1. Biological Material Indeterminacy Rebukes the Social and the Artistic: Cases from the Documentary Archives of the Arkheia Documentation Center, Mexico

- Eugenia Macías

- Cristina Reyes

Some of the items held at the Centro de Documentación Arkheia of the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) exemplify unusual artistic uses of diverse biological material that distort received canons of art. This paper discusses works by Santiago Rebolledo, Rocío Boliver (also known as “La Congelada de Uva”), and César Martínez Silva that alter the concept of archive and documentary resource through the presence of biological components and their precarious, indeterminate status in terms of material permanence. In these cases the role of the archivist is productive, as proposed by Hal Foster (, 31–35) and Anna María Guasch () and revised and paraphrased by Andrés Maximiliano Tello (), who imagine the paradigm of archiving as a sort of uncertain, fragmentary, and playful memory in which human testimonies provide a foundation for proposing critical art practices.

Santiago Rebolledo: A Living Process

El Archivero was a gallery and bookshop active from 1985 to 1991 in the Colonia Roma neighborhood of Mexico City. It started as a project to promote dissemination, distribution, and collaboration in publishing within the artist’s book movement. It arose from the passion for experimentation and self-publishing that Felipe Ehrenberg brought from England in the early 1970s with the Beau Geste Press / Libro Acción Libre publishing community, which had survived over subsequent generations. This is also how Agru-pasión entre Tierras was born, a sort of traveling publishing company founded by Santiago Rebolledo, René Freire, Manuel Zavala, Ana Checchi, Diego Mazuera, Elsa Zambrano, Gabriel Macotela, and Paul Rolfe.

This publishing company was specifically created for mail art and thus began to collaborate with El Archivero. One of these collaborations was Hoja de vida / El Cabello está en la cabeza (Résumé / Hair Is on the Head, 1985, fig. 1.1) by Rebolledo, a coauthored book consisting of a wooden shoeshine box with cutouts of photos, coins, and other metal objects adhered to its exterior. Inside the box is a large piece of parchment that unfolds to reveal repetitions of the typewritten phrase “El Cabello está en la cabeza,” accompanied by hanks of hair from different artists, along with their signatures.

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1The making of this piece occurred in stages that are worth revisiting, as they represent relevant and significant activations, or diffusion events of public circulation. The piece originated with a sheet of paper that Freire found on the street. He thought the phrase it bore was interesting and mailed it to Rebolledo, who at that time was living in Colombia. Some time later, Rebolledo returned to Mexico, bringing Freire’s letter with him. At a gathering at Macotela’s home, Freire and Macotela made a mimeograph stencil of the phrase and printed it repeatedly on a large piece of Kraft paper.

Rebolledo proposed an intervention into this sheet of paper by inviting several attendees to cut a lock of their hair, glue it to the paper, and sign it, after which they released the parchment out a third-floor window of the building. The paper fell to the street. It seems that part of the sheet was lost in this action, and what remains is slightly less than a meter in length (fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2This account, constructed in April 2019 from memories and electronic communications between Rebolledo, Freire, and another friend of their generation, the photographer Armando Cristeto, is a clear example of how the works these groups published were not simply printings on paper, but artworks that included the actions that led to them. The hair stored in the box is evidence of a living process that is undergoing change even now (fig. 1.3).

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.3Rocío Boliver, “La Congelada de Uva”: I’m happily living my slogan, “LET ME SHOW YOU”

