16. Building Communities and Conserving Living Matter in the Collection of the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, MUAC-UNAM, Mexico City

- Claudio Hernández

The “Living Matter” symposium offered a great opportunity to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Restoration Laboratory of the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Mexico City, while also reflecting on and contributing some solutions to the problem of preserving biological materials used in contemporary art. As one of the organizers of this gathering, the museum reaffirms its commitment to the study and conservation of contemporary collections, as well as to promoting the professional training of conservators specializing in contemporary works in Mexico, in collaboration with the Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía (ENCRyM), also in Mexico City and part of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

The first collaboration between MUAC’s Restoration Laboratory and ENCRyM’s Seminario Taller de Restauración de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo (Workshop-Seminar on Restoration of Modern and Contemporary Art) was established in 2010. Since that time, a dynamic has evolved that allows for discussions with professors on conservation issues anchored in several case studies from the MUAC collections, which the students are able to address with the advice of various specialists. One of the questions the collaboration strives to answer regards how theory and practice should be combined in the conservation of contemporary art. The answer proposed: via strategic collaborations between academia and the spaces where conservation is practiced, namely museums (fig. 16.1).

Figure 16.1

Figure 16.1In this institutional collaboration, MUAC’s contributions have been to supplement student training through the case study method, thereby contributing to research on and conservation of a significant diversity of materials. The students have also followed guidelines for conducting interviews with artists and other cultural agents for the purpose of understanding the artist’s intention for each work and the material and conceptual significance of the materials used. Lastly, they come to understand how the passage of time may or may not alter a work. Through this dialogue between students and specialists, the students come to understand the needs of a public institution like MUAC, where research and intervention proposals go hand in hand with guidelines for conserving collections. Additionally, long-term accessibility is fundamental, since the entire collection belongs to the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

In the last decade, Mexican contemporary art conservators have been a very active professional group working through public and private institutions to discuss and solve issues together, and to contribute to the international scene with Mexican case studies and context. One of the main takeaways has indeed been the need to work as a professional community and broaden networks and teams, due to the characteristics and adversities in the context of Mexico’s contemporary cultural heritage and institutional complexities.

Following are two case studies from the MUAC collection in which the research, diagnosis, stabilization proposals, and conservation treatments were carried out by students and professors from ENCRyM in dialogue with other specialists and staff from the MUAC Restoration Laboratory. Note that the conservation treatments were concluded in the first case, but in the second case the treatment is still in progress.

Case Study: Marta Palau Bosch

The work of artist Marta Palau Bosch (b. 1934) is characterized by the use of organic materials such as textile fibers, handmade paper, branches, and mud, although she has also used synthetic fibers to a lesser extent. Her sculptural textiles are noted for the diversity of their subjects (migration, myths, femininity) as well as their excellent manufacture and concern for material significance. Historian Jorge Alberto Manrique has referred to her Mis caminos son terrestres XVII (My Paths Are Earthly XVII, 1985, fig. 16.2) as a “textile work,” or perhaps a “woven shape,” as opposed to a tapestry. The work shares two elements inherent in sculpture: it occupies real three-dimensional space (even though it is a rectangle, its volume requires a head-on view) and has tactile qualities (, 12). MUAC chief curator Cuauhtémoc Medina notes that critics have used the terms “soft sculpture,” “multi-dimensional textile,” and “sculpture in textile material” to refer to Bosch’s work (, 65). These definitions help us differentiate Palau’s artistic practice from that of other artists of the period.

Figure 16.2

Figure 16.2Mis caminos son terrestres XVII is made of henequen (a type of agave) and totomoxtle (a type of corn). Since the time of its making, deformations had occurred in the work’s textile support due to poor distribution of weight. Further, there was an accumulation of dust, decoloring of the dyed maize leaves, salts on some parts of the leaf surfaces, and overall rigidity and poor flexibility of the organic materials.

Preservation of this work required an understanding of its material authenticity based on the function to which the artist put the materials. The dyed maize leaves and their deployment in the textile is the most relevant component and holds the greatest significance. Therefore, intervention focused mainly on eliminating the deformations in the textile support and modifying its hanging system, since the original system was inconsistent and largely the cause of the deformation.

Following that, it was locally dry-cleaned to remove dirt and salt deposits. Controlled humidity (steaming) was also applied (within a chamber) to relax the deformations and make the leaves and the textile more flexible. Taking into account the meaning of the work, the fading coloration on the maize leaves was addressed. One ethical dilemma involved understanding and trying to reproduce Palau’s dyeing technique using new maize leaves. Because of her advanced age, Palau was unable to participate in an interview, so the students interviewed her assistant, Roberto Guillén Rodríguez. After conducting a test to identify the colorants used as dyes, the results revealed that the artist had used indigo and that the preparation techniques were very irregular, since the tones ranged from a darker black and some blue parts to others that were more reddish (, appendix 26). For that reason, it was decided not to attempt to replace, intensify, or retouch the original color. The researchers concluded that trying to match the colors seen in the piece would be highly complicated, and after assessing the alterations in the work, it was agreed that the present fading did not mar an appreciation of the work, and retaining the existing appearance better preserved its authenticity.

