12. Pair of corner cupboards

- French (Paris), ca. 1755

- By Jacques Dubois (French, 1694–1763, master 1742)

- White oak veneered with pear* and bloodwood, set with leather panels of Chinese black lacquer, and painted with European lacquer; gilt bronze mounts; brass and iron hardware and locks; brèche d’Alep top

- H: 3 ft. 2 1/4 in., W: 2 ft. 7 1/2 in., D: 1 ft. 11 1/4 in. (97.2 × 80 × 58.7 cm)

- 78.DA.119.1–.2

Description

Each corner cupboard has a bowed front and is fitted with a single lockable door. It is supported on four short legs, three of which are of cabriole form. The two outer legs are five-sided in section, while that in the center front has an almost flat outer surface and a curved back. The fourth leg at the back of the piece is L-shaped in section, fitted with a block of smaller dimensions. The stone tops are of brèche d’Alep, cut to conforming shape and with a molded front edge.

The corners are set with pierced gilt bronze mounts. Each consists of a central cabochon set in a C-scroll, edged by a leafy border. This is enclosed on either side by hipped scrolls of C and S form, fringed with a shell-like form, terminating in scrolling leaves below and rising above to an S-shaped platform, resting on and supporting leafy motifs. A leafy twig bearing three berries rises from the lower part of the mount, twining and appearing to either side of the main arrangement as it rises. Each corner mount is the reverse of the one opposite it.

A straight mount of overlapping leaves and berries descends from this mount to the top of the leg, where it joins a cluster of acanthus leaves. These leaves overhang a concave molding that extends horizontally across the front of the corner cupboard, immediately below the single door. A short plain molding extends from the acanthus leaves down the outer edge of each outer leg to the scrolled and pierced foot mount. Each foot is composed of S-scrolls enclosing an arrangement of leaves from which rises a short stem carrying leaves and berries, set against a large divided leaf. A mount of the same model is set on the central foot, and a twisted rope molding rises from either side to outline the lower profile of the corner cupboard. Above the central leg is a small mount in the form of a shell flanked by foliated C-scrolls.

The door is set with a large continuous framing mount composed of C- and hipped S-scrolls set with leaves. On either side rise twining leafy branches carrying berries. Shorter flowering branches emerge above and descend to either side. The center of the upper part of the frame is composed of four addorsed C-scrolls asymmetrically arranged, set with leaves, leafy twigs, and berries. In the middle of the lower section of the framing mount is a larger rising asymmetrical arrangement of C-scrolls set above a large pierced shell, which is supported by further C-scrolls. Short branches bearing flowers emerge from the left and above.

