13. Secrétaire

- French (Paris), ca. 1755

- By Jacques Dubois (French, 1694–1763, master 1742)

- White oak and sycamore maple* veneered with panels of Chinese red lacquer on coniferous wood and painted with European lacquer; interior drawers of sycamore maple and Japanese arborvitae; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron hardware and locks; brèche d’Alep top; replacement silk velvet, and trim

- H: 3ft. 4 1/2 in., W: 3ft. 9 in., D: 1ft. 3 1/8 in. (102.8 × 114.3 × 38.4 cm)

- 65.DA.3

Description

The rectangular secrétaire has flat sides (figs. 13-1, 13-2) and a double bowed front. The forecorners are rounded, and the front lower profile is serpentine. The two front feet are rounded on the front, continuing the shape of the forecorners, and are also rounded on the surface facing inward. The two back feet are three sided: a flat side faces the back and the outward facing surface, and the side facing inward is rounded. The slab on the top is of brèche d’Alep cut to conforming shape and with a molded edge. The upper half of the front is occupied by a panel that forms the fall front of the secrétaire. Below are two doors, the one on the right fitted with a lock.

The upper corners of the piece are fitted with pierced mounts. Each is composed of a shaped central cabochon topped by shellwork and surrounded by C- and S-scrolls and a twining leafy branch set with a flower. At the bases of the rounded corners are small mounts composed of C- and S-scrolls, rock work and shellwork, and a rising plant with berries. At the top of each side, toward the back, is a mount composed of addorsed elongated C-scrolls supporting a cartilaginous shell form centered by an oval cabochon above and a pendant of leaves below. Beneath the doors a horizontal molding of alternating cabochons and flowers flanked by leaves runs along the sides and front of the secrétaire.

The forefeet are clad on their outer surfaces with curved pierced mounts formed by large C-scrolls containing a leafy branch, topped by small C-scrolls supporting a flame motif. Half of this mount is applied to each of the back legs.

The mount attached to the central apron consists of linked C- and S-scrolls edged with a shell-like motif carrying small leaves and supporting at its center an arrangement of three C-scrolls and leaves.

The fall front and the doors below are framed with gilt bronze. The continuous mount of the fall front is composed, in the main, of a burnished molding set with flame motif borders, overlaid with ivy and laurel leaves and branches amid burnished C-scrolls, with acanthus scrolls in the upper corners and at the center a cabochon pierced with a keyhole. The frame continues down the outer and lower edges of the doors. It carries similar elements but lacks the ivy leaves. The horizontal framing mount at the tops of the doors takes the form of a straight burnished double molding, intertwined with a long branch of laurel bearing leaves and fruits. The vertical border between the doors is composed of linked and burnished C- and S-foliate scrolls set with flame motif borders and a winding laurel branch. The keyhole escutcheons (the one on the left door is blind) are formed by C-scrolls enclosing pierced cabochons, surrounded by shell and flame motifs, topped by an acanthus leaf set with a smaller cabochon.

The fall front lowers on hinges to reveal a central open pigeonhole (fig. 13-3). On the left is a lockable drawer bearing a small rocaille escutcheon and on the right two additional drawers. The fronts of the drawers are serpentine. Above is an open compartment that extends across the width of the secrétaire. The interior is decorated with European red lacquer, and the drawer fronts are outlined in gold paint. The interior bodies of the drawers are lacquered black and the outer surfaces stained black. The lower drawer on the right is fitted with three compartments for writing implements. The surface of the fall front and the forward surface of the pigeonhole are covered with green velvet surrounded by a narrow gilded galon. The drawers are fitted with simple foliate pulls in gilt bronze.

The compartment behind the doors below is divided in half by a shelf, and the lower half further divided into two by a vertical partition (fig. 13-4). With the exception of the lower left compartment, the interior is painted red. The left-hand door is held in a closed position by a latch and eye. The right door carries the lock. The edges of both the doors are serpentine and follow the form of the attached gilt bronze framing mount.

The large panel of Asian red lacquer covering the front of the secrétaire with gold, black, and brown depicts eighteen Europeans hunting. All are dressed in jackets, breeches, and hats. Twelve of the men carry swords, eight are armed with muskets, and two hold tall lances. Three men are on horseback, and one, hatless, ties up the legs of a doe or small deer. All this activity takes place on an open plain dotted with shrubs and grasses. In the foreground a tree rises from rocks, and in the middle ground another tree grows immediately above it. To the left is a many-storied building with curved roofs and a cupola. At an open window stands an Asian person of indeterminate gender. The entire panel is framed with a narrow border of gold paint, applied to the carcass of the piece.