A sheet of Tyvek was used to wrap and store the work to prevent the accumulation of dust and to reduce exposure to light.

This research was important not only because of the significance of this specific artwork, but also because MUAC’s collection includes other Palau artworks. This case study established criteria for conservation of those as well as other textile works.

Case Study: Teresa Margolles

The work of Teresa Margolles (b. 1963) is noted for its rawness and its appropriation of materials associated with violent acts, mainly in northern Mexico. In the case of Encobijados (The Covered Ones, 2006, fig. 16.3), she arranged blankets that had been used to cover corpses on metal pipes. Medina writes of contemporary Mexican art, “Installation has been the privileged medium for expressing conceptual, activist, and experimental exploration since the 1970s. . . . Installation suddenly became common in galleries and museums, and demanded the type of contemplation that was appropriate for paintings and sculpture. . . . The work is altered to adapt to the museum enclosure” (, 13). In this sense it is significant that Margolles has been working in installation since the 1990s.

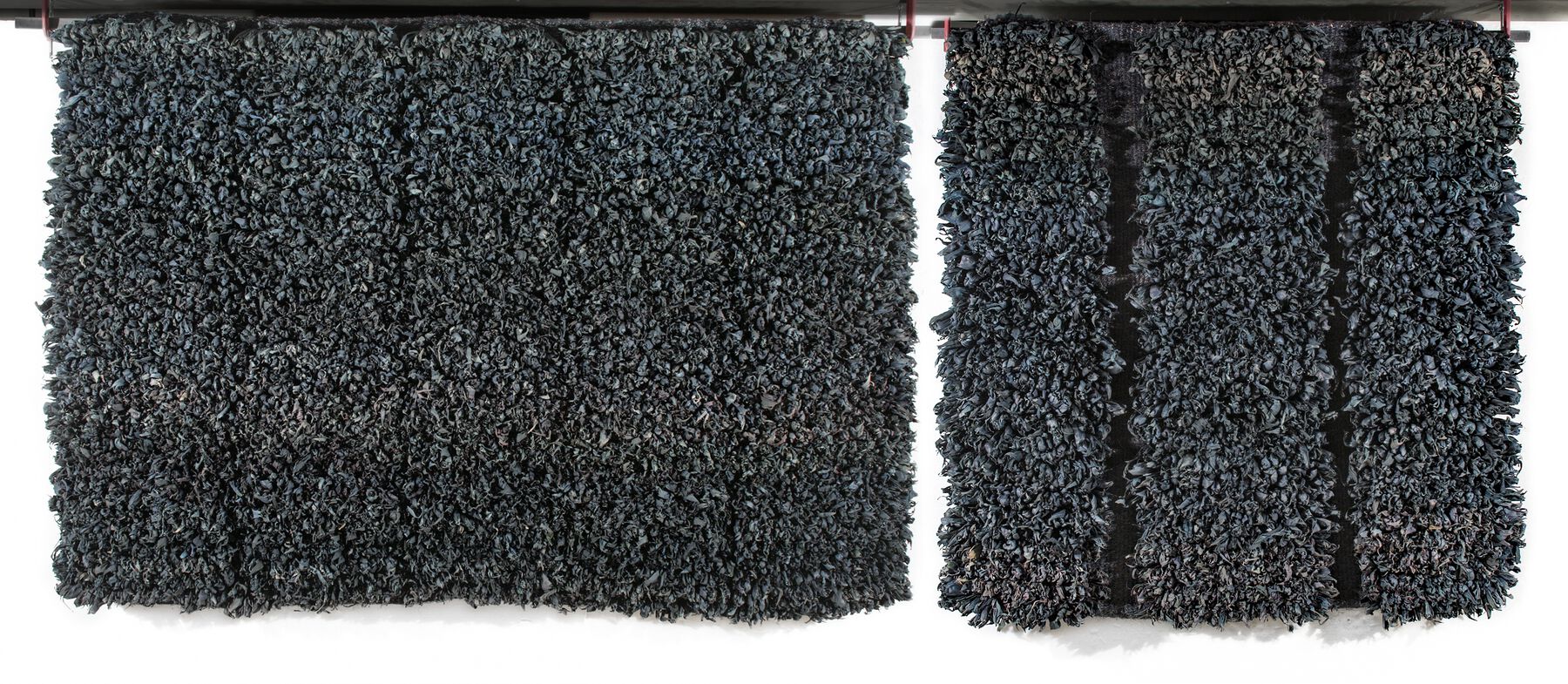

Figure 16.3

Figure 16.3The blankets bear organic bodily fluids, remains of plant matter (grass, dirt, dead insects), and adhesive tape because of their former use to wrap corpses (fig. 16.4). As they were never given any treatment to preserve the biological remains, the fluids have noticeably degraded. Some stiffened areas have also been noted, corresponding to the stains on the blankets, and some sections of tape have lost their adhesive and come loose. The last elements of the installation are metallic T pipes, which present no conservation issues.