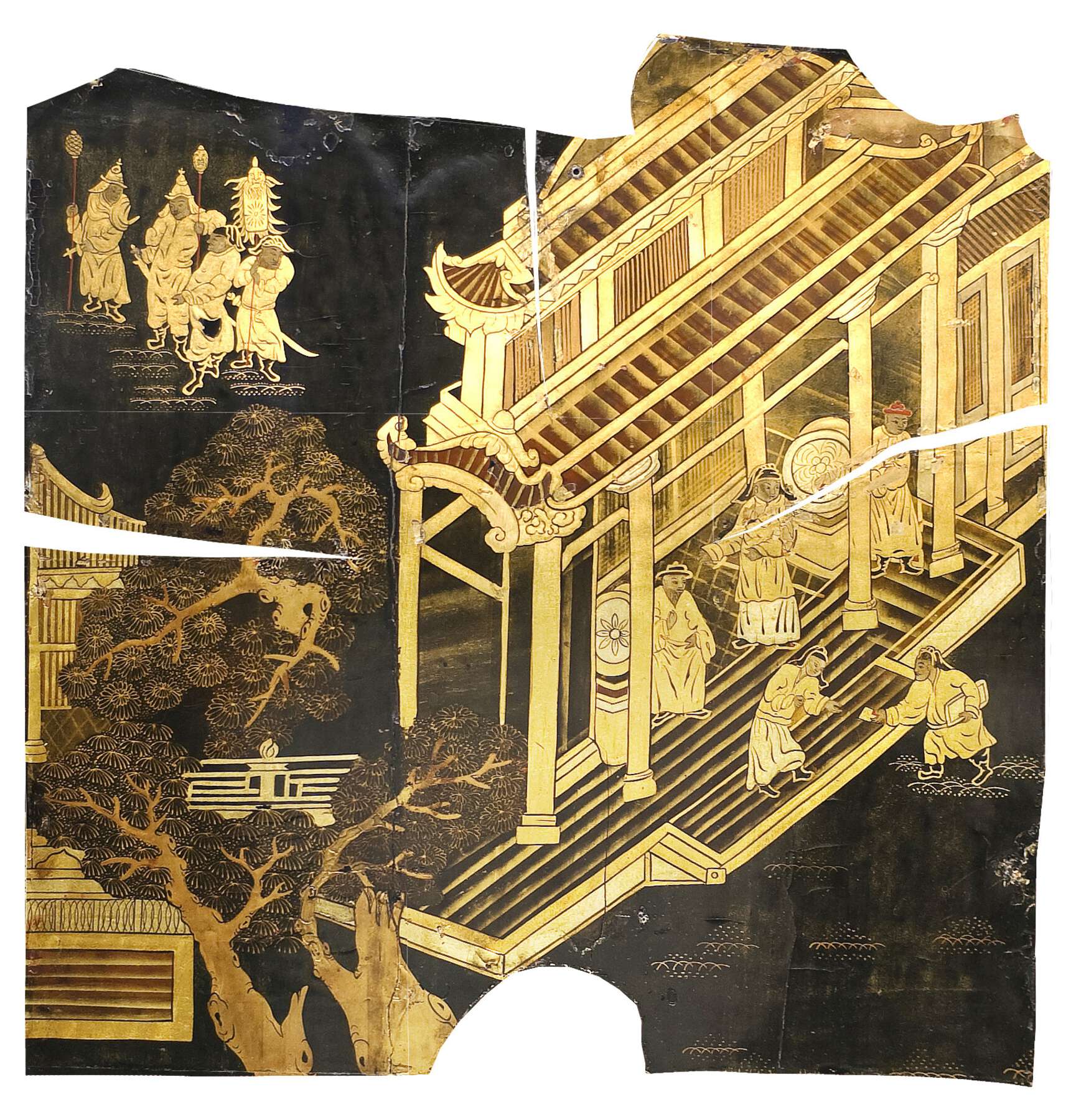

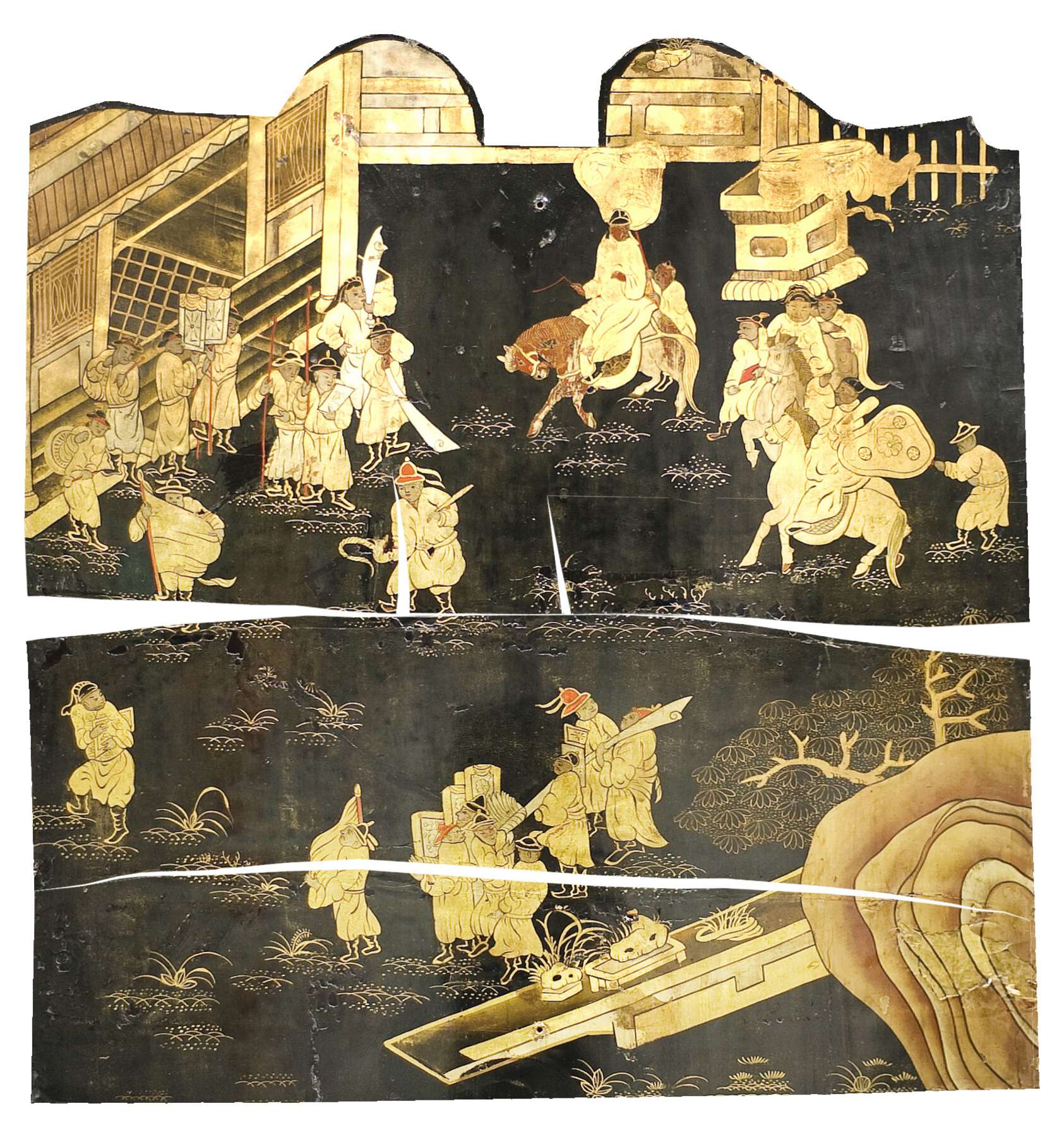

The doors are set with leather panels of Chinese black lacquer featuring three tones of gold and touches of vermilion and red ocher. The scene on corner cupboard .1 shows an open fenced area in front of a house with a pillared porch. Above right are three horses depicted in two tones of gold on which is set a lord attended by two members of his court and servants carrying fans. In front of the house are ten more servants, each wearing a short-brimmed hat, engaged in various actions. Two carry swords, two carry red staves, two carry standards, and two beat drums. Another carries a large flag that the wind has wrapped around his body. The tenth figure is damaged, and it is not possible to define his task. In the center are seven more servants. One carries a sword, another a flag, and two carry standards. The activities of the remaining figures are not comprehensible, probably due to incorrect overpainting. The ground is painted with tufts of grass, and a tree emerges from behind a rock on the lower right.

The lacquer on cupboard .2 depicts a large open temple held up by columns. Inside are three figures, one bearded and seated, and two large drums. A fourth man stands on the staircase and receives a letter from a messenger. To the left of the temple a large tree stands in front of various structures. Above is a group of four warriors. All carry swords. One bears a standard, and two others carry scepters on the ends of long red poles.

The remaining surfaces on the facades of the corner cupboards are decorated with European black lacquer, and each door is outlined with a narrow border of gold paint. Each lock plate is partly concealed by the framing mount. Set between broad scrolls and a leafy emergence, they take the form of simple stippled plates centered by keyholes. The interior surface of each door is veneered with an outer frame of quartersawn bloodwood surrounding four panels of the same veneer. The cupboards are fitted with a single shelf, and the entire interior surface is covered in European vermilion red lacquer (fig. 12-1).

Figure 12-1

Figure 12-1Marks

Each corner cupboard is stamped on top of the front right leg stile “IDUBOIS” once and “JME,” for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes twice (fig. 12-2).

Figure 12-2

Figure 12-2Commentary

The corner cupboards are stamped “IDUBOIS,” for Jacques Dubois.1 A pair of corner cupboards in the Palazzo del Quirinale in Rome carries a framing mount on their single doors of the same floral and extremely asymmetrical model (fig. 12-3).2 They are stamped by Dubois, and apart from having similar profiles and measurements (105 x 85 x 54 cm) they carry mounts elsewhere of differing models and are veneered with bois de bout marquetry. No other corner cupboards of this design by Jacques Dubois are known.

