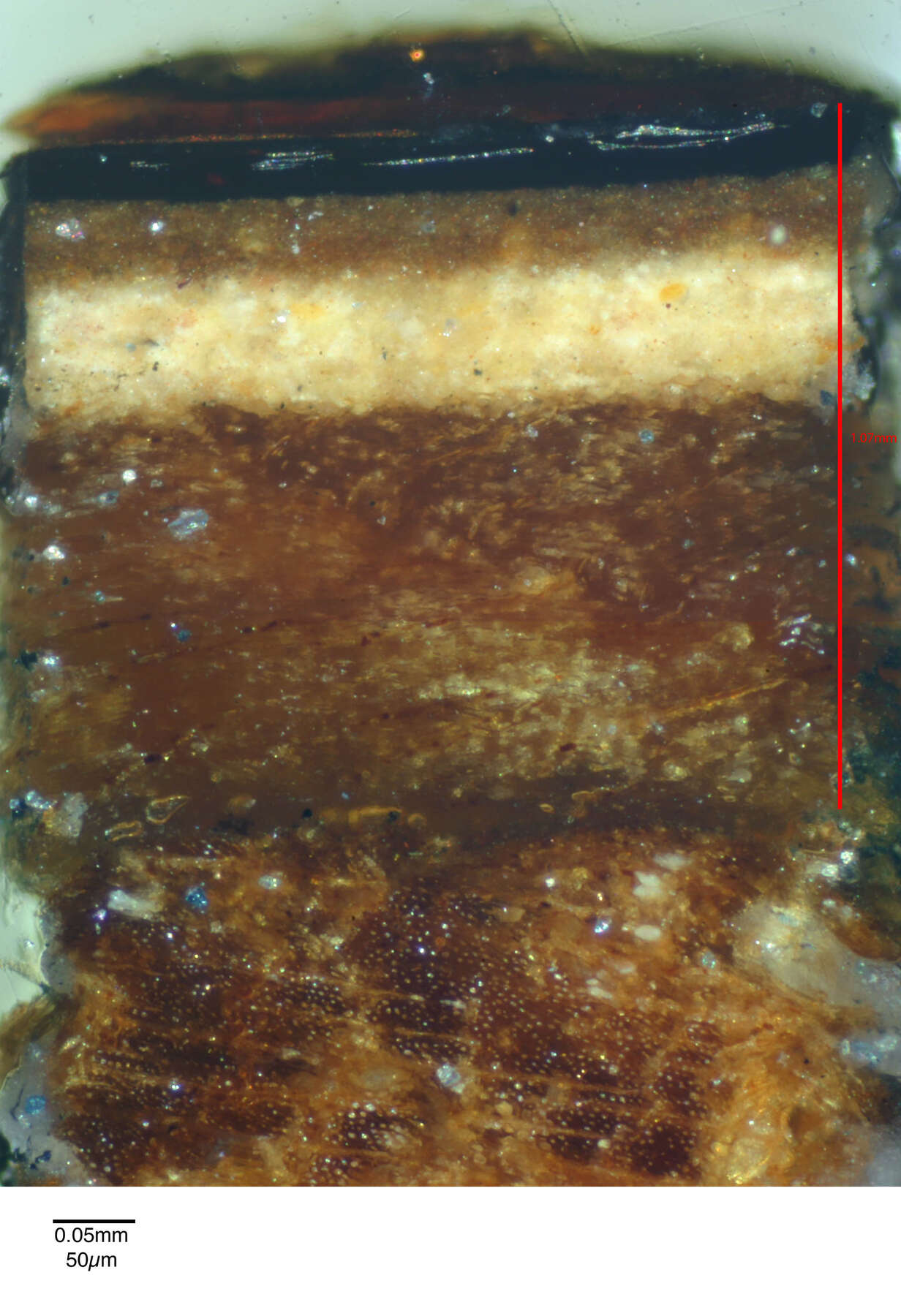

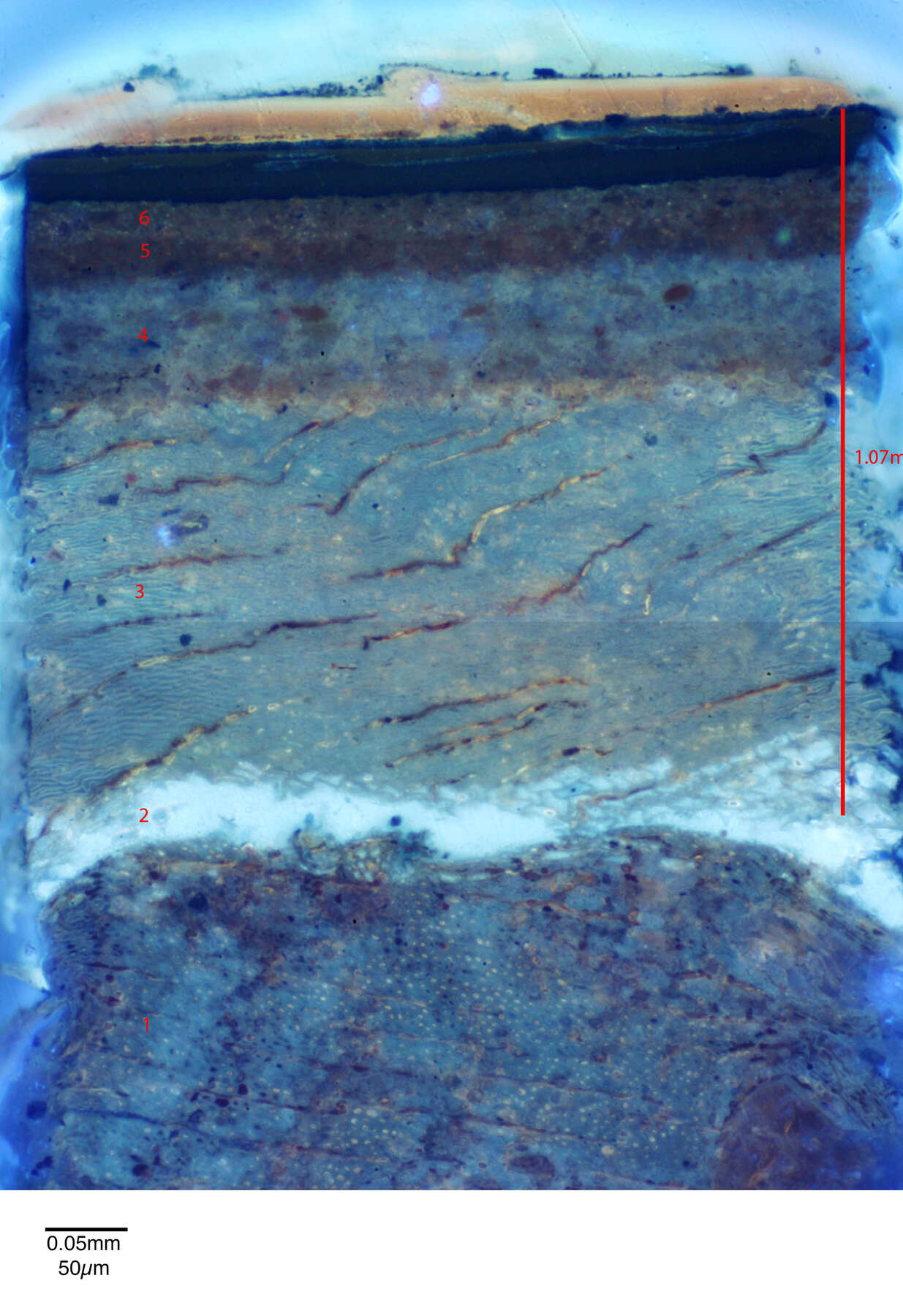

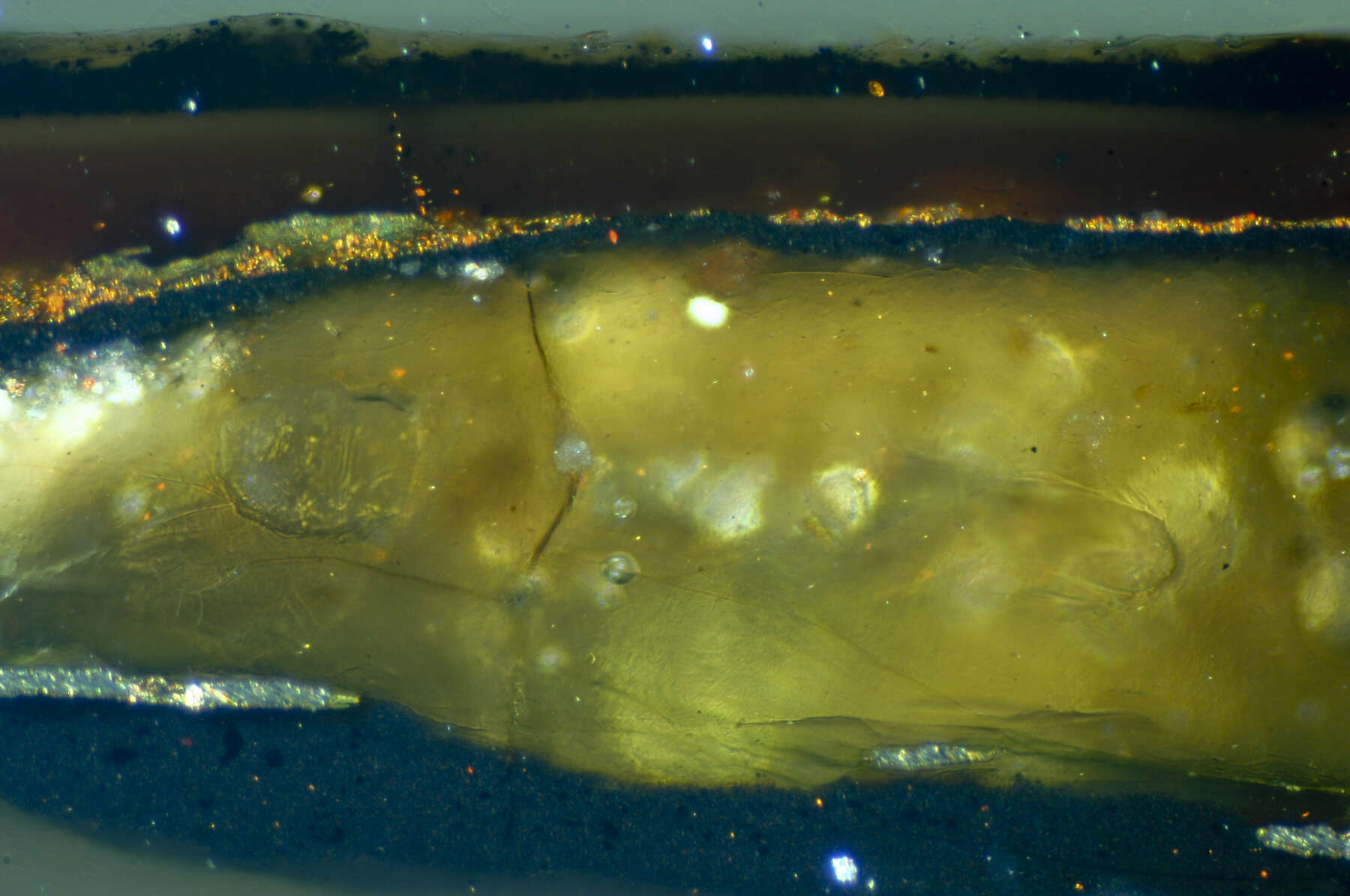

Based on cross-section samples taken from the front left panel, the Japanese lacquer on this commode was planed and scraped by the French craftsmen to approximately 1.1 mm in thickness; this includes both the lacquer itself and the bare half-millimeter of the original Japanese wood substrate that the French cabinetmaker left behind (figs. 14-12, 14-13).18 This Japanese wood has been identified microscopically as Japanese arborvitae (Thuja standishii).