It should be mentioned that only the diagnosis and proposal for stabilization have been conducted for this work; no interventions have yet been carried out. The main ethical dilemma regarding conservation of this piece is that its material authenticity is based on the function to which the artist puts the materials. Consequently, any intervention could irreversibly alter the meaning. Since the work’s acquisition in 2006, it has been in storage in an isolated drawer, under stable temperature and relative humidity (20ºC, 55 RH) in order to reduce organic degradation and oxidation processes. It is wrapped in Tyvek and thus not in contact with other artworks. The installation has been exhibited only once—in 2008, at MUAC’s inaugural show.

The diagnosis undertaken proposes treatments to disinfect the biological residue and document the stains under different specialized lights (UV, oblique, clear) as well as the locations of the pieces of adhesive tape in case it proves necessary to apply some type of bonding agent to keep them from coming loose (, 8). Lastly, the remains of grass, dirt, and insects should be analyzed to obtain more information on the place where the blankets were found. A biologist also provided important health and safety recommendations for handling of the work: as it contains bodily fluids, it is necessary to avoid direct contact with the skin (wear disposable globes, a face mask, eye protection, and a lab coat), and the artwork needs to stay in a stable environment (, 8).

It is relevant to continue researching and studying Margolles’s artworks, since MUAC holds in its collection other objects and installations by her and the group SEMEFO (active in the late 1980s and 1990s), of which she was a part.

Conclusion

Recent years have witnessed many productive collaborations in the Mexican conservation community involving partnerships between academia and museums, combining theory and practice in the care of contemporary art. Museums have served as spaces for practice and professional training for students, and for promotion of active dialogue among a range of specialists.

In the case studies above, the first conclusion is that it is essential to research the significance of organic and biological materials in artworks and to understand the intent of the artists, since these works must be understood as outcomes of a process, thus making them records of actions. The second conclusion is that the organic and biological materials used in contemporary art are extremely sensitive and delicate, so preventive conservation is key to preserving this type of work.

In the field of global contemporary art conservation, the Mexican community needs to study and publicize the context of Mexican art through case studies, new methodologies, and proposals for study and intervention. We should continue to disseminate internationally an understanding of the profession’s role and concepts in order to conserve our contemporary cultural heritage.

Bibliography

- Eder and Palau 1985

- Eder, Rita, and Marta Palau. 1985. La intuición y la técnica. Mexico City: Comité editorial del gobierno de Michoacán.

- Hernández, Yasky, and Learner 2017

- Hernández, Claudio, Caroll Yasky, and Tom Learner. 2017. “The Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art in Latin America: Recent Approaches in Chile and Mexico.” Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 32, no. 2 (Fall): https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/32_2/feature.html.

- Manrique 1978

- Manrique, Jorge Alberto. 1978. 30 escultoras en materiales textiles. Mexico City: Museo de Arte Moderno, INBA.

- Mata and Coronado 2018

- Mata, Lizeth, and Claudia Coronado. 2018. Diagnóstico de conservación y propuesta de estabilización de la obra Encobijados, de Teresa Margolles. Mexico City: Seminario Taller de Restauración de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo, ENCRyM-INAH.

- Medina 2006

- Medina, Cuauhtémoc. 2006. “Escultura suave, disidencia suave.” In Marta Palau. Nahualli, edited by Virginia Ruano. Mexico City: CONACULTA, Gobierno del estado de Michoacán, UNAM, Centro Cultural Tijuana, and BBVA Bancomer.

- Medina 2017

- Medina, Cuauhtémoc. 2017. Abuso mutuo: Ensayos e intervenciones sobre arte postmexicano (1992–2013). Mexico City: Editorial RM.

- Ortega Espinoza 2014

- Ortega Espinoza, Daniela. 2014. Informe de los trabajos de restauración de la obra “Mis Caminos son Terrestres XVII” de Marta Palau. Mexico City: Seminario Taller de Restauración de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo, ENCRyM-INAH.

- Rinehart and Ippolito 2014

- Rinehart, Richard, and Jon Ippolito. 2014. Re-Collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- van Saaze 2013

- van Saaze, Vivian. 2013. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artworks. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.