Figure 12-3

Figure 12-3Corner mounts of the same model can be seen on a small commode veneered with Chinese lacquer and stamped by Dubois in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.3 A commode stamped by this master veneered with amaranth banding and bearing corner and feet mounts of the same model was sold in Paris in 1954.4 A bureau plat set with corner mounts of this model and veneered with panels of lacquer, of similar form to that in the musée du Louvre made for the duc de Choiseul,5 was sold from the Patiño Collection in New York in 1986.6 In an inventory taken of Dubois’s large workshop at his death in 1763 the following is listed: “2 grandes encoignures aussi de vernis de la Chine à cartels, prisées 1 000 l.”7

In J. Paul Getty’s diary for 1950 he notes that in September he visited Lionel Levi of Cameron’s in London, where he saw “a fine pair of Louis XV lacquer encoignures L3,500. Agreed to the price.”8 Evidently the final transaction with Getty was held a month later by Levi’s associate Frank Partridge, and the price given in the files of the Museum is $11,931.93. The cupboards were sent to Malibu, but Getty asked for their return in 1960, and they remained in Sutton Place until just before his death. They were returned to the Museum in 1975. The years of exposure to the uncontrolled climate in both Sutton Place and the Ranch House in Malibu have taken their toll on the Chinese lacquer. They have been restored and repainted so many times that little of their original surface remains visible (see “Technical Description” below). For this reason the corner cupboards have never been on display in the Museum.

A note in the Museum’s files states that the corner cupboards were once in the collection of Nathaniel von Rothschild of Vienna.9 This provenance appears to be incorrect. Nathaniel von Rothschild’s collection was in part restituted in 1947 to Clarice von Rothschild, who sent it to Rosenberg & Stiebel in New York. Gerald Stiebel cannot find a mention of the corner cupboards in the company’s archives and thinks it is unlikely that his forebears would have passed them to a London dealer.10 The original invoice, provided by Frank Partridge, makes no mention of a Rothschild provenance. In Collector’s Choice Getty writes, “I have a pair of black lacquer Louis XV encoignures by Dubois. I’d been in the market for such a pair for about fifteen years before I saw these at Partridge’s in London. Their beauty and elegance so impressed me that I bought them—regardless of their high price—without hesitation. Frank Partridge was under the impression that these also came from one of the Rothschild collections. But their previous ownership was never fully confirmed.”11

It is likely that the corner cupboards were in fact sold by Francis David Charteris, the twelfth Earl of Wemyss and eighth Earl of March (1912–2008), at Christie’s on March 7, 1946: “99 A PAIR OF LOUIS XV ENCOIGNURES, each enclosed by one door, lacquered with Chinese figures and buildings in gold heightened with red on black ground, mounted with ormolu borders to the panels and corner mounts chased with sprays of flowers entwined with scrollwork, surmounted by giallo marble slabs—32 in. wide stamped I. Dubois, ME.”12 Unfortunately, the sale catalogue is not illustrated.

They were acquired by Raphael Rosenberg for 890 guineas.13 He was in partnership with his brother Saemy, having left Germany before World War II. The London company was known as S&R Rosenberg Ltd. There is a likelihood that they bought the corner cupboards together with Levi of Cameron’s and Frank Partridge, but this has yet to be confirmed.14

Provenance

–1946: Francis David Charteris, twelfth Earl of Wemyss and eighth Earl of March, Scottish, 1912–2008 (Gosford House, Longniddry, East Lothian, Scotland) [sold, Old French and English Furniture and Porcelain [ . . . ], Christie’s, London, March 7, 1946, lot 99, to Raphael Rosenberg]; 1946– : Raphael Rosenberg, German, 1894–1968;15 –1950: Cameron and Frank Partridge & Sons, Ltd. (London, England), sold to J. Paul Getty, 1950; 1950–76: J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976 (Sutton Place, Surrey, England), upon his death, held in trust by the estate; 1976–78: Estate of J. Paul Getty, American, 1892–1976, distributed to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1978.

Exhibition History

Connecting Seas: A Visual History of Discoveries and Encounters, Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles), December 7, 2013–April 13, 2014.

Bibliography

, 151, 167; , 118, 122, 130, fig. 14; , 81, ill.; , 120, ill.; , 150, ill.; , 145, no. 234; , 273; , 56, ill.; , 33–34, no. 38; , 22, no. 38; , S221–S222, fig. 1; , S131; , 91–96, figs. 1a–1b, 5c–5d, 6, 8.

- G.W.