Figure 14-12

Figure 14-12 Figure 14-13

Figure 14-13It is unusual that the Japanese lacquer panels on the drawer fronts extend beyond the boundaries of the gilded bronze frames, clear to the edges of the drawer fronts (see fig. 14-9). X-radiography reveals that the original Japanese nashiji, or sprinkled metal flake, border surrounding the compositions is still present, though hidden, along the top edges of the panels (fig. 14-14). This border is linear (in keeping with the rectangular format of the original cabinet) and is unrelated to the curving outline of the present mounts. Scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) on cross-section samples shows that the original border was executed in silver metal flake, common in Japanese work of the period.19

Figure 14-14

Figure 14-14A detailed analysis was conducted on the Japanese lacquer from the drawer fronts using SEM-EDS, fluorescence microscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (py/GC-MS). The foundation for the lacquer consists of three layers of predominantly clay-based material, with the lowermost layer bound in glue and the upper two foundation layers bound in thitsi lacquer with the addition of drying oil and starch. A small number of compounds associated with cedar oil were also found in low abundance in the foundation layers. While this could indicate that cedar oil, collected from a wide range of trees in the family Cupressaceae, was used in the foundation, this material is not normally associated with Japanese lacquer and the compounds are more likely to be associated with volatiles from the substrate wood, Thuja standishii, a member of the same botanical family. Above the ground, a thin layer of carbon black was applied, followed by two layers of dark-colored, transparent lacquer. The hiramakie and nashiji decoration was applied over this black lacquer ground in a manner similar to that seen on the B.V.R.B. commode, using gold, silver, and vermilion (see cat. no. 5). Also, similar to the B.V.R.B. commode, the raw lacquer used to prepare these panels is not entirely true Japanese urushi but also contains thitsi, or Burmese lacquer, an inferior but significantly less expensive alternative. Thitsi alone appears to have been used in the foundation layers, while the upper layers consist of a combination of thitsi and urushi. In all cases the lacquer has been further mixed with a drying oil, a class of materials commonly added to both extend the expensive lacquer and modify its working properties.

After the lacquer panels were thinned and glued into their current configuration, the French vernisseur painted over the linear Japanese nashiji border with black and supplanted it with his own imitation of nashiji (known as aventurine in eighteenth-century France),20 which conformed to the curved gilded bronze mounts and also covered the legs. X-radiography reveals that in addition to painting out the border, the vernisseur painted over an original gold butterfly on the upper drawer (fig. 14-14). The butterfly appears to be slightly damaged in the X-ray, and this may have been the reason that it was covered. The French craftsman then added two butterflies to the upper drawer, placing them on either side of the central escutcheon as if to reinforce the contrived symmetry of the overall composition. These added butterflies were added in brass powder rather than gold.

Analysis of the original French aventurine by SEM-EDX and py/GC-MS shows that it is composed of four major layers (fig. 14-15). First, a black ground coat of carbon black mixed with bone black pigment bound in a spirit-resin varnish was applied. This resin mixture shares many characteristics of traditional eighteenth-century transparent spirit varnishes, including the use of the hard resins sandarac and shellac21 to improve polishing, and softer resins from the Pine family, along with camphor to plasticize and toughen the final film. Above the pigmented varnish layer, a thin size, of unknown organic composition, was applied. This size served to adhere fine brass flakes, which were then covered with a thick varnish layer similar to that used in the black ground.

Figure 14-15

Figure 14-15The aventurine visible today is not original to the commode; cross-section microscopy clearly reveals that there have been at least two complete reapplications of the aventurine. Analysis of the first major restoration shows that it used a ground containing bone black pigment mixed with indigo, bound in a spirit-resin varnish containing shellac, sandarac, and a small amount of drying oil. The indigo would have served to impart a cooler, deeper black and counteract the warm color of the shellac-containing varnish. A size containing vermilion was used to adhere the brass flakes on top of the black ground. The pigmented layer and the metallic decoration were coated with a transparent varnish of a very similar resin composition, although with the addition of slightly more drying oil. This restoration varnish appears to be primarily drying oil with the addition of shellac and polycommunic diterpenoid resin, likely sandarac or soft copal. The more recent restoration (visible today) uses inappropriately coarse copper flakes in an oil-resin varnish that has badly reticulated. This varnish contains a mixture of a large amount of drying oil with shellac and “hard” copal. This restoration layer most likely dates to the nineteenth century or later, when hard copal from Africa was widely used as varnish material.22 The cross-section analysis suggests that the original French aventurine may only survive in a fragmentary state.

In addition to the repainting of the French aventurine, there has been considerable restoration to the Japanese lacquer panels. Much of the gold decoration on the front and left side panels has been overpainted in the course of at least two significant restoration campaigns. This can be observed both under ultraviolet illumination (fig. 14-16) and by comparison of X-radiographs with visible light images (fig. 14-17). In strong light, it is also possible to see that the original black background of the panels has faded considerably to brown and that, to remedy this, some considerable areas have been “reinforced” with washes of black varnish. The browning of light-aged Asian black lacquer is a common occurrence when it is exposed to heat and humidity,23 as it certainly would have been when it was glued to the drawer fronts by the French cabinetmaker. The kodaiji-style panel on the right side remains in very good condition and is the least restored.