The left profile of the secrétaire (see fig. 13-1) is set with a lacquer panel that shows a rocky foreground on which small bushes and grasses grow. A tree rises at the center. In the middle and background is a collection of buildings, built on stilts, with curved roofs. A steeple rises in the background. The upper part of the panel is painted with a shattered pine tree and a bird. The panel is outlined with a narrow border of gold paint.

The right profile of the secrétaire (see fig. 13-2) is set with a lacquer panel showing in the foreground a house on stilts with a curved roof. Small trees and a large branch intrude into the scene, with a rocky outcrop above. In the middle ground is a similar stilted building in front of rocks planted with weeping willows. Three birds fly in the sky.

Marks

The secrétaire is stamped “IDUBOIS” and “JME,” for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes, on top of the front right post (fig. 13-5).

Figure 13-5

Figure 13-5Commentary

The secrétaire is stamped “IDUBOIS,” for Jacques Dubois.1 While the model for some of the mounts, wholly or in part, can be found on other pieces of furniture stamped by this maker, no other secrétaire of this form can be found in this master’s oeuvre, or indeed by any other ébéniste working in this period. Traditionally, all Parisian secrétaires are of greater height than width, but this piece is an exception. It has obviously been made to carry the rare and large panel of Asian lacquer, which has been cut into three pieces to form the fall front and the doors. The panel shows Europeans, probably members of the Dutch East India Company, hunting on foot and on horseback. The lacquer, which may have been made especially for export to the West, appears to have been assembled from two adjacent leaves of a folding screen (see “Technical Description” below). Despite the high value of the lacquer, the work on the rest of the secrétaire is not of the highest quality, displaying a certain crudeness sometimes encountered in Dubois’s work. The panel construction and the joinery of the carcass are unusual for work done in Paris at this time, and there is evidence that the secrétaire has undergone significant restoration (see “Technical Description” below).

As stated above, mounts of the same model appear on other pieces stamped by this master. The apron mount appears again on a commode by him that was sold from the collection of Léon M. Lowenstein in Paris in 19352 and on a corner cupboard, stamped “IDUBOIS,” that was sold at Christie’s, Monaco, in 1992.3 This corner cupboard was also set with corner mounts of the same model, placed at the top and bottom of the canted corners. The upper corner mounts are seen on an unstamped secrétaire, veneered with bois de bout marquetry and attributable to Dubois, that was sold from the collection of Madame Fenwick (Ethel M. Fenwick Cabell) at the Palais Galliéra in 1964.4

The framing mounts of the fall front and the outer edges and bases of the doors below are of the same model, with some additions, as those found framing the fall front of a lacquer veneered secrétaire en dos d’âne sold from the collection of Erich von Goldschmidt-Rothschild in Berlin in 1931.5 Mounts of the same model were set on a similar secrétaire en dos d’âne that was sold in Paris in 2002, and they were struck with the crowned C mark.6 Parts of the vertical mount set at the inner edge of one of the doors below the fall front are found in a mount of greater length and in a similar position on a secrétaire decorated with European lacquer, stamped “IDUBOIS,” that passed through the Paris market in 1990.7 This mount also bore crowned C stamps. On the basis of these datable mounts it is possible to date the Museum’s secrétaire to about 1755.

Provenance

–1951: Rosenberg & Stiebel, Inc. (New York, NY), sold to J. Paul Getty; 1951–65: J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, donated to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1965.

Exhibition History

Imagining the Orient, J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center (Los Angeles), October 5, 2004–April 3, 2005.

Bibliography

, 118, 122, 130, fig. 15; , 120–21, ill.; , 150–51, ill.; , 273; , 55, ill.; , 37, no. 43; , 42, 45, fig. 28; , 25, no. 43; , 401, figs. 23–32; , S131.

- G.W.

Technical Description

This secrétaire has clearly been heavily restored, making a complete understanding of its history difficult to ascertain. In terms of its joinery, the construction of this secrétaire is unusual for Parisian work of the mid-eighteenth century.8 The case is based on only two real posts—substantial timbers that run from the top of the case to the floor—rather than the usual four. The two posts are in the two front corners and are made of sycamore maple. The sides of the case are each made of three 2.5-cm-thick boards of white oak that are joined to each other and to the front posts with loose splines (fig. 13-6). This type of joint is atypical of Parisian work. At the rear corners, rather than true posts, there are pseudo-posts created by gluing an extra piece of oak, about 2.5 cm x 4 cm in section, to the side panel, doubling its thickness at the back edge. The overall quality of the oak used throughout the case is relatively low, with curving grain and numerous knots.