Technical Description

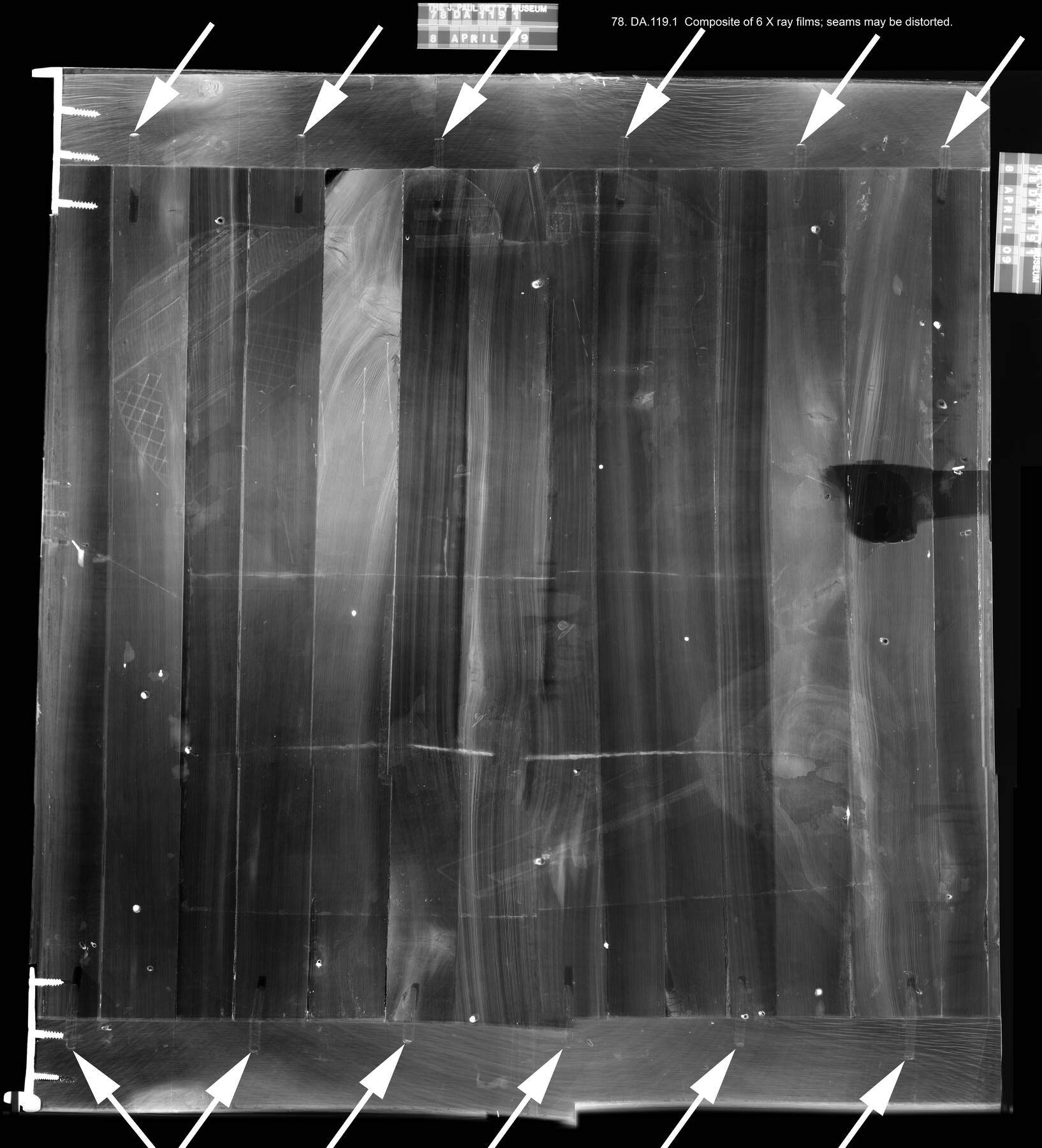

At first glance, these corner cabinets appear to be assembled using standard frame-and-panel construction (fig. 12-4). A look at the underside quickly reveals, however, that things are not as they initially appear (fig. 12-5). Dovetails join the case back panels to the case bottom, and what first appear to be lower structural rails (securing the front and rear legs) are little more than thin battens of oak that were nailed across the case back without structural function. X-radiographs confirm that the same is true at the top of the case; ersatz rails are nailed along the top rear edges, seemingly to conceal the underlying dovetail joints and give the impression of frame-and-panel construction (fig. 12-6). The two back panels of each cabinet are joined to each other at the back corner with a simple dado, secured with glue and nails. The panels are each assembled from three boards of rather poor quality oak. In each case, the board closest to the back corner is longer than the others and runs down to the floor. These boards have been sawn to shape and form the basis of the rear foot. Once again, the functional joint between the rear panels is concealed with oak battens of negligible structural utility, giving the false impression of a solid post at the rear corner.

The back panels are attached to the two front posts with tongue-and-groove joints; as is commonly the case, the grooves can be seen extending below the case bottom on the rear face of the front legs. Even the front corner posts are not entirely what they appear. While there are indeed solid posts at the corners, they have been augmented on their inside and outside faces, as well as on their tops, with oak battens analogous to those used on the case back. The reasons for doing this are not readily apparent; the resulting composite post is not unusually large, and a single block of wood could easily have been used. It is possible that the widening of the posts represents a modification to accommodate corner mounts that are larger than those anticipated in the original carcass design. Another unusual feature of the front posts may lend credence to this supposition. When the corner mounts are removed, one sees that bulbous blocks of wood, approximately 10 cm high by 5 cm wide, have been inserted into the posts behind the mount’s central cabochon (fig. 12-7). The surfaces of these blocks are visible through the piercing of the corner mounts; it appears to have been necessary to add these blocks because the original contour of the post was too shallow to adequately fill the space behind the current mounts. This, again, supports the idea that the original carcass design was conceived with different, less protuberant, corner mounts in mind.16

Figure 12-7

Figure 12-7The short front corner legs have been built up from several small blocks of oak, glued onto the post and then cut back to create the cabriole form. Beneath the front edge of the case bottom, two serpentine blocks of wood are attached, joining in the middle, to form the skirt. The central foot is attached into these blocks with a single large mortise-and-tenon joint, visible in X-ray. Diagonal cross braces attached with screws support the underside of the case bottom (see fig. 12-5); however, these do not appear to be original.

The cabinets’ bowed doors are made of laminated oak. X-radiography clearly shows that for each door, approximately fifteen narrow vertical staves are glued side by side to form the body of the door, and then substantial battens are attached to the top and bottom of the door with numerous wooden pegs and glue (figs. 12-8, 12-9). This rather unsophisticated method of assembly was also used by Dubois on the doors of his large corner cabinet made for Count Branicki (see cat. no. 11).

Figure 12-8

Figure 12-8 Figure 12-9

Figure 12-9The interiors of the doors are veneered with bloodwood. The exterior of the doors, surrounding the central lacquer panels, is veneered with fruitwood, likely pear, which serves as a smooth ground for the European black lacquer.

The cabinet doors are hung at the top and bottom on loose knife hinges that allow the doors to be lifted off of their mounts when the marble top is removed. X-ray images show that at some point in the past, possibly originally, both cabinets had third hinges in the middle of the door (screw holes are visible in the radiographs); it is not known why or at what time the third hinges were added and/or removed.

The decoration of Chinese lacquer on this pair of cabinets is extraordinary in several respects. First and foremost, it has been applied onto a markedly convex surface. The use of true Asian lacquer in this manner is extremely rare, for the simple reason that it is extremely difficult to accomplish. As has been noted previously (see, e.g., cat. no. 5), lacquer panels have a certain amount of flexibility when thinned to veneerlike thickness of approximately 1 mm. This allows them to be carefully bent in one dimension. Lacquer panels, however, have very low extensibility; that is, they cannot be stretched (or compressed) to any appreciable degree. This characteristic makes it virtually impossible to bend flat lacquer onto a compound curve without tearing or distorting the lacquer. How then was Dubois able to accomplish this extraordinary feat on these corner cabinets? The answer lies both in his technique and in his careful choice of materials.

X-radiographs of the doors reveal distinct patterns of cuts in the lacquer, which provide the first clues to Dubois’s method. The cuts show where thin wedges of lacquer were excised from the original panel, allowing it to lay flat on a convex substrate. A familiar analog might be a tailor’s technique of placing a triangular dart into a garment, allowing the textile to conform to the curves of a human form. Interestingly, the patterns of cuts on the two doors are very different. On one (cabinet .2), major cuts are made radially from the top and sides into the center of the panel (fig. 12-10). These cuts stop short of the center such that the panel remains in one piece. On the other door (cabinet .1), two major horizontal cuts split the panel into three sections and two short vertical cuts push upward from the lower edge of the upper section (fig. 12-11). The fact that the two doors were prepared in such different ways suggests that the craftsman responsible was experimenting with a technique that was not altogether routine for him. By placing a sheet of transparent polyester film (nonextensible) over the doors and making similar cuts, it is possible to determine how much of the original lacquer had to be excised to allow the lacquer to conform to the convex door fronts. This exercise also reveals that the method using radial cuts is less successful at allowing easy conformation than the other method of splitting the panel into horizontal bands. It seems likely, therefore, that the doors were prepared in that order.17

Figure 12-10

Figure 12-10 Figure 12-11

Figure 12-11Two additional points of interest are raised by the X-radiographs. The first is that the original Chinese panels do not extend to the edges of the field defined by the gilt bronze mounts. This indicates that the French craftsman responsible for lacquering the balance of the case would also have had to add significant sections of new decorative work to extend the original composition, particularly at the sides. This circumstance was presumably brought on by necessity, and therefore it seems reasonable to assume that the original Chinese panels were never significantly wider than their current maximum width of approximately 50 cm. It is also clear that the excision of original lacquer material during the bending process would have required the cuts to be hidden and any mismatches of design across the seams to be corrected by the French lacquerer as well. This is most clearly in evidence on cabinet .2 in the area of the tree. Here, the original French retouching is visible as a 2-cm-wide band straddling the cut; the French work was executed in brass powders that have tarnished and darkened (fig. 12-12).