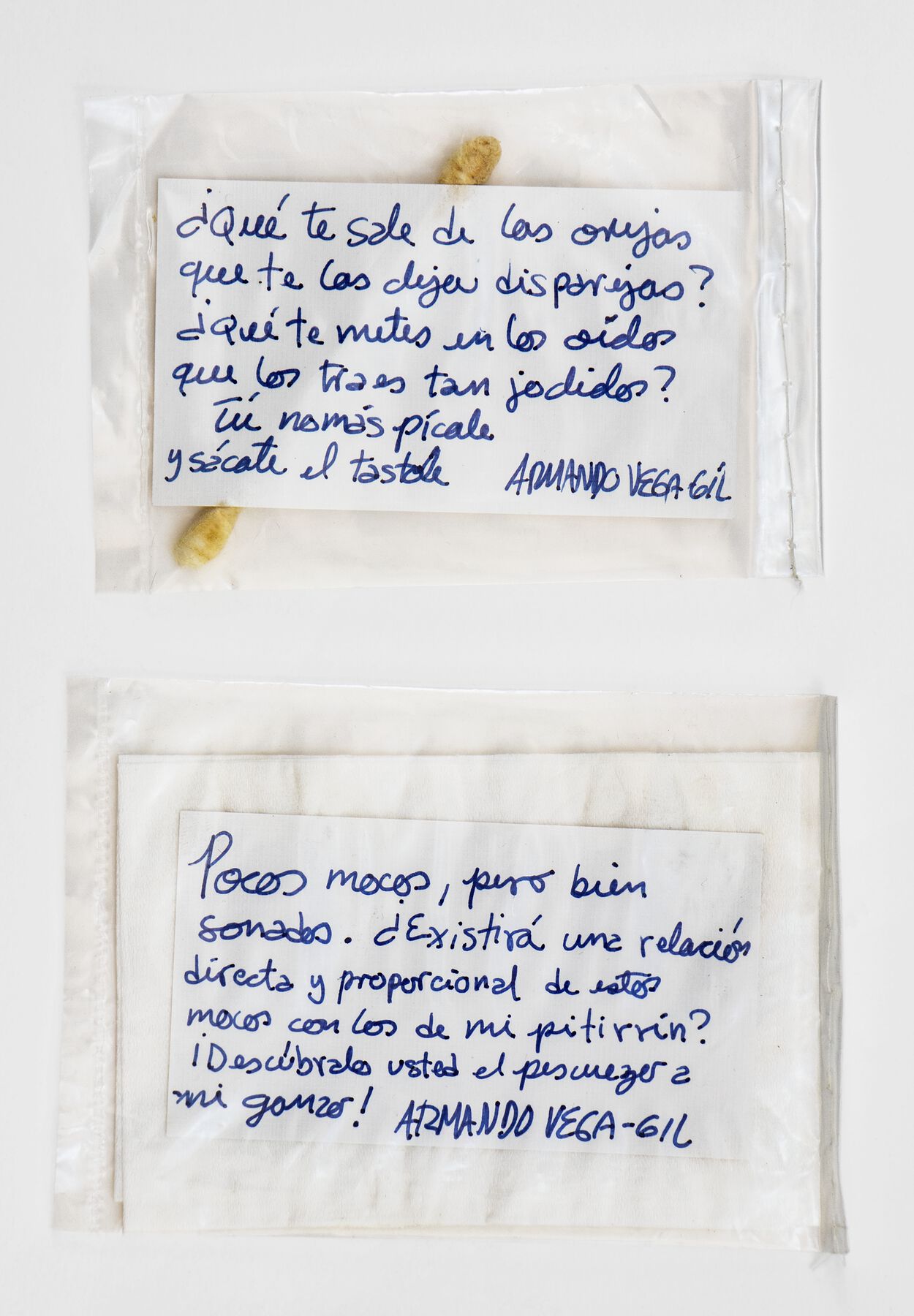

Pocos mocos (Little Snots, ca. 1999, fig. 1.4, fig. 1.5, fig. 1.6) is a collection of packets, each containing a commercial cotton swab, disposable tissue, paper, earwax, and nasal mucus from the maker’s artist friends. What slightly mitigates the instinctive reaction of disgust is the range of responses on the notes accompanying each bag: drawings, phrases, texts, other objects. The creator of this project is Rocío Boliver, also known as “La Congelada de Uva” (The Grape Popsicle), who has a long history of performances and other actions involving the handling of human fluids.

Figure 1.4

Figure 1.4 Figure 1.5

Figure 1.5 Figure 1.6

Figure 1.6One may wonder sometimes whether the exercise of provocative intellectual argumentation by critics carries more weight than an action itself, which borders on excess. However, we find useful Fabián Giménez Gatto’s problematization of the pornographic aspects in Boliver’s work. In an article on her obscenity and trans-aesthetic games published in 1999 at the Uruguay-based site H Enciclopedia, Gatto suggests that the elements of her actions are expressive units (which he calls pornograms) that provide two processes, or lenses, by which we can assess Pocos mocos: the link between the body and inscriptions with, from, on, and in it, and the breaking of the boundary between what is inside an artistic situational framework and what is outside of it. He describes it as an obscenity seeking an enormous immersion or nesting within the observer, to the point of being unrepresentable because it is beyond all limits, because the experience is placed on a chaos of scales, making it hard to find any dimension of weight between the components of certain actions and the world of reference (broad or limited) of the person contemplating them. It is an experience that Boliver expressed with the phrase: “I’m happily living my slogan ‘LET ME SHOW YOU’” ().