Figure 13-6

Figure 13-6At the top (fig. 13-7) and bottom of the case front, long, shaped rails of sycamore maple connect to the front posts with mortise-and-tenon joints. In addition, sycamore maple blocks have been applied to the lower portion of the case sides and front posts in order to provide the added dimension necessary below the level of the horizontal cabochon and flower molding. On the sides, the concave oak substrate has been cut back to provide a flat bedding for these sycamore maple blocks. The widespread use of sycamore maple for all surfaces that are finished in European lacquer is a strong indication that the case was constructed for the express purpose of being lacquered (see the discussion of substrates for European lacquer in cat. no. 5).

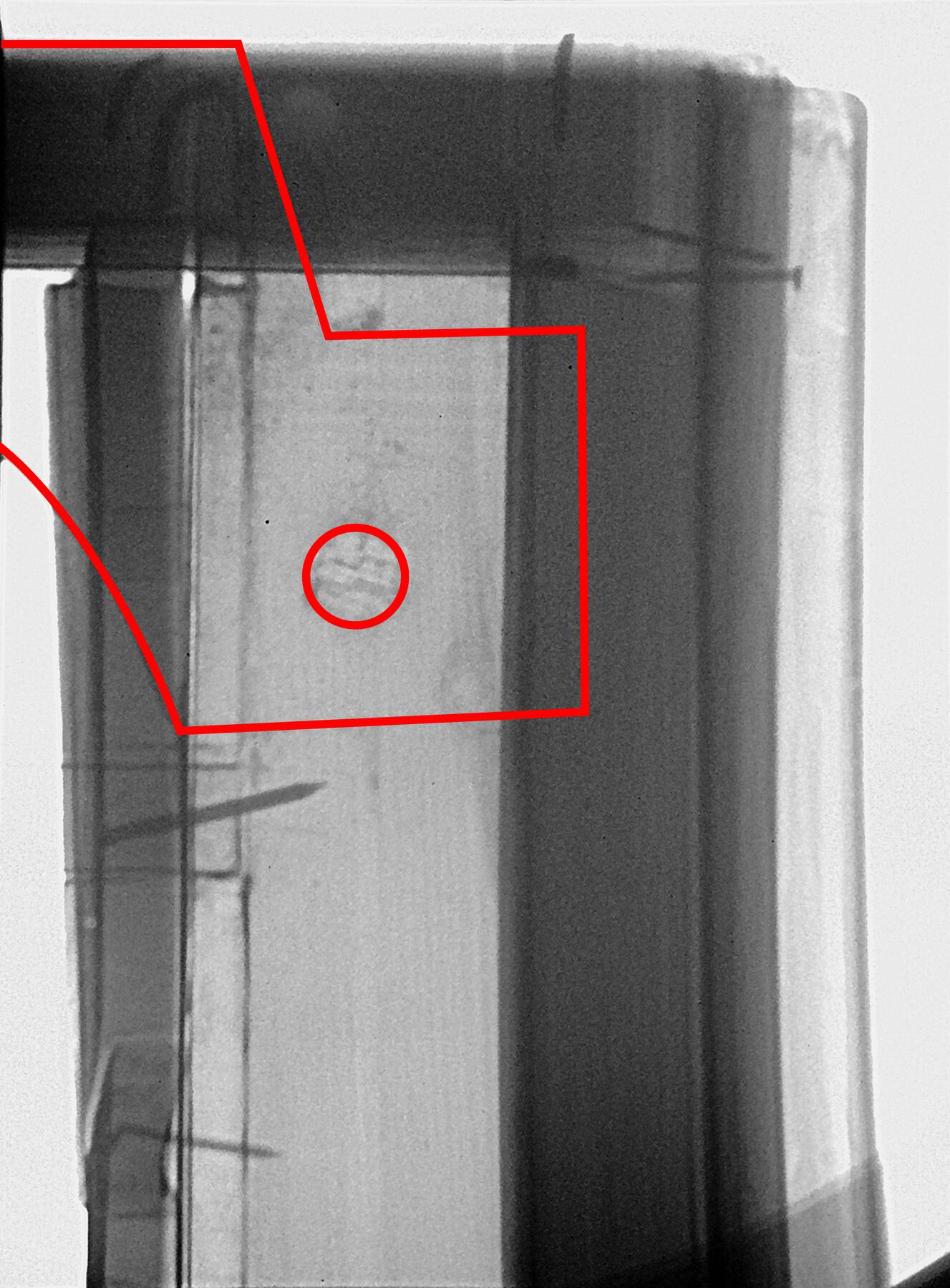

The case back is assembled as a bipartite frame-and-panel construction with rails at the top and bottom that are mortise and tenoned (with oak pegs) into the tops and bottoms of the pseudo-posts. The tenons of the upper rails, both front and back, have been cut in an unusual manner, with an angled shoulder, visible in X-radiographs (fig. 13-8). The one vertical stile in the frame-and-panel construction is attached to the upper and lower rails with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints, executed in the traditional manner. This stile has fine ogee moldings cut along its length on the interior edges. The grooves in the pseudo-posts that hold the back panels have been cut continuously from the top of the case to the floor and are clearly visible on the inner faces of the back legs.

Figure 13-8

Figure 13-8The unusually large back panels are each made of seven pieces of wood, with the grain running from side to side (fig. 13-9); the horizontal configuration of these boards is unusual in such a tall and narrow panel. Normally in an elongated panel the grain direction corresponds to the longer dimension, thus minimizing the effects of cross-grain shrinkage (see, e.g., the back panels in cat. nos. 4 and 12). Significant shrinkage has in fact occurred in the panels, and as a result strips of oak over 1.5 cm wide have been inserted in the upper sections of each panel to compensate. These repair strips are only as long as the space between the posts and the center stile and thus were almost certainly added without disassembling the case.

Figure 13-9

Figure 13-9The back panels are rather crudely beveled on the back face and still retain some pit saw marks. The individual boards are assembled with tongue-and-groove joints. Many boards have a tongue on one edge and a groove on the other; unusually, however, some boards have either tongues or grooves on both edges, and there is no apparent pattern or logic to the arrangement. Several of the boards in each panel are somewhat tapered. On the whole, this method of panel construction appears to be more common in Dutch furniture than in French.