Figure 12-12

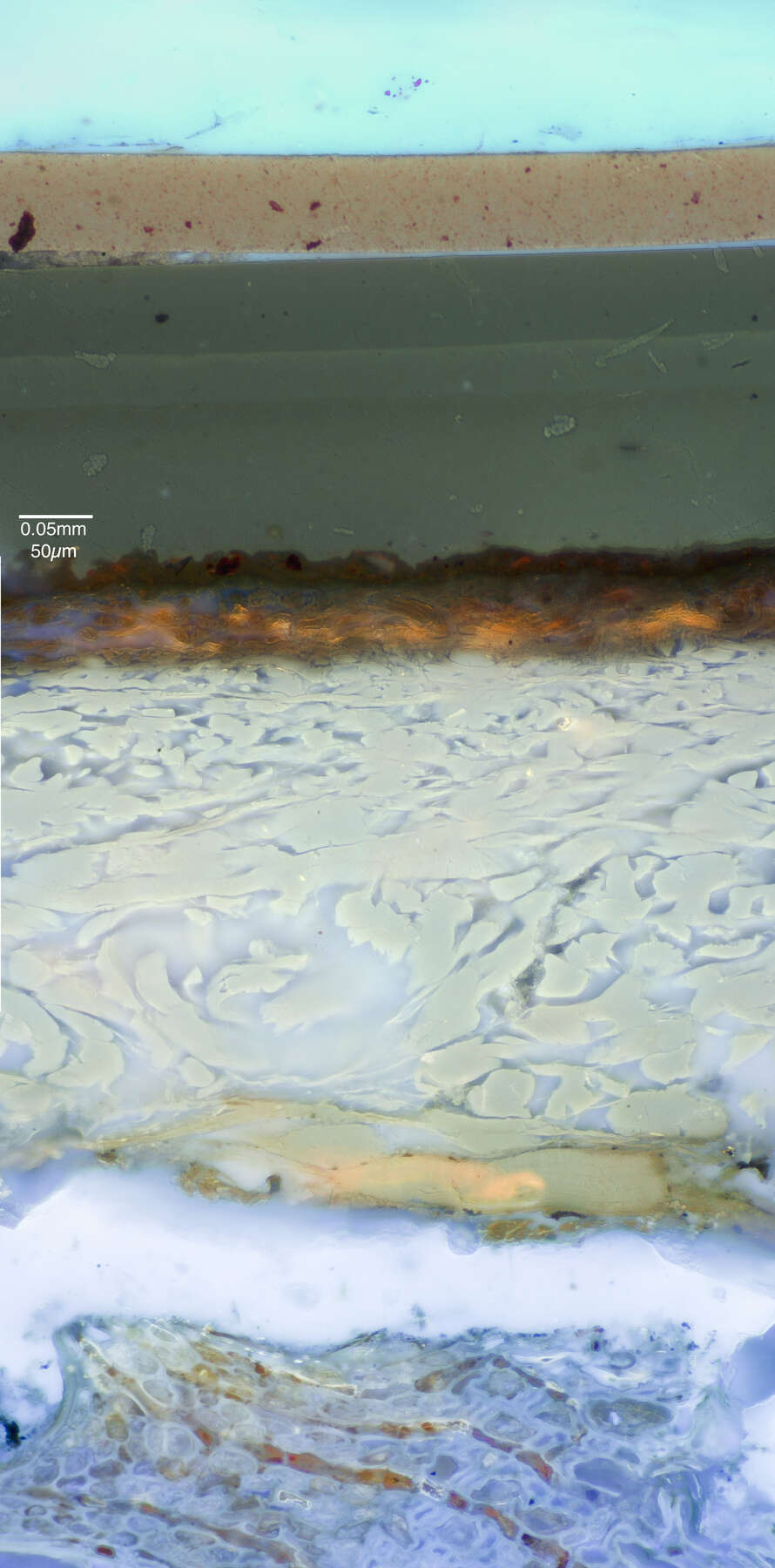

Figure 12-12Dubois’s success in bending his Chinese panels onto these doors may be attributable not only to the skill of the craftsman but also to the inherent qualities of the panels he selected. These panels are extremely unusual in that they were originally lacquered onto a leather substrate. At the time of writing, no other examples of lacquered leather are known on French furniture. This substrate would undoubtedly have been an advantage to Dubois as he attempted this challenging compound bending technique. Wood (the preponderant substrate for lacquer) has a distinct grain direction, and as a result, a panel of lacquer on wood will bend more readily in one direction than the other. Leather, on the other hand, is essentially isotropic, without any inherent directional structure, allowing these panels to bend with equal ease in any direction. Using the analytical technique peptide mass fingerprinting, the leather substrate used for these panels was identified as deriving from a water buffalo.18 This finding aligns with the sixteenth-century Chinese text “Xiu Shi Lu,” which states that water buffalo hide was the preferred leather type for lacquer.19 The relative thinness of the leather used in these panels (cross sections show it is about 0.4 micron thick) suggests that the hide was likely thinned (figs. 12-13, 12-14).20 Due to the leather substrate, the ground layers of this lacquer have also been prepared differently from other examples of Chinese lacquer in the Getty collection (see cat. nos. 5, 13). Whereas examples on wood contain multiple thick protein-bound ground layers with paper intermediate layers, the lacquer on this object was applied over a thin ground layer measuring only 20 microns in thickness. Based on scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) analysis, this layer appears to contain clay with an inorganic composition similar to that found in typical Chinese export grounds. Another advantageous characteristic of these panels lies in the composition of the lacquer. The lacquer used for these panels was originally mixed with large amounts of drying oil, which may have resulted in a dried film of enhanced flexibility. While the addition of drying oil is relatively common among the Asian lacquer panels studied, the drying oil used in this object appears to have been heat bodied.21 Heat bodying of drying oils in China consisted of heating the oil to a very high temperature. Based on the examples studied at the Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum up to the time of writing, heat-bodied oils appear to have only been used in Chinese lacquer objects; they have not yet been identified in Japanese examples.