Figure 14-16

Figure 14-16 Figure 14-17

Figure 14-17The gilded bronze mounts are very skillfully finished and fitted. The foliate elements are chased in a relatively uniform and regular manner, yielding a lively, textured surface. This contrasts with the smooth surfaces of the moldings and C-scrolls, which, in turn, have alternating passages of burnished and matte gilding. The primary framing elements of the mounts are quite large, often composed of several individual castings that have been soldered together; numerous smaller elements of foliage are neatly and precisely fitted over and around these framing elements.

Ten representative gilded bronze mounts were removed from the commode and analyzed for bulk alloy composition by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). All of the analyzed mounts were found to have compositions very typical of known eighteenth-century castings; they contain about 18–22% zinc, 1–1.5% tin, and 1.5–2.5% lead, with detectable levels of impurities such as iron, nickel, silver, and antimony. The lock, lock plates, and soldering metal used to assemble the larger mounts were also analyzed and found to have normal eighteenth-century compositions for their types; both contain about 28 to 32% zinc, along with minor elements and impurities.24

It appears that all of the mounts have been regilded, at least in part by electroplating. Three pieces of evidence support this supposition. First, the gilding on the mounts is conspicuously free of any “holidays,” or small areas, often only visible under magnification, where the gold failed to adhere to the metal. Such perfect coverage of gold is much easier to achieve with electroplating than with mercury-amalgam gilding. Second, virtually all of the backs of the mounts bear traces of a dark material that may be a stopping-off varnish used to prevent gold from depositing onto the backs of mounts when they are dipped into the plating solution.25 Analysis of this varnish by FTIR and py/GC-MS has determined that the stopping-off varnish is composed primarily of bitumen, with the addition of some camphor. The third piece of evidence to suggest that the mounts have been regilded is the presence, despite the stopping-off varnish, of a small amount of gold evenly distributed overall on the backs of the commode’s mounts. Although not visible to the naked eye, this gold is easily detectable by XRF. The occurrence of an extremely thin overall gold layer on the reverse is almost never encountered with purely amalgam gilt mounts.

In addition to having been regilded, the mounts appear to have been chemically toned. The color of the mounts is considerably warmer than usual and is similar to the tonality that can be achieved using a solution of caustic soda (sodium hydroxide).

The commode’s marble top is an amygdaloidal marble called ribboned campan, or campan mélange vert, that comes from the Hautes-Pyrénées region of France. The characteristic lenticular nodules of gray-green to pinkish marl (calcareous clay) encase small nautiloids and Clymenia ammonite shells. The dark green matrix is colored by chlorite, and the broad red streaks are believed to have been caused by iron-fixing microbes in the sediment before it solidified into rock. White crystalline veins of calcite cut through the stone.

Campan marble was used as early as the first century by the Romans, who quarried it near Pont de la Taule (Ariège). The quarry at Espiadet was active through the medieval period and was declared to be a royal quarry by Louis XIV. It was very active in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and was closed in the twentieth century.

- A.H.,

- J.C.,

- M.S.,

- and R.S.

Notes

For information on Joseph Baumhauer, see , 82–89; , 14–45; , 230–45. ↩︎

Jones Collection, acc. no. 1013-1882; 2 ft. 10 in. x 4 ft. 2 in. x 2 ft.; see , 453. ↩︎

Acc. nos. 1942.9.411 and 1942.9.412; ex. coll. Duke of Leeds, Hornby Castle, sold, Christie, Manson & Woods, Catalogue of a Small but Choice Collection of Porcelain [ . . . ], June 28, 1901 (London: Christie, Manson & Woods, 1901), lot 100; 33 1/16 x 51 7/8 x 23 3/4 in. and 33 1/16 x 49 x 22 7/16 in. (this model of commode was made in two sizes, one slightly smaller in width than the other, with both sizes represented in this collection). See , n.p.; , fig. 47. ↩︎