The case top is made of three fairly narrow boards of oak, butt joined, with their grain running from side to side; these are attached to the case sides with open-faced dovetails. The dovetails are rather imprecisely cut and are asymmetrically arranged; on the proper right side there are six dovetails, while on the proper left side there are only five. At the front and the rear, the case top is glued and nailed into a dado cut into the adjacent rails (fig. 13-10). The nails that currently hold it in place appear to be of wire, and there is no evidence of prior nails.

Figure 13-10

Figure 13-10The case bottom is made of three boards of oak that are attached to the side panels with four mortise-and-tenon joints. The tenons are the full thickness of the bottom panel. The bottom is attached to the back rail with glue and also by means of a peg that runs through the mortise and tenon between the medial stile and the bottom rail of the back and into the case bottom.

The fall front of the secrétaire is made of several horizontal boards with battens or “breadboard ends” positioned vertically at either end. X-radiography reveals that the horizontal boards are butt joined, while the battens are attached with tongue-and-groove joints. The lower doors are similarly constructed using simple butt-joined boards with breadboard ends; however, in the case of the doors, the battens are horizontal (at top and bottom) and the panel boards are aligned vertically. The green velvet writing surface on the interior of the fall front is not original. Beneath it lies a deteriorated leather writing surface surrounded by a border strip of sycamore maple veneer approximately 4 cm wide coated with European red lacquer.

Behind the fall front, the drawer fronts, shelves, and vertical dividers retaining the drawers are made of sycamore maple. The vertical dividers are attached at top and bottom with sliding half dovetails. There has evidently been some modification to the arrangement of the upper case interior as the top of the horizontal divider is notched at the center as if to receive an additional vertical divider, now missing. There is no corresponding notch on the bottom of the case top, suggesting that there may have been an intermediate shelf at some point in the past. The several thin panels with curved edges on the sides of the inner case are held in place with modern wire nails.

The bottoms and sides of the drawers in the upper case are made of a wood identified in 1994 by Bruce Hoadley as Japanese arborvitae. This is lacquered on the interior surfaces with a simple Asian black lacquer (fig. 13-11). The outer surfaces of these panels are roughly planed and stained black, suggesting that they were salvaged and reused from unornamented parts of a piece of Asian lacquered furniture.