Figure 12-13

Figure 12-13 Figure 12-14

Figure 12-14Analysis by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (py/GC-MS) shows that the lacquer can be classified as laccol lacquer, which originates from the tree Toxicodendron succedaneum. While this lacquer is commonly known as Vietnamese lacquer, the tree’s range extends into southern China and would have been available to Chinese artisans.22 In addition to drying oil and lacquer, samples from the two black lacquer layers are also rich in laccol carbohydrates and tannins. Laccol sap is known to contain nearly three times more naturally occurring carbohydrates than urushi.23 The tannins detected likely also relate to those naturally occurring in laccol lacquer.24 The lower lacquer layers also have small amounts of cedar oil; this material is commonly found in eighteenth-century Chinese export lacquer, though it is not mentioned in the Chinese literature and its function in the lacquer mixture is not currently known.25 The red lacquer used as a mordant for the gold powder decoration has a similar composition to the transparent lacquer, as it contains laccol lacquer, laccol carbohydrates, tannins, and drying oil but with the addition of an iron-based red colorant.

The original source of the Chinese lacquered leather panels is rather enigmatic, and little has been published to indicate from what type of object such panels might derive. Perhaps the most likely source would be a leather-wrapped folding screen, a leather-bound traveling chest,26 or a document box, but for now this must remain a subject of speculation.

Unfortunately, as mentioned in “Commentary” above, the majority of the Asian lacquer has been overpainted. This restoration work, though skillfully executed, obscures most of the original decorative surfaces. The only areas that appear to be essentially free of overpaint are the foliage of the trees and the face and horse of the emperor.

Beyond the bounds of the Chinese panels, the cases of the cabinets were decorated in European black lacquer.27 Ultraviolet and electron microscopy along with py/GC-MS analysis show that the original European lacquer was built up in three primary layers. First, a foundation of an organic black pigment, probably lampblack, was applied. This would have been a relatively inexpensive pigment with a slightly warm tone. This pigment was bound in a spirit-resin varnish based on pine resin, sandarac, and possibly a small portion of shellac.28 This combination of soft pine resin and harder sandarac would have allowed the finish to be tough and elastic, yet hard enough to polish. A small amount of shellac may also have been added to further increase the hardness of the layer. Starch was also detected in this layer and may relate to the use of a size to prepare the wood substrate.29 After the initial pigmented layer, a coat of bone black, which was more expensive but could produce a deeper and truer black, was applied, followed by a final transparent varnish layer. The bone black layer and the final transparent varnish were bound in a similar medium to that seen in the first layer; however, camphor was also detected in the transparent layer. Jean-Félix Watin notes that camphor could be added, in small amounts, to spirit varnishes to improve their working properties:

Le camphre est une résine légère . . . qui ne sert dans le Vernis à l’esprit-de-vin que pour le rendre liant, l’empêcher de gerser, mais il faut en mettre peu.

[Camphor is a very light resin . . . that only serves in spirit varnishes to render them smooth, prevent them from wrinkling, but it is necessary to add only a little.]

This may explain its addition in the final finish layer.30

The interior of the cabinets is in brilliant red European lacquer. This conceit is probably derived from Japanese lacquer cabinets of the seventeenth century whose black and gold exteriors were commonly complemented by red or green interiors. In this case the original European lacquer was built up in two primary layers; a ground of vermilion adulterated (knowingly or not) with red lead and sealed with transparent varnish. The medium for both layers seems to have been nearly identical, containing pine resin, a polycommunic diterpenoid resin (possibly sandarac or soft copal),31 and a drying oil. It may be that a small amount of shellac was also added to these layers, though the analytical results are not conclusive on this subject. Likewise, the analysis seems to indicate that beeswax, as well as a larger amount of drying oil, is present in the lower layer; however, with no known recipes of the period calling for beeswax to be mixed into a varnish, it is possible that this represents a contaminant in the sample from a later restoration treatment. Both the interior and the exterior European lacquers have been restored with several campaigns of paint and/or varnish (fig. 12-15).

Figure 12-15

Figure 12-15The gilt bronze mounts on these corner cabinets are no less a virtuoso performance than the bent lacquer panels. The mounts on the doors surrounding the lacquer were originally single frames, assembled from numerous small castings by skillful soldering. Standard practice of the period would have called for the individual castings to have been mounted separately, hiding the joints as well as possible through careful mechanical fitting and overlapping. In this case, however, Dubois appears to have taken the opportunity to display the skill of his bronzier by successfully overcoming the technical difficulties inherent in creating a unified frame on this scale. Soldering multiple sections of cast brass32 together to form larger mounts was always a challenging task. The sections had to be held in perfect alignment while the area to be joined was placed in the center of a charcoal furnace or otherwise surrounded by hot coals. Small clippings of solder mixed with flux were placed over the joint, and the joint area was brought to a cherry-red heat (approximately 920°C) until the solder melted and flowed into the joint. The danger was that if the joint was overheated, the castings themselves could melt, ruining the mount entirely. The soldering metal used was typically brass with a higher zinc content (and thus lower melting point) than the metal to be joined. In practice, however, the difference in melting points could be as little as 50°C, and overheating was a serious concern. In order to reduce the potential for accidental melting in these mounts, Dubois’s bronzier chose an unusually high-zinc brass for his solder (about 37% zinc as determined by X-ray fluorescence [XRF] analysis) while keeping the zinc content of the casting metal relatively low (about 16% by XRF) in order to maximize the difference in their melting points.33 Such high-zinc soldering metal was a specialty product that could not be produced by the conventional brass-making technology of the day. It relied for its manufacture on costly and imported metallic zinc, and its documented use in French furniture is rare, though period sources do discuss its use.34

Another significant difficulty with producing single large mounts on this scale was in controlling their final shape so that they would fit perfectly the complex curved surface of the corner cabinets’ doors. To achieve this goal, every soldered joint had to be in near-perfect alignment, as any attempt to bend the frame after assembly would risk cracking the joints. Perfect alignment would have been particularly crucial and also particularly difficult in the final stages when the loop was to be completed. In order to fix the position of his sections with great precision during the final soldering operations, Dubois’s bronzier resorted to an ingenious trick. Once the upper and lower halves of the frames had been assembled, he drilled two small holes on either side of the last joints to be welded. He then looped copper wire through the holes and twisted it to pull the joints tightly together, fixing the position of the sections securely so that they could be soldered without shifting. The remnants of the wire, surrounded by solder, are still visible (figs. 12-16, 12-17).