Acc. 1976.38; 86 x 127 x 63 cm; ex coll. Edmund de Rothschild, Exbury. See , 38, fig. 34; , 233, fig. 234. ↩︎

Acc. no. 1926.112; 2 ft. 11 in. x 4 ft. 9 1/4 in. x 2 ft. 1 5/8 in.; ex. coll. Ascher Wertheimer, London, and Archer H. and Collis P. Huntington. See , 82, fig.1; , 130, fig. 4. ↩︎

84.5 x 139 x 58.5 cm; ex. coll. Festetics Palace at Keszthely. See , cover illus. The floral sprays that entwine the inner framing mounts are missing. The commode is reputed to be of nineteenth-century date but has not been seen by the author. ↩︎

Inv. MJAP-M 570. See , 106–9, no. 22. ↩︎

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Wrightsman, acc. no. 1979.172.2. See , vol. 2, 300–301, no. 148. ↩︎

Galerie Georges Petit, Objets d’art et très bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle et autres, December 6–7, 1928 (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1928), no. 180. ↩︎

Ex. coll. Wildenstein & Co. and Akram Ojjeh, sold, Magnifique ensemble de meubles et objets d’art français: Collection Monsieur Akram Ojjeh, June 26, 1979 (Monaco: Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1979), lot 141; , 233, fig. 235. ↩︎

, 21–23. ↩︎

For an X-ray photograph of a commode by Bernard II van Risenburgh showing European additions to the Japanese lacquer, see , 77, fig. 61. ↩︎

Jacques Dubois seems to have been the first ébéniste to have employed this technique, produced for him by vernisseurs such as the Martin brothers. It is found on a secrétaire en dos d’âne that bears crowned Cs on its mounts and belonged to Joseph-Florent, marquis de Vallière (1717–1776). See , 290–91, no. 158. The desk was sold at Christie’s, Important French Furniture from a Private Collection, May 21, 1996 (New York: Christie’s, 1996), lot 346. See also a similar desk by Dubois that is lacquered in this manner: , 288–89, no. 157. ↩︎

Correspondence between Norris Bramlett and Sir Alfred Chester Beatty, October 3, 1955, J. Paul Getty Museum Early Administrative Records, 1939, 1949–86, undated, Getty Research Institute (IA10003). On March 8, 1955, Mr. Getty paid Sir Alfred Chester Beatty an unitemized total of £27,000 for a bureau plat (55.DA.3), this commode, and a music stand by Martin Carlin (55.DA.4). In a letter to J. Paul Getty dated October 3, 1955, and mailed from Ailesbury Road in Dublin, Beatty priced the commode at £3,500, the bureau plat at £21,000, and the music stand at £2,500. ↩︎

See the Wood Identification Report by Arlen Heginbotham, dated November 24, 2008, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. Also, for a discussion of the reasons for veneering surfaces to be japanned, see cat. no. 5. ↩︎

See , 782–87. ↩︎

Another possibility is that the larger panel of lacquer came from the fall front of a “scritoire,” or writing cabinet. ↩︎

The Japanese substrate wood was identified microscopically as Thuja standeshii, or Japanese arborvitae. See the Wood Identification Report by Bruce Hoadley and Joseph Godla, dated June 26, 1995, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

See the ESEM Examination Report by Arlen Heginbotham, dated December 8, 2008, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, 4th ed. (1762), 129: “Il y a aussi une aventurine factice, qui est une composition faite avec de la poudre d’or, jetée à l’aventure sur du vernis, ou sur du verre fondu.” ↩︎

The shellac detected in the pigmented layer may relate to contamination from the size layer above rather than a material intentionally added to the resin varnish. ↩︎

Based on the presence of polyozic marker compounds detected in py/GC-MS analysis. For further discussion of the use of African copal, see , 18. ↩︎

. ↩︎

See the X-ray Fluorescence Analysis Report by Arlen Heginbotham, dated November 19, 2008, on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

A particularly early and well-preserved example of stopping-off varnish can be found on the reverse of the mounts on the Victoria and Albert Museum’s cabinet by Prignot (7247–1860), made in 1855, with mounts electroplated by Elkington’s. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Augarde 1987

- Augarde, Jean-Dominique. “1749, Joseph Baumhauer, ébéniste privilégié du Roi.” L’Estampille, no. 204 (June 1987): 15–45.