In the lower part of the case, the horizontal shelf is supported above and below by rails that are simply glued and nailed to the inside of the case sides at both ends. The nails that currently hold it in place appear to be wire nails, and there is no evidence of prior nails. The vertical divider is tenoned with four tenons on the bottom and four tenons on the top to hold it in position. The proper right compartment at the lower level is the only one without European red lacquer on the interior. Evidence of wear from a lock bolt on the inside edge of the oak post on the proper right side of the compartment suggests that it once contained a strong box or similar fitting, now missing.

While the stylistic attributes of the lacquer panels leave some ambiguity as to their origin, the lacquer stratigraphy and composition closely resemble known examples of Chinese export lacquer, which can also be seen on the Van Risenburgh red lacquer commode (see cat. no. 6). In X-radiographs it is possible to see the joints between the original Asian wood boards on which the lacquer was applied (fig. 13-12). The grain of the boards runs vertically, and the boards vary from about 10 to 15 cm in width. X-radiography also shows that the lacquer on the front likely comes from two panels of a folding screen. Just to the left of center, the vertical seam between the two panels is clearly visible as an abrupt change in density. Discontinuous cracks in the lacquer along the edges of the panels clearly indicate that they are separate panels. The panel on the right is approximately 54 cm in width, which is within the normal range for panels of eighteenth-century Chinese folding screens.