Figure 12-16

Figure 12-16 Figure 12-17

Figure 12-17The framing mounts on the doors also show evidence of having been modified somewhat from their original design. At the bottom of each mount, on either side of the central C-scroll arrangement, there is a section of unadorned molding that has been lengthened by adding a short section of metal, about 4 cm long. These sections of metal (two on each cabinet) are not sand cast like the other sections of the mount but rather are cut and filed from solid blocks of brass. This suggests that the original model for the framing mounts tapered somewhat toward the bottom but that for this particular pair of cabinets, the design was altered to render it more rectangular in form. The Quirinale cabinets (see “Commentary” above and fig. 12-3) appear to have the door mounts in their unaltered form.

Quantitative XRF spectrometry of eighteen representative casting sections from the cabinets’ mounts reveals that the alloy of the mounts is typical in all respects of French eighteenth-century casting brass. The composition of the metal used for the framing mounts on the doors is so uniform that the mounts were almost certainly cast from a single batch of molten metal. The narrow plain moldings running between the legs along the lower edge of the skirt appear to have been replaced on cabinet .2; confirmation of this by alloy analysis was not possible as the moldings were too small to be analyzed with the XRF instrument at hand.

The cabinets’ mounts have been gilded with leaf gold, not by traditional amalgam gilding. Lap lines and folds in the leaf are visible in areas of wear since the gold here is of double or triple thickness. Little written evidence from the eighteenth century exists to explain how the technique was carried out in the period. D’Arcet, in 1818, briefly mentions that the technique passed out of use some fifty years earlier and that it involved “applying the leaves of gold on the bronze whitened by means of mercury.”35 XRF analysis confirms that there is mercury present in the gilding layer of these mounts. This method may have been chosen for these mounts because it required less heating of the mounts than conventional amalgam gilding and therefore presented less risk of damaging the multiple soldering joints on the delicate frames.

The cabinets’ marble tops are approximately 2.5 cm thick and are made of brèche d’Alep, a heterogeneous marble consisting of multicolored, somewhat rounded cobbles in a beige to orange sand and gravel matrix. The predominant color of the cobbles is from tan to cream, although red and even black cobbles are found as well. Many similar limestone breccias of this type occur in varying colors throughout the Mediterranean. The original Alep Breccia is from Syria. This stone, however, is thought to have been quarried in Le Tholonet, Bouches-du-Rhône, France. Although the quarry is inactive now, it had been in use since ancient times.

- A.H.,

- J.C.,

- M.S.,

- and R.S.

Notes

For more information on Jacques Dubois, see , 168–75; , 42–59; , 283–91. ↩︎

, 136–40, no. 9. They bear the marks of the Palazzo Colorno. ↩︎

Bequest of Forsyth Wickes, acc. no. 65.2513. , 317–18, cat. no. 30. ↩︎

Galerie Charpentier, Tableaux anciens et modernes, objets d’Extrême-Orient, haute époque, bel ameublement du XVIIIe siècle, May 28, 1954 (Paris: Galerie Charpentier, 1954), lot 137. ↩︎

Acc. no. OA 6083. , 158–61, no. 48; , 258, no. 82. ↩︎

Sotheby’s, The Patiño Collection: Important French Furniture and Decorations, German and Chinese Export Porcelain, European Tapestries and Carpets, November 1, 1986 (New York: Sotheby’s, 1986), lot 114. ↩︎

, 170. ↩︎

J. Paul Getty Diary, July 1–December 5, 1950, September 18, 1950, 59. Getty Research Institute, IA40009. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/cifaia40009. ↩︎

The undated note claiming that the corner cupboards were previously in the collection of Nathaniel von Rothschild is typed on an envelope along with other cataloguing information. ↩︎

I am grateful to Gerald Stiebel for his assistance in this matter. Correspondence with the author, April 7, 2005, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

, 151. ↩︎

Either the marble slabs were wrongly described in the catalogue or they were replaced between 1946 and 1950. The corner cupboards now carry slabs of brèche d’Alep. Christie’s, Old French and English Furniture and Porcelain, the Property of the Right Hon. the Earl of Wemyss and March, and removed from Gosford House, Longniddry, East Lothian, March 7, 1946 (London: Christie’s, 1946), lot 99. ↩︎

Handwritten note in a copy of Christie’s, Old French and English Furniture and Porcelain, the Property of the Right Hon. the Earl of Wemyss and March, and removed from Gosford House, Longniddry, East Lothian, March 7, 1946 (London: Christie’s, 1946), in the collection of the Getty Research Institute library. ↩︎

Correspondence between Gerald Stiebel and the author, April 7, 2005, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

Correspondence between Gerald Stiebel and the author, April 7, 2005, in the files of the Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

There is no evidence to suggest that the current mounts are not original; see discussion below. ↩︎

For additional information on bending Asian lacquer, see . ↩︎

The leather was identified by Dan Kirby Analytical Services utilizing peptide mass fingerprinting, which involves the enzymatic digestion of proteins followed by matrix assisted laser desorption-ionization time of flight mass spectrometric (MALDI) analysis of the resultant peptide mixture. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 636, shows a reference sample of tanned water buffalo hide with a total thickness of 1.6 mm and a grain to corium ratio of approximately 1.6. See for additional information on leather structure and processing. ↩︎

The processing of heat-bodied oil may be indicated by the presence of a class of compounds known as methyl alkylphenyl alkanoates (APAs). These compounds are formed from highly unsaturated linolenic acid and elostearic acid by bodying linseed, perilla, or tung oils at elevated temperatures. See . ↩︎

The py/GC-MS analysis also demonstrated that the lacquer used was derived from Toxicodendron succedaneum, the so-called Vietnamese lacquer tree, which appears to have been used extensively in China. This is contrary to the conventional wisdom, which holds that Chinese lacquer is made from the sap of Toxicodendron vernicifluum. The analysis also revealed that the oil used was probably rapeseed oil and that the leather was vegetable tanned. For details, see the organic analysis reports by Michael Schilling and Herant Khanjian on file in the Decorative Arts and Sculpture Conservation Department, J. Paul Getty Museum. ↩︎

. ↩︎

Laccol sap tapped from a Toxicodendron succedaneum tree growing at the Los Angeles Arboretum was found to contain tannins. See , 17. ↩︎

, 35. ↩︎

Lacquered leather trunks (malle in French) with tops as large as 105 x 53 cm were in regular production in Canton in the first half of the nineteenth century (, 125–26), but their production in the mid-eighteenth century has not been confirmed. ↩︎

See “The Analysis of East Asian and European Lacquer Surfaces on Rococo Furniture,” in this volume. ↩︎