Sol Henaro, Alejandra Moreno, and Christian Aravena deserve acknowledgment for recommending texts and providing an oral account of this project by Boliver. These three, along with Brian Smith, were the curators of an exhibition that opened in 2019 at the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC), Arte acción en México: Registros y residuos (Action Art in Mexico: Registers and Residues). This exhibition brought together—under various reflexive criteria—the documentary records of projects along this creative line in Mexico and included Pocos mocos in the group “Salir de la carne: Prótesis y accesorios” (Out of the Flesh: Prostheses and Accessories), which sought to emphasize works that expand the usual perimeters of bodily experience (, 12, 13).

In an oral account Boliver provided regarding this project in November 2018, she stated that she requested mucus from fellow artists, and supplied packets in which they could deposit their secretions along with a comment. Juan José Gurrola gave her a scab and a fingernail; Felipe Ehrenberg was happy to oblige, but Astrid Haddad was not; Guillermo Fadanelli proffered only colored sprinkles.

At that time, Boliver had recently seen an installation at ExTeresa in Mexico City by an unidentified foreign artist consisting of little labeled plastic bags containing such things as river water from Spain, Japan, and Mexico—all apparently alike—and rose petals from India, Chile, and Canada—again, all seemingly identical. It occurred to her to take the idea to an abject extreme, suggesting that artists and non-artists all have similar mucus and earwax. Broach what is private and flaunt it. One does not extract these excretions in public (or if one does, there are social protocols). It also aligned with other performances in which she used her own excretions: tears, eye discharge, mucus, excrement, urine, menstrual and other blood, saliva, and phlegm.

Conservator Alexandra Samkova performed basic conservation treatments on the material record of this project when Boliver’s documentary archives entered the MUAC in 2017 and were added to the Centro de Documentación Arkheia. She stated in an interview at the museum in November 2018 that she only stabilized each unit (examining and registering its conservation condition, and transferring the group to preservation covers and cases) and repacked it, since the packets were all part of the devised system that Boliver had created to gather the materials. Samkova said that it would be intriguing from a conservation perspective to conduct a physical and chemical analysis of each one to determine whether it contained latent biological activity, and thus whether other storage or preventive isolation methods might be called for.