Figure 13-12

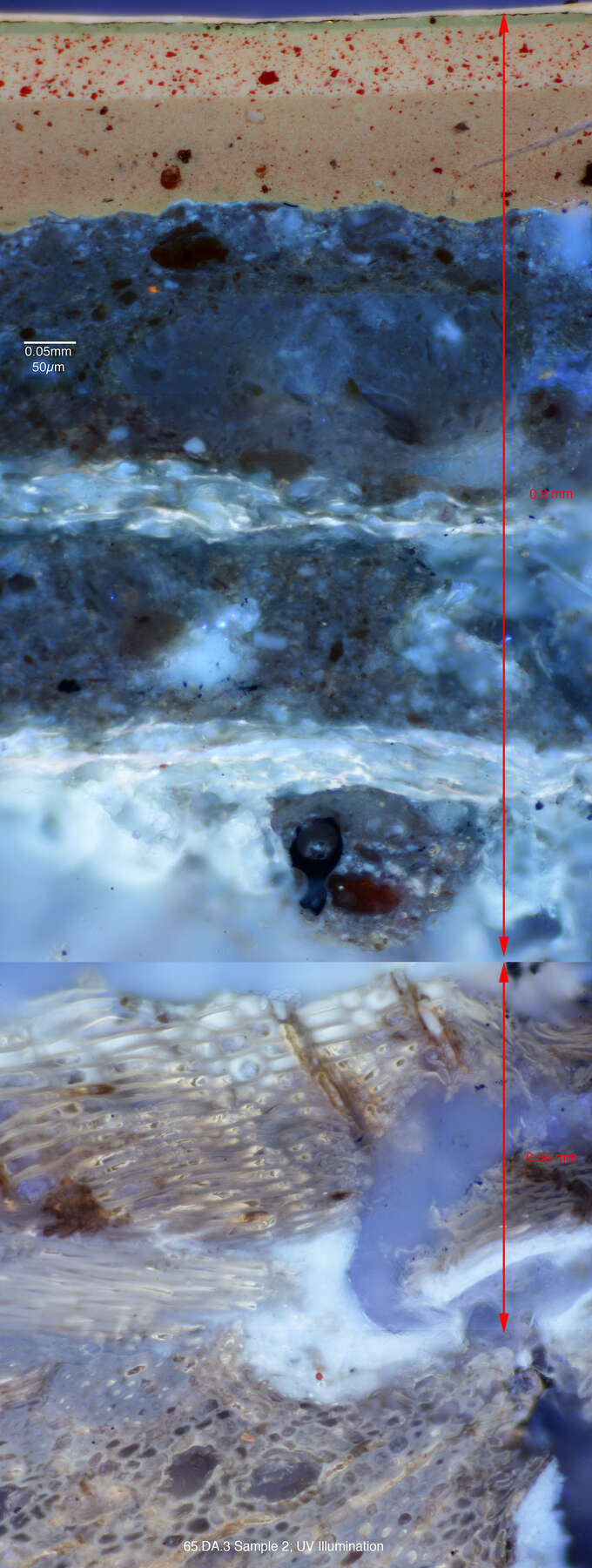

Figure 13-12Cross-section analysis shows that the substrate wood of the lacquer panels is from the cypress family (Cupressaceae) and was prepared with two to three layers of clay-based ground material bound in blood, with each layer separated by a paper interlayer. Pig’s blood is referenced in nineteenth-century accounts as an ingredient in Chinese lacquer foundation layers and has been commonly found in the analyses of many Chinese lacquer objects, frequently used alongside drying oil (figs. 13-13, 13-14).9 The ground layer may also contain a small amount of cedar oil, although this cannot be definitively confirmed.10 On top of the ground, a layer of red lacquer made with iron earth pigment was applied; this was followed by a layer of brilliant red lacquer prepared with vermilion pigment. Analysis by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (py/GC-MS) shows that the lacquer used to prepare the red layers is not the traditional Chinese qi lacquer (extracted from trees of the species Toxicodendron vernicifluum). Instead, this lacquer seems to be made from so-called Vietnamese lacquer, based on the polymer of laccol and derived from T. succedaneum. This does not mean that the lacquer necessarily originated in Vietnam, as the trees are widespread in East Asia and are commonly tapped for lacquer in parts of southern China and Taiwan as well.11 Vietnamese lacquer has been reported in several pieces known to have originated in Guangzhou, also known as Canton, which was a major center of lacquer production and trade in southern China.12 This laccol lacquer was commonly mixed with a drying oil, which was also detected with py/GC-MS in the lacquer layers of the secrétaire. The samples also contain a small fraction of carbohydrates, which are most likely related to the naturally occurring carbohydrates in the laccol sap.13

Figure 13-13

Figure 13-13 Figure 13-14

Figure 13-14The decoration of the lacquer panels is executed in a variety of metal powders, including gold (primarily for the figures’ clothes), brass (used widely in buildings and horses), and tin (found in the figures’ socks, cravats, and dark pants).14 The metal flake decoration is almost entirely flat, the only exception being the figures’ faces, which are in very low relief. The panels have an unusual pattern of long diagonal cracks crossing over a more typical gridlike pattern of cracks (fig. 13-15). This may be related to the fact that the lacquer is unusually thick; together, the three-layered ground with the two red foundation layers measures nearly 1 mm. Cross sections suggest that panels were thinned to less than 1.3 mm before being applied to the carcass of the secrétaire, leaving only a very small amount of wood to support the brittle lacquer layers. It is possible, then, that some of the diagonal cracking is the result of flexing that occurred when the panels were first thinned and manipulated in the eighteenth century. This is supported by the observation that some of the diagonal cracks on the front of the secrétaire appear to continue across the divisions between the fall front and the lower doors, suggesting that they occurred before the panel was divided.

Figure 13-15

Figure 13-15The decorative work on the lacquer panels has undergone significant restoration in the past, much of it executed very skillfully. Several of the figures have been entirely restored, others partially (fig. 13-16). Examination under magnification reveals that much of the foliage, particularly the grasses in gold, have been restored using a dark red underlayer, or size, which is distinguishable from the brilliant red underlayer of the original lacquer work. The largest area of restoration is on the proper right door and covers the centermost 10 cm, from top to bottom. This restoration entirely replaces the original lacquer; the reason for the loss of so much original material is not known.

Figure 13-16

Figure 13-16X-radiography of the fall front, doors, and side panels reveals the presence of numerous wire nails embedded in the carcass beneath the lacquer, most of which (mysteriously) are not perpendicular to the surface. The judicious use of a magnet confirms that many of these nails lie close to the exterior surface but beneath intact and “unrestored” passages of lacquer. Fine drawn-iron wire nails were available in the mid-eighteenth century, and the process of their manufacture is well documented;15 however, industrially produced versions only became commonplace in the late 1880s. Without direct access to the nails, it is difficult to date the production of these specific nails. One possible explanation for the presence of these nails is that sometime between the late nineteenth century and 1951, when the secrétaire was acquired by J. Paul Getty, the Asian lacquer, being in very poor condition, was removed entirely from the piece, then consolidated and reattached as part of a major restoration. Another possibility that cannot be ruled out entirely, however, is that the lacquer panels are not original to the piece and were added later to replace severely damaged original Asian or European lacquer.