Based on interpretation challenges noted in “The Analysis of East Asian and European Lacquer Surfaces on Rococo Furniture,” in this volume, it is difficult to definitely exclude the use of soft copal in this lacquer. ↩︎

, 136–37. ↩︎

, 208. ↩︎

The mounts are technically brass, an alloy primarily of copper and zinc; see “Technical Note.” ↩︎

This difference in alloy composition yields a difference in melting point of approximately 125°C (). For details of the analysis methodology, see “The Use of X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF) in the Technical Study of Gilt Bronze Mounts,” in this volume. ↩︎

A recipe for soldering metal nearly identical to this is given on p. 35 of Jean-Gaffin Gallon, L’Art de convertir le cuivre rouge ou cuivre de rosette en laiton ou cuivre jaune (1764), in Henri Louis Duhamel de Monceau, Descriptions des arts et métiers (1767), vol. 11. ↩︎

. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Alcouffe, Dion-Tenenbaum, and Lefébure 1993

- Alcouffe, Daniel, Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, and Amaury Lefébure. Furniture Collections in the Louvre. Vol. 1, Middle Ages, Renaissance, 17th–18th Centuries (Ébénisterie), 19th Century. Dijon: Éditions Faton, 1993.

- Arcet and Sève 1818

- Arcet, Jean-Pierre-Joseph d’, and Jacques Eustache de Sève. Mémoire sur l’art de dorer le bronze: Ouvrage qui a remporté le prix fondé par M. Ravrio et proposé par L’Académie royale des sciences. Paris: De l’imprimerie de Mme Veuve Agasse, 1818.

- Boiron 1990

- Boiron, Stéphane. “Jacques Dubois, maître de style Louis XV.” L’Estampille/L’Objet d’Art 237 (June 1990): 42–59.

- Bremer-David et al. 1993

- Bremer-David, Charissa, et al. Decorative Arts: An Illustrated Summary Catalogue of the Collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1993.

- Durand 2014

- Durand, Jannic, ed. Decorative Furnishings and Objets d’Art in the Louvre. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2014.

- Getty and Le Vane 1955

- Getty, J. Paul, and Ethel Le Vane. Collector’s Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe. London: W. H. Allen, 1955.

- Getty 1963

- Getty, J. Paul. Chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection J. Paul Getty. Monaco: Jaspard, Polus et Cie, 1963.

- Getty 1965

- Getty, J. Paul. The Joys of Collecting. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1965.

- Getty 1956

- Getty, J. Paul. “Vingt mille lieues dans les musées.” Connaissance des Arts 57 (November 1956): 76–81.

- Gillett and Norton 1913

- Gillett, H. W., and A. B. Norton. 1913. “The Approximate Melting Point of Some Commercial Copper Alloys.” Chemical Engineer 18 (4): 167–70.

- González-Palacios 1996

- González-Palacios, Alvar. Il patrimonio artistico del Quirinale, gli arredi francesi. Milan: Electa, 1996.

- Hagelskamp, Heginbotham, and van Duin 2016

- Hagelskamp, Christina, Arlen Heginbotham, and Paul van Duin. “Bending Asian Lacquer in Eighteenth-Century Paris: New Discoveries.” Studies in Conservation 61, suppl. 3 (2016): 91–96.

- Heginbotham et al. 2016

- Heginbotham, Arlen, Julie Chang, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling. “Some Observations on the Composition of Chinese Lacquer.” Studies in Conservation 61, suppl. 3 (2016): S28–S37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2016.1230979.

- Huth 1971

- Huth, Hans. Lacquer of the West: The History of a Craft and an Industry, 1550–1950. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

- Kite and Thomson 2006

- Kite, Marion, and Roy Thomson. Conservation of Leather and Related Materials. Boston: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006.

- Kjellberg 1989

- Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle: Dictionnaire des ébénistes et des menuisiers. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989.

- Kumanotani 1995

- Kumanotani, J. “Urushi (Oriental Lacquer): A Natural Aesthetic Durable and Future-Promising Coating.” Progress in Organic Coatings 26 (1995): 163–95.

- Munger 1992

- Munger, Jeffrey H., et al. The Forsyth Wickes Collection in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992.

- Pradère 1989a

- Pradère, Alexandre. French Furniture Makers: The Art of the Ébéniste from Louis XIV to the Revolution. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1989.

- Rondot, Hedde, and Haussman 1849

- Rondot, Natalis, Isodore Hedde, and A. Haussmann. Étude practique du commerce d’exportation de la Chine. Paris: A la Libraire du Commerce, Chez Renard, 1849.

- Schilling et al. 2014

- Schilling, Michael, et al. “Chinese Lacquer: Much More Than Chinese Lacquer.” Studies in Conservation 59, suppl. 1 (2014): 131–33.

- Schilling et al. 2016

- Schilling, Michael R., Arlen Heginbotham, Henk van Keulen, and Mike Szelewski. “Beyond the Basics: A Systematic Approach for Comprehensive Analysis of Organic Materials in Asian Lacquers.” Studies in Conservation 61, suppl. 3 (2016): 3–27.

- Walch 1997

- Walch, Katharina. “Baroque and Rococo Transparent Gloss Lacquers: I. The Replication of White Lacquers on the Basis of Historic Sources and Scientific Examination” and “Baroque and Rococo Red Lacquers: The Red Lacquer-work in the Miniaturenkabinett of the Munich Residenz. Replicating the Technique on the Basis of Historic Sources and Scientific Inverstigation.” In Lacke des Barock und Rokoko = Baroque and Rococo Lacquers, edited by Katharine Walch and Johann Koller, 21–52 and 129–44. Munich: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, 1997.

- Wang and Huang 2004

- Wang, S., and C. Huang. Xiu shi lu. Beijing: Zhongguo ren min da xue chu ban she, 2004.

- Watin 1778

- Watin, Jean-Félix. L’art du peintre, doreur, vernisseur: Ouvrage utile aux artistes et aux amateurs qui veulent entreprendre de peindre, dorer et vernir toutes sortes de sujets en bâtimens, meubles, bijoux, equipages par Jean-Félix Watin avec la collaboration de Roch-Henri Prévost de Saint Lucien. Liège: D. de Boubers, 1778.

- Wescher 1955

- Wescher, Paul. “French Furniture of the Eighteenth Century in the J. Paul Getty Museum.” Art Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1955): 115–35.

- Wilson 1941

- Wilson, Arthur. Modern Practice in Leather Manufacture. New York: Reinhold, 1941.

- Wilson and Hess 2001

- Wilson, Gillian, and Catherine Hess. Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.

- Wolvesperges 2000

- Wolvesperges, Thibaut. Le meuble français en laque au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2000.

| words