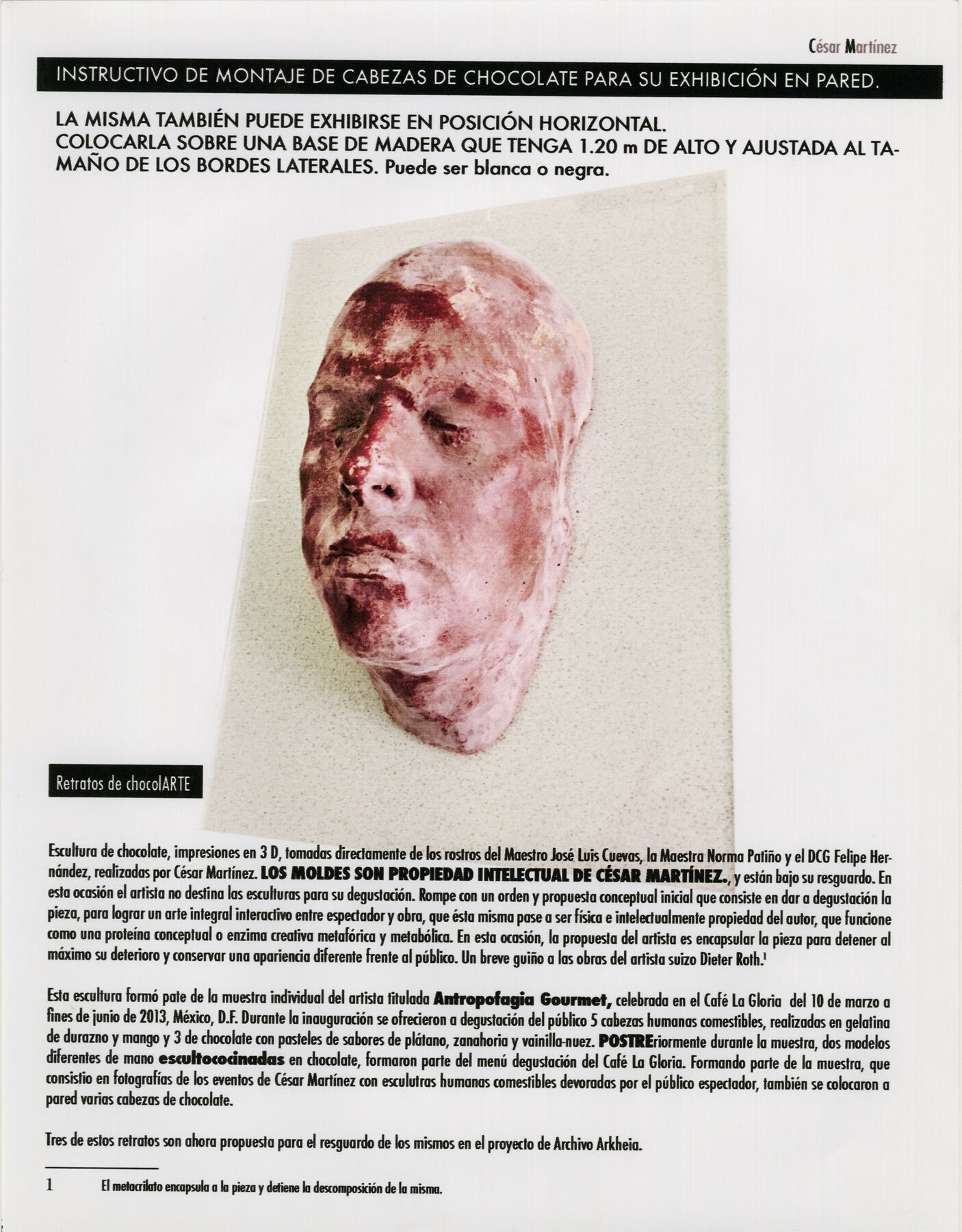

César Martínez Silva: Retratos de chocolARTE, or the Ephemeral as Future Condition

Retrato de chocolARTE (Portrait in ChocolART, 2013, fig. 1.7) is one of three faces 3D printed in chocolate by César Martínez Silva and first presented in the 2013 solo exhibition Antropofagia Gourmet at Café La Gloria, Mexico City (fig. 1.8). This work exemplifies one of the fundamental ideas behind Martínez Silva’s processes: the ephemeral transformed into a future condition, or how conceptual artistic practices can generate as much or more meaning than an artwork’s material permanence. Some of Martínez Silva’s chocolARTE works are completed when they are devoured, or at least tasted, by people in situations arranged by the artist, as a critique of certain unconscious ethical-political stances on humanity; for instance some persons attending Martínez Silva’s performances with chocolate in human form become actors in symbolic anthropophagic actions.

Figure 1.7

Figure 1.7 Figure 1.8

Figure 1.8But this piece, produced along with two others and based on the faces of Norma Patiño, Felipe Hernández, and José Luis Cuevas (this information comes from the artist; we are not sure who these people are except for the famous artist Cuevas), emanates from another conceptual event recounted by Martínez Silva in an email message from May 2019: isolate chocolate faces in jars made of acrylic plastic to decelerate the process of biodegradation and oxidation, and then encourage their contemplation not by eating but by dislocating or diverting from the primary function of ingestion toward vision alone (to eat with one’s eyes?).

The artist engages in a dialogue with the premise of conservation by having an exhibition of his work simultaneously display elements made to be eaten and others made from foods but mounted on a wall to be observed and protected from environmental conditions that might accelerate their deterioration. The system for securing the pieces to the wall posed a challenge. The chocolate is not fastened directly to the acrylic jars, but is hollow, with a wooden core that anchors it to the container. Martínez Silva prepared detailed instructions for mounting them.

In her recent research into the work of Martínez Silva, the art historian María Luisa González proposed that his projects activate transubstantiations of sociopolitical critique and behaviors restored in the performance space itself. They re-signify acts, discourses, objects, and cultural products drawn from religious ritual practices having to do with the transformation and/or transubstantiation of matter, and with the artist’s own unsettled relationship with his Catholic upbringing (). Furthermore, by alternately allowing either ingestion or observation of the portraits in Retratos de chocolARTE, Martínez Silva makes it possible to enter and exit the situation of anthropophagy, as he has done in other installations, such as an event-exhibition in Santander, Spain, in 2015, which also included pieces of chocolate (fig. 1.9) and built another alternative to the spiritualization of matter. González refers to this interpretation via a comparison to the writer Nikos Kazantzakis’s conception of transubstantiation. For González, these entreaties to specific means of contemplation (eating and/or observing) also bring about changes in the status of the individual participants as they reflect on themselves and what they have experienced, similar to the way Richard Schechner links ritual performativity and aesthetics.