The European lacquer on the exterior of the secrétaire (surrounding the Asian panels) is not original. Scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) of cross sections indicates that any original European lacquer had been completely stripped off. The existing layers are colored with a complex mixture of pigments that include a red lake (cast on a substrate that includes barium sulfate), chrome yellow, and zinc white. The history of manufacture of these pigments suggests strongly that the lacquer was restored after about 1840.16 Furthermore, very close similarities in elemental composition between the restored European lacquer on the case exterior and large areas of restoration in the Asian lacquer (as determined by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry [XRF]) suggest that both were done at the same time, probably in the first half of the twentieth century. Based on py/GC-MS analysis, restoration coatings applied on top of the Asian lacquer appear to be primarily shellac. The existing exterior European lacquer has been artificially patinated with evenly distributed dents and umber-colored pigment applied around the mounts. This pattern of “distressing” is distinct from any damage or soiling found on the Asian lacquer panels.

As mentioned in “Commentary” above, the gilded bronze mounts are almost all models that appear on other works stamped by Dubois. Quantitative XRF spectroscopy of fourteen representative mounts from the secrétaire revealed that the alloy of the mounts is typical in all respects of French eighteenth-century casting brass. The composition of the metal, particularly the presence of significant impurities, including antimony and silver combined with relatively low levels of zinc (17–23%) and relatively high levels of tin (0.8–1.5%), makes it extremely unlikely that the mounts are late nineteenth- or twentieth-century castings. The gilding is generally in good condition. XRF analysis detected traces of mercury in the gilding, suggesting that they have been amalgam gilt; however, the presence of small amounts of gold on the back sides of the mounts, even where no gilding is present, may be an indication that the mounts have been regilded by electroplating.

The quality of the chasing and finishing of the mounts is only fair, and the mounts’ arrangement is somewhat awkward. For example, similar passages along the outer edges of the primary framing mounts that surround the fall front and doors have been filed and chased in dissimilar ways. The transitions between mounts are rather crude. This is particularly noticeable where the horizontal mount along the bottom edge of the fall front meets the framing mounts at either end and also where the vertical mount between the doors joins with the mounts above and below. Jacques Dubois managed a very large workshop and is thought to have kept many mounts in stock and ready for use as necessary. It may be that this secrétaire is an example of a model of furniture for which a new suite of mounts was not designed, but rather a selection of preexisting mounts was selected and adapted to fit a new form.

Both of the exterior locks, as well as the hook and loop that secure the proper right door, have been replaced. This is evident from the evidence of old, superfluous screw holes and changes to the shape of the lock mortises.

The stamp on the top of the proper left front leg (“IDUBOIS”) (see fig. 13-5) is very similar in size and detail to that found on the monumental corner cabinet stamped Dubois (see cat. no. 11 and fig. 11-1). However, both of these stamps are rather different from the Dubois stamp found on the pair of black lacquered corner cupboards (see cat. no. 12 and fig. 12-2). Little is known for certain about how many different stamps might have been used by individual workshops (particularly large shops such as Dubois’s), though the guild regulations of the time seem to suggest that there should have been only one. In the case of Dubois, the matter is complicated by the fact that his son, René (master 1755), is also said to have used his father’s stamp.

The secrétaire’s marble tabletop is approximately 2.3 cm thick and is made of brèche d’Alep, a heterogeneous marble consisting of multicolored, somewhat rounded cobbles in a beige to orange sand and gravel matrix. The predominant color of the cobbles is from tan to cream, although red and even black cobbles are found as well. Many similar limestone breccias of this type occur in varying colors throughout the Mediterranean. The original Alep Breccia is from Syria. This stone, however, is thought to have been quarried in Le Tholonet, Bouches-du-Rhône, France. Although the quarry is inactive now, it had been in use since ancient times. Near the proper right end, the slab has been broken into five major fragments and repaired with four iron cramps.

- A.H.,

- J.C.,

- M.S.,

- and R.S.