- Augerson 2011

- Augerson, Christopher. “Copal Varnishes Used on 18th- and 19th-Century Carriages.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 50, no. 1 (2011): 14–34.

- Boutemy 1965

- Boutemy, André. “L’ébéniste Joseph Baumhauer.” Connaissance des Arts 157 (March 1965): 82–89.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Getty and Le Vane 1955

- Getty, J. Paul, and Ethel Le Vane. Collector’s Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe. London: W. H. Allen, 1955.

- Getty 1963

- Getty, J. Paul. Chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection J. Paul Getty. Monaco: Jaspard, Polus et Cie, 1963.

- Getty 1965

- Getty, J. Paul. The Joys of Collecting. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1965.

- Getty 1956

- Getty, J. Paul. “Vingt mille lieues dans les musées.” Connaissance des Arts 57 (November 1956): 76–81.

- Harwood, May, and Sherman 2002

- Harwood, Buie, Bridget May, and Curt Sherman. Architecture and Interior Design through the 18th Century: An Integrated History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002.

- Heginbotham and Schilling 2011

- Heginbotham, Arlen, and Michael Schilling. “New Evidence for the Use of Southeast Asian Raw Materials in Seventeenth-Century Japanese Export Lacquer.” In East Asian Lacquer: Material Culture, Science and Conservation, edited by Shayne Rivers, Rupert Faulkner, and Boris Pretzel, 92–106. London: Archetype in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011.

- Heginbotham 2013

- Heginbotham, Arlen. “Bronzes Dorés: A Technical Approach to Examination and Authentication of French Gilt Bronze.” In French Bronze Sculpture: Materials and Techniques 16th–18th Century, edited by David Bourgarit, Jane Bassett, Francesca Bewer, Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Philippe Malgouyres, and Guilhem Scherf, 150–65. London: Archetype, 2013.

- Herda-Mousseaux 2018

- Herda-Mousseaux, Rose-Marie. “La dynastie des Darnault.” In La fabrique du luxe: Les marchands merciers parisiens au XVIIIe siècle. Exh. cat. Paris: Musée Cognacq-Jay, 2018.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Molinier 1902

- Molinier, Émile. Le mobilier royal français aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: Histoires et description. Vol 3. Paris: Goupil et Cie, 1902.

- Packer 1956

- Packer, Charles. Paris Furniture by the Master Ebénistes. Newport, U.K.: Ceramic Book Co., 1956.

- Pallot and Garnot 2006

- Pallot, Bill G. B., and Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot. Le mobilier français du musée Jacquemart-André. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2006.

- Parker, Appleton Standen, and Dauterman 1964

- Parker, James, Edith Appleton Standen, and Carl Christian Dauterman. Decorative Art from the Samuel H. Kress Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Tapestry Room from Croome Court, Furniture, Textiles, Sèvres Porcelains, and Other Objects. London: Phaidon Press, 1964.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Rieder 1980

- Rieder, William. “French Furniture of the Ancien Regime.” Apollo 216 (February 1980): 127–34.

- Roubo 1774

- Roubo, André Jacob. L’art du menuisier ébéniste. Paris: L. F. Delatour, 1774.

- Sargentson 1996

- Sargentson, Carolyn. Merchants and Luxury Markets: The Marchands Merciers of Eighteenth-Century Paris. London: Victoria and Albert Museum in association with the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996.

- Szabolcsi 1964

- Szabolcsi, Hedwig. French Furniture in Hungary. Budapest: Corvina Press, 1964.

- Watson 1966

- Watson, Francis John Bagott. The Wrightsman Collection. 5 vols. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1966.

- Webb 2000

- Webb, Marianne. Lacquer Technology and Conservation: A Comprehensive Guide to the Technology and Conservation of Both Asian and European Lacquer. Butterworth-Heinemann Series in Conservation and Museology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

- Wescher 1955

- Wescher, Paul. “French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century in the J. Paul Getty Museum.” Art Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1955): 115–35.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wilson 1975

- Wilson, Gillian. “The J. Paul Getty Museum: 6ème partie: Les meubles baroques.” Connaissance des Arts 279 (May 1975): 107–13.

- Wolvesperges 2000

- Wolvesperges, Thibaut. Le meuble français en laque au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2000.

| words