Figure 1.9

Figure 1.9Martínez Silva himself recently reflected on this in a dialogue with contemporary art conservation scholars regarding his approach to the case of artist Dieter Roth (countering the restorers’ logic of material preservation), concerning another sculptural trend in his work—works in latex—that can be extrapolated to the sculptures in chocolate (). And in a 2018 email exchange with these authors, Martínez Silva stated, “The ethereal, the fleeting, the invisible, the imperceptible, the perishable, the momentary, the fugitive, and passing are the subjects of my research and, therefore, the very basis of my sculptures. . . . They were envisioned as events, situated in a concrete space/time dimension, not to be understood as concrete, sculptural objects of art.”

In this line of work, Martínez Silva plays with encounters between physical properties of materials and their conceptual auras, willingly assuming the risk of accidents that accompany the passage of time. For this artist, such risks provide new paths—his strategies for documenting visual accounts of damage to the pieces and their material degradation correlate with their sociopolitical meanings. They have also led him into scientific research into materials, as in the case of his pieces in latex. Such research is still pending for his pieces in chocolate, exploring the improbability that gives life to the long lasting.1

Conclusion

This overview of three specific cases reveals the dilemmas concerning the role of organic or biological matter in artwork as it pertains to material preservation as a means of protecting the historical memory of artistic practices of dissent; and also ethical dilemmas that the projects themselves actuate through organic matter, for instance sublimated cannibalism and anthropophagy, or abject or scatological intimacy.

Hoja de vida / El Cabello está en la cabeza is just one of many pieces to emerge from a generation that decided it did not need fine paper or professional printing systems to create art. A shoeshine box, hair, and glued cutouts are testimony that the artist’s book movement would not simply begin or end with the printing of a book, thus calling into question the common conception of the archive and its conservation.

In Pocos mocos, biological waste plays a leading role in the disruption of what might be considered artistic or worthy of collection. Its current storage arrangement raises various conservation issues: Is a microclimate operative in each plastic bag such that the organic material is undergoing deterioration or other behaviors? Would it be preferable to transfer each unit to more stable storage arrangements, even if it entails replacing the original artist-created packets?

In the sculptural approach envisioned in Antropofagia Gourmet, on the one hand samples of processed animal milk are eaten in an elegant banquet attended by the artist and the public, which, if the faces were real, would be a cannibalistic act. At the same time, the busts of chocolate are exhibited as hunters might display mounted animal heads. The organic matter evokes community rituals in traditional cultures in which the purpose of collective participation is to make a connection through rites, food, masks, and accessories.

Notes

César Martínez Silva, email message to the authors, November 2018. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Foster 2015

- Foster, Hal. 2015. Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency. London and New York: Verso.

- Giménez Gatto 1999

- Giménez Gatto, Fabián. 1999. “Obscenidad a la mexicana: Los juegos transestéticos de Rocío Boliver (I y II),” H Enciclopedia, http://www.henciclopedia.org.uy/autores/FGimenez/Obscenidad1.htm, http://www.henciclopedia.org.uy/autores/FGimenez/Obscenidad2.htm.

- González 2018

- González, María Luisa. 2018. “La transubstanciación. El performance en el performance. Un abordaje a La perforMANcena, ‘North America Cholesterol Free Trade Agreement’ (1999) in César Martínez Silva.” In Aproximaciones interpretativas multidisciplinarias en torno al arte y la cultura, edited by Raúl Wenceslao Capistrán Gracia, 135–45. Aguascalientes, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.

- Guasch 2011

- Guasch, Anna María. 2011. Arte y archivo. Genealogías, tipologías y discontinuidades. Madrid: Akal.

- Henaro et al. 2019

- Henaro, Sol, Alejandra Moreno, Christian Aravena, and Brian Smith. 2019. Arte-acción en México. Registros y residuos. Mexico City: MUAC-UNAM.

- Martínez Silva 2013

- Martínez Silva, César. 2013. “Permanencia en el tiempo de esculturas hinchables realizadas con hule látex vulcanizado, mecanismos de aire y sensores electrónicos; La conservación del futuro.” Presentation at the 14th Jornada de Conservación de Arte Contemporáneo, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

- Maximiliano Tello 2015

- Maximiliano Tello, Andrés. 2015. “El arte y la subversión del archivo.” Aisthesis, no. 58, 125–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-71812015000200007.