Notes

For more information on Jacques Dubois, see , 168–75; , 42–59; , 283–91. ↩︎

Galerie Jean Charpentier, Objets d’art et de bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle, December 17, 1935 (Paris: Galerie Jean Charpentier, 1935), lot 136. ↩︎

Christie’s, Mobilier et objets d’art, February 28, 1992 (Monaco: Christie’s, 1992), lot 67. ↩︎

Palais Galliéra, Tableaux anciens, dessins, aquarelles, gouaches, pastels, bel ameublement du XVIIIe, tapisseries, meubles et objets d’art, December 8, 1964 (Paris: Palais Galliéra, 1964), lot 154. ↩︎

Hermann Ball & Paul Graupe, Sammlung Erich von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, March 16, 1931 (Berlin: Hermann Ball & Paul Graupe, 1931), lot 123. ↩︎

Christie’s, Important mobilier, objets d’art, orfèvrerie, céramiques européennes, arts d’Asie, June 24, 2002 (Paris: Christie’s, 2002), lot 206. ↩︎

, 286, fig. 153; Drouot Richelieu, Dessins et tableaux anciens, objets d’art et bel ameublement des XVIe, XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, tapisseries, tapis, March 19, 1990 (Paris: Drouot Richelieu, 1990), lot 67. ↩︎

For their valuable insights into the construction of this secrétaire, the authors would like to acknowledge Yannick Chastang, Paul van Duin, and Antoine Wilmering. ↩︎

, 200; , S185. ↩︎

For additional information about the capabilities and limitations of lacquer analysis, see “The Analysis of East Asian and European Lacquer Surfaces on Rococo Furniture,” in this volume. ↩︎

, 502–3. ↩︎

; , 7–8. ↩︎

. ↩︎

The metals present were determined using qualitative X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). Spectra are on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 53–54, pl. II. ↩︎

, 170–72; , 188–89. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Boiron 1990

- Boiron, Stéphane. “Jacques Dubois, maître de style Louis XV.” L’Estampille/L’Objet d’Art 237 (June 1990): 42–59.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Getty 1963

- Getty, J. Paul. Chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection J. Paul Getty. Monaco: Jaspard, Polus et Cie, 1963.

- Getty 1965

- Getty, J. Paul. The Joys of Collecting. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1965.

- Gray 1875

- Gray, John Henry. Walks in the City of Canton. Victoria: De Souza & Co., 1875.

- Harwood, May, and Sherman 2002

- Harwood, Buie, Bridget May, and Curt Sherman. Architecture and Interior Design through the 18th Century: An Integrated History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002.

- Heginbotham et al. 2016

- Heginbotham, Arlen, Julie Chang, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling. “Some Observations on the Composition of Chinese Lacquer.” Studies in Conservation 61, suppl. 3 (2016): S28–S37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2016.1230979.

- Kühn and Curran 1986

- Kühn, Hermann, and Mary Curran. “Chrome Yellow and Other Chromate Pigments.” In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, edited by Robert L. Feller, 187–217. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Kühn 1986

- Kühn, Hermann. “Zinc White.” In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, edited by Robert L. Feller, 169–86. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Kumanotani 1995

- Kumanotani, J. “Urushi (Oriental Lacquer): A Natural Aesthetic Durable and Future-Promising Coating.” Progress in Organic Coatings 26 (1995): 163–95.

- Petisca et al. 2011

- Petisca, Maria João, José Frade, Margarida Cavaco, Isabel Ribeiro, Antónió José Candeias, José Graça, and José Carlos Rodrigues. “Chinese Export Lacquerware: Characterization of a Group of Canton Lacquer Pieces from the 18th and 19th Centuries.” In ICOM-CC 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon, 19–23 September 2011: Preprints, edited by Janet Bridgeland, 10. Lisbon, Portugal: Critério-Produção Grafica, 2011.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Réaumur 1761

- Réaumur, René Antoine Ferchault. Art de l’épinglier, par M. de Réaumur, avec des additions de M. Duhamel Du Monceau, et des remarques extraites des mémoires de M. Perronet . . . Paris: Saillant et Nyon, 1761.

- Schilling et al. 2014

- Schilling, Michael, et al. “Chinese Lacquer: Much More Than Chinese Lacquer.” Studies in Conservation 59, suppl. 1 (2014): 131–33.

- Wan et al. 2007

- Wan, Yun-Yang, Rong Lu, Yu-Min Du, Takayuki Honda, and Tetsuo Miyakoshi. “Does Donglan Lacquer Tree Belong to Rhus vernicifera Species?” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 41 (2007): 497–503.

- Webb, Schilling, and Chang 2014

- Webb, Marianne, Michael R. Schilling, and Julie Chang. “The Reproduction of Samples of Chinese Export Lacquer for Research.” Studies in Conservation 59, suppl. 1 (2014): S184–S187.

- Wescher 1955

- Wescher, Paul. “French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century in the J. Paul Getty Museum.” Art Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1955): 115–35.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wolvesperges 2000

- Wolvesperges, Thibaut. Le meuble français en laque au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2000.